Au Revoir, Rav Yisrael

| June 24, 2025What brought Rav Yisrael Salanter to secularized Paris in his last years?

Title: Au Revoir, Rav Yisrael!

Location: Paris, France

Document: HaMagid

Time: May 1880

This esteemed person [Dr. Judah Sternheim], contemplating the Jews of Poland and Russia who had lived there [in Paris after their immigration] many years without guide or shepherd, was troubled over his brethren lest they become lost in a pathless wasteland. He decided to act on behalf of G-d and His faith, and girded his strength to arouse the great eagle from its nest — namely, the great gaon and sublime tzaddik, our teacher Rav Yisrael Salanter, may he long live — to come here [to Paris] so that he may oversee the activities of that congregation, and that this stumbling block be under his control.

—HaMagid, 1882

After 17 years of prodigious activity in Vilna and Kovno spreading the ideals of mussar, Rav Yisrael Salanter left Eastern Europe in 1857, returning only for sporadic visits. For the next 26 years of his life, the great founder of the Mussar movement, and one of the greatest tzaddikim and geonim in the whole Russian Empire, resided in various cities across Germany — Halberstadt, Konigsberg, Memel, Berlin, Hamburg — and even spent a curious two-year stint in Paris, France.

What was behind his sudden departure? Why did he remain in Western Europe until his passing? And most importantly, what did he set out to accomplish during his long sojourn away from familiar surroundings?

He left for Germany to seek medical care for his worsening health issues. After he’d been there for several months, his observations on the spiritual state of German Jewry made him decide to remain. While Eastern Europe was then beginning its own confrontation with modernity and secularization, Germany and other Western European Jewish communities were already decades into the experience.

Rav Yisrael had a keen perception of the societal trends and challenges facing German Jewry, and he embraced the responsibility to act on behalf of his people. He decided that his physical presence in Germany would boost his attempts to help individuals and communities strengthen their religious observance.

In the winter of 1880, he arrived in Paris, already 70 and in failing health. What could possibly have brought Rav Yisrael Salanter to Paris at this juncture of his storied career?

As Jews sought to escape the brutal and anti-Semitic rule of the Romanov czars, as well as the grinding poverty of the Pale of Settlement, there was a slow and steady migration to Western Europe and the United States during the 19th century. By 1880, there was already a substantial community of Polish-Russian Jewish emigres residing in Paris. And because it was far from the cohesive communal infrastructure of Eastern Europe, this diaspora community was rapidly secularizing.

Dr. Judah Sternheim, who had been Rav Yisrael’s host in Berlin and had remained close with him, moved to Paris. There, Dr. Sternheim devoted himself to the affairs of the Jewish community, even establishing a religious educational framework for immigrant families. He invited Rav Yisrael Salanter to serve as the rabbi of this community, confident that someone of his stature would have a positive impact on the local inhabitants. Despite his age and frail state, Rav Yisrael acquiesced, and arrived in Paris for a two-year stint.

From the outset, Rav Yisrael viewed his role as temporary, filling the role until he himself could recruit a suitable candidate to take over permanently. He initially tried to convince his protege Rav Hillel Milikovski, known as Rav Hillel Salanter after Rav Yisrael successfully secured him the appointment as rabbi of his own former city — in which capacity Rav Hillel served for 18 years. Rav Yisrael even sent his talmid a personal letter requesting he assume the position in Paris, along with a formal ksav rabbanus (letter of appointment), and even funds for travel expenses. Rav Hillel demurred, however, not wishing to move to a foreign land.

During his stay, Rav Yisrael tried to unify the fractured immigrant community. Among those who flocked to him for his wisdom and guidance were a cadre of young maskilim who had sought acceptance from the many European academics who had made Paris their home.

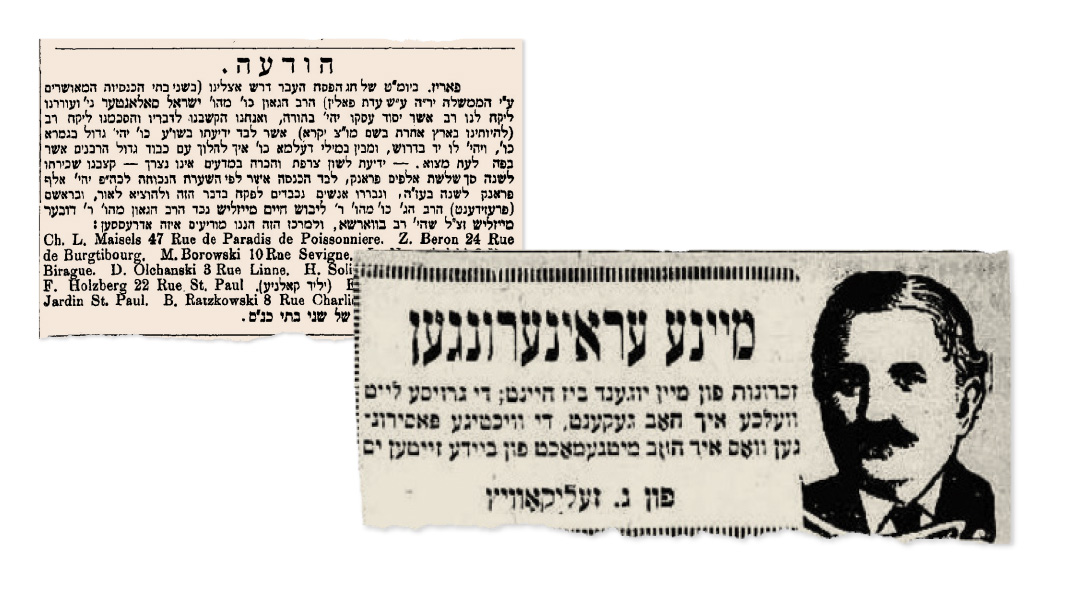

One such student was Getzl Zelikovitsh (1863–1926), who visited Rav Yisrael regularly while studying in Paris in 1880. In his memoirs, serialized in the Yidishes Tageblatt in 1919–1920 under the title Meyne Erinerungen, he devotes several pages to the great Mussarite — including several treasures that we believe have never been published in English before.

Zelikovitsh shares how Rav Yisrael made it clear from the outset what type of interactions he was open to from the curious students: “If you want to know what kind of hat the Rambam wore or the color of Rashi’s trousers, ask your Derenbourg, Darmesteter, or Renan [names of academics popular in Jewish circles]. If you truly want to understand a commentary by Rashi or a ruling of the Rambam, don’t go to them — come to me.”

Rav Yisrael understood that if he could interact with some of these popular Jewish academics, he would gain the trust of the young minds he wished to bring back to their roots. His outreach wasn’t always conducted by traditional means.

When renowned Jewish scholar Joseph Derenbourg expressed interest in meeting him, Rav Yisrael insisted that it was more appropriate for him to visit Derenbourg’s home. A carriage was dispatched, but upon arriving at 27 Rue de Dunkerque, Rav Yisrael stopped short.

“Getzl,” he said, “we’re leaving immediately. I will not enter a Jewish home without a mezuzah.”

They turned around and departed without fanfare.

Derenbourg’s response, as Getzl later recalled, was striking: “It’s truly a pity — but from his point of view, he’s entirely right.”

Rav Yisrael’s uncompromising integrity was deeply respected. The mutual respect between the traditional Lithuanian gaon and the assimilated academic symbolized a fleeting moment of reverence: Even in secular Paris, Torah conviction still commanded awe.

Rav Yisrael Salanter’s reverence for Lashon Hakodesh extended far beyond grammar. When handed Ḳehal Refa’im, a collection of modern Hebrew poetry by maskil Moshe Leib Lilienblum, Rav Yisrael sighed heavily.

With pain, he lamented what had become of the holy tongue: “What a heap of rags has been printed in the language of our prophets!’

“Understand me,” Rav Yisrael said gravely, “writing in the sacred tongue is a very serious matter in my eyes. What matters is what one writes. You certainly know the verse, ‘Your palate is like exquisite wine’ [Shir Hashirim 7:10]. Good wine is inseparable, for us Jews, from the sacred. The ceremonies of Kiddush and Havdalah are celebrated with wine, also used in many other rites. That is why wine is a noble thing among us. And yet if an idolater touches it, it becomes unfit for consumption.

“It is the same with speaking and writing the sacred language. Obviously, it is a holy language for us, but when it is used for trivialities, it becomes unfit. Your palate — the noble and precious Hebrew — shares the same fate as good wine.”

His fiery derashos in the local shuls drew crowds, and those in the audience were enraptured by his pathos, authenticity and charisma. That itself was at least a partial achievement of his goals. The community had been wracked by controversy prior to his arrival, and he managed to quell the dispute (although it returned after his departure). A maggid named Rav Yehuda Lubetzky had a following among Russian emigres, and they wanted him appointed rabbi of the entire community. Rav Yisrael convinced him and his faction that his position as maggid could be formalized, and he’d serve as the spiritual guide to his followers in their own shtibel. But regarding the rabbinate position, it was imperative that it be someone accepted by all.

After two years, Rav Yisrael was finally able to convince his dear friend Rav Yehoshua Heshel Levin to fill the position, albeit provisionally. One of the most fascinating characters of 19th-century Lithuanian Jewry, Rav Yehoshua Heshel in his second marriage married the daughter of Rav Eliyahu Zalman, who in turn was the son of Rav Itzele of Volozhin. He soon became embroiled in a dispute with his uncle, the Netziv of Volozhin, over his serving in a formal position in the Volozhin yeshivah.

Ultimately it was decided against Rav Yehoshua Heshel, and he relocated to Vilna. In addition to serving as a rabbi for short stints in Warsaw and a couple of other towns, Rav Yehoshua Heshel was quite active on the public scene, often together with Rav Yisrael Salanter. He was a tremendous talmid chacham, and published several of his own seforim, in addition to editing unpublished manuscripts and arranging their publication. For many years he attempted to launch a Torah journal that would unite rabbis across Russia through Torah essays. His most famous literary endeavor was the publication of his Aliyos Eliyahu, the first and for many years the only authoritative biography of the Vilna Gaon, which proved to be immensely popular and went through several printings.

Old age and ill health brought Rav Yehoshua Heshel to Paris in the first place. Acceding to Rav Yisrael’s entreaties, he agreed to remain as rabbi there for a couple of years until his health improved enough that he could fulfill his lifelong dream of moving to Eretz Yisrael. Frustrated that he couldn’t find a permanent rabbi for the Russian Jews of Paris, Rav Yisrael secured a promise from Rav Yehoshua Heshel that he wouldn’t depart for the Holy Land until he had found a suitable successor.

Unfortunately, it was not to be. Not long afterward, Rav Yehoshua Heshel succumbed to his illness and was buried in Paris. Recently, his remains were reburied on Har Hazeisim.

This took place after Rav Yisrael’s departure from the City of Lights. In several letters from that time period, Rav Yisrael expressed deep satisfaction with his Paris journey. In ill health, he had been encumbered by this challenging situation among the immigrants, and had not quite successfully solved the issues, despite having dedicated a full two years to doing so. Rav Yisrael Salanter returned to Konigsberg, where he passed away about a year later. —

Not my Cup of Tea

The story is told that shortly after arriving in the bustling French metropolis, Rav Yisrael Salanter sat down for a cup of tea in a café on a wide thoroughfare. When it came time to pay, Rav Yisrael expressed surprise at the expensive price for a simple glass of tea. The maître d’ explained that the bill didn’t just include the tea.

“Look around,” he said. “The ambience of this tastefully decorated café, the decor, music in the background, the view of central Paris… that’s what you’re paying for. And that certainly justifies the steep price.”

The quintessential baal mussar immediately applied the lesson to spiritual growth. “When we wake up in the morning, Hashem doesn’t just provide us with health, food, sustenance. He created an entire beautiful world as a backdrop, with all of its many amenities for us to enjoy. Hashem created it all for us to enjoy, and we need to pay any price in our own avodah in order to pay Hashem back for His endless gifts bestowed on us.”

(Heard from Rabbi Mordechai Stern)

Defender of Tradition

One of Joseph Derenbourg’s most influential works was Essai sur l’histoire et la géographie de la Palestine d’après les Thalmuds et les autres sources rabbiniques (“Essay on the History and Geography of Palestine according to the Talmud and other Rabbinic Sources”). This book was a groundbreaking effort to reconstruct the history of Eretz Yisrael during the pivotal period of the Second Beis Hamikdash, covering the era from Cyrus the Great to the Roman emperor Hadrian.

What made the work so revolutionary was its methodology. In an academic climate often skeptical of the historical value of rabbinic literature, Derenbourg took the opposite approach. He placed the teachings of Chazal, found in the Mishnah, Gemara, and Midrash, at the very center of his historical investigation, treating them with the respect due to primary source material. He meticulously combed through these texts to illuminate the major events, personalities, and social movements of the time, including the Anshei Knesses Hagedolah, the disputes between the Pharisees and Sadducees, and the lives of Tannaim such as Rabi Akiva and Rabi Yishmael.

The book was immediately recognized as a major contribution to the field and was heavily utilized by later scholars. The work’s importance to the world of Jewish learning was further cemented when it was translated into Hebrew by M. Brann under the title Masa Eretz Yisrael. This Hebrew edition was enhanced with additional scholarly notes by the renowned bibliographer and historian Avraham Harkavy of St. Petersburg. By using the tools of modern historiography to affirm the world described in the Talmud, Derenbourg provided a powerful and enduring model for how academic methods could be employed to deepen, rather than undermine, an appreciation for traditional Jewish sources.

The research and writings of Professor Imanuel Etkes were utilized in the preparation of this column.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1067)

Oops! We could not locate your form.