Net Worth

That’s what I liked about Yidel. He wasn’t playing pretend. He didn’t butter up to me. He didn’t look at me like I was some figure on an ivory tower

Nobody in shul was saying this aloud as I made my way past the sea of shtreimlach to the oiven uhn, but they were probably saying it quietly. Or at the very least, thinking it. Yumi Korn? Er shtekt arein ah Q-tip un schlept arois a hunderter, he sticks in a Q-tip and pulls out a hundred-dollar bill.

I’ve heard it too many times, and I guess I couldn’t exactly deny it. Who would’ve thunk, huh? Definitely not me, when Abish Meisels proposed that I buy off his fledgling urgent care business seven years ago. All I thought back then, as a 22-year-old schnook, was how reckless I was being, borrowing money from honest, well-meaning people — real people, adults — and gambling it on Meisels’s rosy promises.

I felt bad for Meisels now, and I consciously avoided his gaze as I passed the table where he sat with Berish Reichman, Azik Lefkowitz, and Shloima Chaim Eidlisz — some of the people who’d lent me all that startup money. I knew we were thinking the same thing: This could have been him walking up to the Rav at this annual Melaveh Malkah to humbly accept a silver megillah holder, a token of appreciation for sponsoring the shul’s gas and electricity for the next twelve months. I could only imagine how many times a day he regretted the sale, considering how exceptionally his rosy promises were realized.

But he couldn’t have thunk that either, right? Nobody could have thunk up Covid, and all those thousands and thousands of noses the Q-tips of my tiny, no-name urgent care would be swabbing overnight.

Sometimes I felt bad for the physicians I employed. They were decades older than I was. They’d sweated their way through medical school. And for all that, with their professional rates, what did they earn? A salary. A respectable salary, okay — I’m a generous boss — but they earned exactly what I paid them for showing up at the facility every night and seeing my patients, nothing more. While I….

I earned a hundred bucks on every Q-tip they touched.

And there were many. Q-tips, that is. In the six branches of my tiny, no-name urgent care that wasn’t so tiny or so no-name anymore.

The megillah holder was beautiful, and I told the Rav so, at the same time that my mind whizzed through the same math that was surely whizzing through the minds of everyone else in shul. How much did this silver piece cost compared to the building’s cost of utilities for one month? A lot less, I knew, and I hoped they did, too.

“Apuhr verter, would you say a few words?” the Rav murmured, parting his moustache earnestly.

My toes curled in my Tom Fords (Zissi’s pick, not mine). It always felt funny when the Rav showed me respect. And seriously, did I have anything to say? I’d been approached by Shimmy Stengel, the shul’s gabbai, about the utility bills — “Bli ayin hora, the oilam nearly doubled over the past few years, we’ve got the air conditioning blasting five months a year, and you know how much heating costs?” — and of course I’d agreed to cover them. Wasn’t that why Hashem gave me money? To do good things? To boost Torah and tefillah, make avodas Hashem comfortable for my fellow mispallelim?

Okay, that was probably something I could say.

“Nu nu,” I muttered.

I turned around to face my fellow mispallelim. Something fluttered in my stomach — the oddness and giddiness of little me addressing all those real-world yungeleit — but it passed swiftly as I gave a modest nod and raised my hand as though in helplessness. “Shkoyach, shkoyach,” I started humbly. “It’s my greatest honor. And really, we all know, this isn’t really me. I’m only a shaliach from the Eibeshter, and it’s a kavod to assist all the choshuve people of our kehillah, all the talmidei chachamim who spend so many hours davening and learning in our beis medrash.”

There was a flash of blue, and I vaguely processed that the photographer was capturing this moment. How did I look, standing at the podium? Well, I’d find out when the Frimurgen came out on Monday. I’d also see it in the shul’s photo archives, a growing collection on the members’ shared Drive – Azik Lefkowitz’s baby.

My fingers tingled from the weirdness, but I forced myself to focus on what I was saying. I took a moment to talk about the Europe nesiyah we were planning — a major siyum celebration — because I knew the Rav would appreciate my stoking the momentum and padding the pride we all took in our beloved beis medrash, and then I finished with a heartfelt brachah for our Rav, tipped my head modestly, and headed back to my seat.

“A sheinem shtickel,” Yidel Weinfeld assessed when I reclaimed my spot next to him. He held up the megillah holder, analyzing it from every angle, like it was an esrog or something.

That’s what I liked about Yidel. He wasn’t playing pretend. He didn’t butter up to me. He didn’t look at me like I was some figure on an ivory tower.

Because I wasn’t. I was the same old friend I’d always been. We’d played galachim in front of the shul building as eight-year-olds, we’d been chavrusas every Shabbos afternoon since we were twelve. The title gvir changed nothing for us, and I loved that there was this one person in my life who still behaved completely natural around me, who didn’t allow a gap the size of my bloated bank accounts to stand between us.

“Hey, Korn!” Zalmen Slomuic called from across the table. “Beautiful speech. And I saw the ad in Der Moment — the Ohr HaLimud campaign — pshee aaah….”

My palms perspired into the sheinem shtickel in front of me, and I did my best to control the heat that rose to my cheeks. Slomuic was referring to the Kesser Malchus award I was being presented by my Yanky’s cheder. But there was nothing innocent in his comment. He was trying to win favor in my eyes, so that I would come around and catch the 75k he was throwing on me. Like so many of my “friends,” he was sure I would take his money and triple it for him within a year.

Because there was another thing I knew my fellow mispallelim may be saying about me. Yumi Korn? Er hut mehr mazel vi seichel, he’s got more luck than brains.

That was a less flattering shushka, but did I have a right to deny it? The truth was that I did not come into my money by anything other than a wide stroke of luck.

And that luck — everyone angled for a share of it. They hoped that by attaching themselves to my orbit, they’d gain some of it, too.

Exhaustion hit me suddenly. I wanted this, I enjoyed making a difference in people’s lives, but moments like these with everyone looking and whispering felt like swallowing too much ice cream.

This Melaveh Malkah was pretty much over, now that the appreciations had duly been delivered. “I think I’m going to bentsh now and leave,” I told Yidel.

“You should lacquer the megillah holder,” he responded.

I should. Or our cleaning help could polish it twice a day, for all it mattered.

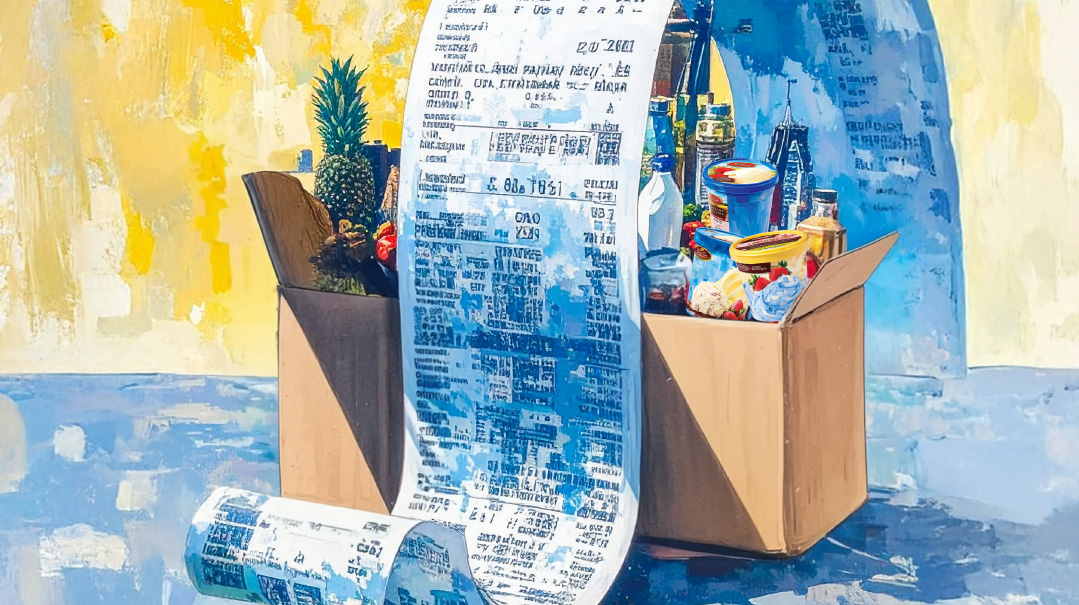

There was a grocery box blocking the entrance to my house when I arrived home. Right, Zissi had mentioned that Main Course started doing deliveries on Motzaei Shabbos in the winter. She must have placed a phone order after the zeman.

“Gut voch!” I called out as I planted the box on the kitchen floor. “Hey, I’m coming from a melavah d’malka, and guess what I just realized? I’m hungry. I ate a kezayis to be yotzei, that’s all.” I ripped the tape off the box and started rummaging inside. “Bought anything good?”

“There should be ice cream in there,” Zissi said. Ice cream was a treat our family embraced on Motzaei Shabbos even in frigid weather. I found the container at the bottom of the carton.

“What’s this?” Zissi asked. “You got a megillah holder?”

“What’s this?” I echoed voicelessly.

This was a receipt I’d found nestled between a bag of sourdough pretzels and a bottle of Tuscanini olive oil.

Total balance: $12,304.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1081)

Oops! We could not locate your form.