The Finnish False Messiah

| December 24, 2024It was only natural that following the Holocaust...messianic yearnings would once again surface

Title: The Finnish False Messiah

Location: Paris, France

Document: The Jewish Frontier

Time: 1951

Numerous false messiahs have cropped up throughout history. Some, like the Christian messiah, Shabtai Zvi, and Jacob Frank, had a significant and often damaging impact; others made for curious historical footnotes rather than causing widespread upheaval. Jewish hope for the final redemption became especially acute following times of crisis.

The Roman persecution in the second century fanned hopes for the ultimately failed messiah of Shimon Bar Kochva. Following the expulsion from Spain and Portugal at the end of the 15th century, David Hareuveni and Shlomo Molcho turned up on the scene promising redemption. And in the wake of the desolation of the 1648-49 Chmielnicki massacres, the infamous Shabtai Zvi wreaked havoc on the Jewish world desperate for a better future.

It was only natural that following the Holocaust, the greatest destruction in Jewish history, messianic yearnings would once again surface. Many survivors described liberation as a moment of mixed emotion, after they had fantasized through the years of horror that the end of the war would bring the arrival of Mashiach.

A prominent chassidic survivor from Hungary named Reb Chaim Alter Roth submitted this testimony:

The entire time in the camps, a desperate hope pulsated within us, that immediately tomorrow the Geulah would arrive. My father would often wistfully remark, “Mashiach Tzidkeinu will come to Auschwitz.” We thought that with that revelation, all would instantly become clear with the Geulah. We would clearly see and understand why we had suffered so much, and we would finally gain an insight into the purpose of all of our misery and pain.

But it was even more difficult when the day of liberation came. It was referred to as “liberation,” but I’m not sure why. Instead of experiencing redemption, we instead internalized the total destruction all around us. The world continued on its usual course, nothing had changed, the hester panim continued on as before….

That tangible sense of disappointment was fertile ground for messianic tension. Though there’s much to expound on the diverse postwar reactions to the stirrings of redemption, it’s worth focusing on a more obscure and rather bizarre expression of a false messiah who appeared on the Jewish scene very briefly and rather quietly.

IN 1945, while residing in Paris as the editor of the Yiddish newspaper Unser Vort, Yiddish journalist Mordechai Shtrigler became aware of a curious figure. One Shabbos afternoon, Shtrigler was invited to deliver a lecture on the topic of false messiahs throughout history. In the front row of the audience sat an elegantly dressed Jewish man, accompanied by a sad-looking and clearly physically unwell woman. Shtrigler noticed that the man’s eyes occasionally flashed with anger at what he said.

After the speech, the man approached Shtrigler and launched into an attack on his lecture:

So you wanted to prove that all those who claimed to be messiahs were liars or deluded persons? Eh? Reason dictates such a conclusion, you say. Maybe you don’t believe that a true Messiah will ever come at all.

Well, I want to ask you something. See this girl? This is my sister. The Germans robbed her of her parents, her sisters, her bridegroom. All of them are dead. She hid in a damp basement for years, and now she is crippled. Maybe you know why this is so? I tell you, they were all innocent victims. What? You know it. Well, then, will it remain this way forever? Will this wrong never be made right?

I tell you it will be made right. One must come — yes, the Messiah — who will make all things right. Otherwise the world has no right to go on for even half a minute. I must get back my innocently murdered parents and she, my sister, must get back her groom, just as he was before. This is how it will be. The Messiah will make everything right again. Nothing that was in the past will be missing. Only He can give meaning to the world.

Shtrigler now understood the circumstances (or he thought he did) and began to pity the poor woman. Even as a survivor himself of Majdanek and Buchenwald, there was little he could say or do that would help console her. Her tragic plight had just one solution — the coming of Mashiach — and because of her fragile state, she had seen his lecture on the fraudulent messiahs in history as getting in the way of her ironclad beliefs.

Shtrigler goes on to describe the sad sight:

Tears flooded the sick girl’s eyes, and because of them, it became pointless to answer the man.

Anything I might have said in reply would have been a dagger aimed at the heart of the girl’s hopes. What she needed was a detailed description of the Messiah’s appearance, how he would restore color to her face and straighten her deformed shoulder. She needed to hear how a mighty hand would restore the life of her groom from the scattered ashes and bring him back to her, whole and alive.

Suddenly, the entire conversation changed as her brother leaned over to Shtrigler and whispered: “He [the Messiah] has already arrived. I even know where he is. You want to know where? He is in Finland now, in Finland.”

Sometime later, Shtrigler received a pamphlet titled, “My Annunciation of the Complete Redemption and Concerning the Coming of the Messiah of G-d,” authored by the self-proclaimed Messiah from Finland, whose name was given as Ze’ev Mordecai (Ulf) Karmi (1912–1969). The pamphlet contained writing that was strange and clumsy, but showed sparks of intelligence.

Shtrigler later discovered that Karmi (born Kantarowitz) was presenting himself as a pious young rabbi, and had been invited by the French government to catalog biblical literature at the Sorbonne. He began sending out bulletins hinting at his divine mission. His disciples spread tales of his miraculous powers — how famous scientists left his presence astonished, how people fell into trances upon seeing him and shouted that they saw G-d on earth, how he cured a dying man with a touch and a word.

Shtrigler’s curiosity was piqued. When one of Karmi’s followers called to ask if he’d like to meet the Messiah, Shtrigler agreed, though the meeting could only take place once Karmi had examined Shtrigler’s soul from afar to determine if he was deserving. Finally, a note arrived in Karmi’s own hand agreeing to an audience.

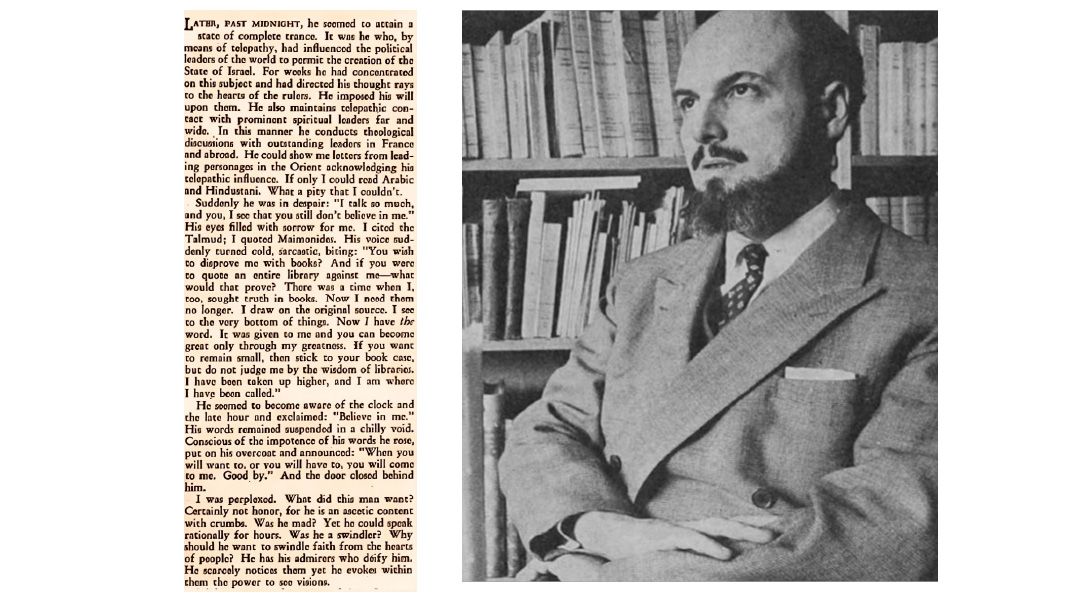

In a darkened private apartment, Karmi made his entrance — a tall man dressed in neat black rabbinical garb, with a carefully trimmed beard framing his pale face. He sat in profound silence.

After some coaxing, Karmi began to share his story:

He was born in Finland. There, he managed to study Hebrew, and as he grew up, he was overcome with the urge to study the Torah. So he went to the yeshivah of Telz, and then to the one in Mir.

That was in the 1920s. He studied much. He probed the morality [mussar] books. He was ordained a rabbi. He mentioned the names of some of the outstanding rabbinical scholars of that time whom he had met personally because the fame of his piety had gotten around, and there was curiosity to see a yeshivah student from remote Finland.

Later, he studied in the universities of Helsinki, Stockholm, and Copenhagen. He obtained a number of doctorate degrees. He studied several subjects simultaneously. There was no satiating his hunger for knowledge.

Then the war broke out. He was a citizen of Finland. His brother was a high-ranking officer in the Finnish army. It was a comical situation, during World War II, when German soldiers fighting on the Finnish front had to take orders from Karmi’s brother, the Jew. Hitlerites had to salute him.

Oh, that was something to see.

He must have noticed on my face an expression of distaste for the humor of the situation.

He hastened to explain. What could the few hundred Jewish soldiers do? They were citizens of Finland, a country that had never known discrimination or anti-Semitism. Even when German units were stationed in the country, the Finnish government did not permit them to show their hatred in any way. Karmi served as a chaplain in the Finnish army. Yes, it was a satisfaction to have German soldiers salute Jewish officers, helpless in their rage. There was healing in such a sight. What? I did not agree?

Well, I should have seen it with my own eyes.

Though, of course, there was another side to the picture — the stories of Nazi atrocities in other countries and the impotence to do anything about them.

Karmi’s brother, the officer, was killed in battle. After the war, Karmi took a post as a Hebrew teacher in Finland. His salary was fair, and he could have organized his life very satisfactorily indeed.

What was he lacking in prosperous Finland?

Nothing at all. He enjoyed the respect of all his acquaintances and even commenced work on a great book. He could have lived so peacefully that there would have been no story to tell. And then something happened.

After the war, while working as a Hebrew teacher in Finland, Karmi said that G-d had appeared to him and given him a divine mission, but he would need “thousands of young prophets also capable of seeing G-d” to fulfill it. He taught prophecy to his students, Christian and Jewish, and claimed that some attained direct revelations. But this led to his persecution and exile, first to Denmark and Sweden, then to France.

In France, Karmi said, G-d appeared to him and instructed him to set up a school of prophecy and convert the world to the true faith only he understood. Biblical figures visited him (as well as the so-called prophets of other religions). He claimed to have influenced world leaders telepathically to allow for the creation of the State of Israel. He offered to make Shtrigler a prophet too, if only he would believe in him.

When Shtrigler tried to counter Karmi’s assertions with basic Talmudic and rabbinic sources, Karmi dismissed them, saying, “There was a time when I, too, sought truth in books. Now I need them no longer. I draw on the original source. I see to the very bottom of things.”

He departed abruptly, leaving Shtrigler perplexed.

Shtrigler walked away from the meeting confused. He realized that Karmi was an intelligent man, but clearly suffered from a mental illness. But his motivations eluded the author. He seemed to crave neither wealth nor honor. Under normal conditions, Shtrigler mused, what might such a man have accomplished? Earlier, Shtrigler had suggested Karmi go to Israel, where he could be useful; Karmi replied “I am there whenever I have to be there, whenever I want to be there.”

Shtrigler concluded that here was a soul who had simply lost its way, a tragedy not just for Karmi but for the entire Jewish People, following the great tragedy of the Holocaust. Lost souls, post trauma, and messianic yearnings, were all woven together during this challenging time of rehabilitation.

Finnish Jews in the Fuhrer’s Forces

The Jewish community in Finland traces its origins to when the country was incorporated into the Czarist Russian Empire. Jewish veterans of the Czarist military, such as Cantonists from the time of Czar Nicholas I, were permitted to reside outside the Pale of Settlement following their departure from the military. Some of these former Russian Jewish soldiers settled in Finland and established a Jewish community there.

At least two shuls were constructed, and Rav Yisrael Salanter’s close student Rav Naftali Amsterdam even served as rabbi of this unique community for a time. During World War II, Finland was an ally of Nazi Germany in the war against the Soviet Union. But Finland didn’t strip its Jews of any rights, and a few hundred Jews served in the Finnish military during the war, some even as officers.

These were the only Jews during World War II who served on the side of the Nazis. It was an incredibly ironic situation, in which Finnish Jews were proudly serving their country to regain territory taken by the Soviet Union, yet they were serving side by side with the German army that was carrying out the Final Solution in Europe. Perhaps the greatest historical irony of all was that these Finnish Jewish soldiers were descendants of Jewish soldiers who had been drafted into the Czarist military a century earlier.

Divine Delusions in the City of Gold

The ancient stones and spiritual intensity of Yerushalayim have long drawn seekers of meaning and transcendence. For a rare few, this sanctity overwhelms, leading to Jerusalem syndrome — a psychological phenomenon with visitors who, swept up in the city’s holiness, believe they are on divine missions. Clad in flowing robes and quoting scripture, they wander the Old City imagining themselves as prophets or biblical figures.

Most cases are brief, lasting no more than a week, though some reveal deeper mental health struggles. Between 1980 and 1993, Jerusalem’s Kfar Shaul Mental Health Center treated about 1,200 such visitors.

“If you’re in L.A. and you think you’re Napoleon, you don’t have a burning desire to go to Paris and start a war,” explained Dr. Yair Barel, an expert on the syndrome. “But if you’re in L.A. and you think you’re the Messiah, you definitely have a need to come to Jerusalem.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1042)

Oops! We could not locate your form.