Finally, Here Is Yossele

Six decades later, Yossi Shuchmacher is still making peace with the players who made him the most famous name in the country

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Mishpacha archives

The last time their paths crossed was 60 years ago and they hadn’t seen each other since. But sometimes after six decades, something softens, reconciliation doesn’t seem so threatening, and it’s time to forgive and move on.

In the Davidson home in Jerusalem’s Bayit Vegan neighborhood, Uriel Davidson and his wife Gittel are excited about finally re-meeting their expected guest. It’s actually more of a closure for the soul of Uriel’s deceased mother, Ruth Ben David (Blau), who passed away 22 years ago. She was the one who impacted their guest’s life so many years before.

And then, a hesitant knock on the door, a round of shaking hands and clicking cameras. In walks Yossi Shuchmacher — a.k.a. Yossele, the child whose name was on everyone’s lips back in the early 1960s, whose disappearance caused a national furor and sleepless nights for the prime minister and the head of the Mossad.

Today, Yossi Shuchmacher, 70, a longtime resident of the mixed religious-secular Samarian town of Shaarei Tikvah and retired corporate strategist, is ready to put it all behind him — being hidden by his grandfather in Meah Shearim and other chareidi enclaves, being whisked away to Europe and then to America by a daring and savvy giyores named Ruth Ben David, and finally being located by the Mossad and reunited with his parents.

“It’s a lesson we can learn from Lot’s wife,” says Shuchmacher. “Sometimes it’s better not to look back.”

Reb Nachman Shtarkes survived Siberian torture and fought for Yiddishkeit with an iron will. There was no way he’d let his grandson go back to that G-dless wasteland

Point of No Return [Meah Shearim, Jerusalem]

“I believed what they told me, that my parents wanted to take me back to Russia and turn me into a goy.”

If you’re not a golden-ager and don’t remember the anti-religious taunts on the streets of Israel and beyond of “Where is Yossele?” a little background is in order. The saga began in 1958, when struggling Russian immigrants Ida and Alter Schumacher put their six-year-old son Yossele in the charge of his maternal grandfather, Reb Nachman Shtarkes. Shtarkes, a staunch Breslover chassid who survived Stalin’s Siberian gulag during World War II, was eventually granted an exit visa from the Soviet Union and settled with his wife and son Shalom in Meah Shearim. Another son, Ovadia, moved to London. Ida and Alter followed several years later with their two children, Yossele and ten-year-old Tzinah.

Ida and Alter were first sent to a transit camp in Nahariya, and then were given a tiny apartment on the dunes of Holon. With no means to support their children, they sent Tzinah to a religious boarding school in Kfar Chabad, and Yossele was happily sent to his grandfather, where it was no secret that his zeide would make sure to give him a strict chareidi education.

These were the years of suspicion and mistrust. The secular Zionist powers had taken Yemenite children and cut off their peyos, shipped Moroccan immigrants off to secular kibbutzim. In the Old Yishuv, there was a pervasive feeling of fear and panic of shemad, and people would do anything to keep Jewish children from the secular Zionist clutches.

These were also the years of austerity, when citizens accepted with equanimity the need for rationing of basic staples, and when the country was swept up in the kibbutz dogma, where it was considered noble for children not to live with their parents, but in a separate children’s home, seeing their parents for maybe an hour a day, so that the adults could devote all their energies to building the country.

The ideologies were so pitched all around, the passions so high, that real, vulnerable people and authentic and crucial relationships sometimes got sacrificed in the process — as long as it was all for a greater cause.

But not for Ida and Alter Schumacher. Rocked by hard times, they wrote to friends in Russia that perhaps they shouldn’t have come to Israel. Some of that correspondence fell into the hands of Reb Nachman Shtarkes, and he concluded that his daughter and son-in-law intended to go back to Russia with their children — because at the same time, they decided it was time to take back Yossele. Seething with fury, he decided not to give Yossele back to his parents. Reb Nachman was well acquainted with the disappointments and corruption of communism, and refused to have any part in his grandson’s return to that awful G-dless place he himself had narrowly escaped — losing an eye, three toes and even a son as a price for defending his Yiddishkeit. So he decided to keep Yossele with him and hide him until his parents’ perceived threat to take him back to the Soviet Union had passed.

Eventually Yossele could no longer hide among the children of Meah Shearim; the media was snooping around and a court order to return him to his mother had been issued. Reb Nachman would have to think of a more distant solution.

Yossele’s uncle Shalom Shtarkes took charge of the situation, hiding him in various chareidi enclaves, from Tzfas to Bnei Brak and finally to the Kot family in Moshav Komemiyus.

“I was a little boy from Meah Shearim cheder and I cooperated,” he tells Mishpacha. “I believed what they told me, that my parents wanted to take me back to Russia and turn me into a goy.”

Initially, although Yossele had been in hiding for months, the police showed little interest in the case. The Shuchmachers weren’t the first family to talk about returning to Russia, which was a source of great embarrassment to the Zionist government — every immigrant that returned to Russia was an indictment on Zionist ideology and the state’s absorption process. But when the story mushroomed into a chareidi cause of saving the boy from apostasy, the government switched sides.

It’s not clear at what point Nachman Shtarkes himself lost track of Yossele’s whereabouts or whether he preferred to be kept in the dark. By this time, though, his handlers realized their best chance of keeping Yossele protected was to spirit him out of the country.

But that would involve false passports, a network abroad, quick wit for evading the authorities, and a daring temperament. Who would take on such a mission?

Her Own Woman [Paris, France]

Because Ruth Ben-David was the very picture of discretion and rarely responded to anything published about her, fact and fiction wove themselves into a fascinating, if not always accurate, portrait of her life.

Few peoples’ lives have captured the collective imagination as that of Ruth Blau, whose name and escapades were intrinsically linked to the sensational side of the fledgling State. She first became famous in the early 1960s as Ruth Ben-David, the French-Catholic Jewish convert who became the linchpin in the “Yossele Affair”; then she married widowed Neturei Karta leader Rav Amram Blau in 1965, scandalizing the closed world of Mea Shearim; and her forays into Arab countries and contacts with enemy leaders to rescue Jews further piqued the interest of onlookers. But because she was the very picture of discretion and rarely responded to anything published about her, fact and fiction wove themselves into a fascinating, if not always accurate, portrait of her life. Even after her death in 2000 at age 80, her story continued to be the focus of intense curiosity.

What many people don’t know is that Ruth had a son, Claude, whose name was changed to Uriel upon his conversion as an 11-year-old together with Ruth in 1950; today he and his wife Gittel, a retired kindergarten teacher, are parents of eight and grandparents of many more.

For over half a century, Uriel Davidson has kept a low profile, avoided publicity, and resisted media attempts to interview him. But now that his mother has been gone for over 20 years, both he and Gittel prefer to honor her by speaking about her incredible life — and part of that meant reconnecting with Yossi Shuchmacher, closing the circuit of pain and suspicion.

Ruth Blau was born Madeline Ferraille in 1920 to a Catholic family in Calais. She married for the first time at age 19, had one son, and a year later divorced her husband. Her bravery became apparent during WW II when, as a member of the French Resistance, she helped save the lives of many people, including Jews. She then studied at the University of Toulouse and the Sorbonne. After living through the underground side of the war, the establishment of the State of Israel made a deep impression on her, and her first visit in 1949 ignited her with Zionist fervor. She even became a dues-paying member of French WIZO.

She converted to Judaism in 1950 in a Reform ceremony, taking on the name Ruth Ben-David.

At the time, the Jewish National Fund had launched a campaign to purchase trees in Israel, and whoever sold the largest number of trees would win a flight to the Holy Land. Uriel/Claude was a determined young fellow just like his mother, sold the most trees, and won the trip. Ruth joined her son, and that spiritually uplifting trip was life-altering: Ruth and Uriel came back and underwent Orthodox conversions.

Ruth was a shrewd businesswoman and made a fortune in textiles, investing most of her profits in real estate. But, Gittel told Mishpacha, for all her shrewdness, she was also intrinsically trusting, and she wound up being cheated by her partner. She even spent a month in prison on charges he trumped up against her, and had to sell off most of her properties to pay the legal fees.

In 1953 she decided to move to Israel, where she felt her conversion would not arouse the negative attention it had in Paris. She bought a small apartment and sent Uriel to school at the religious Kibbutz Yavneh. Several years later they moved back to France, and Ruth moved away from the Zionist ideology that had so captivated her, becoming close to Rebbe Itzikel and his son-in-law Rebbe Yankele of Pshevorsk. Uriel then attended the Satmar-affiliated yeshivah in Aix-Le-Bains in southern France. From there he went back to Israel and studied at Rav Shlomo Wolbe’s Yeshivas Be’er Yaakov (he is still close to Rav Shlomo Wolbe’s son, Rav Avraham, who today lives in Monsey).

Although he fought the extradition order for a year, Shalom Shtarkes was arrested as soon as he landed back in Israel, even though Yossele had already been found

Out of Sight [Lucerne, Switzerland]

“I didn’t even understand the significance of what I was doing. I looked at it like an amazing adventure. I didn’t dream the world was going to roil from it, or that you would suffer.”

While back in Israel, Uriel became close to Rav Avraham Meizes, a mentor of the family in Paris who had also recently immigrated. And it was through that connection that Ruth Ben-David became a key player in smuggling Yossele abroad.

Rav Meizes, who was also a close friend of Nachman Shtarkes, had drafted Uriel into the drama. It was he who realized that Ruth Ben-David, with her French Resistance background, her international know-how, and her guts, would be the ideal person for the job of getting Yossele out of the country. Both Ruth and Uriel met little Yossele in his hiding place; it was actually Uriel who had the idea to turn Yossele into a girl and take out a fake passport for “her.”

At the time, Uriel, who had been learning in Beer Yaakov, was drafted into the IDF and serving in the Intelligence Corps. “I didn’t even understand the significance of what I was doing,” Uriel tells a much older, and hopefully more forgiving, Yossi Shuchmacher at their first meeting so many years later. “I looked at it like an amazing adventure. I didn’t dream the world was going to roil from it, or that you would suffer.” The plan was that Ben David would travel to Europe and would get a visa for her “daughter Claudine.” Uriel took a picture of Yossele, which would be necessary for the plan to work.

Back in France, Ruth took his picture to a touch-up expert, and with the altered photograph, obtained a tourist visa for herself and her daughter, changing the name of the child on her papers from Claude to “Claudine.” The riskiest part of the maneuver was that she would somehow have to find a girl traveling to Israel who could stand in for this “daughter.” As luck would have it, another woman traveler, who was overloaded with children, was happy to “loan” one of her daughters to Ruth. Soon enough, Ruth was back at Lod airport, this time for an outbound flight to Switzerland together with “Claudine,” wearing a pretty hairband and patent-leather shoes.

Meanwhile, a tempest was raging in Israel. In May of 1960, after the police could find no trace of Yossele, Nachman Shtarkes was arrested. The tough old fighter didn’t say a word throughout nearly a year in a jail cell.

A National Committee for the Return of Yossele was created. Anyone who looked religious was accosted on the street to the taunts of “Where is Yossele?” And the sinister shadow of a cultural war loomed on the horizon.

In August 1961, the police raided the town of Komemiyus, but they were a year-and-a-half too late. Yossele’s uncle Shalom had brought him there in December 1959 under the name of “Srulik Chazak,” but Yossele was long gone — and so was Shalom Shtarkes, who had joined his brother Ovadia in London’s Golders Green. But that didn’t stop the Israeli police, who arrested Shlomo Zalman Kot from Komemiyus, and then demanded Shalom Shtarkes’s arrest by the British (the bris of his first child was performed in the prison where Shalom was being held). Even months after Yossele was found, Shalom, who for a year had been fighting an extradition order on charges of perjury and kidnapping, was arrested in Israel when he returned for a visit, and was finally released after being pardoned by President Zalman Shazar.

And Prime Minster Ben-Gurion would wake up every morning with the question, “Did they find Yossele yet?”

The Mossad, with its international long arm, was given the national goal of finding Yossele in one of the chareidi enclaves somewhere in the world. In Ben-Gurion’s frantic obsession, he commanded Mossad head Isser Harel to drop all other national security priorities and pull dozens of his best men off other projects in favor of locating the child. Even the hot pursuit of Nazi murderer Dr. Josef Mengele, who was located living under an assumed identity in Brazil, was stopped — the Mossad’s top resources were focused on bringing back Yossele.

Yossele’s first stop was in Lucerne, where he answered to the name Menachem Levy and was taken in by the family of Rav Moshe Soloveitchik, then rosh yeshivah in Lucerne.

It was actually there that Gittel Fuchs, who would later marry Uriel and become Ruth Ben David’s daughter-in-law, first met Yossele.

Gittel grew up in Denmark, the youngest of seven children, where her father was a shochet. After high school, her siblings were sent abroad to yeshivos and seminaries, and when she was 15, her older brother, who was living in Israel, took ill with cancer. Her parents flew to Israel to care for him (he was unfortunately niftar several months later), and she was sent to Switzerland to work as an au pair for a family who shared an apartment building with the Soloveitchiks.

In their meeting in her living room so many decades later, she reminds Yossi Shuchmacher of that summer, and although he doesn’t really remember her, he’s taken aback at her recollections.

“The Soloveitchik children were all blonde, but there was one little boy who they were fostering with dark peyos. They called him Menachem Levy,” Gittel recalls. “I heard that his mother, who they said was a righteous convert, would come to visit him from time to time. We used to play ball together — Yossi, do you remember that? Because you spoke Yiddish and I spoke German, so we would sometimes talk, although you were pretty quiet,” she says, turning to her guest.

“A year later, back in Denmark, I opened the Jewish newspaper and read the headline: ‘Yossele Has Been Found.’ Underneath was a photo of him reunited with his mother and sister. And as I recognized Menachem, the child with the sad eyes who I’d met the previous summer, my blood froze. I was so stunned and shaken that I began to cry.”

The Mossad, for their part, had set up operations in Europe, and the dragnet was picking up momentum. Ruth Ben David received instructions from Rabbi Meizes to transfer Yossele to Meaux, France, outside of Paris. Once again “Menachem Levy” became “Claudine.” He went with Ben David on the train to Geneva, from where they continued by car. The following night, they arrived at the yeshivah in Meaux, where “Menachem Levy” would spend the next seven months living a relatively normal life. He had friends and was very well taken care of and provided for. Aside for the director of the yeshivah, only two other rabbanim knew Yossele’s true identity.

Yossele spent almost two years in Switzerland and France, but as the search intensified, Ruth Ben David showed up at the boarding school in Meaux, again dressed him as “Claudine,” and flew with him to New York. There she was helped by some Satmar activists, who directed her to the Gertner family in Williamsburg, whose home was known for chesed and unmatched hachnasas orchim. The Gertners operated a small kosher mehadrin dairy, and whether or not they actively agreed, Yossele, who would be known as Yankele Frenkel, became their houseguest from March until August 1962.

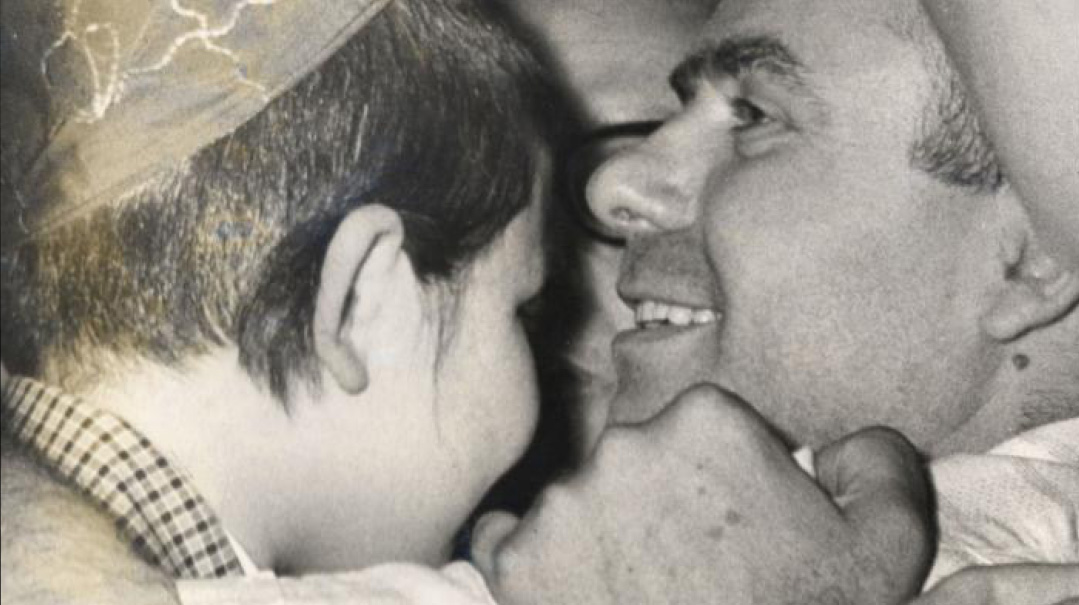

Yossele in the hands of a friendly Mossad agent, reunited with his family, and a newspaper cover with the “new” Yossele. For Mossad chief Isser Harel, every other security concern was put on hold

Hide and Seek [Mossad Interrogation Cell]

“I am guilty, I betrayed our cause. I can never forgive myself. I had a precious treasure entrusted to me, and I could not guard it.”

The Mossad had their agents all over Europe, but despite their wide web of contacts, their leads kept coming up as dead ends. Until a certain operative in Antwerp befriended a group of French Resistance Holocaust survivors who described to him the extraordinary story about a blonde, blue-eyed Frenchwoman, a Catholic, who had been part of the underground organization during the war, helping them to rescue Jews from Hitler’s grasp. The woman had converted to Judaism and became devoutly Orthodox. Her years in the underground had taught her a lot; she was smart, daring, and knew how to cover her tracks. Besides, she had an instinct for business and a keen natural intelligence. “She’s a holy woman,” the Antwerp Jews told the operative. They also told him that she had visited Israel, and that her son from her first marriage, Claude, had also converted, and after studying in yeshivos in Switzerland and Aix-les-Bains, was now in an Israeli yeshivah.

Although they didn’t know where this woman was at present, it fired up Isser Harel’s imagination and he ran with it, according to investigative journalists Michael Bar-Zohar and Nissim Mishal, who detailed “Operation Yossele” in their work Mossad: The Greatest Missions of The Israeli Secret Service. True, there was nothing specific to connect the Frenchwoman to Yossele. But she could obviously be a real asset for the Orthodox activists who needed somebody to set out on secret missions concerning Yossele. And so, Isser Harel decided to follow his very reliable intuition — the character trait that led him to the top of the Mossad in the first place — and abandon all other leads, concentrating instead on the mysterious convert, instructing his service to locate her and her son. Finding Uriel was easy. But no one knew where his mother was. Her name was originally Madeleine Ferraille; in Israel, she was called Ruth Ben-David.

The Mossad people got wind of the fact that Uriel was adventurous and might even be interested in working for them in assisting Jews trying to leave Arab countries. And so, operatives leading him to believe they had a “secret mission” for him, met togetherwith him; in reality, they were just using him to trace his mother. He reported the meeting in a letter to his mother, which he sent to three possible locations in Europe where he knew she might be. Through the letters, they tracked her whereabouts.

At the time, Ruth was trying to sell her house near Paris in order to buy an apartment in Israel. One of the Mossad agents presented himself as a potential buyer and asked to meet her in his lawyer’s office — which was actually a secret interrogation cell. Ruth, always meticulous about covering her tracks, had finally walked into their trap. But still, the game wasn’t over.

According to Gittel, the Mossad played both of them against each other. Ruth was tough as nails. She was interrogated for days and didn’t divulge a thing — and anyway at that point, she couldn’t just pull Yossele out of a hat; he was already tucked away in Williamsburg. In Israel, Uriel was then brought before GSS chief Amon Manor, who told him, “If you tell us everything you know, we promise that no legal action will be taken against you or your mother. We understand what motivated you.” Uriel was very frightened for his mother’s safety, as the punishment in France for kidnapping is severe, up to life imprisonment. He made a deal with Manor that he would tell them what he knew, provided they release his mother. Meanwhile, they told Ruth that Uriel had spilled the beans, and that he was in big trouble.

“Uriel is in our hands,” they told her. “He is facing stiff punishment. He has confessed everything. Don’t you care what happens to your son?”

At that point, Ruth knew that it was only a matter of time. Still, she’d been interrogated for days and was like a piece of iron — and standing up for her religious principles as well, demanding that someone else be in the room or that the door be opened while she was being questioned.

And Isser Harel, understanding that she was their last hope, and that she wouldn’t yield to any threats, decided to take matters into his own hands and confront her himself. He felt the only way to convince her to come clean was with moral arguments. She would never be cowed by coercion or intimidation.

“I represent the Israeli government,” Harel told her as they faced off. “Your son has told us everything, and we have a lot of other information about you. Most of your secrets are known to us. We are sorry that we had to bring you here by force… The abduction of Yossele has dealt a terrible blow to the religious community in Israel. It stirred feelings of fury against the Orthodox. You could be the cause of bloodshed and a civil war. If you don’t return the child, a blood libel may result. And just think what might happen to that child! He could get sick, even die. How could you and your accomplices face his parents then? That would haunt you for the rest of your lives.

“You are a woman and a mother,” he continued, looking her in the eye. “If someone disapproved of the way you’re bringing up your son and took him away from you, how would you feel? Could you sleep at night? We are not fighting against religion. Our only purpose is to find the child. As soon as we have him in our hands, you’ll go free, your son will go free — and Israel will be united again.”

Harel watched as Ruth’s face began to show her inner conflict. “How do I know that you are a genuine representative of the State of Israel? How can I trust you?” she asked. Without a blink, Harel pulled out his diplomatic passport, issued in his real name, and handed it to Ruth Ben-David.

“I can’t take it anymore,” she murmured. “I am going to break down . . .” Then, suddenly, she raised her head. “The child is with the Gertner family, 126 Penn Street, Brooklyn, New York. They call him Yankele.”

Isser jumped to his feet. “As soon as we get the child, you’ll be free.” He left the room.

One Motzaei Shabbos in July 1962, minutes after Havdalah, two men knocked on the door at 126 Penn Street. The men, Mossad agents, asked to see Yankele Frenkel and his immigration papers, which the Gertners didn’t have. For a few minutes Yossele protested that he didn’t know what they were talking about, but he soon capitulated.

It was there that the Mossad apprehended him and brought him back to his parents in Israel, much to the glee of a frenzied, victorious media. July 4, 1962 wasn’t only Independence Day in the US. It was a victory day for many Israelis as well.

Yet while Israelis were rejoicing over the return of Yossele to his parents, Ruth Ben-David felt broken and vanquished. “I am guilty,” she later wrote in an out-of-print autobiography. “I betrayed our cause. I can never forgive myself. I had a precious treasure entrusted to me, and I could not keep it.”

Still, Madeleine Ferraille/Ruth Ben-David had so admirably demonstrated all the qualities necessary for a secret agent that Isser Harel himself offered her a job with the Mossad. But he was too late. Ruth returned to Jerusalem and vanished into chareidi world, where three years later, she would marry Rav Amram Blau, the 72-year-old leader of Neturei Karta.

“Today,” says Gittel Ben David, “we look at this story and we think, ‘how could both sides have made such a mess?’ But my mother-in-law was motivated purely by her idealism. She risked her life for it.”

Rav Yitzchak Yedidya Frankel, expert peacemaker, and his son-in-law Rav Yisrael Meir Lau. “He was sure he’d be able to settle this incident and find a way to guarantee Yossele’s future”

Missed Chances [Rechavia, Jerusalem]

“Suddenly I found myself surrounded by a group of secular teenagers. They began chanting ‘Where is Yossele,’ whipped out scissors, and cut off my peyos.”

But modern Israeli history could have been written differently. Even before the saga was over, many Torah personalities had begun calling on the powers involved to return Yossele to his parents. In fact, Nachman Shtarkes had also agreed, and in a meeting with Israel’s most prominent rabbanim, even signed a compromise agreement. The only problem was, it was too late. He too had lost control over the child’s location.

The initiator of the meeting was former Israeli chief rabbi Rav Yisrael Meir Lau, who remembers the hatred and animosity he experienced as an obvious-looking representative of the Torah-observant community. One day he arrived to speak at a municipal high school before one of the Jewish holidays and the students were waiting to ambush him by the gate, shouting “Where’s Yossele?”

Historian Rabbi Yisrael Gellis remembers those battles well. “I paid for it with my two peyos,” he says. “I was traveling on a train, when suddenly I found myself surrounded by a group of secular teenagers. They began chanting ‘Where is Yossele,’ whipped out scissors, and cut off my peyos.”

“By this time, rabbanim across the spectrum realized something had to change. And my father-in-law, Rav Yitzchak Yedidya Frankel, was a well-known peacemaker and reconciliations to many disputes were reached through his arbitration,” Rav Lau told Mishpacha. “He believed he would be able to settle this incident and to find a way to guarantee that Yossele’s future included a Torah education without severing ties with his parents. Yossele’s parents were inclined to accept the proposal. They understood that they didn’t have too many options and believed that this could solve their problem.”

The one who had not yet agreed was the grandfather, Reb Nachman Shtarkes, who did not recognize the state rabbinate. It was necessary to gain his trust and convince him that the intentions were sincere.

The meeting took place in the Rechavia home of Reb Yitzchak and Bluma Weil, whose shoe store on Jaffa Road was for years an iconic Jerusalem landmark. They were upstanding Yidden, respected by all the Orthodox camps, were used to opening their home to guests of all types, and agreed to host the meeting and to keep it in total secrecy — which, given the press’s nose for news, ended up being a futile endeavor.

Still, when the parties arrived, the journalists had to make do with waiting outside, although when Ida walked in, before heading into an inner room where the meeting was taking place, she first turned to the big living room window that faced the street as the cameras clicked away. Ida joined the discussion beside her husband Alter, as the sides began to weigh the options. Each side unloaded what was on his heart and Rav Frankel tried to find common ground between the expectations and hopes of both sides. After several hours, Rav Frankel emerged with a satisfied smile. Both sides seemed very calm.

Under the agreement that was reached, both the parents and grandfather would cooperate in the child’s upbringing. And, as previously agreed, the child would receive an uncompromised Torah education without losing ties with his parents. The meeting could have gone down in history as the one that changed the future of the chareidi community, while the family dispute would become a thing of the past. But the agreement was never implemented — because by that time Reb Nachman could not locate his grandson and didn’t even know whom to ask to give him back. He had totally lost control over Yossele’s location, and there were likely certain people involved in the operation who tried to prevent Reb Nachman from obtaining accurate information so that he wouldn’t implement the compromise plan.

The house looks different today, but the address, 126 Penn Street, hasn’t changed. According to Reb Dov Gertner, the Satmar Rebbe thought the whole thing was a big mistake

Back in Time [Williamsburg, New York]

“I’m not discounting the possibility that they simply came and dumped Yossele on my father with instructions to hide him. But I followed instructions – I learned Gemara and Chumash with him, and even taught him to play chess.”

Yosele was reunited with his family and years went by. The excitement died down and Yossi Shuchmacher grew up, served in the army, got married, raised a family, moved to Shaarei Tikvah, and became a business consultant. Isser Harel and Yossele Schuchmacher actually met once, nine years later, at a party thrown for the publication of a book on the Mossad. Yossele, who was then a private first class in a tank division, shook hands with Harel and told the crowd, “Isser Harel has been the most important person in my life. Without him I would not be here among you.”

And then, in 2007, on a trip to the US with his wife, Yossi Shuchmacher had a reunion he’d been hesitating about for years: He met a then-elderly Mrs. Gertner and some of her children, who he remembered from those few complicated months in the summer of 1962.

“I’ll never forget them,” he confided later to Mishpacha’s Eliezer Shulman, with whom he agreed to take a walk in “old neighborhood” of Meah Shearim, where they were joined by one of the Gertner’s sons, Reb Dov Gertner. “The oldest daughter, Freida, who took it upon herself as a personal project to protect me, and all the rest of the children… and Mrs. Gertner, who ran her empire with quiet nobility side by side her huge hachnasat orchim. But you know, every time guests would come in, I’d have to hide in the attic. But I didn’t mind. I was a small child, I was told my spiritual life was in danger, and I happily cooperated. I didn’t have a normal childhood, but looking back, I can’t say it was terrible. I was surrounded by loving people – the Kots, the Soloveitchiks, the Gertners – in a way, it was like one long camp.”

He said that if there was one thing he could tell Mrs. Gertner a”h today, it was that he understood her, that he holds nothing against her. That he realizes that, although he doesn’t agree with what was done, she was acting out of her emunah and her principles. Still, he said, back then, after returning to his parents, he felt hurt and betrayed.

“It took years to get over it,” he said. “They told me my parents returned to Russia and left me alone. But I’ve made my peace. Years have passed. Today I understand that this wasn’t about me personally. It was about the terrible split in our society. Each sector went too far. The chareidim went too far when they separated me from my parents, and the secular went overboard with their violent obsession. Ben-Gurion got the entire security apparatus on the case, without any proportion or consideration for other burning security issues.”

Shuchmacher said he didn’t have contact with his grandfather after returning to Eretz Yisrael, as Reb Nachman by that time was already very ill. But, he clarifies to dispel any inaccuracies, “my parents had a very close relationship with him. They even supported him financially. I don’t think they were really angry with him, even though they fought to get me back in court. They weren’t antireligious. They knew that Zeide was giving me a chareidi education. Then, when my father came to take me back, for some reason he thought that they intended to go back to Russia. Maybe because of the hardships. Maybe because my father was still an ardent Communist. Whatever the reason, Zeide was frightened, and fought to keep me. But you should know that my parents never intended to go back. I’ve checked that out thoroughly. Yet by the time Zeide realized it, he’d already lost control of the situation and others entered the picture, taking it upon themselves to hide me from my parents.”

Dov Gertner was already in yeshivah when Yossele joined his family, so he wasn’t home that much. But he does remember the day Yossele moved in.

“My parents had a large home that was always open to guests,” he told Mishpacha. “Everyone knew they could get a meal there, and to this day I can’t understand where my parents had the funds to feed all those people. One day my father called me over and told me we have a boy staying with us, and that I should learn Torah with him. At that point, the papers were full of ‘Yossele’ so I immediately understood who this boy was. I’m not sure that my father was ever really consulted whether he was willing to hide the boy. Our home was open, and I’m not discounting the possibility that they simply came and dumped Yossele on my father with instructions to hide him. But I followed instructions — I learned Gemara and Chumash with him, and even taught him to play chess.”

The Satmar Rebbe became involved, but Reb Dov Gertner remembers that controversially. “After Yossele was taken away, my father was brought in for questioning by the U.S. Department of Immigration. He disappeared for two days, and we suspected that he was kidnapped by the Zionists. We approached the Satmar Rebbe, and to this day I remember his outburst. ‘Why did he get involved in this in the first place?!’ The Rebbe was livid. ‘Now that everything is a mess, you come to ask me for help?’ From his reaction, it seemed obvious that he thought the whole thing was a big mistake. Still, the Rebbe activated his contacts and discovered that my father wasn’t kidnapped, but rather arrested by the US authorities. A few hours later he returned home. The Israeli authorities also wanted my father to stand trial. There was an official petition for his extradition. In the end, it was dropped because of political considerations.”

Time to Heal

“There was a journalist who tried to arrange a meeting between us. I insisted that she state that she regretted what she had done, but she refused.”

Yossi Shuchmacher has come full circle. He shook hands with Isser Harel. He reconciled with the Gertners. He forgave his zeide. And now, he’s drinking coffee with Uriel Davidson, the young yeshivah student who took his fake passport picture and even dyed his hair.

And then, Yossi’s eyes catch two pictures on the wall. The first is of a venerable looking Jew. The leader of Neturei Karta in Jerusalem, Rav Amram Blau. Beside him is a photo of the woman who eventually became his wife, Ruth Ben-David. “That’s her,” he says. “She’s the one who kidnapped me. I have no idea how she dared do it.”

Perhaps this is an opportunity to apologize and express regret in her name?

“There was a journalist who tried to arrange a meeting between us,” Shuchmacher says. “I insisted that she state that she regretted what she had done, but she refused.”

“The Maariv newspaper arranged a meeting between the two of them a few years ago, before her stroke — she died the following year,” says Gittel, who has a bit of a different take. “But she was very upset by it. She felt it was a set-up in which she’d be forced to ask Yossele for an apology, sort of a public apology for the chareidim. She wanted no part of it. At the time, she acted with pure motives.”

Ruth Ben David died 22 years ago. Maybe now, things look different? “Over the years I have met dozens of people who were partners to the story,” says Yossi Shuchmacher, “And I’ve come to terms with all of them. I understood them all. She’s the only one I never reconciled with.”

Perhaps the time has come.

Uriel being escorted to his chuppah by Rav Amram Blau, his mother’s new husband. “He was always kind to me, and later treated my children like his own grandchildren”

Guardian of the City

A year after Yossele was found by the Mossad and reunited with his parents, Ruth Ben-David was back in Israel. Her son Uriel was actually the one who thought of a surprising match — a shidduch between his mother and the recently widowed Neturei Karta firebrand Rav Amram Blau.

Rav Amram Blau, stauch anti-Zionist, honored Torah scholar, fearless government protester, and one of the most prominent members of Jerusalem’s Old Yishuv, had been widowed two years previously. He was a grandfather many times over, but the age difference nothwithstanding — he was over 70, she was 45 — the two met, found favor with each other, and an engagement agreement was drawn up.

“In Rav Amram, she saw a tzaddik, and that was the highest level she could attain,” says her daughter-in-law Gittel Davidson. “And she wasn’t afraid of it, even if it meant totally changing the parameters of her life.”

However, it was a marriage that almost wasn’t. Many in the community were outraged. A giyores is fine for secret missions, but to marry Rav Amram Blau? Even the Eidah HaChareidis called on Rav Amram to cancel the engagement, determining the amount to pay Ruth for the broken contract. But Rav Blau had made his decision.

Still, the protests grew so volatile that when the couple did marry a year later, they had to leave Jerusalem, the city Rav Blau had never before left. The marriage ceremony took place on September 2, 1965, at 12:15 a.m. in Bnei Brak, where the couple resided for several years until the storm subsided. Rav Amram Blau passed away in 1974.

“They had an active life together and had tremendous respect for each other,” says Gittel. “And they always had an interesting array of guests at their meals. It’s true, Rav Amram Blau was tough when it came to his beliefs, but he loved all Jews and would do anything to try to bring them closer, without regard for his personal safety or honor.”

Because he was so staunchly against the State, he refused to benefit from it, even indirectly. “He never used public transportation, and wouldn’t touch Israeli currency,” Gittel remembers. “Instead, he created his own voucher system that he would use to barter goods. My mother-in-law respected this. She thought like him, identified with him. But she was also involved in major fundraising for all her projects. So she kept her Israeli currency in a post office box. She would never oppose him by bringing it into the house.”

When Gittel was 15 and met Ruth the summer she worked as an au pair in Lucerne, she never imagined she would see the “mother” of “Menachem Levy” again. But in 1965 their paths were to cross permanently.

“After the news of their marriage leaked, my father came home from shul and said, ‘There is a huge scandal brewing in Eretz Yisrael. Rav Amram Blau married a convert…’ Somehow I had a feeling that I would be connected to this story. A week later I was on my way to Eretz Yisrael, to spend Tishrei with my siblings who were living there. Someone proposed the shidduch with Uriel. We were to meet on Succos in the Blau’s home in Bnei Brak. This was my first shidduch and I was absolutely petrified as I walked into their succah. I was sure Rav Blau wouldn’t look at me, or that he would be hostile. But in fact, he was so warm to me, he smiled, made me feel welcome and at ease. He was always kind to me, and later treated my children like his own grandchildren. He even spoke to them in Hebrew, a language he was ideologically opposed to.”

It is known that even after her marriage, and in fact until she was in her seventies, Ruth Blau continued her missions through Europe and even to hostile Arab countries in search of Jews in trouble. Some speculated that she worked for the Mossad, the very institution that was her nemesis in the early 1960s.

“Nonsense,” says Gittel. “She would never work for them, although I’m sure they benefited from her private work.”

The case that was literally her obsession for over 20 years was that of Moishele Shimon, a three-year-old who disappeared on Rosh Hashanah of 1951. The army and police spent months searching for him, and over the years, the family, Satmar chassidim who’d immigrated from Hungary, picked up enough information to believe that he was kidnapped by missionaries and taken out of the country. Ruth combed all the monasteries and abbeys in Israel, and came upon a lead that would take her to Jordan, England, and back to her native France. In each country she discovered children (now adults) who had been taken away from their families. But she never was able to find Moishele.

Ruth also traveled extensively in her attempt to locate missing soldiers Zachariah Baumel, Yehuda Katz, and Tzvi Feldman, who were captured in the battle of Sultan Yacoub in the 1982 Lebanon War. After the war, she went to Lebanon to look for them, using contacts that would make any spy proud. She also met with Yasser Arafat in the 1990s regarding the MIAs — her link to him was his mother-in-law, Palestinian militant Raymonda Tawil, whom Ruth had met in Europe.

In 1993, Ruth made her way into Iran in an attempt to speak to Ayatollah Khomeini about the arrest and death sentence of a leader of the Jewish community, Feysollah Mechubad. Mechubad, 77, served as the gabbai of the Tehran synagogue and was active in raising funds for the poor, while Iranian authorities claimed he was an Israeli spy. Ruth went to plead on his behalf, and although she didn’t see Khomeini, she did have an audience with his secretary, who promised her they would commute his sentence. After she left Iran, he was tortured and executed.

Although her missions were not fruitful in the technical sense, she was always willing to take risks if it came to the possibility of saving Jewish lives. Her phone book contained the private numbers of many Palestinian terror leaders and other influential figures in the Arab world.

“After Rav Amram died, she continued to live in Meah Shearim and was known as the address for the indigent — for widows and orphans and the elderly,” says Gittel. “She was staunchly anti-Zionist and definitely meshed with the surrounding ideology, but I don’t think she ever really felt like she fit in. She was university educated, worldly, politically astute, and fearless. And she had friends all over the world.

“She raised millions, but she didn’t keep anything for herself — she owned one Shabbos dress. I don’t know where she got her strength, especially in her later years. She was fundraising in London, at 79, when she had the stroke that led to her death.”

Ruth Blau spent the last year of her life in London’s Schonfeld Square Home, where she passed away in 2000 at age 80.

— with reporting by Aharon Kliger and Yisrael Groweiss

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 913)

Oops! We could not locate your form.