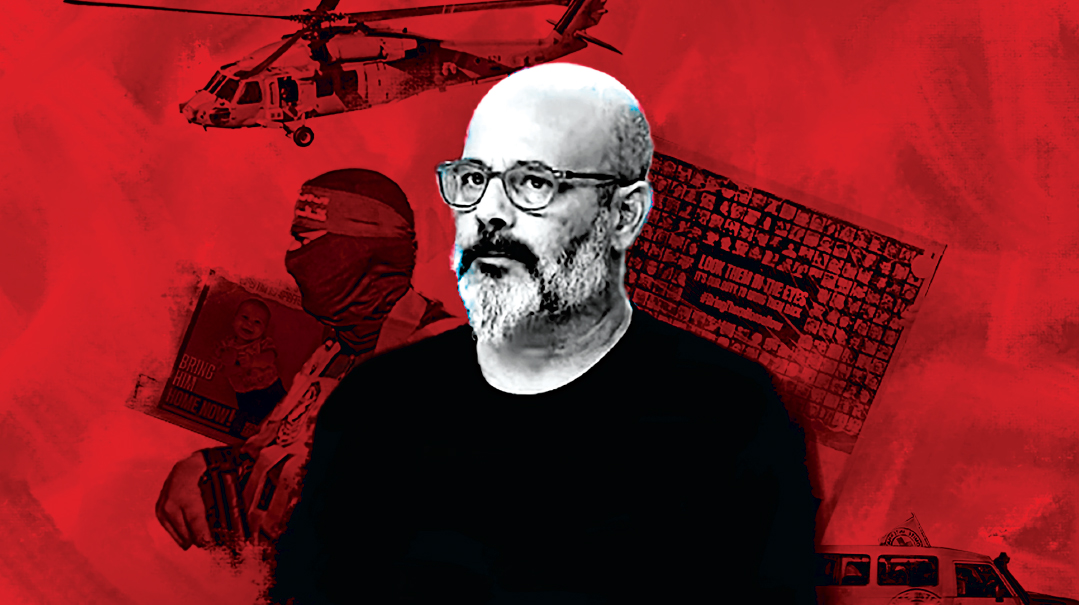

Home at Last

Chen Avigdori embraces his family as they return from captivity, helping to heal family scars while discovering a language of resilience he never knew

C

hen Avigdori is a well-known media personality who’s worked for the last two decades as a comedy scriptwriter for both kids’ and adult programming on Israeli television. But the last seven weeks, until his kidnapped family was finally reunited, were more horrific and surreal than any plot or screenplay he could have ever dreamed up.

The Avigdoris live in Hod Hasharon, a well-appointed town in Israel’s center, north of Tel Aviv and Petach Tikvah. It’s not a border city and not a target for terrorist attacks. Chen, 53, is a television writer who rubs elbows with the rich and famous; his wife Sharon, 52, is a therapist specializing in treating youngsters on the autism spectrum; and their two children — 16-year-old son Omer and 12-year-old daughter Noam — rounded out the picture of a hard-working, well-connected, career-oriented, upper-crust Israeli family.

Until October 7.

The Simchas Torah massacre caught Sharon and Noam in the crosshairs of brutal terrorists who charged into two dozen communities in the south — including the once verdant, pastoral Kibbutz Be’eri, now a burnt-out shell where a hundred people were slaughtered and dozens more kidnapped to Gaza.

Sharon had taken her daughter to Be’eri to spend the holiday weekend with her brother and sister-in-law, Avshalom and Shoshan Haran, longtime kibbutz members whose sprawling grounds and swimming pool made their home a sought-after family getaway location. (Chen decided to stay home with Omer, who had made other plans with friends.)

But by the end of that horrifying Shabbos, Avshalom Haran was murdered, as were Shoshan’s sister Lilach Kipnis, her husband Evyatar, and his caregiver, while the seven remaining members of the Haran family were hauled away alive into captivity: Shoshan Haran, her daughter and son-in-law Adi and Tal Shoham and their three-year-old Yahel and eight-year-old Naveh, plus Sharon and Noam Avigdori.

All of the family members have now been released except for Tal Shoham, who’s still being held captive somewhere underground in Gaza.

After an emotionally charged reunion whose images went viral and a two-day hospital stay, Sharon and Noam are back home, but, as Chen Avigdori says, while Chapter 1 is over, Chapter 2 is just beginning.

“They are really fine, both physically and mentally, under the circumstances,” Avigdori tells Mishpacha. “Their readjustment will obviously take time, but we’re a strong family with a strong foundation. Now we’ll need to build our family all over again and I know I personally have a lot of work in front of me, but I’m confident in my wife’s strength and courage, and I know we’ll figure out how to remain a solid family unit, like we’ve been for the last 20 years.”

Chen is the proud secularist, but he says that “Sharon is the one that brings emunah into our home. She lights Shabbos candles, and is strict about keeping kosher inside and outside the home.”

While she grew up in a staunchly secular family, one brother got closer to Judaism and she followed him. “I’m sure her strong emunah and connection helped her endure the captivity,” Avigdori says.

Over the last week and a half, all eyes have been turned on the freed hostages: What did they go through? Were they tortured? What were their conditions like? Did they have food? A mattress? Facilities?

Perhaps the public is confused: The hostages for the most part looked pretty good when they emerged (Hamas obviously made sure of that), but Professor Itai Pessach of Sheba Hospital, who spoke to the press last week, said of the released captives that “some of them suffer from complex underlying illnesses and some from injuries they sustained when they were abducted and also suffered during captivity… Our feelings waver from happiness and excitement to pain and sorrow and at times even horror in view of the injuries we treat and the difficult stories we’re exposed to — things we thought belonged to a different era in history.”

Avigdori, for his part, isn’t talking.

“While there have been some social media postings, I, for one, am not saying anything — not what they experienced, not where they were being held, nothing. It’s all classified at this point,” he states, “and it’s also private. You can draw your own conclusions from all the stories flying around, but personal trauma doesn’t have to become public property.”

In addition to the raw trauma of captivity, Sharon lost three family members in the massacre, including her brother, and only discovered that after she was released.

“Sharon, like many of the other hostages who are now discovering that they lost family members, was informed of her brother’s murder and the full picture of the massacre only once she came home,” he says. “The hostages had no idea that entire communities were wiped out and burned to the ground.”

“Missing” Goes Either Way

Chen Avigdori’s last communication with his family was on the morning of October 7, soon after they entered the family’s safe room. Later that morning, his brother-in-law Avshalom texted him that they were in “big trouble,” and then communication was cut off.

Initially after the attack, Sharon and Noam were listed as missing, and only two weeks later was Avigdori informed that they were among the kidnapped in Gaza. ZAKA and military personnel were working around the clock trying to locate and identify bodies — and while Avigdori’s brother-in-law was eventually discovered murdered, as long as Sharon and Noam had not yet been declared dead, there was a chance they were still alive.

During those weeks, Avigdori went into overdrive, using his extensive media and political connections to try to find a sign of life, while his extended family created a kind of situation room for any new developments.

What he did know initially was that the Haran home, while burnt, was empty of bodies, and that the cell phone of one of the family members was tracked to Gaza. They also discovered that Omer’s credit card, which was in his mother Sharon’s wallet, had been scanned in a Gaza supermarket.

“But so far,” he remembers, “those were just hints, not confirmations.”

It wasn’t that the government was hiding information, he clarifies. At that point, they really didn’t know.

“As soon as they had information — you know, with their own high-end intelligence fronts — they immediately shared it with us, but for the first two weeks, Sharon’s and Noam’s status was ‘missing.’ And until that status was changed to ‘kidnapped,’ it was excruciating. Because missing can go both ways — either they’re kidnapped, or they’re dead. So during this horrible two weeks of not knowing, we didn’t give any interviews, didn’t do any publicity work. Because how can I say, ‘Save my wife, save my daughter,’ if she’s really dead?

“As soon as the government had information, our personal liaison immediately made an appointment and came over. They were very good to us, sharing whatever they knew. They understood the mental state of someone whose loved ones are missing.”

And once his wife and daughter were confirmed as captives, Avigdori, with his media smarts, became one of the familiar faces of the families’ campaign to free the hostages.

Let’s Make a Deal

People today face many challenges and there is no shortage of grief — whether it’s a sick child, death of a loved one, or other painful traumas — yet there are support groups for these challenges, along with tools and therapies. But, says Avigdori, who can help you process a Hamas kidnapping to Gaza of a family member? Who’s even gone through such an ordeal? Nobody, he says, can get you prepared for this kind of a challenge.

And so, how did he keep his equilibrium?

“If you have a mission and you have a goal, and you are very, very busy on the national and international fronts, it really saves you from falling into despair,” he says. He also tried to keep working, producing shows and writing scripts. And, he admits, he would sometimes move into the fantasy world of good guys and bad guys pushing the buttons on the family PlayStation. (“I don’t have the ability to just go out and kill all the Hamas bad guys,” he joked to a reporter, “so this way, I can slaughter an entire international evil syndicate and get out my revenge.”)

Now that he and Omer were on their own, they made a deal with each other: “I told him, ‘I’m not going to withhold any information from you, and I don’t want you to withhold any of your emotional stuff from me.’ This deal worked great. At the end of every day, we had sort of a debriefing, we talked about everything, not just the situation — we’d cry together, and then we’d go to sleep. It changed our relationship too. In the beginning I was his support, but pretty soon, Omer, a really smart and sensitive kid, became my strength.”

Avigdori acknowledges what anyone who goes through trauma knows: No one can go through such a horrible experience and come out on the other side unchanged. “For me personally, I noticed two things,” he relates. “I was never a touchy-feely type — I’d prefer a handshake over a hug anytime. But now, I love those hugs. Because there’s a deep connection that emerges during these times. People in pain often like to isolate, and I’m the type that doesn’t like my space invaded. But now I was in a new place I’d never been in before. People I didn’t know would come up to me on the street and hug me, telling me, ‘Hi, Chen, I’m with you, and I just want to give you a hug.’ ”

What Do You Say?

The Avigdoris are finally moving into the next phase — after the miracle they’d been praying and hoping for, it’s time to reintegrate to real life after 50 horrific days. But they can’t erase the impact of the captivity; there’s no just getting up the next morning and starting up where you left off.

“Those seven weeks were completely surreal and incomprehensible and even the release was surrealistic. My family is now back, after spending 50 days being held captive by a ruthless, radical Islamic terrorist organization — and when I think about it, it still sounds like the plot of a horror movie and not something out of my real life.”

And the last four days before the Saturday night release on November 25 were, in a way, a preparation for how much one’s nerves can stretch.

On Wednesday, four days before his family members were released, Avigdori, along with the entire world, had heard the rumors of a deal: a dozen or so hostages a day for the next four days, dependent on a temporary cease-fire and release of Palestinian prisoners from Israeli jails. But who would be on those lists?

It didn’t even matter — because on Wednesday, the deal nearly collapsed. Now it was Thursday, and the swap, it seemed, had been reinstated. But when Israel was given a list of the first batch of names, the initial 13 women and children, Sharon and Noam Avigdori weren’t on it.

“I was prepared and not prepared for that disappointment,” Chen remembers. “I knew there were younger children being held captive that would probably be released first. But when I got the call from our liaison that they weren’t on the list — what can I tell you? I may have looked cool on the outside, but inside I was crushed.”

There were rumors that they’d be released in the second round, on Motzaei Shabbos, but Avigdori did his best not to get his hopes up, even as he was given instructions by the social workers handling the freed hostages: that Sharon and Noam have been together this entire time, facing their captives together, and they might initially be inseparable, so let them adjust at their own pace to regular family relationships; don’t press for information — better to let them tell you at their own pace; and don’t become overwhelmed if they exhibit unpredictable symptoms related to trauma.

And then it was official: Sharon and Noam would be released in the second round. Avigdori, though, after seven weeks of disappointment and dashed hopes, didn’t believe it until his wife and daughter were seen on camera through the side window of one of the Red Cross transportation vehicles.

“I can’t describe those seconds when I finally saw them, blurry picture as it was,” he says. “I think those were the happiest moments of my life — or maybe the happiest was the meeting in the hospital four hours later.”

But, he admits, amid the hugs and tears, it was a little awkward. What do you say to your spouse, to your daughter, who’ve been in captivity by depraved terrorists for almost two months? “Great to have you back? You’re looking good? We missed you so much? No matter what you say, it will come off as a cliché. At a certain point, I felt it was better not to say anything. And in fact, the biggest blessing was that the hospital allowed us to spend the night there. I woke up the next morning, looked around the room and counted the people: one wife, two children — here was my family, together. I cannot describe the pure joy.”

We Never Knew

For Avigdori, it’s now Chapter 2 of his personal story, but it’s also a national story that hasn’t ended.

While 102 hostages have been released, Israel believes that at least 130 hostages are still being held in Gaza, including another 17 women and two children, including the youngest hostage — ten-month-old Kfir Bibas, presumed to have been handed over to Islamic Jihad in southern Gaza with his four-year-old brother and parents.

“The fact that my wife and daughter are at home is not the end of the story for me. The mission has not yet been completed, and I’m going to keep on being active, keep up the fight until the last hostage is returned. Because this is not a local issue or even an Israeli issue — it’s an international issue, a basic humanitarian issue. No one my daughter’s age should ever be held captive, no one should have to go through that. It’s a minimum value of the Western world. Everyone should be advocating and fighting for the release of all the hostages until the very last one is released. This is what needs to be done. The how part, I can’t tell you. I’m just a comedy writer. I leave that up to the military and intelligence people in the field.”

Yet the parameters have moved. “Before, for me at least, it was ‘we have to get them out.’ Now, my family is facing the personal challenge of recovery, of rebuilding our personal lives, but I can’t forget the larger story. Because I know what it feels like to hold your daughter again after 50 days in captivity, and I want every family to experience that boundless joy and gratitude.”

And there’s another angle to his campaign as well. Avidgori was part of a delegation that met with rabbanim, and it was a huge eye-opener for him. He says he had no idea that there was even a spiritual angle to the war, to the fight for releasing the captives.

“We learned about what the children have been doing in cheder, about all the kabbalot of bochurim in yeshivahs and seminaries, all the Tehillim, the shemirat halashon initiatives — all that has been going on inside chareidi society and we knew nothing about it. And when we heard, we couldn’t really even understand it, because it’s so distant from our world. One of my goals now is to find a way to tell the secular public about this, even though these initiatives might seem foreign to us initially.

“I don’t really know what this hishtadlut is, what small children are accomplishing on a spiritual level for the war. What it means that a child in cheder takes upon himself learning extra Mishyanot by heart and not talking lashon hara for an entire day, or people making commitments about halachah, shemirat Shabbat, more modesty. I don’t know what that means, and neither does my sector. But that doesn’t mean we don’t want to know. We want these things publicized so that we can understand them and appreciate our brothers, realize that we’re all in this together.

“It made me realize how it doesn’t matter what you eat, how you dress, or what you do on Shabbat — we are all one nation, one people. This is something that has given me hope, not only for the hostages, but for the country’s future. I always assumed it was us against them — I never realized that there was this all-encompassing feeling of love and mutual responsibility. Maybe we can build something new out of the ashes.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 989)

Oops! We could not locate your form.