Shtetl in Real Time

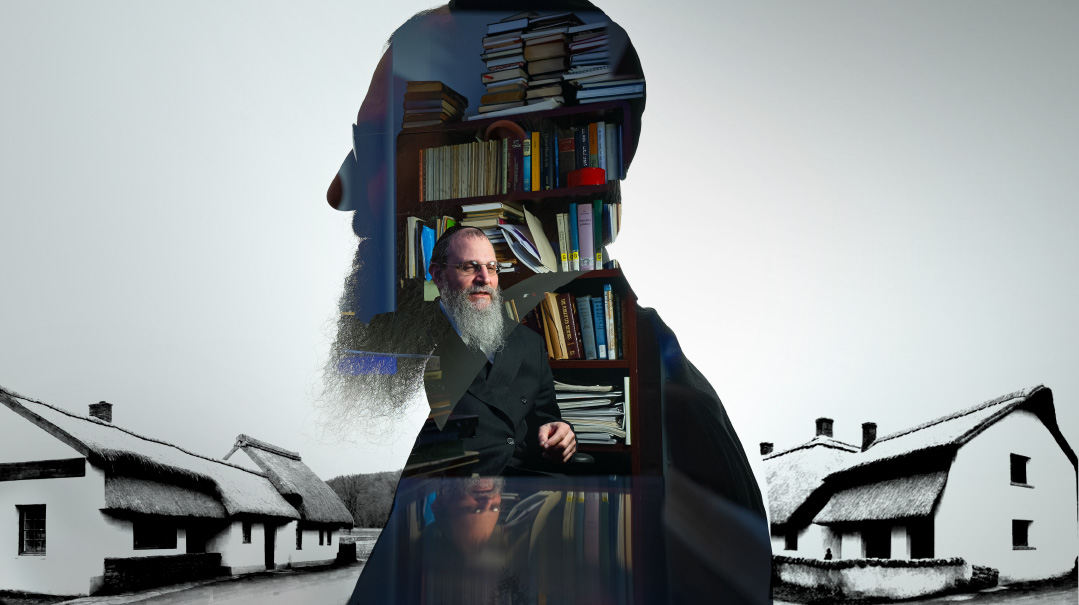

Researcher Michoel Rotenfeld revived a forgotten manuscript of a lost world

Photos: Naftoli Goldgrab

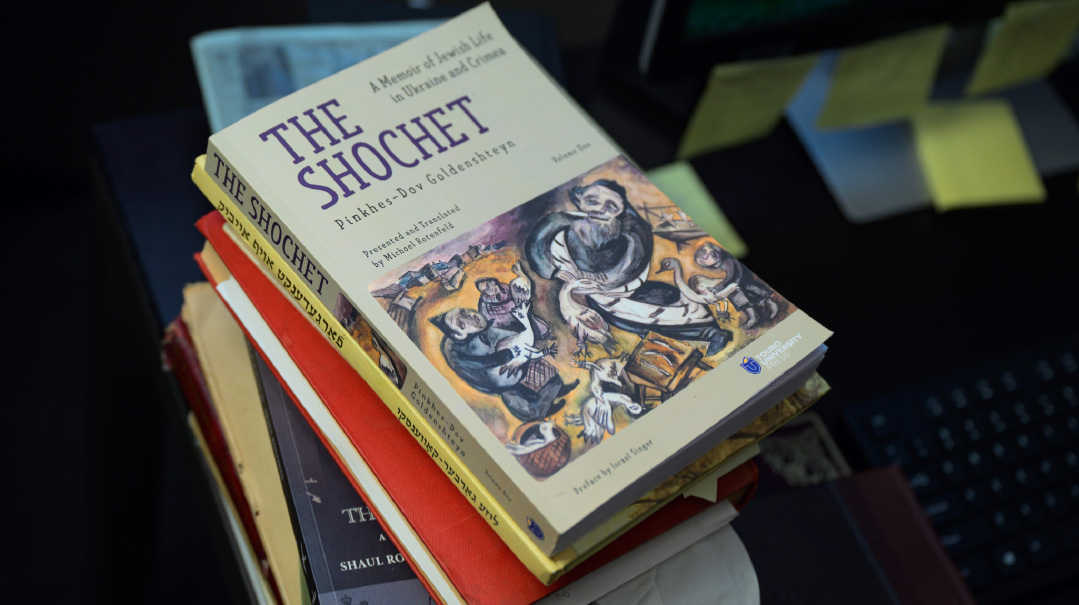

Many Jews grow up with nostalgic, Fiddler-on-the-Roof-style imaginings of the simple, pious life of the shtetl. But do such portrayals reflect the true reality of those times? Thanks to Michoel Rotenfeld’s new English-language translation of a Yiddish autobiography, The Shochet (1929), we now have a detailed, vivid, and unvarnished view of life in Ukraine in the second half of the 19th century. The author, Pinkhes-Dov Goldenshteyn (Pinye-Ber), an orphan from the town of Tiraspol, spares no details as he tells it like he saw it, and brings us along on his journeys through Eastern Europe, Crimea, and finally Eretz Yisrael.

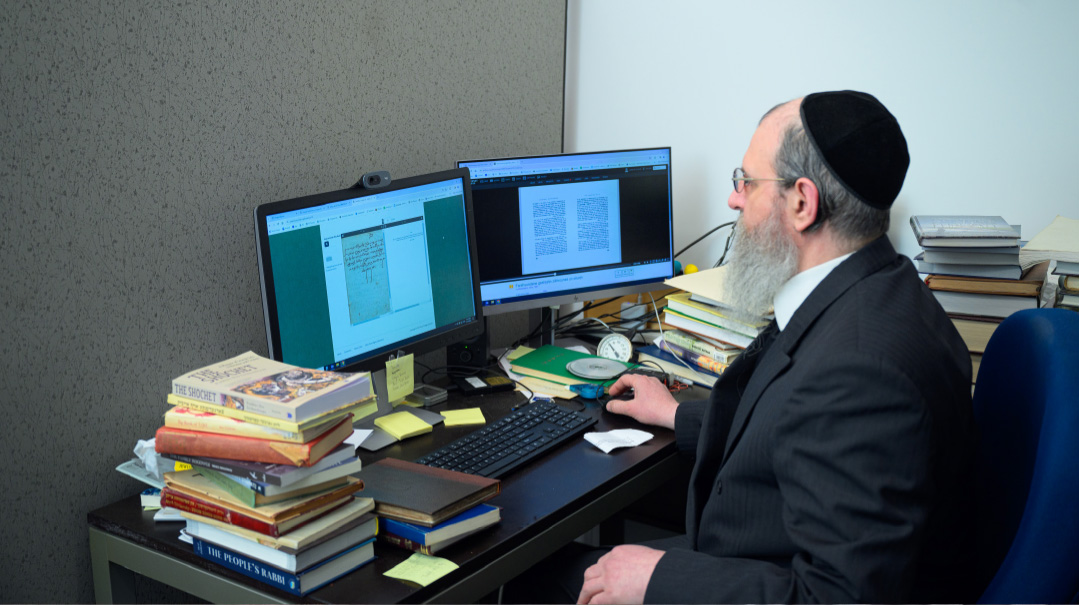

“Most autobiographies during that time were written by maskilim,” explains Mr. Rotenfeld, whom we find half-hidden behind stacks of books at his desk at Touro University’s Cross River campus on 43rd Street in Manhattan, where he serves as associate director of libraries. “The maskilim would begin by talking about their impoverished, benighted childhoods in the shtetls and show how they rose to greater enlightenment and prosperity as they abandoned their origins. The Shochet is perhaps the only autobiography written by a frum Yid who stayed firm in his Yiddishkeit and related daily life in detail.”

Published by Touro University Press, The Shochet has been enthusiastically received as a major contribution to scholarship on Jewish life in Eastern Europe. It has been compared in significance to The Memoirs of Gluckl of Hameln, a 17th-century autobiography depicting the life of a Jewish woman in Germany. Both are frank, detailed accounts of frum Jewish life, a window into daily life that reveals both how much, and how little, has changed.

“This fills a unique niche as an account of Jewish communal life,” says Dr. Israel Singer, professor of Contemporary Jewry at Touro University, who wrote the preface to the book. “It’s a close-up of the life of klei kodesh in those days, arguably the first published account. It is also perhaps the first book about someone who decided to go live in Eretz Yisrael before the First World War.”

Michoel Rotenfeld’s journey to finding and translating this unique work took more than two decades, involving travel to Eretz Yisrael and Ukraine, consultation with Yiddish experts, and countless hours of research (evidenced by the lengthy introduction and bibliography at the end of the book). It was a journey brightened by many sparks of Hashgachah pratis.

“I would need more information about a certain subject matter I was researching for the book, and then I would come across a book on the subject in a used book store,” he says. “I searched for the author’s relatives, and found one who’d been looking to find a translator.”

IT was in 1988, while learning in Kfar Chabad and researching an unrelated subject, that Michoel Rotenfeld first came across a reference to Pinkhes-Dov’s autobiography. While Rotenfeld was researching a certain subject matter, he was intrigued and asked around to see if anyone had heard of this book. “You should call Yehoshua Mondshine,” he was told. (Rabbi Mondshine z”l was a renowned chassidic historian.) When he did, to his surprise, Rabbi Mondshine exclaimed, “I just wrote an article about it!”

Rotenfeld read Mondshine’s overview of Pinkhes-Dov’s book in one of the three volumes of Mondshine’s Kerem Chabad, and it left him even more determined to read the book itself. But in the late 1980s, online book sites had yet to be developed, and his search proved fruitless. It would take years before Rotenfeld procured a copy in 1997.

“I sent a request to the Yiddish Book Center in Amhurst,” he relates, referring to the country’s largest repository of Yiddish-language books. “At the time, they’d have volunteer college students come in in the summers and help with people’s requests for books. If they had more than five copies of a book, they’d sell it to you. I bought my copy for two dollars and ninety cents.” The copy he received was missing a few pages and yellowing, but he made Xerox copies on acid-free paper of the missing pages from a copy in a research library.

When he finally read the memoir, he found himself profoundly moved and impressed. Pinye-Ber’s Yiddish is far from literary, but he is a compelling storyteller who transports the reader into the struggles of shtetl life, with the occasional barb of humor or sarcasm.

“I love autobiographies, and I’ve read scores of them,” Rotenfeld says. “This was the first one to really capture the daily life of a frum Jew. I was captivated by its honesty and by the way Pinye-Ber tries to grow in ruchniyus despite his hard life and many setbacks.

“He was a true chassid. He identified his trials with those depicted in the Chumash. He had a deep sense of Hashgachah pratis, and he strove to remain b’simchah no matter what happened to him.”

In the course of his research, Rotenfeld came across a review of The Shochet written in 1930 for Der Tog by the prominent Yiddish critic Shmuel Niger, at the behest of Pinye-Ber’s son.

“Niger himself wondered to his readers, ‘What compelled me to keep reading about this very mundane life?’ ” Rotenfeld relates. But even at the time, almost a century ago, Niger concluded that the “mundane life” of Pinye-Ber ultimately “told the reader about the typical life of yesteryear at greater length and more thoroughly than those who initially took upon themselves as a goal to be the historians of those eras and environs.”

Fascinatingly, as Rotenfeld immersed himself in research about Pinye-Ber, he found that their lives intersected across the centuries. Both their families come from the same region, and like Rotenfeld, Pinye-Ber considered himself a Lubavitcher chassid. While researching for the translation, Rotenfeld came across the autobiography of a man named A. S. Melamed, who like Pinye-Ber, had lived in Crimea. Melamed had grown up in the same Ukrainian town as Rotenfeld’s own ancestors and mentions them in dozens of pages, from his great-grandfather and great-aunts back to his great-great-great-grandfather in the 1870s. Another connection with Pinye-Ber is that Rotenfeld had an ancestor who was a Lubavitcher shochet and baal madreigah (person of spiritual stature).

Other family connections between the Rotenfelds and the Goldenshteyns (Pinye-Ber’s family) came to light almost immediately. Pinye-Ber lived in Petach Tikvah at the end of his life, where Rotenfeld’s grandparents had lived and kept a bookstore.

“I’m sure my grandfather must have sold his book, and since he was a voracious reader, he quite likely read it,” he says. “Both my father’s grandfathers davened in Petach Tikvah’s Great Synagogue, as did Pinye-Ber. They certainly knew each other, since in those days the town’s population was less than 5,000 people and all of the adults knew each other then, which I heard from the older generation.”

When Rotenfeld visited Pinye-Ber’s gravesite and that of his second wife Feyge, he found that Feyge was buried right next to his great-grandmother and her mother.

When it came to locating Pinye-Ber’s descendants, Rabbi Mondshine proved extremely helpful. He put Rotenfeld in touch with a man who knew Pinye-Ber’s granddaughter, Aliza Goldenshteyn Bernfeld of Petach Tikva. Aliza, who passed away in 2008, was able to provide him with information about the family and put him in contact with a cousin in the US, great-granddaughter Cynthia Unterberg. As fortune had it, Cynthia had actually been looking for someone to translate the book. “She had a copy, but she didn’t know how to read it,” Rotenfeld says. “But the family talked about it often, and that’s how I came to undertake the job.”

In the process of working on the book, Rotenfeld would connect to many members of Pinye-Ber’s mishpachah. The Lubavitch connection persisted as well: It turned out that Aliza’s grandson was someone he’d known in Kfar Chabad, while Cynthia herself was connected to Chabad of Midtown Manhattan. When her grandson became bar mitzvah, Rotenfeld joined the family to help the boy lay tefillin, and discussed that the boy’s Hebrew birthday, yud-daled Kislev, was the yahrtzeit of Pinye-Ber.

Thomas Hobbes famously said that life is “nasty, brutish, and short.” While Torah observance may protect Jews from being brutish, life in Pinye-Ber’s time was certainly grueling and short.

Death was a common visitor in the cold, poverty-stricken shtetlach of Ukraine. Pinye-Ber tells us in his first chapter that his parents lost two of their eight children in early childhood. He, the youngest of the family, lost his parents by the age of seven; his mother, whom he describes as a tzadeikes (“the most pious woman in Tiraspol”) exhausted herself taking care of a large family and selling housewares, and died at age 38. Her husband, a talmid chacham, died a year and a half later because, “he could not stand the pain and poverty of his loss.” The oldest remaining children were married, but the two youngest were shuttled back and forth between relatives.

The poverty he describes is heartbreaking. “Ukraine was a third-world country then. To some extent it still is,” Rotenfeld says. “I was there in 2004, and one town I visited was so small you couldn’t buy bread. At lunch people would eat homemade rolls, and that was their whole meal.

“There’s an instance in the autobiography where Pinye-Ber’s sisters go buy hot water from a store. Who buys hot water? I thought. I consulted with an elderly Eastern European Jew, and he explained to me that heating water at home would require them to make a fire.”

Homes had dirt floors and no running water; in the winter people sealed their windows with peat to keep out the cold. When Pinye-Ber marries, his wife’s dowry consists of two silver spoons, a salt shaker, a noodle board, and a string of pearls. It was common for people to go to bed with empty stomachs because there simply was not enough food.

Pinye-Ber describes his family as one in which Torah learning was prized; he says it would have been considered a shanda (a disgrace) to marry into a family of artisans. (Even working as a house servant, or shtub meshares, which he did briefly as a youngster, was considered a step above, especially if a person worked for relatives.) Unfortunately, talmidei chachamim had few options for making a living beyond working as a melamed, which didn’t pay enough to support a family. Then, as now, it often fell to their pious and idealistic wives to supplement the family income by engaging in some sort of commerce.

Parents who acquired a talmid chacham as a son-in-law would generally pledge a certain number of years of kest (having the couple live with them and eat at their table), but the arrangement was not meant to be indefinite. And there were some sons-in-law who abused their status as Torah learners. Pinye-Ber speaks with obvious disgust of his sister’s husband Shloyme-Leyzer, reputed to be a distinguished Torah learner, who “only knew how to sit in the beis medrash and tell miracle stories of tzaddikim. In general, he was a loafer who was used to others preparing his food for him, cleaning his clothes, and giving him a groschen on the side for his small expenditures…. But his wife and children’s expenses? He had no interest in that.” (His wife Tzipe died young, leaving a daughter of three years old and a baby of three months.)

Pinye-Ber does not hesitate to describe himself as a wild child. (Today we might say he was “acting out” his grief and anger at having lost both parents and being shuttled from relative to relative.) Cheder was a miserable experience that he describes as “a prison and the rebbi was no better than a Spanish inquisitor.” He was delighted to be pulled out of cheder for his mother’s funeral, until reality set in.

When his father was niftar not long after, Pinye-Ber was passed around; at one point his sisters send him off with a man who promised to “make a mensch out of him,” and he finds himself required to supervise a windmill in a poor, isolated area. He manages to escape and makes his way back to his sisters. A few years pass in which he works as a house servant, but there he has a vivid dream of his father bringing him to a palace, which he interprets as meaning that he needs to return to Torah study. Realizing painfully that he is forgetting his Torah learning, he runs away to find a beis medrash, depending on the kindness and contributions of strangers to get himself there.

There he excels, gaining skill as a chazzan as well, and before he knows it his old employer arranges for him to get engaged to his friend Shulem-Itsye’s daughter at age 16. He accepts on the condition that Shulem-Itsye register him as his son (it was illegal to remain unregistered, and as the “son” of a former soldier, he would be exempt from conscription).

After meeting some Lubavitcher chassidim, Pinye-Ber is so favorably impressed that he decides to become one of them. He likes their combination of warmth, prayer, and religious scholarship, which he compares favorably to other chassidic branches that, in his eyes, were more concerned with making l’chayims and telling stories than serious learning. He travels to Lubavitch to visit the Tzemach Tzedek and gives him a kvittel, and in response, the Rebbe tells him to put off his marriage until after he turns 19, and in the interim to learn in the yeshivah in Shklov.

At one point he is so curious about the Rebbe that he hides in the beis medrash after everyone has left and peeks through a keyhole to watch the Rebbe in his study. He is rewarded with glimpses of the Rebbe, dressed in white, learning in a room with walls covered with seforim, writing and occasionally partaking of some food. “He looked like an angel of G-d,” Pinye-Ber says.

HE endures grueling travels back and forth to arrange his registration papers, including a stint as a melamed in Bruditshesht in 1866, where a cholera epidemic kills many and the fast of Tishah B’Av is annulled, and visits Kishinev the following July to visit a niece, when a fire destroys 100 homes. Later that year, after a harrowing trip, he was zocheh to bring an esrog to the Lyever Rebbe.

By the time Pinye-Ber reaches marriageable age, his in-laws have lost all their money, and he hesitates to go through with the shidduch (they have nothing else to offer in terms of yichus or scholarship). But he is advised to proceed, and finds that his new wife, although unschooled, needs only some polishing to become a gem.

Pinye-Ber tries his hand at being a merchant and a melamed, and ultimately trains to become a shochet. “Today our Jewish professionals earn a living that, while often not large, is something they can live on,” Dr. Israel Singer points out. “That was not the case in Pinye-Ber’s day, and he struggled.” Pinye-Ber travels far to find an uncle who might help him, only to find the uncle is also impoverished. At one point, with his wife expecting, he decides this is his last chance to go to the Lubavitcher Rebbe, and travels to meet the Rebbe Maharash (who succeeded his father the Tzemach Tzedek). After his long travels, when he finally meets him, the Maharash tells him to return home right away.

Confused and disappointed, Pinye-Ber doesn’t listen, because he has heard that a relative of the Rebbe is getting married and the Rebbe will be holding a tish. He stays, enjoys himself immensely, and as he’s too far down the table to see the Rebbe clearly, he crawls under the table to crouch at the Rebbe’s feet and listen to his clever conversation and words of Torah. “This made my entire trip worth the effort,” he writes.

When he returns home, he finds out that the delay caused him to miss a job opportunity that went to someone else. Eventually he secures a position as a shochet, and for a brief period, he and his wife live in relative security. But finally, political conflicts in the town and his meager income lead him to accept a post in Crimea, in an area populated mostly by Muslims and uneducated Jews.

Unfortunately, despite his many trials, most of Pinye-Ber’s children did not perpetuate his devotion to Torah. “Just about all of them did not follow his path,” Rotenfeld says. “He knew three of his sons had immigrated to Portland and were most likely eating treif. Two of his children did remain frum, but the grandchildren didn’t retain Orthodox observance.”

Pinye-Ber himself was far too great a baal bitachon to have been tempted by the Enlightenment. His joy in Torah learning, strong family piety, and zechus avos most likely would have kept him anchored in Torah even had he encountered such ideas.

Volume II, slated for publication in September, continues Pinye-Ber’s journey: his almost 35 years as a shochet in the Crimea (an area Rotenfeld characterizes as “the Wild West”), his encounters with the Sdei Chemed, who moved from Eretz Yisrael to Crimea for 20 years where he established a yeshivah, and finally his decision to finish his life in the Holy Land, where he moved in 1913 (and soon found himself dodging gunfire between the Turks and the British during World War I). He ultimately settled in Petach Tikvah, where he became acquainted with Rav Yisrael Abba Citron (the son-in-law of the Rogatchover Gaon and rav of the city) and probably other great talmidei chachamim.

For an ordinary Jew, Pinye-Ber had an extraordinary life. But then again, for a Jew, perhaps that’s not really so atypical?

A Life in Books

After spending over 20 years working on The Shochet, Rotenfeld grew to feel extremely close to his subject, almost as if he were a family member; at times, while speaking about Pinye Ber, he becomes so deeply moved he has to pause for a moment to collect himself.

The project was a natural outgrowth of Rotenfeld’s twin passions: his love for Jewish books and love of the Yiddish language. He comes by them honestly — his paternal grandfather owned a bookstore in Petach Tikvah, and met Michoel’s grandmother when she came into the store to buy a book. Even his own parents met because of a book. His father, who came to the U.S. in 1953, borrowed a book from a woman he knew. When he came to her house to return it, her sister answered the door, and a match was made.

Michoel spent some time learning in Eretz Yisrael as a young man in Kfar Chabad, where the Yiddish he’d spoken as a youth with his elderly relatives served him well. He returned to the U.S. and spent some time as a melamed, but decided it wasn’t the best fit for him. “I always had an interest in libraries,” he says. “I was involved in the libraries in my shul and in my yeshivahs.” His mother was the first to suggest, “Why don’t you become a librarian?”

He enrolled at Pratt University, earning his MLIS. His first jobs were in the corporate world, managing libraries for companies such as American Insurance Services Group. In his spare time, he did some dealing in seforim, once acquiring a collection of 11,000 books to donate to the Yiddish Book Center in Massachusetts. “Jewish books from the 1920s and ’30s were predominantly in Yiddish,” he explains. “Back then there wasn’t a Jewish market for books in English or Hebrew.”

When his company downsized, he began to look elsewhere and saw an opening at Touro College. He accepted Touro’s offer just as he received his final paycheck from American Insurance Services Group, finding a congenial home in a scholarly Jewish environment, so congenial, in fact, that he’s still there 23 years later.

His field has transformed immensely over the past two decades due to the introduction of technology. “When I began, databases were in their infancy,” he says. “Now it’s an industry of billions of dollars.” He acquired his technological know-how mostly on the job, attending conferences, speaking to vendors, and researching on his own. Today, when one of Touro’s 36 schools needs new electronic resources, his job is to canvass the available options, contact vendors, arrange optimal pricing, and then handling the licensing and online access. “I learned my negotiation skills on the job,” he says with a shrug.

Under his direction are the people handling Touro’s institutional archives — 50 years of documentation, including all of Rabbi Dr. Bernard Lander’s papers — as well as people cataloguing and processing Hebrew and English books, and purchasing everything from pencils to licensing contracts that collectively represent millions of dollars. He coordinated the digitalization of the Encyclopedia of the Founders and Builders of Israel by David Tidhar — all 19 volumes — and has received millions of page views since. “I put in a lot of overtime,” he admits with a smile.

His newest job title is director of Touro University Library’s Project Zikaron, which is a collection of historical materials regarding Jewish communities all over the world. The project involves digitizing and collating masses of material that will now be more easily available to historians and other researchers — a database that would have been ever so useful to Rotenfeld as he researched The Shochet.

Losing Himself in Translation

Rabbi Yitzchok Stroh, Rotenfeld’s friend, states that Michoel has an unusually deep knowledge of Yiddish for someone of his generation. “Michoel knew many of the old timers in Crown Heights, such as Yehoshua Dubrawsky, who used to write down the Rebbe’s sichos,” he says. “He picked up their Yiddish, including obscure words many other people don’t know, and he became acquainted with all the Yiddish experts out there, even the nonreligious ones.”

Yet despite his impressive command of the language, Pinye-Ber’s autobiography was a daunting challenge. Rotenfeld was no stranger to translation, having translated many shorter articles, and private papers. Those projects went smoothly. But Pinye-Ber’s memoir was a horse of a different color. “He wrote in the best Yiddish he could, but it was an unsophisticated Yiddish,” Rotenfeld says. “It wasn’t well punctuated, and many idioms and words were unfamiliar. I had to keep reading and rereading it to make sense of some of it.”

He consulted his lineup of Yiddish experts, including a Russian immigrant who was a native of Pinye-Ber’s hometown of Tiraspol, who used to take care of a mikveh in Boro Park. Rotenfeld spent many hours trying to make sense of obscure and idiomatic phrases. For example, Pinye-Ber refers to a man named Boye, and Rotenfeld could not determine what name that would have been a nickname for. It was Rabbi Stroh who volunteered that he’d known a family with a son named Baruch who was nicknamed Boye.

The chronology was confounding as well. Pinye-Ber writes that he was born in 1842, but Rotenfeld says it’s clear he was born later, in 1848. He may have erred regarding his year of birth because at one point he deliberately made himself out to be ten years older to help his oldest son escape conscription. At any rate, practically all the years he mentions did not jibe, and Rotenfeld spent hours trying to puzzle it all out and construct a logical timeline. “I would spread papers across the floor and spend hours reconciling the dates,” he says, “but in the end I worked it all out. Though he was poor in remembering years, he was outstanding in remembering the chronology of the events in his life, which have been confirmed by a number of outside sources.”

He devoted equally meticulous attention to figuring out the exact geographical locations in the book. The librarians in the Map Reading Room of the Library of Congress were extremely helpful in helping Rotenfeld find certain rural locations that he could not locate on his own.

Pinye-Ber himself notes in his memoir that many Jews deliberately made no official registration of their birth in order to avoid conscription. He describes heartbreaking scenes of “snatchers” coming to his village and seizing boys to hand over to the soldiers. “Mothers dashed about like poisoned wolves and their cries reached the seventh heaven,” he writes, later describing the scene of “little soldier-boys walking — many, many of them… not quite walking but rather dragging themselves along… crawling in the mud while many grown soldiers marched alongside and drove them mercilessly while the area resounded with their cruel shouting.”

One Rosh Hashanah morning, when the chappers arrived, his quick-thinking sister Ite pulled him into the women’s section, hid him under her skirts, and walked home with him like that. “So I suffered throughout that winter,” he writes. “I was constantly forced to hide in various places that my sisters would think up for me: at times in a cellar, at other times in an attic, and many times simply with a good friend.” Most of the captured boys were lost forever to their people, but there were some who came back. Cruelly enough, the miserable fate of having served as a Cantonist was considered a blot on one’s social standing even for those who resumed Jewish observance.

Oops! We could not locate your form.