A Fight or Flight Response

| January 14, 2025Emotional eating isn’t about lack of discipline; it’s often a nervous system response

A Fight or Flight Response

Shira Savit

For many of us, emotional eating is a constant struggle. We reach for snacks late at night or when we’re stressed, only to criticize ourselves afterward: Why can’t I just have more self-control?

But emotional eating isn’t about lack of discipline; it’s often a nervous system response. With stress, our body shifts us into survival states — fight, flight, freeze, or please. These responses, designed to protect us in moments of perceived threat, profoundly impact the way we eat. Understanding these states and the patterns they create can help us move away from blame.

Fight Mode: Eating to Release Tension

The fight response is all about confronting a perceived threat. In this state, eating can become hurried and intense. Imagine a mother rushing to get her kids out the door in the morning. The toddler is crying, the seven-year-old can’t find her shoes, and the car pool is honking. Frustrated, she snaps at everyone to hurry up. When the house finally quiets, she stands in the pantry and grabs a handful of corn chips. The act of eating becomes a way to discharge the tension and regain some sense of control. In fight mode, you might find yourself drawn to crunchy, spicy, or bold foods that match the heightened energy of your emotions. Triggers for this response often include conflict, feeling unappreciated, or managing chaos in your environment.

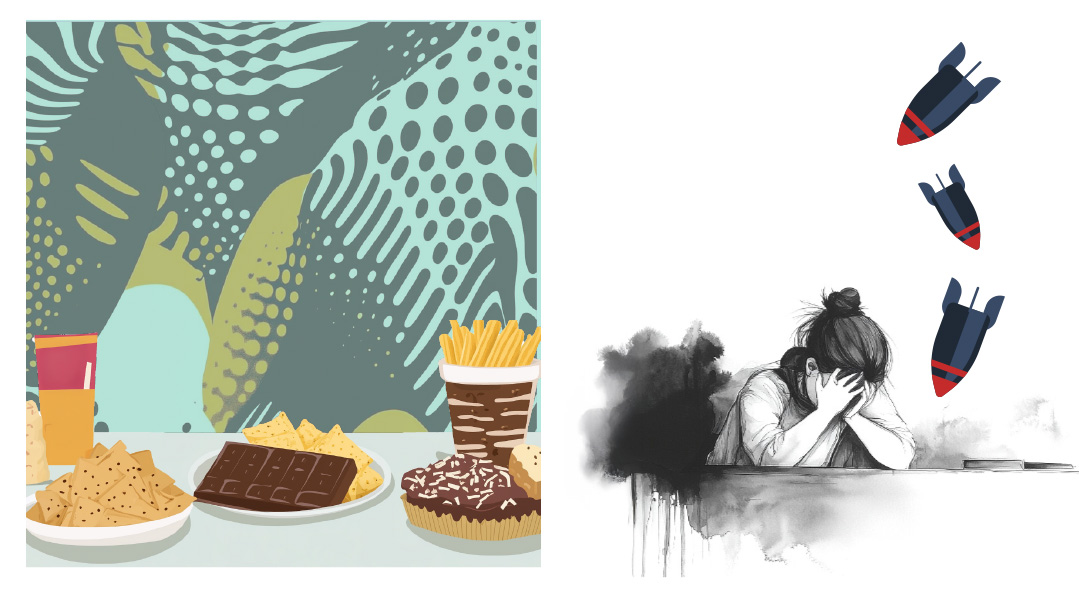

Flight Mode: Escaping Through Food

Flight mode kicks in when your nervous system perceives stress and prompts you to escape the situation. Eating in this state often serves as a way to numb the discomfort. For example, a mother receives a call from her child’s teacher about his misbehavior. Shame and anxiety build within the mom, and after hanging up, she wants to detach from the overwhelming emotions. She goes to the kitchen and grabs a chocolate bar. The creamy sweetness offers a brief sense of comfort, allowing her to escape from the heaviness of the moment. In flight mode, food often becomes a tool for avoidance, with cravings for sugary, indulgent, or fast-to-access options, which provide an emotional retreat from the stress.

Freeze Mode: Eating on Autopilot

Freeze mode is marked by a sense of being stuck or immobilized, unable to act. This often happens in situations that feel too overwhelming to process, like facing a major life decision or receiving bad news. In this state, eating can become robotic and disconnected. You might find yourself on the computer, eating pretzels and barely tasting them, as deciding what to do next feels impossible. Freeze mode often leads to cravings for low-effort foods — packaged snacks, takeout, whatever is easiest to access — and is triggered by feelings of being stuck in transitions, stressors, or uncertainty.

Please Mode: Neglecting Your Needs

The please response arises when we prioritize others’ needs above our own to maintain harmony. For example, after spending the day preparing for Shabbos, you barely pause to sit down. Once the guests leave, you find yourself nibbling on leftover kugel or dessert, as your body is seeking care and nourishment. In this state, people often reach for foods tied to connection and approval, like baked goods or comfort foods. Triggers for this response include social pressure and the need to meet others’ expectations, often at the expense of your own needs.

The first step in addressing emotional eating isn’t about changing the food — it’s about understanding your body. It can be helpful to notice your state before and during eating. Are you feeling angry (fight), anxious (flight), stuck (freeze), or overly focused on pleasing others (please)? As you build this awareness, try to validate your experience: It makes sense that I’m craving this right now. My body is in a survival response.

Once you’ve identified your state, somatic regulation tools can help you shift out of survival mode. Techniques like grounding, orienting, or deep breathing can regulate your nervous system. These tools are often most effective when learned with the guidance of someone trained in somatic work.

Over time, compassionate awareness of your body’s responses can guide you to make small, meaningful shifts — one moment of understanding at a time.

Shira Savit, MA, MHC, INHC is a mental health counselor and integrative nutritionist who specializes in emotional eating, binge eating, and somatic nutrition. Shira works both virtually and in person in Jerusalem.

All in the Interpretation

Shoshana Schwartz

H

ow can a siren not be scary? A few weeks ago, I was resting comfortably when I heard a siren go off. I didn’t rush to the bomb shelter. My heart didn’t race, and I didn’t think, “Who’s home? Where’s everybody?”

Instead, I paused, took a breath, and then it was business as usual, followed by feeling gratitude — because I knew this siren was only a test.

Normally, a blaring siren triggers a stress response. But this time, my nervous system stayed calm. Why? Because a program in my mind was already running: “This is just a test. You’re okay.”

We often assume our feelings are dictated by what happens to us, but in reality, they’re shaped by the meaning we assign to those events. And those meanings are shaped by our past experiences.

Reflecting on key moments — like a childhood memory or significant event — can help us gently uncover where those beliefs came from and question if they’re still true. And while we can’t control our first thought or instinctive reaction, we can learn to pause and dig deeper. When a strong emotion arises, we can ask ourselves, “What belief is fueling this feeling?” This simple question opens the door to clarity and transformation.

Simply put, it’s not the event itself that creates fear, joy, anxiety, shame, or connection. It’s our interpretation of the event. Each time we practice challenging those interpretations, we open ourselves to outcomes like greater emotional freedom, reduced stress, or stronger resilience.

Through gentle techniques like EFT Tapping (Emotional Freedom Techniques) or IFS (Internal Family Systems), we can revisit pivotal moments, helping our inner child feel prepared for what’s about to happen. We can’t change the past, but we can steadily shift how we interpret and respond to it in the present —much like hearing a siren and knowing: “I’m safe.”

Shoshana Schwartz specializes in compulsive eating, codependency, and addictive behaviors. She is the founder of The Satisfied Self.

Overlooking to Understanding

Hadassah Eventsur

Many late-diagnosed neurodivergent women share the experience of being diagnosed with depression or anxiety before they were diagnosed with ADHD. In these cases, some of the therapeutic interventions designed to overcome or “cure” the symptoms of depression and anxiety seemed to exacerbate them. For example, if you have ADHD, exposure therapy may overwhelm your sensory system. Motivational affirmations will not help your time-management skills. Cognitive behavioral interventions will not improve your ability to hold bits of information in your working memory. So if you find that therapy is exacerbating your symptoms of anxiety or depression, you may want to explore a possible ADHD diagnosis.

Hadassah Eventsur, MS, OTR/L is an occupational therapist and a certified life coach. She is the founder of MindfullyYou, a program that supports frum women who struggle with executive functioning.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 927)

Oops! We could not locate your form.