20 questions for rachael lavon

| September 29, 2024“Considering every possible experience I’ve ever had lives somewhere in my subconscious, I usually manage to dig something up”

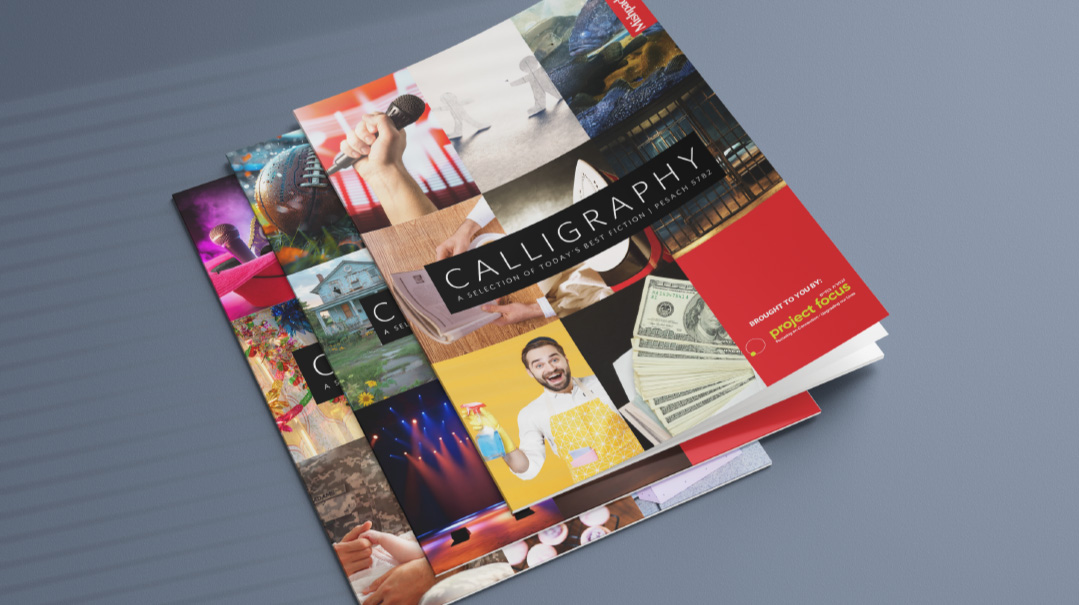

Rachael Lavon is an award-winning writer who serves as the editor of Calligraphy, Mishpacha’s semiannual literary collection. Rachael has a passion for writing short fiction, essays, and articles about various topics, and enjoys coaching aspiring writers in the art of fiction.

My ideal environment

Stick me in a place with no opportunities for procrastination and it’s like magic. I once wrote an entire Calligraphy story while waiting for my car at the mechanic.

Deadlines make me

produce. But also incredibly stressed out.

I learned the most from writing about

medical mysteries.

The professional accomplishment I’m proudest of

the stories that made it to school curriculums. It’s kind of mixed emotions though, I’m not sure how I feel about my story being some poor sixth- grader’s dreaded homework.

The best piece of advice I got was from

Avigail Sharer, who taught us that the conflict of any fiction story should be there within the first sentence of the story. I tell my writers that if they’re finding it hard to hint at the conflict within the first sentence, they don’t have a real handle on the main conflict. Stop writing and figure it out before you continue.

1

Do you remember the first story you wrote?

It was a story entitled “Underwater,” about two girls who witnessed a drowning and the guilt they carried for not trying to save the third party. The original draft was saved from the rejection pile at Family First by the wonderful editors Bassi Gruen and Avigail Sharer. They offered me the chance to work on it with them and rewrite certain parts to make it fit for publication, and of course I jumped at the offer. Basically anything I know about writing and editing I learned from them — and my grandfather Shalom Staiman a”h — who was a writer.

2

Who is the most memorable fictional character you’ve created?

I didn’t create them, but I did marry Simmy off to Laibel which seemed to make Klal Yisrael very happy. It’s nice when two people you know well marry each other. Credit where credit is due – my husband redt the shidduch.

My most enduring character is probably Lou from a short story entitled, “No Need for Knives,” who lost his arm in a car accident in the 1960s. It’s interesting how vividly people remember him. It’s also the story I worked the longest on — over ten years from when I thought it up until I wrote the first draft. With that kind of investment, I’m gratified that people remember it.

3

Where do you get your characters from?

My characters come from my imagination, which resides within the limbic system of the human body, a partnership between the hippocampus and the amygdala, according to Google.

People often ask fiction writers this question, and I find it baffling. It’s like asking, “Why is your house so messy an hour after the cleaning lady left?” — a question that has no satisfying answer.

Look, the same way you’re interviewing me to generate quasi-interesting, somewhat palatable content for this publication, I interview my own brain to generate characters, settings, conflicts, plots. Considering every possible experience I’ve ever had lives somewhere in my subconscious, I usually manage to dig something up. Does that make me sound crazy? It does, right? Please see question 10 where I describe how utterly normal I am.

4

Can you tell us about a story of yours that stirred up controversy or conversation? Why?

I’m not a very confrontational person and I’m not looking to stir up controversy. I just like writing. I know there was a lot of buzz about my story “For Posterity,” which was about a young husband who discovers videotapes of his wife’s family from before she was born in his in-laws’ basement and the fallout after witnessing his mother-in–law’s erratic behavior. The story touched on childhood trauma, mental health, and forgiveness. There was a lot of nostalgic 90s imagery that I think brought people back in time, for better or worse. It had some heavy themes.

5

Do you know how your stories will end when you start writing them?

Not always. When I do write from the resolution, my work is stronger and the writing is much easier. But it doesn’t always work out that way.

6

What is the weirdest piece of research you’ve done for a story?

I spent a tremendous amount of time researching a specific area of Montauk — a village at the end of Long Island — when I was writing my three-part Family First story, “Breathe.” I mean like hours and hours on Google Earth and street view getting a feel for what the streets looked like, the flora and fauna, the weather, the specific distance from the house I was basing the story off (an actual historical home), and the water’s edge. I’m big on research.

7

How does writing a serial differ from writing a short story? How is it the same?

Both short stories and serials tell a story, but serials require two arcs: an overarching plot with slow character growth and a mini arc in each chapter, complete with its own inciting incident, conflict, and usually some sort of resolution. Each chapter also needs to advance the larger arc, which can be tough, but the chapters are short in word count.

Short stories, while longer than a single serial chapter, have one tight arc. They can’t be novels condensed into 3,000 words. We often receive submissions that are just that — jam-packed, yet vague, lacking focus. A good short story explores a single slice of life. Mastering the pacing can be tough and it requires skill to produce a satisfying journey within a limited word count.

If a novel is a full cake, a short story is a thick, gooey slice.

I have the attention span of a fruit fly, which is why I prefer writing short stories. Serial writing feels like a big commitment, and I really admire those who tackle it.

8

Why do you love fiction?

Fiction in general or writing fiction? Fiction in general: It’s a guilt-free pleasure. You and your friends can discuss Chanie and Baruch’s dysfunctional marriage from here till tomorrow and not one bit of it is lashon hara. Writing fiction: I’m in it for the big money. It’s a passion. I’ve loved reading and writing since forever.

9

Do you ever feel that fiction is a bit of a waste of time? (Sorry!)

I never view frum fiction as a waste of time, just as I don’t see Jewish music that way. Even if you personally prefer only sifrei kodesh, the fact is that many find fiction enjoyable, and that means people will seek out reading material regardless.

In our community, where we shy away from other forms of entertainment, fiction plays a significant role. There’s a lack of secular fiction that is truly “clean” or “kosher,” and even secular children’s literature often comes with agendas most of us want to keep out of our living rooms. Therefore, anything I can do to produce more frum fiction is far from a waste of time. It’s beautiful to see such high demand for kosher reading material.

10

Do you find that involvement in fiction can lessen your grip on reality?

Interesting question! The writers I work with are generally incredibly attuned to the world around them — perhaps more than most people. To craft strong contemporary fiction, a writer must be present and aware of their surroundings. Capturing realistic dialogue, accurate settings, tone, and contemporary themes requires a person to be very tapped in and aware of societal issues and interpersonal conflicts.

People might picture fiction writers as people with flair, like someone who varies their earrings as a nod to the upcoming Yom Tov. I can assure you, the fiction writers at Mishpacha are not that — we’re alarmingly ordinary, and any internal weirdness is well hidden under thick layers of normal.

What can be difficult is the immersive writing experience, like when you’re sitting in the park watching the kids play, but really, you’re writing a scene in your head and then you need to get up and help a kid on the slide. When I first started writing professionally, I found it hard to control the On/Off switch in my brain when it came to dreaming up fiction. But it’s a muscle, it got easier over time. For the last two years I had the writing switch on Off-mode as I had a toddler home with me and no time to write. Recently he started playgroup (bless you, Morah Zippy) so I’m excited to start writing again. I’m not sure how we’ve arrived here, like, how did I veer so far away from the question? I don’t know. What I do know is that having a little one home with you for two years can lessen your grip on reality. So there’s that.

11

Can you tell us about how fiction has helped you or someone else?

Fiction can help people feel seen in a non-aggressive way. It’s different from reading an article or feature on a specific topic; fiction is much more innocuous, as its primary purpose is to entertain. Often, people find similarities between their own experiences and a character’s journey, which resonates and can be very validating. We receive letters to that effect all the time.

12

What are the top three things all fiction writers should know?

Read a lot.

Write a lot.

Repeat.

Never lean on shtick to make your story work. No cool character, cool twist, cool setting, cool time period will carry the story the way a strong plot will. If your story doesn’t work on earth it won’t work on the moon either.

That was 4. I’m terrible at math.

13

What is the hardest part of editing Calligraphy?

I get to work with incredibly talented writers who take their craft seriously, which is amazing. But it’s a big collection. Lots of words. Lots of themes, conflicts, dynamics, characters. We have to stay on top of what’s coming in so there isn’t too much overlap. It’s always hard to tell a writer that their story is gorgeous, literal perfection — but I already have seven shidduch stories and if I take another one, I’ll be fired.

14

What are the essential elements of a successful Calligraphy story?

Obviously excellent writing, a well-structured plot, realistic dialogue, good pacing, strong characters, and a solid resolution are necessary.

But most important is probably a fresh core; the main conflict of the whole story can’t feel stale. I wish I could give specific instructions on how to build a fresh cornerstone for your story, but I think this may be one of the areas where raw talent comes into play. I can’t teach it. Our writers simply have a sense of what hasn’t been done and how to capture it.

I think when people hear that we’re looking for “fresh” their mind defines the word as “different, big, exciting,” so ideas float in with stranded desert island themes, shidduch dates on Mars, or a whole lot of melodrama — and that’s the opposite of what I mean, because our target audience is (unfortunately) not eight-year-old boys. We’re not looking for big and shiny; we want stories with nuanced layers that explore the unique human experience. Go smaller, deeper, zoom way in — we want the peeling corners that haven’t been explored, gritty bits and pieces, complicated, messy emotions. We want the very realistic, very tangible crumbs under the couch. Better — we’re looking for that safek piece of chometz you didn’t find before Pesach and now have to burn after Pesach. Like, give me that Cheerio’s story. He deserves a moment in the sun before he meets a fiery demise.

If I’ve lost you, fear not. I think I’ve lost myself too.

15

How many rounds of editorial back-and-forth go into the typical Calligraphy story?

Between two and 200. I’m joking. Kind of. There’s a lot of back and forth. I’m a very annoying editor to work with, I can only assume my writers cry when they see yet another email in their inbox from me. In fact, I dread working with myself; I self-edit my pieces until exhaustion. Maybe this is why I write so infrequently? Look at me uncovering hard truths while being interviewed.

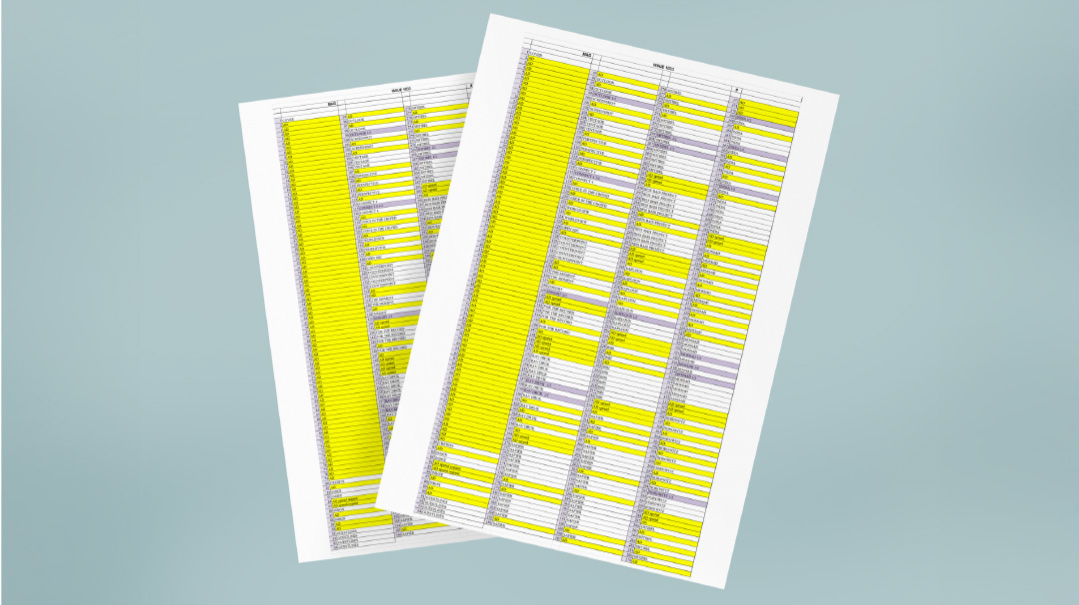

As for the process at Calligraphy, it starts with hammering out the plot with the editorial team, followed by my feedback on the first draft, second draft, and so on. It varies piece to piece and writer to writer, but once the developmental editing is complete, we move onto line editing for sentence structure and word choice, then proofreading, review by the rabbinical board, and then onto the graphics team. A lot of thought and work goes into it.

16

Do you prefer to get a Calligraphy submission in outline form, or after it’s already been written?

Officially we only accept a story for Calligraphy after reviewing the complete story. Our regular writers know they can work on an outline with me or send in pitches to hear what I think about them, but it’s hard to gauge how the final product will look until we see the whole thing written up. It’s rare that we receive a full story from a new writer that fits right into the collection without any planning beforehand, but it certainly happens occasionally, and when it does — we’re thrilled.

17

How do you balance your professional editorial expertise and the writer’s personal vision for their characters and plot?

Great question! Mutual respect is essential in this field. I really value the talent and vision of our writers, and I don’t try to fit their work into any specific mold. I appreciate their diverse styles. On the other hand, I’m thankful our writers are open to feedback when something isn’t working. They take my suggestions seriously and are willing to revise, which I appreciate.

We have a fantastic team, including Shana Friedman and Rachel Bachrach, who read through submissions and help create a balanced journal. (If it was up to me, Calligraphy would likely feature eight happily-ever-after shidduch stories.) This approach pays off; we often receive varied feedback, with different readers naming different favorites. We try to include something for everyone.

18

How do you distinguish between a story that just isn’t going to work and a story that can succeed with the right revisions?

When reviewing a submission, I’m looking for fresh themes, conflicts, and characters. If I don’t find these elements, even with beautiful language and descriptions, it’s probably not going to work.

Conversely, if I see that spark — even just one paragraph that excites me among 5,000 words of predictability — I’m often willing to collaborate with the writer to rework the story. It’s particularly important to me to invest in new writers. I’m very grateful I was given that chance when I was starting out.

19

What do you think is more important for a story’s success — characters or plot?

A successful story really needs both. Officially, Family First leans toward character-driven fiction and at Calligraphy we prefer plot-driven fiction, but the truth is one can’t work without the other. The most charming, charismatic, dynamic, tortured character still needs to be put in a situation where Stuff Happens. (Yes, that’s the official term. Stuff.) He can’t stand alone without a plot propping him up and pushing him along his journey.

And the most exciting plot will fall flat if it has no heartbeat, that perfect character to breathe life into it. Stuff Happening in a vacuum excites no one. Unless the contents of the vacuum explode all over the main character, then things start moving.

20

Why do you think that most of the Calligraphy contributors are women? Can that change and should it?

It’s interesting! I wonder if frum girls naturally have more opportunities to practice creative writing during their school years, while similar chances may be less available for boys. There are also so many fiction courses and writing groups geared toward frum women, but fewer for men. There may be tens of frum male writers who haven’t yet tried fiction and don’t realize they could be the next Hemingway.

Bottom line: We appreciate good stories, whether they’re written by a male, female, teen, or child prodigy. If it works well, we’re thrilled. So, fiction-inclined men — consider this an open invitation to submit. We love seeing fiction produced through different lenses; it’s definitely in line with our goal of curating a diverse and interesting collection for our readers. (And by diverse I mean heavy on the shidduch stories, and by interesting I mean some of them can be historical fiction shidduch stories. Those work too.)

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1031)

Oops! We could not locate your form.