The Debate

“So, the religious guy who was meant to debate the issue with us didn’t show up. Could you speak in his place?"

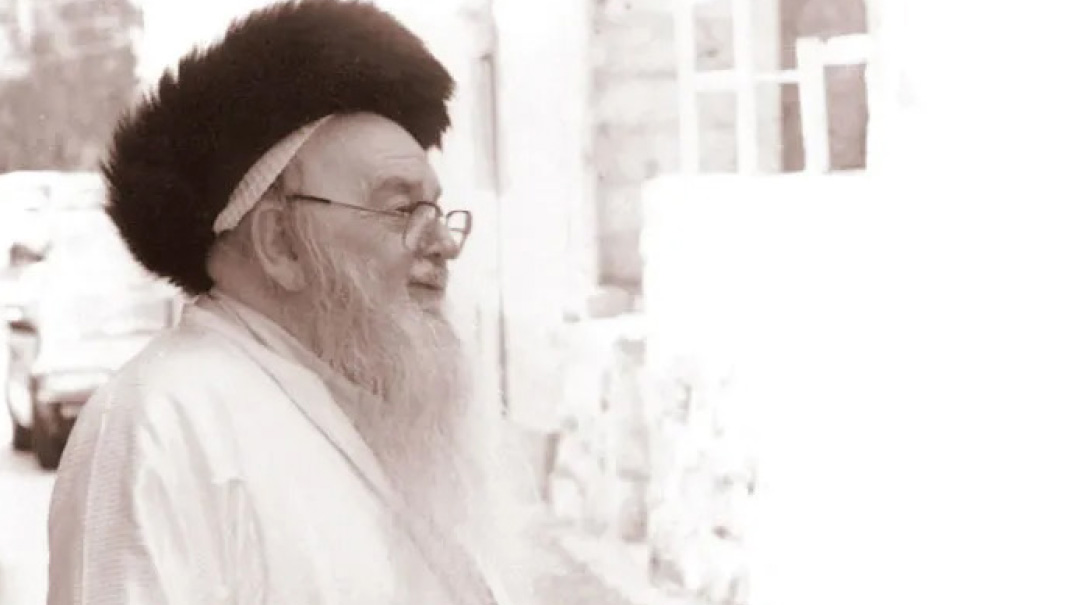

As told to Rivka Streicher by Rabbi Y. S. Fried

In the summer of 1977, I came to Israel for the summer for a skin-healing regimen at the Dead Sea.

My wife and I stayed in Arad, the closest community with a minyan. This was in the days before it had a large chareidi population, before it was even a proper city.

One day, we drove some miles into the huge Tel Arad National Park, and settled ourselves on a pair of sun loungers. The wind swirled sand, and a shimmering haze formed in the distance. Aside from a lonely bar, there seemed to be no one around for miles… when out of the mist, a pack of youths sauntered over. They were from a nearby kibbutz, tough Hashomer Hatzair’niks.

They saw me, with my beard and chassidish clothing, and they started muttering. “Begin’s people. Soon we’re all going to have to look like him….”

Menachem Begin was Israel’s new prime minister. His victory had ended three decades of Israeli Labor Party dominance. These were new times. El Al had stopped flying on Shabbos. Begin was not afraid to say phrases like baruch Hashem or b’ezrat Hashem on TV.

They approached me, these youths, and one of them, the leader of sorts, said, “Listen, can you do us a favor? We were going to have a discussion about the new situation, about the kefiah datit [religious coercion] going on in this country. But we want it to be a fair discussion, you know. We’re liberals, we’re open-minded….”

I snorted. So open-minded, their minds were literally falling out.

“So, the religious guy who was meant to debate the issue with us didn’t show up. Could you speak in his place? We’re going to the pub, to debate this like men.”

“We can debate it like men, right over here. I’m not going to a pub.”

They nodded. They respected at least that.

More young people were rocking up, sweaty, swarthy youths.

My wife turned to me and said, “Seriously? What are you going to say to them?” She thrust out a hand, indicating their clothes, their manner, as if anything I said could make a difference.

“Hashem’s sending me an opportunity. I have to try,” I said, and she just shook her head, resigned. She knew I wasn’t one to let opportunities pass by.

As their spokesperson stood up and cleared his throat, I murmured a tefillah.

He started with a touch of drama. “The issue at hand: We live here in a democratic land. How can they force religion on us?”

I stood up, looked the guy in the eye. “First of all, no one’s forcing anything. This is a democracy. You, the majority, chose Begin. If you don’t like how it is, you can leave.”

“What do you mean? It’s our land, our inheritance.”

“Oh, really? Where are your parents from?”

“Iraq.”

“Iran.”

“Poland.”

“So, what inheritance are you talking about?”

“You know, Avraham, Yitzchak, Yaakov…”

“We’re talking Avraham, Yitzchak, Yaakov, are we? So, you do identify as descendants. You’re talking Torah. Okay, let’s talk Torah.”

“Round one,” someone called out.

I breathed out.

But then another guy stood up. “Talk Torah? Torah is just one restriction after another….”

I picked up a small stone and pointed to the small building that housed the bar. “If I take this stone and throw it in through that window, what will they do?”

“They’ll call the police. They’ll arrest you.”

“So, where’s my freedom? I’m restricted. I can’t do what I want.”

“No, no, that’s not—”

“Or road signs,” I say. “You have to stop, give right of way, don’t park here, no left turn. But you understand that road signs are not restrictions to freedom, right? They’re rules that keep you from hurting yourself, from falling off cliffs.”

They nodded, if a bit reluctantly.

“It’s the same with the Torah. It’s not about restricting us as much as saving us from hurting ourselves, or hurting others.”

And before I could exhale, a young man in an orange T-shirt burst out, “But why do you need to look so different? Why can’t you blend in?”

I explained that when we have so much going for us and we look just like them — just as cultured, just as well-dressed, just as interested in the same pursuits — that’s what gets the ire, the jealousy of the nations coming to the fore. That this is why the Enlightenment was followed by the Holocaust.

We went on for two hours, those youths and I. Volleying back and forth. The sun sank in the sky, their figures grew long shadows, their expressions started to mellow in the shade. Maybe, maybe, something I said had gotten through to them.

But inside me an urgency grew; it was almost evening, the discussion was almost over, and then what?

I started to yell and scream, “Kol Yisrael areivim zeh l’zeh, this is what I vowed, I’m responsible for all of you! And if that’s so, I’m telling you this: You know the truth! It’s staring you in the face. Don’t turn away from it.”

I felt the intensity of what I was saying; muscles bulged in my neck. They were quiet, the group. Thinking, hearing. At least they respected my show of caring.

Or did they?

“What if I just don’t believe?” someone dared to say.

I was shaking by then. I cared; I cared so badly, I was going to say it like it is.

“What do they call you?” I asked. He started to answer, at the same time I exclaimed, “Aristotle? You’re what,20? How could you have learned everything, anything? It’s not that you don’t believe, you just haven’t learned, and you’re trying to silence your conscience.”

The youth was stunned into silence, there was a smattering of applause, and they clapped faster, stronger. That night in the desert, I got a full-out standing ovation.

We went back to America. I told some people about what happened that evening. I’d like to think I did something, that I peeled away just a layer of their sinas haTorah, their sinas chareidim… but who knows?

And then a handful of years later, a religious man came over to me one day in shul.

“I was part of that group, of that debate. We all had our duties on the moshav and I was the shomer lailah that night. I heard you out, felt your passion. I stood and guarded the camp and thought about what you’d said, all night.”

I took his hand, took hold of his tzitzis with my other hand, and wept.

Rabbi Yechiel Shmuel Fried is a longtime shochet and writer in Hebrew and Yiddish. He lives in Spring Valley, New York.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 869)

Oops! We could not locate your form.