Driven Off Course

| April 8, 2025Sometimes I feel like I’m ten again, a child they expect to behave in predictable ways

I haven’t seen Rus since she robbed me of twenty thousand dollars.

Twenty thousand, if you add all the costs. Three thousand for repairs because I didn’t have collision insurance, weeks of an unreliable car that just wasn’t going to be revived from the dead. Another five hundred for Ubers during that miserable month when I hadn’t come to terms with the fact that my van was a lost cause. Twenty-five hundred for the temporary rental. Fifteen thousand for the used minivan we’d finally gotten to replace it, thanks to predatory interest rates and No. Choice. At all.

And that wasn’t even the full cost. Ma and Ta had chipped in, for my silence. It hadn’t been phrased like that, but it had been implied. Rus has so much going on, Malky. She doesn’t need this on her plate, too.

Right. I’ve been protecting Rus since I turned two. I know the drill.

It’s easier when she’s across the country, when we don’t talk at all except through snatches of interactions by text, but Pesach is for family, the six of us and our kids and Ma and Ta all spread out across a luxurious house in the Catskills. Ma and Ta save up each year for the splurge.

This year, it’s all fixed smiles after the kashering crew is done and everyone slowly begins to fill up the house. We brought most of the food up with us, but Tali and I cook a little extra for the Seder today, taking turns at the stove to mix our semi-decent sauce concoctions. “Ma should be back from the airport soon,” Tali comments, stirring a cranberry mixture that smells almost like chometz. “Rus’s flight was delayed. She said she was sitting in the airport for an extra hour with the kids going out of their minds.”

“Mmm.” It’s all I can think of to say. When I dwell on Rus too much, the unfairness of it all seems to burst from me, and I’m trying to behave.

Tali gives me a hard look. “You’re not going to talk about the car with her, are you?”

“Talk about the car? Me?” I focus on the recipe in front of me, counting out half-cups of almond flour. “Why would I ever mention that to Rus? What does Rus have to do with my car? Except the part where she borrowed it last Pesach, punctured the oil pan, and destroyed the engine beyond repair, I mean.”

“She didn’t know.” Tali elbows me, and extra almond flour sprays from the bag into the bowl. “And she has enough stress. Between her medical stuff and custody arrangements, she’s having a rough time of it. Sometimes, you just have to let it go.”

“I didn’t say I wasn’t going to let it go.” I try not to sound defensive. I always sound a little defensive when it comes to Rus.

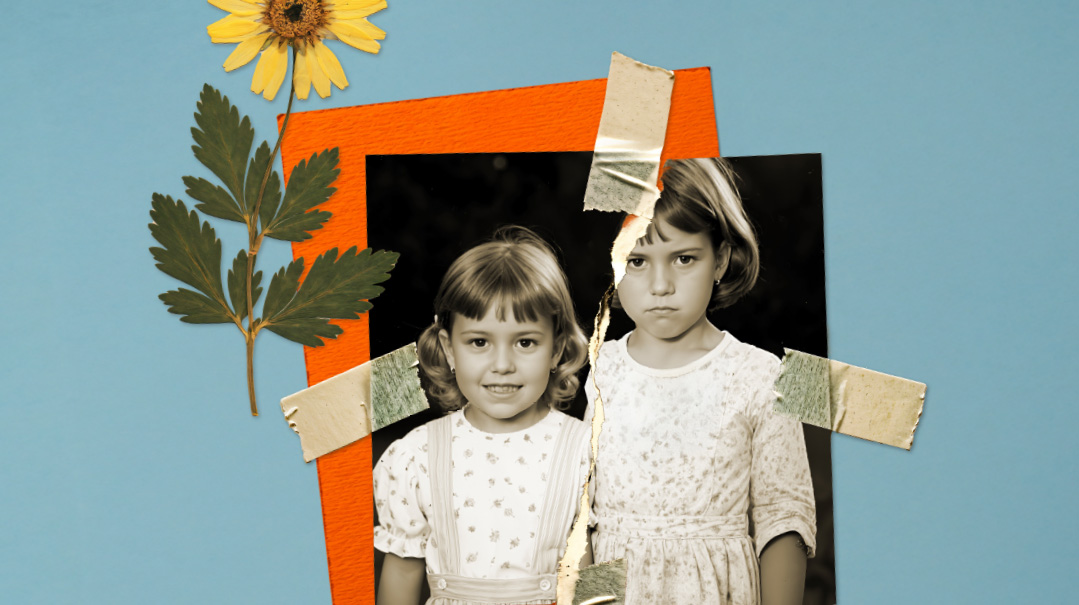

Maybe it’s because there’s an age gap between us and my other siblings. Tali is five years older than me, already seven when Rus was born. Moshe and Ari, older than her, were never all that involved in taking care of Rus. And Shaina is a full 12 years older than Rus, nearly parental.

Rus is everyone else’s baby. But she’s my sister, clingy and annoying in childhood, prone to bursting into tears whenever we’d have an argument. Can’t you try to be a little more sensitive? Ma would sigh to me. Rus was always sickly, had celiac and asthma and acute allergies, and I was perpetually the villain.

It didn’t matter that she’d pick fights with me, that she’d take my things and then sob when I took them back. Share, Malky. That she’d ruin my homework. It’s not a big deal, Malky. That she’d whine until I gave up the phone, bother my friends when they were over, argue with me and then run for an arbiter, a parent or older sibling who would inevitably take her side. Stop picking on Rus, Malky.

Anyway. That was childhood. We’re adults now.

So I plaster a smile on my face when the door opens and Rus’s three boys tear into the house in a whirl of uncontrolled energy.

“I call the banister first!”

“Hey, give me that!” I hear the wail of protest from my five-year-old, the stirrings of a fight in the playroom.

Tali raises her voice. “No sliding down the banister!” she orders. If no one stops Rus’s kids, they’ll tear apart the house and cost a fortune in surcharges. Rus certainly isn’t stopping them.

Rus, who greets us with a light, “Hey, Tali. Hey, Malky.” She looks paler this year, a little more frail than usual. Beside her, Ma is giving me a death stare. I can almost feel the don’t talk about the car hovering thick between us. “How’s it going?”

I don’t talk about the car. My words are abrupt, uncomfortable. “It’s fine. You know. These cookies aren’t bad.”

Rus swipes at the batter without washing her hands, takes a lick. “Eh.” She makes a face. “I have much better gluten-free stuff at home. Somehow, making it Pesachdig makes it worse.”

“Really polite, Rus,” I drawl. Adulthood is learning how to smooth my irritated comments, make them sound amused instead of annoyed.

Ma senses it anyway and shoots me a look. “Oh, Rus is just used to these things because of her celiac. She has a more refined palate,” she says before Rus can respond.

Rus doesn’t offer to help with the last few items, of course, even though she’s more of a pro at Pesach cooking than anyone else. She has to catch up, and she wanders out to the patio to find Shaina and our sisters-in-law while Ma returns to cook with us.

“Malky, you’re not going to mention—” Her voice is tense.

“I didn’t say anything about it, did I?” I shoot back.

It’s going to be a long Pesach.

MY

kids are in hand-me-downs for the Seder, mismatched from each other and slightly less trendy than their cousins. We’re still feeling the strain from the car, a monthly expense that means we have to be more careful this year. It’s not a big deal. Little Faigy is still glowing with pride at her flowy Shabbos robe, twirling in circles near the table and curtsying after she does the Mah Nishtanah. She doesn’t notice her cousins in their perfectly matching pajamas and robes, but it makes me flush when Tali makes a light comment about how pretty Aliza’s daughters look, about how I can’t do the same for my kids.

The children drift off to the playroom as the Seder continues, and I do my best to focus. Rus’s oldest, Nachi, has the seat of honor on Ta’s lap, and he chatters over everything Ta says, reaching into the Seder plate to grab at the matzos whenever Ta is distracted.

Ta bats his hand away, unbothered. “Let’s run through the pesukim. We’ll go around.”

“I wanna read one! I can read!” insists Nachi.

Ta smiles indulgently. “How about you do the first line?”

Nachi, we discover quickly, is very, very slow. Ta coaxes the words out of him while Rus, right beside Ma, leans forward to watch, her face shining with pride.

“He’s been working hard,” she says when he’s done. “They use a different kriah system in his yeshivah.”

“Really?” Moshe’s wife is a kriah teacher, and she leans forward, interested. The Seder is officially derailed, and I feel my eyes glaze over, the exhaustion of all the cooking and managing the kids beginning to set in. Nachi escapes to the playroom. I allow myself an instant of envy.

And then, predictably, a cry from the playroom, followed by a shout from Shaina’s oldest, who’d been supervising. “Tante Malky!”

I hurry away from the table to break up a fight and discover something much worse.

Faigy’s new-used robe is torn at the seam, the bottom half of the skirt totally detached. Nachi is standing next to her, looking caught.

“He grabbed it when we were playing tag!” Faigy wails. “It’s broken!”

“Oh, no, sweetie.” I hold my arms out to her, let her burrow into me as she sobs. “I’m so, so sorry.”

Nachi returns to the toys, satisfied he isn’t getting in trouble. I don’t know how I could, not without aggravating the Rus Defense Squad. I just hold Faigy tightly, whispering apologies in her ear, and do a mental calculation of how much clothing we’ve brought. She has last year’s robe in her suitcase, though if she wears it tonight and tomorrow night, it’ll be yet another thing to add to the inevitable Chol Hamoed load—

“Oh, poor Faigy!” Rus says from the doorway, jerking me from my thoughts. Her eyes are wide and sympathetic, though there is no guilt in them. “What happened to your dress?”

Faigy has no compunctions about sharing the truth. “Nachi ripped it!”

“Oh.” Rus’s face tightens. I stare at her, daring her to do something. To acknowledge that, yet again, something of mine has been destroyed by her.

Then she smiles. “Ma still has her sewing machine, right? It’s just on the seam, should be easy to repair. I can sew.” She’s also leaving Isru Chag and won’t remember that she’d promised to fix the dress, but I don’t say that.

Instead, we linger in awkward silence in the playroom. During the year, Rus spends hours on the phone with Ma, with Tali, with Ari’s wife, Aliza. We don’t really talk, and no one expects us to. All I know about her life I’ve heard from Ma or through photos.

I’m not making small talk with her now, no way. I’m on edge already, keeling over under the weight of everyone else’s glares, the constant unspoken warning of move on already. I just hug Faigy and watch my little ones play.

“How’ve you been, Malky?” Rus says finally. “Ma says your upsheren was nice.”

“It was just cake and friends.” I’d wanted to rent a bouncy house, something a little more exciting than the swing set, but it had been just after we’d bought the new car. “Nothing special.”

“Those are the only things the kids really care about,” Rus offers. “One of our neighbors brought in a petting zoo for the kids. But realistically, these are three-year-olds. They’re going to have a good time as long as there’s cake.”

“One of the kids at Shua’s nursery brought in a magician. For toddlers.” I shake my head. It’s a special kind of torment, watching the other women compete to outdo each other, and it’s easier to roll my eyes than to think about why I can’t join the crew. “None of the adults cared, and none of the kids followed. It was ridiculous.”

“Uri’s is next.” Rus waves in the direction of her youngest, fast asleep on the couch beside my Shua. “I’m going to follow your lead and stick with cake.”

“You allow cake in your house?” I ask curiously. We exclusively had gluten-free desserts throughout my childhood, because Ma wanted Rus to feel included at birthday parties.

Rus gives me a look. “I have children. I’m not a monster,” she says, and I laugh. It’s scratchy in my throat, unfamiliar.

Rus clears her throat. “I wanted to ask you—” she begins, but she’s cut off by footsteps racing toward us and Shaina appearing in the doorway, breathing hard.

“Malky! Ma needs your help in the kitchen,” she says, shooting me a significant look. Don’t mention the car. Her voice turns more solicitous. “Rus, do you need to rest? No one will hold it against you if you want to leave the Seder early.”

Rus chews on her lip. “I’m really hungry,” she admits. “I’d rather stay up for Shulchan Oreich.”

“You can eat now. We’ll set up some food for you.”

When we return to the table, the Seder is at a standstill, the men arguing about one of the pesukim while our stomachs growl. Rus murmurs the rest of Maggid to herself and runs through the meal, then disappears to bed, leaving Nachi to knock over wine cups and wreak havoc through the rest of the Seder.

“He’s adorable,” Ma sighs after the meal. “So much energy! Malky, do you mind putting him to bed?”

I do mind. I’m exhausted and wrestling a five-year-old into a bed is the last thing I want to do. But Shmuli takes care of our kids, and I’m left negotiating Nachi into a top bunk and carrying Uri into Rus’s room to lay him down on the second bed.

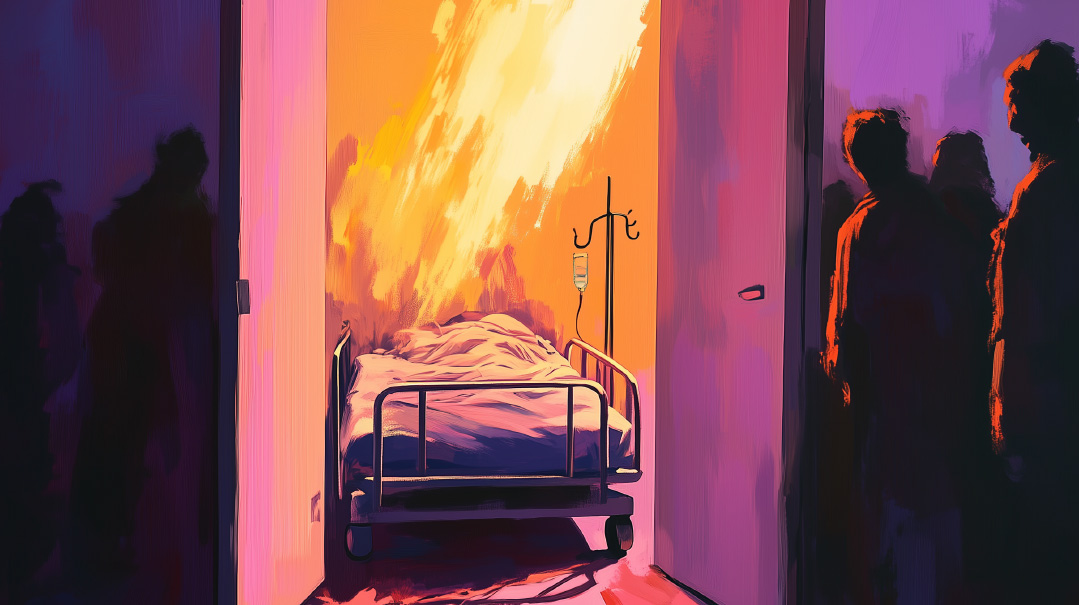

I pause outside her door, and Tali gives me a sharp look as she passes by. “Let her sleep,” she says reprovingly. “You know she’s not doing great.”

Rus needs to be cared for, needs a dozen advocates wherever she goes. Twenty-eight years old, and she’s still everyone’s baby.

I don’t have to grin. I just have to bear it.

“T

here’s a frightening aura around you,” Shmuli says the next afternoon. We’re out on the patio supervising the kids. Shmuli has a sefer in front of him, I have a magazine, but we’re not getting much done. There are 26 kids in total, and all other adults have disappeared.

“A frightening aura,” I repeat. “You sound like your sister.”

Shmuli laughs. “I think I finally get my sister. It’s like there’s a thundercloud around you, and it’s about to drench anyone who gets too close.” He grows serious, his eyes on the spot where Nachi is terrorizing Tali’s twins. “Rus?”

“Pesach is hard,” is all I say, diplomatic. Sometimes I feel like I’m ten again around all this family, a child they expect to behave in predictable ways. Like I’m still the kid who doesn’t measure up, the one who doesn’t do anything right. I’m on edge, waiting for the explosions, for the tears and the shouting and the moment I have to run up to my room and slam the door and hide for the rest of the day. And Ma watches me like she half expects it.

She never does that when Rus isn’t around. Without Rus, I can be trusted to be an adult, to be good and reliable and kind. The insecurities are still there — that knowledge that the others are giving their kids more exciting lives — but even their pity would be better than their wariness. When Rus enters the house, everyone is suddenly on alert, warning bells blaring. Emergency. Malky is about to attack Rus. Emergency.

“It’s just… we’ve been paying off this new car all year,” I say at last. “It’s hurt us. We don’t have the money for it. And I get that Rus can’t afford to— I’m not asking her for the money. But I would like her to know what she did.”

Shmuli glances at me. “So she doesn’t do it again?”

“Exactly!” Shmuli, at least, understands me. I’ve told him what it was like, growing up with Rus. He’s seen the way that even now, sometimes, our arguments end in tears, the way the rest of the family scrambles after her and shake their heads at me.

“Do you plan to lend our new minivan to her?” Shmuli’s voice is gentle, the way it gets when he’s guiding the kids toward a realization.

I cast him a wary look. “Definitely not. It’s for… it’s so she’ll recognize the signs and not ignore warning lights if she borrows someone else’s car. She needs to be more considerate. She needs to think of others for once in her life.”

I watch Nachi, kicking wildly from the monkey bars and whacking an older cousin in the face. “I know she has a hard life. I get that. I try to be… it’s not that I don’t feel bad for her. It’s just that none of it really excuses the way she treats me.” How she ruins, she breaks, she takes and takes and takes until there’s nothing left but a shattered husk.

Someone’s crying. Nachi has jumped onto another cousin. I head down to the yard to supervise, to order them apart and bribe Nachi into playing somewhere else. I think for a moment of the Shabbos afternoon that Shua had bitten a cousin and Tali had banged on my door until I’d awakened, demanding I take care of my son.

Rus doesn’t get banged doors. She emerges an hour later, fresh-faced and smiling, and says, “Oh, kids are kids,” when I tell her about Nachi. “Look, they’re all friends again.” She waves at the kids outside, playing some elaborate game of capture the flag, the high drama of earlier forgotten.

“Because I stopped them from killing each other,” I say pointedly.

Rus laughs, a little condescending and defensive at once. “Your big ones are girls. You’ll get it eventually.”

I could point out that I have four and she has three, my oldest is seven and hers is five, and there isn’t really much of a difference between how much supervision five-year-old boys and three-year-old boys need. But I see Ma across the room, her lips pressed together disapprovingly as she anticipates my response, and I say, “How would you know?” and escape to my room like I’m ten again.

I

can’t go back out there, so I leave Shmuli schmoozing with the men and watching the kids while I read in my room, squinting in the dim light of the Shabbos lamp to catch the tiny words on the page.

At the second Seder, my little kids are already in bed and Faigy only makes it to Arba’ah Banim before she’s out. It’s an excuse for me to withdraw, to sit at the table and tune out any conversation. I’m far from Rus, and I stare out the window, catch sight of my new-used clunker parked in front of the house, paint already rubbed thin in obvious places.

When I turn back, I see Rus watching me, her brow creased. I open my mouth — the truth is on the tip of my tongue, threatening to escape — and then I snap it shut again.

There’s no point. It would only ruin the Seder. I can only be the villain, or I can be invisible.

Rus isn’t feeling well again, leaves the table early, and I breathe once she’s finally gone. Things become less tense, more natural, and even Nachi hiding under the table and trying to tickle everyone’s feet can’t ruin the fact that I’m beginning to relax, finally having a good time. Ari and Shmuli steal the afikomen from Ta. Shaina’s preteens perform a dramatic recreation of the Makkos for us. At Chad Gadya, we all make sound effects and mimic Ta for dizabin Abba. It’s like the best Sedarim of my childhood, and I begin to remember how much I like my family most of the time.

And then, while Tali and Aliza and I are cleaning up, energized and a little delirious from lack of sleep, there’s a padding of feet on the stairs and Rus emerging, squinting at us. “Sorry, guys, can you keep it down? It’s two o’clock in the morning.”

Tali makes a face, a little yikes! as an apology.

I say, rounding off my edges like I always do, “Yeah, but while you’re up anyway, can you get Nachi to bed? He took forever last night.”

Rus blinks at me. “You’re the one who put Nachi to sleep last night?” There is no thank-you, no apology, only Rus yawning and saying, “He really can’t be on a top bunk. He gets vertigo.”

“Feel free to do it yourself next time.” I shrug and ignore Tali’s elbow.

“I would have. But I wasn’t feeling well. It’s not like I have someone else to help me when I need it,” Rus says, her face tightening. “Nachi could have taken care of himself. He’s five. He puts himself to bed all the time. You don’t need to be so—” She stops.

“So what?” I demand. “So considerate? Because let me tell you, he would have been up all night if I hadn’t gotten him into a bed. And then no one would have slept except for you.”

Aliza grimaces. Tali says, “Malky, calm down—”

“I am calm,” I say through gritted teeth. “I’m just making a point.”

“She gets it. She doesn’t need you to beat the point to death,” Tali retorts. “You don’t need to make her feel worse about this—”

“You don’t need to speak for her!” I snap back. “She’s an adult! She doesn’t need a lawyer!”

“Malky!” It’s Ma, emerging from another room. She looks disapproving. “That’s enough.”

I throw up my hands. “Fine. Whatever. I’m going to bed.” Let Tali finish by herself. Let all of them watch me with those tired, disappointed eyes. Malky’s at it again. When is Malky going to grow up?

And for Rus, there will only be sympathy.

That’s how it’s always been. It isn’t going to change, and I am a child again, railing at the impossible. Fighting against something immovable, throwing myself at a skyscraper as though I might be able to knock it down. There is no scenario here where I win, where I get the validation I deserve. Where someone tries to see it my way.

I can’t go to my room, to admit to Shmuli that I couldn’t keep my cool. He’s so much more relaxed than I am, and he won’t understand how Rus sets me off, how every fight leaves me defeated. He won’t understand why I can’t shake it off.

Instead, I go outside and sit on the steps. I can do this. One more day and it’s Chol Hamoed. I can find excuses to evade family trips. One more day and—

“He wouldn’t have been up all night,” Rus says from behind me, because of course she can’t let an argument go. “I know how he operates. I’m his mother.”

“Yeah? You watch him at home like you watch him here?” I can’t help myself, can’t stop the belligerence from sneaking into my voice. There’s no one here to stop me with meaningful looks and sighs. There’s only Rus, her eyes flashing as she huddles deeper into her robe, her face white in the moonlight.

Rus rolls her eyes. “You know, you don’t have to criticize everything I do.”

Someone should. I can feel the muscles of my arms tensing, the way I feel so rigid and furious at once that I have to stand, to take a few steps back onto the lawn. “You’re one to talk. Every time I try to do something nice for you, you turn it into a thing. Nachi gets vertigo. Shabsi doesn’t need more candy. It’s always like this with you!” I twist around, see my new car, and feel the rage rise even sharper than before. “You take and you take and then you do nothing but complain—”

“Well, I’m sorry I feel comfortable enough with my family to be honest,” Rus says, pressing her lips tightly together. “I spend the rest of the year trying to make the best of things. Pretending I’m healthy so the kids don’t get scared. Pretending I’m happy living across the country from home because of a custody agreement. Pretending I’m doing just fine so people don’t start treating my kids like they’re dysfunctional chesed cases — I’m so sorry I can’t measure up to your perfect life, with your perfect husband and perfect children—”

“You don’t know a thing about my life. You never did. You’re so busy in your own misery you never considered that I might have— that anyone else might be suffering.” I jab a finger at the car, and I almost….

I almost say it right then, almost talk about how it feels to never have enough, to see my kids disappointed over what we don’t have. Faigy running her fingers over a new dress while I rush her to the clearance rack. Baila begging for the new tchotchke all the other first-graders have. Shrugging off Shua’s upsheren to my friends, oh, it’s not a big deal, when I’d really wanted to have something exciting for my little boy. To talk about all the things Rus has taken from me.

To talk about how it feels to never be enough, to be faced with disapproval and a reminder that I have value in my home only if I am giving of myself to my sister. To talk about years of growing up in a home where my feelings were never a priority—

“Grow up,” Rus says.

I stare at her, aghast at her brazenness. Rus is framed against the light of the picture window of the dining room, a silhouette in black. “Grow up,” Rus says again. “Isn’t it past time you got over the fact that… that…” She laughs, rough and angry. “How much longer are you going to hold it against me that I was a kid who needed more than you did?”

And she turns and strides into the house, leaving me alone with the rage still swimming through me.

I walk away. Lean against a wall of the house, stare up at the stars, feel nothing but rising defeat. What’s the use in being angry about this? What more can I do?

Grow up.

Am I the villain here? Rus is… objectively, she’s the one who’s really struggling. She’s always sick. Her pregnancies had been complicated, and then there was her divorce. She lives far away from her family, and she isn’t super social, either, doesn’t have the friends and support someone else might get.

No, I tell myself forcefully. Rus is having a hard time, yes. And I do give. I look after her kids even when I’m not asked. I paste on a smile and pretend not to hear most of her snide comments. I didn’t tell her about the car.

But there has to be a limit. Somewhere, somehow, there has to be a line. Can’t I expect some respect? Some kindness? “Can’t I stand up for myself?” I ask the cool darkness.

My car doesn’t respond.

Another question drifts to me, an unpleasant one. Is it worth it?

The resentment over the car is like a suffocating weight, hanging over my every interaction with Rus. The frustrations over our childhood are killing Pesach, not for the first time. Is it worth it to hold on to all of this, to try to fight a war I’ll never win?

Is it worth it to let Rus destroy even more of what I have, tearing apart my relationships and my Yom Tov like she used to tear apart my books and dolls?

Rus isn’t going to change. I’m not going to change her by pushing her, by demanding thoughtfulness and apologies.

There’s really only one person I can change.

I

give the kids breakfast in the morning, Lebens splattering the kitchen table and walls. It’s fine. I wipe them down, encouraging a loud rendition of Dayeinu.

When the others come downstairs and see me, I spot the wariness on their faces, the uncertainty. News of my outburst has flitted from room to room, apparently. Everyone is waiting for me to explode.

I don’t explode. Through sheer force of will, I keep a smile on my face, and I ignore Tali and Ma when they try to talk to me about last night. Rus says something about the Leben, dairy gives Uri a stomachache, and I feel the familiar tension in my muscles, the desire to snap at her.

I say, “Oh, I didn’t know,” as casually as I can manage. Rus doesn’t respond.

And it’s… okay. It’s agonizing, and I almost want to scream when Ma puts a hand on my arm and murmurs, “I’m proud of you,” like I’ve mastered some great challenge and learned to join the Official Rus Fan Club. But it’s a performance, and now I’ve committed to it.

“What’s your game?” Tali asks when we’re alone, hands on her hips. “You’re not going to tell her about the car, are you?”

I roll my eyes. “Come on, Tali. We’re all adults here.”

Tali doesn’t look convinced, but she steps away and leaves me to play Rummikub with some of the cousins.

It’s harder to change around family than anyone else. Family doesn’t let you do it quietly, without explanations or justifications. Family never forgets who you once were, and they never let you forget it, either. Even sitting next to Rus at the table becomes a cause for alarm, for narrowed eyes and wary comments.

Rus doesn’t say anything. She just talks about the food, how Uri loves the chicken. I break down the recipe for her. Slowly, gradually, the table relaxes.

Maybe it’s just that we’ve fought so many times there’s no use in bearing the arguments overnight. No resolution, no closure. That’s how we do it. Battle, ceasefire. Battle, ceasefire. No peace.

But Rus is also a pro at pretending, I remember from last night, because by the afternoon, we’re sitting together outside, yawning and watching the kids play. I’ve brought my magazine and she’s brought her book, of course, because we don’t casually schmooze, but conversation happens gradually. “Nachi’s having a rough time in school,” she confides.

I nod knowingly. “He’s been getting in trouble?”

“He’s an angel,” she corrects me. “Quiet, well-behaved….”

“No way.” Right now, he’s sitting atop the monkey bars, shrieking and throwing catkins at the other kids.

“I promise! He gets it all out at home. But he’s so much like me in school. Shy, quiet… I worry he doesn’t have friends.”

“I had that with Baila in nursery,” I remember. “It helps to arrange the playdates at this age, even with kids he doesn’t know well. You never know who he might click with. I would ask the morah for recommendations.”

Nachi kicks Faigy in the head. Rus doesn’t move, doesn’t reprove him, and I can only be so tolerant when it’s my daughter who’s getting the brunt of it.

“Rus. Nachi just kicked Faigy.”

Rus stares at me, and I can see the defensiveness rising in her eyes, the need to explain away Nachi’s misbehavior. I force myself to stay silent, to wait. To do something other than snap at her right away for being so callous.

She turns away from me. “Nachi! Down,” she orders.

It’s something. It’s a start.

T

ali, Rus, and I take the kids on a “hike” on Tuesday that’s just a walk through the woods to a stream. The kids kick off their sneakers and wade in a small stream we find, turning their nice Chol Hamoed clothes filthy, but they’re having the time of their lives.

Tali parks herself on a high rock, and I’m with Rus again, sitting together, splashing the kids and dipping our toes in. The water is cool, refreshing, and Rus’s eyes sparkle. “I’m going in,” she announces.

“You are not. You have no idea what’s in the water — you’ll be filthy—”

“Are you afraid, Malky?” Rus takes off her shoes and steps out into the center of the stream. “What’s the worst that can happen?” Her eyes dance, light with energy and playfulness like I’ve never seen them before, and for a moment, I really do understand why Tali and Ma seem to like her so much.

Then she splashes me, and I let out a cry of outrage. I was right! She’s the worst.

I stalk down into the water and find a hunk of disgusting weeds to hurl at her shirt. “Malky!” Tali shouts. But it’s kind of therapeutic. Why didn’t we go on more of these nature-type hikes when we were kids?

Rus dances away from me, and we’re laughing, kicking water at each other until the kids join in and Tali is rolling her eyes at all of us, deeming us too disgusting to go into the house. Instead, she turns on the sprinkler system when we get back, soaking the kids until they’re clean.

I’m feeling like I’m ten again, but for the first time, it doesn’t awaken resentment and despair in me.

Ma is there when I hurry inside to shower, and she frowns at me. “I heard you had an altercation with Rus in the water,” she says, because of course that’s the first thing that Tali had reported when she’d come in. “Don’t you think that you could give her a break? She’s had a rough year, and this is really her only time to spend with family.”

It dampens my mood, though I should have expected it. Ma’s eyes are shining with empathy, as though we’re both on the same page when it comes to Rus. “We were… we were just playing around. You can ask Rus,” I add, though I can’t imagine that Rus is really capable of passing up a chance to let me suffer for our sins.

That’s not fair. She’s been trying, too.

It’s just hard to remember it under Ma’s sorrowful gaze.

WE

do one more trip on Wednesday, to an amusement park where I go on roller coasters with the older kids until I’m green. Rus offers me a bar of chocolate “for my service,” and I eat it and sit on the side for the rest of the trip, breathing slowly.

It’s nice. Chol Hamoed with Rus has actually been nice. And maybe it’s just me, but Rus’s snide comments have been lessening, have been a little more considerate. Maybe I’m becoming more tolerant. Maybe she’s getting a little less defensive.

Whatever it is, we cook together on Thursday while Ma takes the kids out, and it’s not bad. I work on a corned beef while Rus examines a spaghetti squash. “Why is it bigger than my head? Like, who’s going to eat that much spaghetti squash? I eat spaghetti squash on a regular basis, and this would take me a month, at least.”

“There are a lot of kids here,” I point out. “At least… two of them might try it.”

“It’s all up to us,” Rus says grimly. “You and me, taking on this spaghetti squash. Two days. Four meals. No cheese.”

“No cheese makes it impossible!” I protest.

“Think we can talk Ta into a milchig meal?”

“What if we do it subtly?” I eye the salmon on the counter. “Like, we do a mushroom soup. Then serve fish. Then serve a bunch of sides. And before you know it, the meal is oddly pareve, and hey, has anyone thought about melting enough cheese on the spaghetti squash that it’s edible?”

Rus laughs so hard that she drops the spaghetti squash.

We scoop out its remains and debate over the sauce, and then I make another batch of almond flour cookies. “I know they’ll be awful after Pesach,” Rus sighs. “But somehow, I keep telling myself I’m going to love them just as much then.”

“Is it really so different being gluten-free on Pesach and during the year?”

Rus shakes her head. “I can’t eat rice now. Do you have any idea how hard that is?” She eats a cookie as Tali wanders in, drawn by the aroma.

“No one here can eat rice now. You’re not special.”

“Malky!” Tali elbows me. Her glare is warning, and she says reprovingly, “Be nice.”

It’s alarming, how quickly my mood shifts, how I can go from having a good time to feeling sour and resentful toward Rus. I was joking, I want to say. We’re getting along for once.

But Tali won’t see it. Tali is forever on Protect Rus Mode, and I’m always going to be the bad guy, the one who’s out to get Rus.

I want to snap at both of them, to say something snide about being nice when I’m the one who’s been in the kitchen all day. When it’s my cookies they’re eating, the cookies Rus had been so snobbish about before Pesach. If Tali is so worried about me being around Rus, then the two of them can go cook together and leave me—

“Sephardim are special,” Rus says, ignoring Tali’s comment. “I’m telling the shadchanim I will only date Sephardim from here on out. For these eight days? It’s worth it.”

And a look passes between us, an understanding Tali misses entirely while she’s watching me warily. A realization, really, that’s been building between us for days.

Our family still sees two children squabbling, a fragile little girl who must be protected from her strong-willed sister. A girl who must take because she has so little, and the girl who must give to her because she has so much. Our family will never see anything else.

It doesn’t mean it’s what we have to be.

R

us doesn’t get to fixing Faigy’s robe after Pesach. Of course not. She’s not driving all the way into the city for that. The original plan had been for most of us to clear out Motzaei Pesach, even though we have the house for a couple of extra days, but the kids beg for one more day to swim and explore while we pack up the house, and I agree.

I run to town for some chometz. Rus eats Pesach leftovers and the rest of us have pizza on the patio. The cousins are best friends by now, Faigy and Nachi glued together, and they beg to have another visit sooner than next year. “Maybe we’ll try video chats,” I suggest.

“We never do video chats with Faigy,” Nachi says accusingly.

Rus and I glance at each other. “Well, we’ll have to start,” Rus offers.

Ma is scheduled to take Rus to the airport, but there’s an emergency at work, she has to go in, and there’s no choice but for me to do the drive.

“Are you sure you two will be okay?” Ma asks me quietly before I leave, her eyes darting from Rus to me. There’s still time to ruin Rus’s trip is implied in the question.

“I won’t talk about the car,” I say, my forever mantra, and Ma sighs as though a load has been rolled from her shoulders.

I don’t think I’ll ever change Ma’s impression of me. But it doesn’t have to ruin the ride, I decide, and I find my smile again once we’re out of the house.

“I really appreciate it,” Rus says when we turn into the airport. “This has been… it hasn’t been that bad, you know?”

She hasn’t commented on my new minivan beyond a wince when we went over a pothole. I’ve been waiting for it, kind of. I don’t know what I’ll say. Telling her about the car had held a certain kind of spiteful satisfaction for so long, but right now, it feels like it’ll just upend something good.

“It’s been tolerable. You’ve been tolerable,” I tease. The edges of my words aren’t rounded anymore, are a little jagged, but Rus handles the scratch just fine. “I’m almost not dreading next Pesach.”

“Give it time.” Rus leans back in her seat. “Another flight with the boys should be just enough to remind me that I never want to get on a plane again.”

“Good luck.” I find a spot near departures and pull in.

Rus hesitates. “There’s something else,” she says. She bites her lip, a little rueful. “I’ve been… I kind of pushed this off, I guess. No one was talking about it, and I didn’t want it to ruin Pesach.” She fishes through her bag and emerges with an unmarked white envelope.

I take it, bewildered. “What is this?”

There’s a check inside, made out to me, dated several weeks ago. Fifteen thousand dollars.

“That’s how much Aliza thought it was, anyway. She wasn’t sure. Moshe said that Ta wasn’t that forthcoming about the whole thing.” Rus bites her lip. “Aliza was surprised I hadn’t heard about it from you or Ma.”

I stare at the check. Then at Rus. “You knew about the car.”

Rus bobs her head. In the back, the kids are starting to get restless, and Rus talks quickly. “I’m not, like… I have some money. I have a good job, and Aharon is decent with his child support payments. I’m not some destitute single mother. And it was my fault, wasn’t it? I should pay for the car.”

My fingers shake. I don’t know what to think. It’s dated before we worked things out, before we began to find some resolution. It’s going to change everything for me, to make things a little easier for the next year—

“I can’t accept…” I say automatically.

“Take it. It’s yours,” Rus says sharply. “I spoke to my rav. I know what I did.”

And all I can think is to say, “Ma will be furious if she finds out.”

“It’s not Ma’s business,” Rus says fiercely. “We don’t need everyone else standing over us, telling us how to feel or what to think. I love our family, but we’re adults. We can be… this can just be us, okay?”

She doesn’t wait for an answer. “Nachi, Uri, Shabsi, let’s get going. Who’s going to pull the wheelie?” She pushes the door open, slips out of the car and goes around to the trunk. In moments, my car is empty, and I am still frozen, sitting at the wheel with a check in my shaking hands.

Rus and I, we don’t apologize. We don’t find closure when we fight. We don’t hash out our differences and negotiate peace on the battlefield. But there is a paper in my hand, light as a white flag, and I have already waved my own.

“Okay,” I whisper. Ff

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 939)

Oops! We could not locate your form.