Scroll Up

The recovery of forgotten mesorah and lost minhagim that once flourished in the pre-modern world of safrus

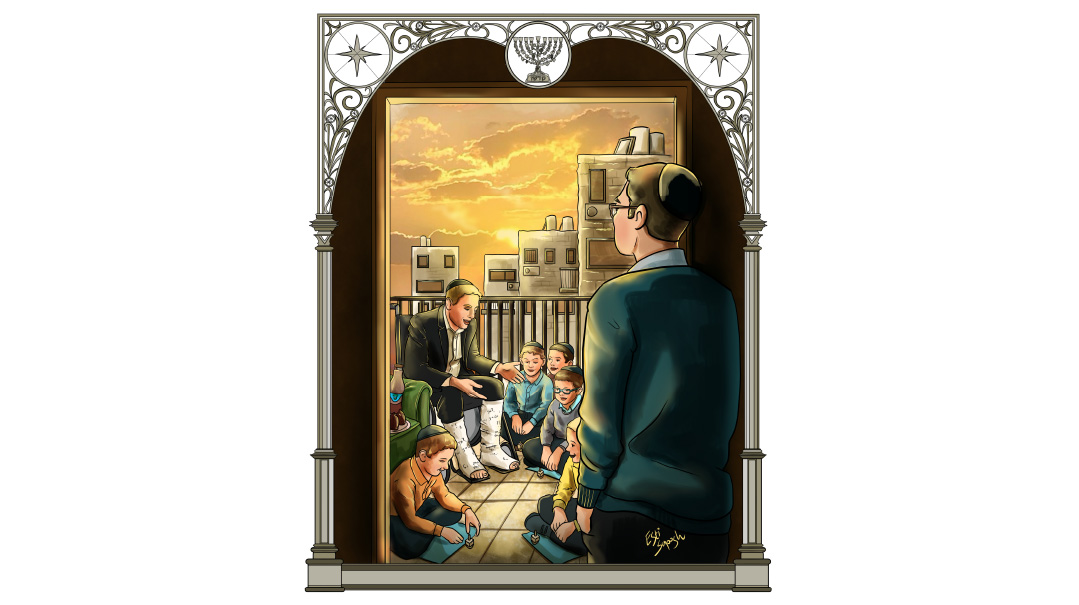

Photos: Elchonon Kotler

When Avraham Strauss received his first calligraphy set as a young boy, he had no idea that his new hobby would one day develop into restoring the ancient scripts from as far back as the Rishonim, a mission that could have a ripple effect on the entire STaM industry. His is a quiet revolution: the recovery of forgotten mesorah and lost minhagim that once flourished in the pre-modern world of safrus

IN a small room adjoining his home in Ramat Beit Shemesh, ink pools in a tiny dish and the sound of a feather quill scratching parchment faintly echoes, as Rabbi Avraham Strauss puts the final letters on the last folio of a nearly complete sefer Torah. But this is no ordinary Torah scroll — it’s a hands-on, living mesorah of how sacred texts were once written.

Rabbi Strauss is at the forefront of a small cadre of sofrim whose mission is to bring back ancient writing traditions that might have otherwise been relegated to the dustbin of history. His is a quiet revolution: the recovery of forgotten mesorah and lost scripts that once flourished in the premodern Jewish world. It’s a complex tapestry of mesorah, halachic debate, historical shifts, and practical questions surrounding ksav, sofrim, and our relationship with earlier generations.

The sefer Torah — the 12th one he’s written, this one a self-commission in fulfillment of the mitzvah of writing a personal Torah scroll — is a testimony to his research. It’s written primarily according to the custom of the Rema, the great 16th-century Ashkenazi posek, with certain stylistic nuances that today have virtually disappeared.

Still, there is no copy of the Rema’s sefer Torah in existence today, so how does he know what was different than the modern standard?

“It’s true that no one has a copy of the Rema’s sefer Torah,” Rabbi Strauss explains, “but what we do have are some very old scrolls that we know are pretty much identical, that followed the Rema’s traditions. In the manuscripts department at Hebrew University, you can find entire sifrei Torah from up to 700 years ago, so we see the differences between then and now.”

Rabbi Strauss says that World War II was an inevitable cause of a rupture in European scribal tradition because so much was lost, both in terms of documentation and in sofrim themselves, who passed on certain traditions that vanished after the war. That’s also when the Rema’s Torah scroll — which endured for close to 400 years — disappeared.

“We have accurate documentation that at the beginning of the war, the Rema’s sefer Torah was hidden with a Christian family,” Rabbi Strauss relates. “But they were too frightened to keep it, so they sent it back to the Jews, who hid it along with other scrolls at the gate to the entrance to the old Krakow cemetery, which the Germans later destroyed.”

After the war, three different sifrei Torah turned up by dealers, each one claiming to be the Rema’s scroll. But it turns out they had been “corrected” to make them correspond with the opinions of the Rema, and they were fakes.

“You didn’t need to be a big expert to see that those scrolls were tampered with,” Rabbi Strauss says.

In the ensuing years, there became a dire need for standardization in the STaM [an acronym for sifrei Torah, tefillin, and mezuzos] industry, which had become a free-for-all market; in 1976, Vaad Mishmeres Stam was established by Rabbi Dovid Leib Greenfield with the backing of Rav Shmuel HaLevi Wosner, in order to get rid of the charlatans, create an umbrella of supervision across the industry, and make sure every sofer complies with all halachic requirements.

But with the blessing of quality control came some collateral damage as well, according to Rabbi Strauss. Accreditation and accountability meant a huge and long-awaited clean-up and elevation of industry standards, but at the same time, the modern halachic rulings and highly regulated supervision meant that a lot of the old traditions were either lost, ignored, or considered bedi’eved. Some kosher, even mehudar prewar STaM items might even be considered passul today.

W

hen Avraham Strauss received his first calligraphy set as a young boy in Kew Gardens Hills, he had no idea that his hobby would one day develop into restoring the ancient scripts from as far back as the Rishonim, a mission that could have a ripple effect on the entire safrus industry. When he was growing up, his family davened in Young Israel of Queens Valley, and later in Rav Elchanan Teitz’s shul; he attended yeshivah day school at Yeshiva of Central Queens (YCQ) and then for high school moved on to Ramaz on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

Ramaz wasn’t exactly a standard springboard for a high-level yeshivah education, but when Avraham was 16, he was already dabbling in safrus. That’s when he began learning with Rabbi Shmuel Schneid, an expert in Jewish scribal arts.

“My grandparents lived in Washington Heights,” he says, “so once a week, instead of going back to Queens, I’d go to Washington Heights and learn for two hours with Rabbi Schneid.”

Rabbi Schneid, who lives in Monsey today, is no ordinary sofer. He has devoted decades to reclaiming age-old traditions from historical obscurity, and has taught his students not only the art of safrus, but how to access traditions on the brink of being lost.

Rabbi Schneid began comparing and contrasting sifrei Torah from different times and places, and realized that there were entire styles of sacred writing that had all but disappeared. Through his research, Rabbi Schneid began to see that certain things appearing in the poskim regarding how to write holy letters were difficult to understand based on our modern STaM because some changes evolved over the centuries; and in seeking out elder European sofrim and seeing old collections of STaM from diverse communities around the world, he realized that there were traditions we no longer have. He was distressed by modern sofrim redoing old pairs of European tefillin as if the sofrim of the last centuries didn’t know what they were doing; disheartened that although various chumros that were introduced for quality control purposes helped to standardize the industry, they also wound up replacing some of the mesorah of prewar safrus.

Avraham Strauss was fascinated by the research, but put his own safrus on hold when he went to Eretz Yisrael after high school for a year at Yeshivat Shaalvim. Upon his return to the US, he went on to learn in Or Hachaim in Kew Gardens Hills, attended Queens College at night, married Elisheva Zabrowsky of Far Rockaway, and spent shanah rishonah in the Or Hachaim kollel. He tried his hand at teaching, spending a year as a sixth-grade rebbi at HANC in West Hempstead, and had also gone back to safrus, writing and checking STaM to supplement his income.

In 1994, the young Strauss family returned to Eretz Yisrael, where Reb Avraham spent the next nine years in Shaalvim’s kollel — five years on campus and the next four after moving to Ramat Beit Shemesh. He also continued to write and check STaM, working with a distributor who he’d connected to in the US.

In Eretz Yisrael, he made sure to take advantage of studying with the person considered Klal Yisrael’s greatest sofer, Rav Menachem Davidovitch, a Toldos Avraham Yitzchak chassid from Meah Shearim and known as “avi avos hasofrim,” whose shiur Reb Avraham attended for about ten years, until Reb Menachem’s passing in 2017.

“Almost every Ashkenazi sofer today is probably a second-generation talmid of his, through him or one of his students,” Reb Avraham says. “Everyone in the safrus industry had a connection to him.”

A

lthough Avraham Strauss had studied with Rabbi Schneid as a bochur and was exposed to his research, he himself kept to pretty standard safrus, until he decided to research how to write a sefer Torah as per the minhag of his ancestors.

“We’re from an Ashkenazi family from Frankfurt am Main, my father grew up in Rav Breuer’s kehillah in Washington Heights, and I became curious about the various yekkishe minhagim,” Reb Avraham relates. “There’s a talmid chacham in Eretz Yisrael named Rav Binyamin Hamburger who runs a chain of these old-style Ashkenazi shuls in different communities around the country, and I contacted him for help in clarifying the Ashkenazi minhagim in writing sifrei Torah. Well, he didn’t really know too much about this particular area, and as I was a sofer, he basically appointed me to find out. He told me to contact a young man named Yehoshua Yankelevitch, who at the time was a bochur learning in Lakewood.”

Today Rabbi Yankelevitch is a well-known avreich in Jerusalem, one of the leading experts in ancient Torah scrolls. He has a massive collection of Torah parchments, whole scrolls and parts, ancient megillahs and Navi klafim, all of which he’s collected from around the world and keeps in a gallery as a service for scholars to peruse.

At the time, though, Yankelevitch was just getting started — and he, too, happened to be a talmid of Rabbi Schneid.

With the tools Rabbi Schneid had given him, Yankelevitch learned that while today there are two major ksav styles, Ashkenazi and Sephardi, and within the Ashkenazi style, there is the ksav Beis Yosef and the ksav Arizal, there used to be an older Ashkenazi ksav that predated the current one that’s used, and that’s the one the Ashkenazi Rishonim were referring to. He began to research how the ksav gradually shifted from this old Ashkenazi ksav to the contemporary style — for example, how one part of a letter gradually got longer while another part got shorter — and eventually, using those and other indicators, was able to develop a system to determine when a particular ksav was written.

Once the two of them connected, the discovery of old styles became Rabbi Strauss’s passion as well.

“If we say we follow the Ashkenazi tradition,” he explains, “then let’s clarify what that tradition really was, from the time of the Rishonim.”

Why don’t we have scrolls written the way our ancestors had them? How did the style disappear?

“It’s more like the style subtly changed,” Rabbi Strauss relates. “What happens is that in every generation, you have sofrim who think, this letter should probably be readjusted, I think it’s a better fit for the halachic description…. Now imagine that this has been going on for 700 years. Even in this generation, just within the last 30 years there’s been a huge discussion about the width of the bottom of the letter lamed. Rav Elyashiv said one thing, certain sofrim say another, and everyone is trying to reconstruct what they think is most accurate. So what happens is that over time, every couple of decades there’s a tiny shift.

“But what that means is that if someone goes back to write in the ksav of the 13th-century Maharam of Rottenberg, for example, most sofrim will look at it and say, ‘What is this? Whoever wrote this definitely doesn’t know what he’s doing.’”

The good news is that according to the Shulchan Aruch, there are not many things actually make a letter passul: In broad terms, it is passul only if it looks like a different letter, or if it’s simply unrecognizable.

Rabbi Strauss doesn’t want to shock anyone, but he says one of the major problems with today’s safrus in the historical context is that modern letters are based on a questionable sefer.

“The old Ashkenazi ksav is really closer to what we call Ksav Ari, as opposed to the more modern Lithuanian style,” he explains. “What we consider today’s standard ksav is based on a sefer called Kesivah Tama, written by a sofer in Minsk in 1858, who claimed to be the one to be holding onto the mesorah of the Gra.

“Now, what I, and several others over the years have discovered, is that this sefer, considered the definitive arbiter of halachic ksav, is problematic for several reasons. I have a copy of the original manuscript, which includes parts that weren’t printed for the public, including an introduction in which the author — a self-admitted ‘heavy Litvak’ — openly states that the purpose of the sefer is to prove that the Sephardim and the chassidim have a mistaken mesorah.

“He had an agenda, and used questionable sources as his proofs. I systematically reviewed the sefer, going through every source line by line, for every single letter, and I exposed every place where there was an inaccuracy or a misconstrued or doctored-up source of the Rishonim. The main reason Kesivah Tama got away with all these ‘readjustments’ on the wording of the Rishonim was because almost no one had a copy of the seforim he was quoting from. But today, we do have access, and we can see that the quoted sources are often manipulated and inaccurate.”

Rabbi Strauss’s review was printed in a widely circulated kuntres, that he published for his recent personal hachnassas sefer Torah, and will appear this summer in Yeshurun Torah journal.

There have, in fact, been several attempts to clarify this over the years, including a sefer printed in 1970 that has a few lines making reference to the inaccuracy of “the sefer that we follow.” There are also articles by Rav Greenfield of the Vaad Mishmeres Stam, addressing what he felt were mistakes in certain letters. But it’s a complex parshah, especially as the Mishnah Berurah and the Chazon Ish seemed to have followed the Kesivah Tama, which further cemented it as the modern standard, despite some significant divergences from older ksav styles.

AS

we have access to more and more old manuscripts and have the ability to find more and more discrepancies, where does that leave us regarding our sifrei Torah, mezuzos, and tefillin?

“Rav Elyashiv was of the opinion that despite new discoveries, we should leave things the way they are, maintain current standards, and that we should follow whatever the previous generation did,” Rabbi Strauss says. “When I discussed my findings with Rav Shmuel HaLevi Wosner, however, he encouraged me to go back to the old style if I found something that was clearly misrepresented by what people are doing today — although a lot of my discoveries happened after he passed away.”

Rabbi Strauss mentions the extra space between pesukim, what we call double-space. As we know, if you look at any sefer Torah today, you’ll see that there is no double-space break between sentences, but that wasn’t always the case.

“All the Ashkenazi sofrim used to do a double-space between pesukim,” Rabbi Strauss relates, “and although the Vilna Gaon held not to double-space, that was the standard practice for at least 900 years until the early 1900s, especially in the Jewish communities of Germany, Austria, and Hungary.

“When I discussed this with Rav Elyashiv, he said to leave it be, to keep to the Gra and how we’ve been doing it, and not make any changes. But when I mentioned it to Rav Wosner, who came from Austria, he shrugged his shoulders and said, ‘I don’t know, when I grew up, we double-spaced.’”

Rabbi Strauss mentions a rav from Monsey who had a collection of old Russian tefillin that he gave to a sofer to check. The letter pei was written as a “double pei,” one pei within another, and the ches had a little foot-like extension on the bottom of the letter. When the sofer returned the tefillin, he said he’d fixed the parshiyos — he removed the inner pei and cut off the foot of the ches.

“But what this sofer didn’t know,” Rabbi Strauss explains, “is that the pei kefulah and the little foot on the bottom of the ches is a minhag that goes back at least 1,000 to 1,500 years. It’s extremely likely that the sofer who fixed it didn’t know that.”

The big question, says Rabbi Strauss, is what to do with all this information.

“The bottom line is that in order to get accredited as a sofer, you need to know the Mishnah Berurah very well, and also the halachah sefer from the author of the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch. The vast majority of sofrim learn material they need for the test and to produce what will sell in the market of STaM, but most don’t really know much beyond that. It’s not demanded of them, and you really can’t expect everyone to know every piece of information that’s been floating around for the last 1,500 years.”

He explains what some of those differences are, how some letters have developed and changed.

“For example,” he says, “the bottom of the shin in the time of the Maharam and his talmidim, and we’re talking 800 years ago, is completely round. Also, the “yud” of the letter alef looks like it’s written backward in relation to the alef we’re used to.

“I think the major issue here is awareness, awareness that we might not be totally accurate, even though we’re confident that we know best because we live in the so-called information generation. Yet it’s exactly that fact — that we now have information we never had before — that should make us more humble. No one a hundred years ago ever saw a sefer Torah from 800 years ago, but today, libraries across the world have digitalized photographs of ancient scrolls from towns all over Europe, so that we can also examine the evolution and the changes.”

There is humilty in realizing that what we think we know hasn’t always been the case. And there is humility in accepting the psakim of our gedolim today, as that is the current mesorah.

Either way, says Rabbi Strauss, “we bow our heads.”

IN

several chassidic courts, including Belz, Satmar, and Bobov, where there is a shift to go back to the mesorah of the old rebbes, they’ve actually adjusted some of the letters. In Chabad, the Kesivah Tama was never accepted, and they still use the style of the Baal HaTanya.

“In the chassidic courts,” Reb Avraham says, “there is a movement to go back to the old style, and they’ve been in contact with me to help them find out what their original mesorah was. But I get requests from all over. Just this week I got a call from a yeshivish guy in Lakewood who realized that what is today’s standard doesn’t match what the Rishonim say, and he wants an adjusted pair of tefillin for his son.”

Still, most of Rabbi Strauss’s clients are ordering items with the standard ksav.

“When someone orders tefillin or any other item, and they don’t know about all this background, I just write like every other sofer,” he says. “But I do get requests from people who’ve found out about me and will tell me, ‘I want to order a sefer Torah like the real authentic style of the 1400s,’ or ‘I want tefillin like the Maharam and his talmidim.’ And I’m happy to do it for them.”

Yisrael Feller contributed to this report.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1063)

Oops! We could not locate your form.