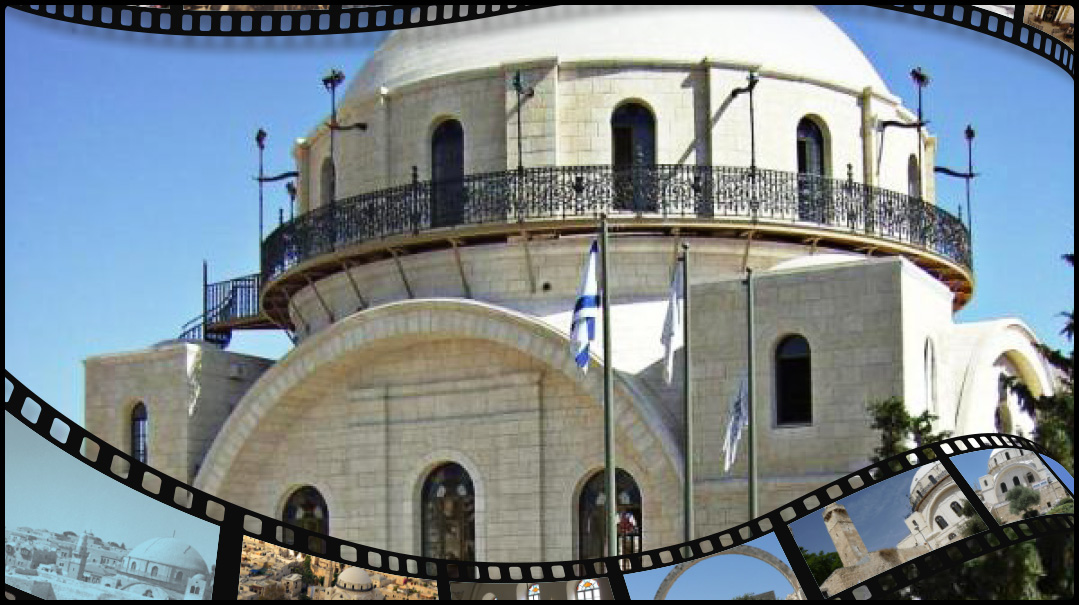

From Galus to Geulah —The Churvah

| July 12, 2022The story of the Churvah shows us this clearly: yes, galus can destroy — but never forever

IT'Sthat time of year again.

The time of year that we focus on the destruction of the Beis Hamikdash, on the pain and desolation of our galus.

But it’s also a time to look forward.

The month of Tammuz is a backward acronym for zemanei teshuvah memashmishim u’baim — the days of teshuvah are coming close. And then, in the even sadder month of Av, we know that the letters of the month’s name remind us: Elul ba, Elul is coming.

Because even in the destruction, even in the desolation, a Yid looks forward.

The story of the Churvah shows us this clearly: yes, galus can destroy — but never forever.

Hopeful Hearts

Long ago and far away, a movement was quietly taking place. The year was 1700, and the great sage, Rabi Yehudah Hachassid, was collecting followers from across Poland, Germany, and Moravia to join him on a harrowing and dangerous journey, a journey with a very special destination: Eretz Yisrael. Over 300 years ago, travel didn’t look anything like it does today; it was fraught with risk and very difficult. (It wasn’t until 200 years later that the Wright brothers got the very first “flying machine” into the air, and commercial flight was more than 240 years away!)

Rabi Yehudah Hachassid gathered together an intrepid group of travelers to make their treacherous way from Poland to Eretz Yisrael. By the time they reached Italy, on the way to Eretz Yisrael, their group numbered about 1,500 people, including many families. Sadly, by the time the group made it to their destination, many of the travelers had perished. The difficulties of travel and sickness had taken their lives.

In the fall of 1700, the surviving travelers arrived in Yerushalayim. They were ready to settle into the holy city and begin preparing to welcome the Mashiach.

Oops! We could not locate your form.