Seeker’s Choice

When I was a Muslim, I laughed at those shtreimels. Now I'm wearing one

As told to Rivka Streicher by Ephraim Nachman

W

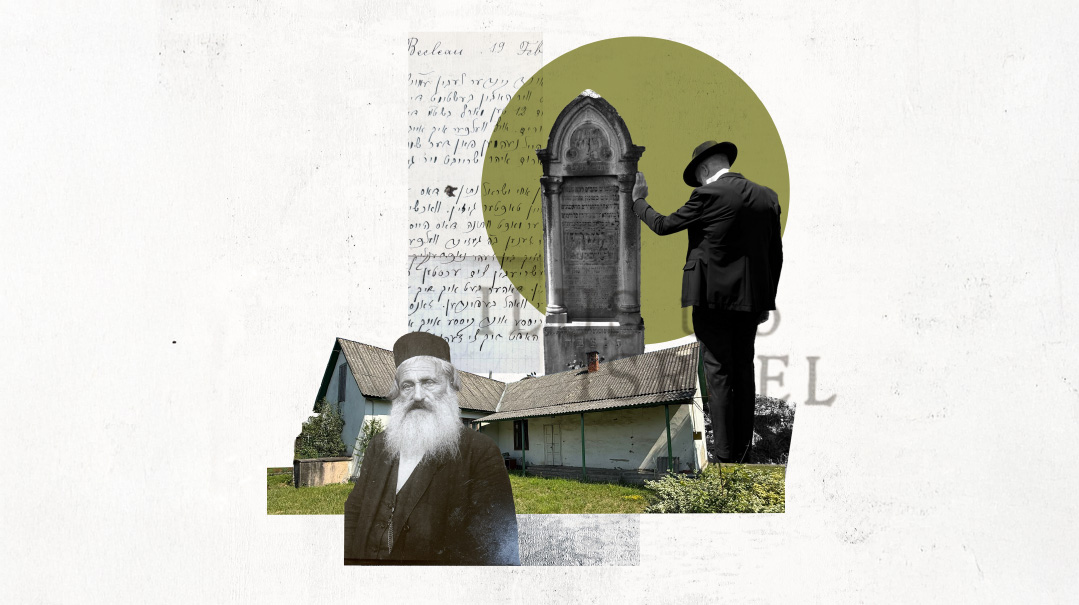

hen I was a young kid growing up in Williamsburg in Brooklyn, nothing looked weirder to me than the chassidic guys who lived on the other side of the Marcy Avenue train station. We’d see them walking by with their long side curls, big beards, black coats — and sometimes with striped blankets and fur hats.

What on earth?! I thought.

I was a Puerto Rican kid growing up in a melting pot of minorities, most notably Hispanics and Blacks, and venturing into the chassidic community of Williamsburg was like stepping into Eastern Europe. They seemed intent on staying apart, with their archaic garb and a language of their own to boot.

Later in my life, I’d hear others denigrate them and point to them as the source of our problems. Even later than that, while it would’ve been the most ludicrous thing you could’ve told me, I’d end up looking like them.

MYparents divorced when I was very young, and I grew up with my mom and her parents. Our home wasn’t in the best part of town, and my mom sent me to live with my grandparents, where I’d be in a better school district.

Mom worked hard, holding down two jobs while going to school, trying to make a good life for us. My grandfather, Grandpa Francisco, was my man. While my dad was also involved in my life, Grandpa was the guy I’d see every day, the man I wanted to be.

He was inventive and creative and could do just about anything with his hands; he could build a house from scratch. He understood how things worked, not just engineering and electronics — though he knew those well — but everything. His mind was open, big; he was always thinking. I loved Grandpa, and I wanted to one day be a husband like him, a father like him, a man like him.

He had dreamed of serving his country at sea. He’d signed up back in the day, but had been turned down because of his chronic asthma.

“Papito,” Grandpa would say to me, using a Puerto Rican endearment, “if only I could’ve gone to the Navy.”

My family was religious, church-going folks who went to prayers every Sunday. G-d was often invoked in our home; I believed in Him from early on, and we knew that nothing happens unless G-d wills it.

As a kid, I’d go to church meetings and on church outings. I knew a lot of the Bible, the stories, and the morals, and how to be a good person. Religion was important to me, as it was to my family. In good Christian tradition, I wanted to save others’ souls as well. I thought that if I familiarize myself with other religions, I’d be better equipped to find the mistakes and convince others of the truth.

I started with Islam. Reading the Koran, I recognized its similarity to the Bible. I recognized my prophets, my kings, my messiah — whom the Muslims acknowledge as a prophet of G-d, albeit not the son of G-d. The only new name was Muhammad.

My goal was to learn about Islam to refute it. But as I learned, I realized that the Muslims worship G-d, not the messenger. This felt like truer monotheism than Christianity, and unwittingly, the seeds of doubt were sown.

I was a truth-seeker, and now that I had serious doubts about Christianity, I might have considered learning more about Judaism, too. But I couldn’t. I knew there’s no mention of Yoshke in the Torah, and I couldn’t let go of him. For years, I’d known him as someone who had sacrificed himself for us, bearing our suffering so that we could live good lives. In our home he was loved almost like a parent. I couldn’t let go. Islam, which acknowledged him as a prophet of G-d, but where I would serve G-d alone, seemed like the answer.

Oops! We could not locate your form.