On the Winning Team

While my journey had been inward-focused, I now viscerally felt what the support of others could do

As told to Rivka Streicher by Yehuda Weiss

While my parents were well-intentioned, their hardline approach in our insular community didn’t work for me. I was restless, confused, maybe depressed, yet all I knew was that I wanted out. I began engaging in self-destructive behaviors, felt like a failure, and fell and fell. But here's the thing about hitting rock bottom. There’s no way out but up

I

wonder, sometimes, if I was ever a carefree child. From early on, cheder was not my happy place. The rules, keeping my finger on the place in the siddur, Chumash, Mishnayos — and the, often, corporal consequences if we didn’t do, listen, follow, follow, follow.

For a thinking, inquisitive child it was hard. I felt like a sheep — always having to shuffle, trot, and bleat the same way as the others, and if not, I was at the rebbi’s mercy.

If only home could’ve been my safety zone, the place I could retreat to lick my wounds from cheder. But home was just another place to hide.

“You don’t know what my rebbi did to me today…” I’d try to say to my father.

He’d turn on me. “Why did he do that? What did you do to deserve it?”

I’d mumble something.

“You did that? Well, we also need to discipline you.”

I learned quickly not to trust anyone, to keep my pain and shame to myself, to resist sharing because I couldn’t expect compassion.

To be sure, my parents were good, well-intentioned people, but at the time, to them, good parenting meant reinforcing expectations and doing whatever it took to keep us on the straight and narrow.

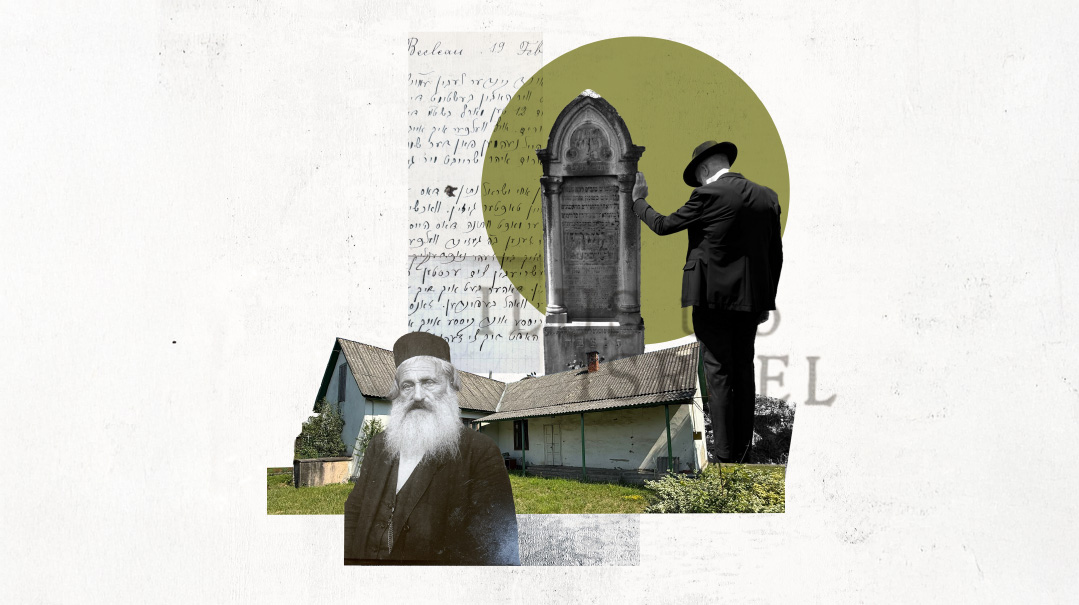

Were they worse than other parents, than my friends’ parents? Probably not. Like most people in our insular, chassidic community, they were young when they started a family, and were treading the path they knew without really thinking about why they were doing it. When they encountered negative behavior, they’d treat the symptom by reprimanding or punishing, without stopping to consider the root cause.

And then came a sensitive second child like me. Their hard-line approach just didn’t work. I didn’t feel that my parents were in my corner or that they had my back unconditionally. Sometimes, I felt, What am I to you? A trophy? To look good and right in my place in the family’s perfect picture?

I was around 11 when I began struggling with anxiety and depression. I didn’t know why I was feeling full of nervous energy at times, and like I didn’t want to get out of bed at others. Lazy and unmotivated were the messages I heard about myself.

When I’d try telling my mother that I didn’t have energy, or felt sad, she’d downplay my feelings and fears, pushing them back under the rug where we could walk over them and pretend they didn’t exist. “If you only try harder, you’ll be fine,” was what she told me over and over.

The world of mental health, especially children’s mental health, was hopelessly simplistic and misunderstood at that time in our community. If you’re crazy, you belong in a mental institution. If you’re not that crazy, just get over yourself.

So I tried, but I’d sometimes experience debilitating panic. I often couldn’t sleep, and my emotional angst kept me up at night. The anxiety kept me from doing things. I felt different, like I just couldn’t fit into a world where fitting in was almost the only thing you had to do.

As I approached teenagerhood, these feelings led me to act out in rebellious and self-sabotaging ways. It started with tiny things, like refusing to get a haircut at the same prescribed time as the other boys. Pushback from yeshivah and from home came fast; the more I pushed, the more they’d come back at me. I felt that my home, yeshivah, and community were one big prison. And my parents were the prison guards.

Teenagers have intense feelings where everything is a huge deal and can look like the end of the world. The depression intensified and I had little will to live — I couldn’t see a point to it all. Most days, I did the bare minimum just to get through, to survive. That my parents didn’t know how to deal with or accommodate me just exacerbated things.

I chafed at going to yeshivah every day, and abiding by the same rules, same schedule. It felt meaningless. I felt meaningless. I acted out in bigger ways, and at 15, got myself kicked out of yeshivah in our community.

I was sent to a less-intense yeshivah in Monsey, where I learned that the world is bigger than my own chassidus, that there are other types of Jews.

I still couldn’t find my place and continued heading downhill. By then, I was used to fighting with authority, as if my problems were external and if I would come head-to-head with everyone outside and on top of me, I could feel better.

By 17, I was out of the Monsey yeshivah and landed in a much-more-lenient-than-my-parents-would’ve-liked yeshivah in Lakewood.

Still, they didn’t ask, “What’s going on for you, Yehuda, that you keep acting out?” They didn’t take my mental health challenges seriously. If the new place was more open, it was still a yeshivah. So long as I was still pushing through the system.

“Y

ou’ll have to speak English better in order to interact with the other boys here,” the Rosh from the Lakewood yeshivah told me at our interview.

I could barely speak English. In cheder we’d learned the alphabet, how to write our names, and little else. We’d throw peaches at the English teachers who came in a couple times a week for the last 45 minutes of the day. They’d resort to telling stories so we wouldn’t bombard them with fruit.

I did have a basic understanding of English, so the Rosh would give me the weekly Rav Avigdor Miller pamphlets in both Yiddish and English and by comparing them I learned to read and write.

In this yeshivah, boys were encouraged to explore their talents and even to find a job for a few hours a day. The Rosh found out that I have a talent for art and allowed me the use of a room as a studio. I painted a lot in those days, experimenting with different media, creating and expressing what I felt in abstractions, color, and shadows. It was cathartic, but at that point, there was so much dissonance within — the supposedly good people not bothering to understand me, the deep pain of being different, of not being good enough, and all that underlying anxiety, augmented by periods of depressive darkness. I was struggling too much for art, or any outlet, to help.

But my artwork was displayed in the yeshivah, and that’s how someone from the Lakewood community commissioned a painting from me. He wanted four people dancing the kezatzka in a certain textured technique. He paid me a few hundred bucks, my first time earning my own money, and I went wild on a heart’s whim.

For so long, I’d wanted out. I was surviving at yeshivah, but when I’d come home for Yom Tov, as I’d inevitably have to, my parents couldn’t handle how I looked — still “black and white” but with things like a hoodie and tighter pants. The neighbors would stare, people would tsk. I’d feel my parents’ anguish and embarrassment, that they were trying to hide me, like there was something deeply wrong with me.

That hurt so much. Now that I had some money, could it buy me a ticket out?

I gave the cash to a friend and used his debit card to buy myself a ticket out of New York. I chose Los Angeles; it was far enough, and hey, wasn’t it on the coast?

The next morning, I hightailed out of yeshivah, and as luck would have it, I met the Rosh on the staircase.

“Where are you going so early?”

“Job interview,” I mumbled.

He didn’t question that, saying instead, “Best of luck, Yehuda,” in his heartfelt way. That almost broke me.

“Where’s your passport?” they asked me at the airport.

I showed them my local ID card; I hadn’t thought I needed a passport to fly within America. They laughed me off. I riffled in my pocket and came out with my social security card.

They called Washington, and after asking me a few questions, which matched the information on record, waved me through.

I was off. Elated and exhausted, a boy who didn’t know who he was, but just for now, flying high.

The plane landed at dusk and too soon I was out of the airport. I still had some cash and thought I’d get a hotel room. I tried a couple of places, but they wouldn’t let me check in without a passport or credit card.

Utterly drained and exhausted, I sat down a park bench. My phone’s battery, too, was gone. The weather was balmy and I lay my head down. Feelings roiled inside, my own inner sky full of clouds; anger, rage, sadness, apathy. In the grip of so many emotions, I couldn’t spare a thought to consider how dangerous it was to sleep on a park bench for the night. Drowning in my own sky, I succumbed to sleep.

Come morning, I walked away from the bench and saw another person claiming it for himself and his tattered bags. Clearly a homeless guy. Was that who I was, too?

I worked up the courage to walk into a convenience store and ask for a charger. I charged my phone and with a sinking heart, called my father.

“I’m in Los Angeles,” I said.

He didn’t ask why or what. Woodenly he said, “I’m booking you a flight back to New Jersey, you’ll go back to yeshivah.”

I took that flight and went back.

We didn’t talk about what happened, not then, not when I came home. Not until four years later.

“R

unning to L.A.? You must be feeling terrible inside that you had to do that….” The Rosh shook his head compassionately. “I understand that, Yehuda.”

His voice was kind and sad, but could he really understand? I was the biggest loser. I couldn’t even do running away right.

“For the next few days, take it easy — you don’t have to participate in seder. We’ll tell the others you’re not feeling well. After all, what you went through really is traumatic. All I’m asking is that you think about what you want to do with your life.”

I knew what this meant. They weren’t kicking me out — that wasn’t their way — but it was becoming increasingly clear that I was too big a case for them to handle.

I sat, holed up in my room, trying to think about what I wanted to do with my life.

It doesn’t matter. My life doesn’t matter anymore. It’s so messed up, I don’t know where I can go from here.

What if you could help other people, save other lives? A little voice inside nudged. Then, your own life would matter by default.

Fair logic.

“I want to be a cardiologist,” I told the Rosh, when we spoke again. Talk about saving lives.

“Okay. And what do you need to do that?”

“Go to college?”

“And can you get in? Do you have your high school diploma?”

“Nuh-uh.”

“So work on your GED right here in yeshivah.”

I have to hand it to him, he remained positive and gung-ho. He wasn’t humoring me, he really wanted to accommodate me. But I wasn’t up to yeshivah anymore.

The Rosh called my parents and told them, “Yehuda’s coming home to do his GED and go to college.”

That was it. I’d officially dropped out of yeshivah.

At home, my parents’ disappointment hung in the house like another set of curtains. Behind it was anger, disgust, shame. Dazed and disturbed, I slept long hours.

For several months, I didn’t do anything to get on with obtaining my GED or applying to college. Day after day, I was a shadow at the table or on the couch or out with other dropouts in their dark corners.

My parents all but tolerated my presence at home. They were at a loss with me, and the sense I got from them was that I was beyond help, when one day, my aunt showed up in my life.

She sat herself in the couch in the living room, and she offered me a straw to grasp onto.

This was my accomplished aunt, the one person in the family who’d gotten a college degree, the indefatigable woman who’d established her own ABA clinic, saying to me, “Do you want a job at my clinic? I think you have what it takes.”

She thrust some books at me. “Read this stuff, make sure you understand it. At the end of the week call this guy” — she gave me a phone number for a doctor who was a partner in the clinic — “and he’ll test you on the material. If you know it, you can come work at the clinic.”

I’d never heard of ABA therapy and I’d never worked with special-needs children. But her trust in me, that was something.

She gave me the trust my parents didn’t have in me. That I’d all but lost in myself.

I started reading and was floored at what I discovered. Science, psychology, a whole new world. I read about how the mind works, about mental health, about depression and anxiety.

While the going was hard — working through those textbooks I had to keep looking up words and terminology — what I was discovering was more than knowledge, it was essentially myself. What I was feeling; that there were whole books, an entire field, devoted to the study of mental health; that there could be intervention, even healing.

Deep down, maybe I’d known that, but here it was, black on white.

Before long, I started working at the clinic with the kids. I saw how ABA therapy helped them, reinforcing positive and reducing negative behaviors. We worked on skills development together. It was hard but rewarding work. All the while, I kept up my studies, learning other psychological approaches. My reading and learning became an obsession that had nothing to do with working at the clinic. I learnt how to use Google Scholar, read journal articles, and understand experiments and studies. Although I did not have access to worldly knowledge, yeshivah had taught me how to learn, how to ask questions, how to apply myself to an issue and understand it in depth.

I pursued the world of psychology ardently, desperately. If I could only understand mental health enough, I thought, I could find a cure for myself, I could feel better. The work wasn’t motivating me as much as the rush to find out more.

The truth is, I wasn’t ready then to really put in the work to heal. Paradoxically, finding out more about mental health had become a distraction from facing myself.

For six months I worked with the kids at the clinic in the daytime and read voraciously at night, giving myself to both the work and the learning. Working with the children felt good, like I was doing something meaningful, but with that relentless learning alongside it, I was also careening toward a crash.

Beneath that overworking person was a boy still struggling with depression and anxiety, who was using the workload and the learning as a coping mechanism.

I’d started taking medication for depression, but I found that six hours into the day, the medication wore off. Nighttime, I always felt terrible. Eventually, despite doing actual good work at the clinic, the facade came down. My crazy lifestyle caught up with me and I couldn’t keep things up anymore. I quit the job.

Those were dark days. I was engaging in self-destructive behaviors, feeling like a failure, falling, falling. Until there was nowhere to fall; I’d reached rock bottom.

“S

end him to rehab, his mental health issues are beyond you. It’s dangerous, a matter of life and death.”

That’s what my parents were told by askanim in the community.

I was sent to rehab in Florida — the first steps on the long road to healing.

In the months I was there, I learned to confront myself. There was nowhere to escape to, nowhere to hide. Everything came to the fore, including my issues with religion and observance — being misunderstood by the “good, holy” adults in my life.

Rehab was intense, the work taking me down and deep, finding the Yehuda that had long been lost, owning up to my life, taking responsibility. I left the program, feeling vastly better but vulnerable as a butterfly.

I remember my first phone call to my mother after rehab (where I had little access to my phone).

“Ma,” I said. “It’s Yehuda….”

I told her of my journey, that I was in a much better place as a person, but not religiously.

On the other side of the line, she cried and cried.

“I’m still your son…” I said, and it came out with a question mark.

“You’re always my son…” she sobbed.

“So can I come home?”

She started hemming and hawing. “I’m not sure. Let me check with Tatty….”

Tatty, though, was disassociated from what was going on with me. He couldn’t be in contact with me directly. My being was too painful for him and he chose to check out.

He did, however, try to help indirectly. He got a religious chaplain to keep an eye on me in the halfway house that was my next step. When I got out of there, he got people from the community in Miami to look in on me. They did, bringing me food and inviting me for Shabbos meals. Their overtures meant a lot at a time where I was feeling isolated, having just left the safety of constant supervision at rehab and then group living at the house.

I was trying to integrate back into society — renting my own place, obtaining and holding down a job for a few months. Things were on the rise when my boss suddenly upped and left to Europe indefinitely, due to health reasons.

The guy who took over the company told me, “I don’t see the relevance of your job anymore, you can go home.”

That threw me for a loop when I wasn’t really standing firm yet. I had little money and no schedule, and a terrible low followed that tentative rise. I woke up late, and mostly stayed in the apartment, going out very sporadically just to buy food. I started self-sabotaging behaviors again, which — painfully, hopelessly — threatened my whole recovery.

In my isolation and brokenness, I received a call from my parents.

“We’re coming to Miami for Shabbos.”

What?!

“To be with you,” was their response to the question I couldn’t even ask.

A miracle brought them over. Stars in my dark sky.

That Shabbos we ate together and spoke a lot. I felt like something integral had changed. For the first time, I didn’t feel their judgement or despair. There was a different quality about them.

Still, doubts and questions wormed their way in, but I tuned them out, instead just leaning into the feeling of having them there. They’d gotten over themselves and come, just for me. That whole Shabbos was a miracle.

It turned out that a rav from our community whom my father used to learn with was in Miami that Shabbos.

“Would you have a conversation with him?” My father asked.

“Whatever. Why not? That’s if he’s okay with me telling him everything that’s wrong with the system.”

I went in there and started yelling about, “the insularity of the community, the lack of awareness of mental health, the lack of resources….”

He nodded sadly, taking the wind out of my sails.

Gently and kindly, he asked me about my experiences. He heard me out and then asked for my ideas regarding awareness and resources for the community.

I’d gone in guns blazing, but we ended up having a hopeful conversation.

“You know,” he said, “where you’ve been, what you’ve experienced, you could really help people from the community.”

That planted a seed.

By the end of Shabbos, I was feeling much better, but I was still wary about where this was going. My parents, though, were more serious than I’d realized about repairing our relationship.

“We want you to come home and we really have to change some things. We want to know how we can better understand you…” my mother said. For a moment I stiffened, thinking that they wanted me to agree to changes, but I realized, with wonder, that they meant changes within themselves.

W

ithin a week of my parents’ visit, I cleared my stuff out of the Miami rental and got on a flight.

It had been years of being away — from the community, the culture, the dynamics of home. In the last couple of years, I’d been out there in the gritty world. There had been almost no one with whom I spoke Yiddish. Those first few days home were full of flashbacks, memories surfacing and holding me in their grip.

There were also the masses in their black and white and conformity. I knew that the people on the streets couldn’t be in my radar, and I set my sights on family. That was my priority, the relationships I wanted to relearn, from my new place, now that my parents, too, were in a different place.

“We hit rock bottom,” my mother said, her language about their journey mirroring my own. “We lost you completely. You were far away and we had nothing to do with you. And that’s when we realized that maybe we’d gone about it wrong.”

The hard-line approach, shunning me, trying to put me in my place — it had all pushed me in one direction.

“We just surrendered. We didn’t know what to do. And we reached out for help.”

From my own work, I knew that that’s all you need for a start. When you’re humble enough to try something other than what you’ve always thought, because part of the gehinnom you were experiencing may have been of your own making.

Then came perspective, curiosity, openness. What I found was, instead of resistance, tentative acceptance. They weren’t so afraid anymore, they didn’t put the onus on themselves to “fix” me.

For my mother it was easier. Instead of saying, “Why are you doing this?” she changed it to, “What’s bothering you?”

It was like a switch had gone off, and she became a light.

My father took more time. He was much more bothered by things like me looking different. He needed my mother’s support. Her light. And she was a beacon. She started her own chapter of a support group for parents of struggling children right in our community. She led from her heart and from her own experiences.

“But the Eibeshter… does the Eibeshter let?” my father kept asking.

“The Eibeshter planned this,” she’d tell him. “We can only look at ourselves. As parents, we’re here to support and to help our children. The outcomes, what they look like and what they do. Today, it’s not on us.”

She had a lot of perspective; she’d come to the essence of what it was to be a parent. And she was patient with my father until he, too, came on board.

While I’d ostensibly relapsed after rehab, now at home, not needing to be concerned with food-and-shelter-level-survival, and finding a strong sense of safety, security, and newfound belonging, I realized my rehab journey hadn’t been for naught. In the new-old soil of home, the seeds of that intense journey could finally start to sprout.

After a few months, in which I learned to trust that this security was real, I felt ready for the next frontier. College. In Miami that Shabbos the rav had told me what I knew all along. That if I came from this town where mental health was so misunderstood, if I went through all this, I had a mission to help my own. If it wasn’t cardiology, it was a different sort of saving of the heart.

I knew I had it in me. I had the experience of working for my aunt’s clinic, connecting with children who needed help, and I’d also done so much of my own studying.

I decided to go to college for a bachelor’s in social work. With my parents’ support, I felt I could do it. I could find it in me to try something new, something big.

Only I couldn’t imagine how big. I’d been out there in the secular world. I thought I knew the culture, but college is its own beast. At the beginning, at LIU Post out in Long Island, I was ready to throw in the towel just about every day.

It wasn’t just the holes in my education, because, through learning Gemara, I’d learned how to learn anything. Maybe it was simply the immersion in regular life with all sorts of people who hadn’t been through intense journeys like mine. After all, I was still in a fragile place.

In yeshivah, you’re encouraged to ask questions, to discuss things together, but here professors were coming in with their slideshows, kings of the classroom.

I’d raise my hand and ask, “Can you please explain this?” or “What does that mean?”

They’d give me a quick response, while their look of horror showed what they really thought about the interruption.

In one of my very first classes, the sociology professor, wanting to show socioeconomic differences, brought in one of those ubiquitous New York Times articles about the chassidic school system and how chassidic kids aren’t able to go to college.

“Excuse me,” I said, raising my hand. “I went through the chassidic system and I’m sitting right here.”

Instead of being impressed, that got him angry. “Be quiet, that’s disrespectful.”

After that class some of the students went to the dean to complain about what had happened on my behalf. A few days later, that professor sent me an email. Would you like to meet me for coffee?

When we met, he wanted to hear my story, how I’d made it to college, and in our conversation, it emerged that he, too, was Jewish.

“You know what,” he said, as we left the café, “that was some story. You’re a brave guy, and I just want to let you know that I’m giving you a pass for sociology on the spot. You deserve it now already.”

On the family front, there was still a learning curve.

“Are you coming home for Rosh Hashanah?” my mother wanted to know.

I didn’t go. For now, I could only handle being around my family for chunks at a time — and Yom Tov felt too big. I joined Hillel on campus, gaining some sense of community. That first Rosh Hashanah, I enjoyed the familiarity of the meals and the davening. While I wasn’t fully observing the Yamim Tovim, I was participating, and that was a start and a comfort.

AT

LIU, weighing 280 pounds, with zero background in sports, I became an athlete, in a series of events that could only be Heavenly orchestrated. Growing up, I’d never spared a thought for sports. The unspoken rule was that once you were bar mitzvah, you shouldn’t play ball at all.

I was sitting in the cafeteria one day, when someone tapped me.

“Hey you, how would you like to be a D1 athlete?” he said, smiling broadly.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“Well, D1 is the best, the top tier of athletes. Usually, you’ve got to be on a certain level to even be recruited, but we’ve just opened a rowing team and we don’t have enough people. We’re looking for walk-ons. C’mon, it’s an opportunity.”

“Why me?”

“Because you’re here?”

Nothing about me said “athlete,” but somehow, he’d asked me and convinced me to show up to tryouts.

The coach had me sit on a rowing machine, called an ergometer, and pull as hard as I could. After just a few pulls, I was out of breath.

“If you’re willing to stick with it, we can work with you,” the coach said. “Show up for the next three days for training and we’ll see.”

I did, and huffed my way through.

Two weeks in, all of us on the team had to take the 2k erg test, a common fitness assessment for rowers, measuring endurance, power, and pacing.

I watched my teammates go. I went last, taking a full 12 minutes to complete the 2k (something that a nonathletic person could do in ten minutes, and a champion in six). I was red in the face, breathless, and I only got to the end since everyone was done and they were all watching me. They were rooting for me and I couldn’t let them down.

Someone had taken a clip and I watched it over and over, seeing my depleted self, their cheers of support, me making it to the end.

Something clicked for me. Teamwork, support, togetherness, that’s how we could make it. In rowing and in life. It’s not meant to be done alone. While my journey had been inward-focused, I now viscerally felt what the support of others could do.

I knew that from when my parents had come into my life again, how their support helped me pick up the pieces; and now, in the rowing gym, I’d experienced it again.

When we finally trained on the water, I was beset with nerves, terrified that I’d flip the boat, yelling at my teammates. I saw that if even one person in the boat is off, the boat veers and goes off course. I had to learn to trust my teammates, to hone in on our connection. Over time, I learned to work in sync with the others, and again, experientially, I knew that together we could do so much.

I started to become good at rowing. I learned endurance and discipline. I would lose 50 pounds and my lifestyle would become much healthier.

Varsity rowing gave me teamwork, health, camaraderie. I knew that when I picked up the oar, the others wanted me there. We needed one another. Together we could fly.

Rowing was my breakthrough and other things followed. While my mental health challenges might never be completely cured, I could be happy, healthy, fulfilled, successful. I found my recovery through teamwork and connection.

And not in the least through connection with my own family. My parents, too, were on my team. When we entered rowing competitions and races, my parents came to watch me. Their support meant everything. They were out of their comfort zone among the crowds watching the races, and yet they came to cheer me on, helping me to achieve what I couldn’t alone.

Alongside my studies, I undertook specific training to become a certified New York State Peer Specialist, as someone with lived experience who could provide peer support to people facing mental health or substance use challenges. A personal approach, to complement the traditional clinical approach, peer support is increasingly seen as a relatable and empowering means of guidance.

Three years ago, wanting to share my recovery with my own, I founded an organization called “Friends Like Family.” I help people from ultra-frum communities and other Jewish communities who, like I once was, are lost in mental health and addiction, trying to find their way.

We offer help at three levels: a peer-to-peer program for people who need friendship, “checking in,” and resource connections to help them find jobs. We have a recovery halfway house in Monroe, New York, similar to a sober living place, for both addiction and for anyone who needs a safe, productive, short-term environment after rehab, intense treatment, or a mental health episode. We also have a longer-term residential program for those struggling more intensely with comorbid conditions — more than one mental health disorder — where treatment is complicated.

I know that for frum people who need treatment, being removed from the world they know causes its own problems. I know how important it is that we offer high-level care within the community, and we work with rabbanim and dayanim who have a deep understanding of mental health.

How do I keep myself up when I’m in the trenches? It’s back to my own support system. My parents who are my anchors. My amazing siblings. They are what keeps me going. Together we are strong, we each have our own strengths, and we support one another in turning that outward towards the klal. My mom runs her group and coaches others, one of my brothers is an EMT and another has a big role in a community organization. I work with unbelievably dedicated colleagues, and have a wonderful circle of friends and people in the recovery community.

This is the story of Yehuda. At college they called me Leo, Latin for lion, and I like to think I have a little of those qualities — boldness, courage, maybe even leadership. But it’s also my parents’ story. How when the lion was slumped and limp, all but defeated, they helped me find my feet and get up again.

They’re a huge part of why I can do what I do today, and for me, recovery will always mean connection. It’s the theme of my work and my life. Because life is bigger than you or me, but together we can row a river; together we can heal.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1064)

Oops! We could not locate your form.