Calculate the Cost

W

hen a young man leaves the shelter of yeshivah for a job or business enterprise, he discovers two new worlds: one outside, and

one within.

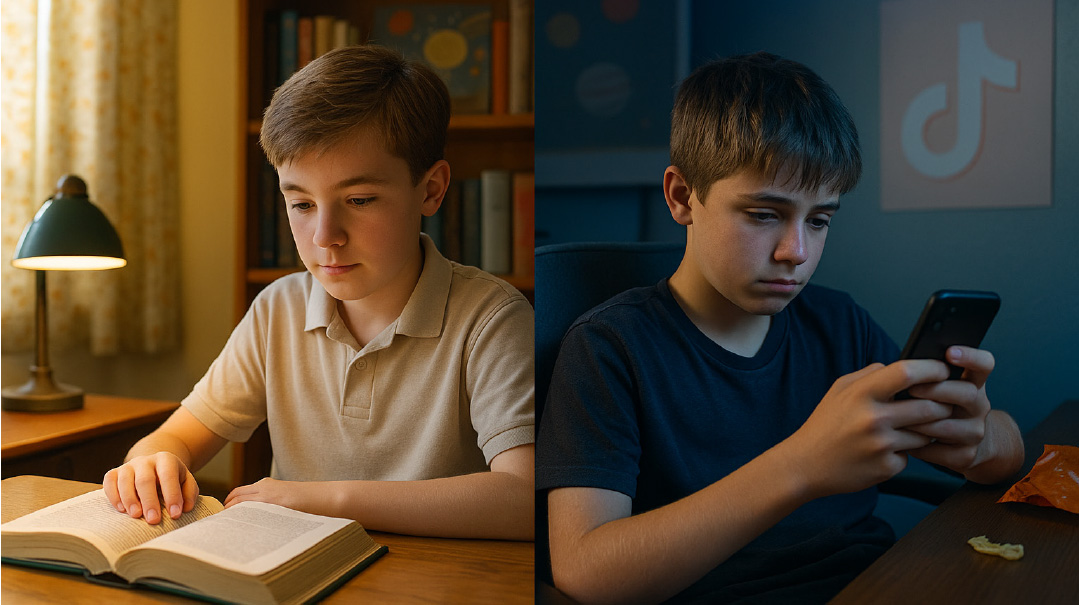

A yeshivah bochur today leads a life that is largely cut off from the outside world. When he enters the workforce, he not only discovers that there is a world out there, but also that it can be interesting, challenging, and full of opportunities. As he starts bringing in money and tapping talents and skills he barely knew he possessed, he finds this new world increasingly compelling. As his potential unfolds, and he discovers that he can be creative, enterprising, responsible, and all sorts of attributes that may not have found expression while he was in yeshivah, he begins to experience life in a new way. And he finds himself in need of new spiritual tools, as well.

Of course, the fact that the outside world is fraught with nisyonos different from the ones he faced in yeshivah isn’t exactly breaking news. Back during his yeshivah days he knew, in theory, about the broad range of possibilities out there, and he may already have grappled with their distracting allure. But there is an essential difference between dealing with these same nisyonos as a yeshivah bochur and dealing with them now, as a man who is out in the world.

You might compare it to the difference between the attraction wielded by worldly comforts to an average person versus a person of means. Both these people have the same desires, and those desires may get in the way of their avodas Hashem. But the average man can’t just reach out and procure whatever he wants from the world; his financial status is a firm impediment, a filter that blocks him from fulfilling every random whim or desire. This doesn’t mean he has no nisayon. The desire still exists. But for the most part, it remains in the realm of fantasy.

A man of means, on the other hand, can turn his wishes into reality with the swipe of a credit card. Desires flitting through his mind are not all he has to deal with; all sorts of comforts, luxuries, and opportunities are actually there, waiting to be transformed into reality at his beck and call.

Likewise, the transition from the yeshivah world to a secular field of endeavor brings a young man’s nisayon from the realm of imagination to the realm of solid reality — and it may catch him inadequately prepared. It follows, then, that if we want to equip our young men with coping tools for the nisyonos of the outside world, we need to habituate them to overcoming difficulties that are actual and not just theoretical.

We needn’t look too far to find places like that in a yeshivah bochur’s life. Yeshivah bochurim face real-life struggles in all areas of their sheltered existence. For one, the main struggle is in learning, for others, it might be in tefillah, complying with halachah, or in middos. The problem is that when we come up against a challenge like that, we tend to see it as an obstacle in our path, something that we have to push our way past or through. And we think that the way to do that is to ignore the challenge, close our eyes, bite our lips, and concentrate on doing what we’re supposed to do.

Chazal don’t think so. When they teach us how to find the right path for our personal avodah, they tell us to make a calculation: “Always calculate the cost of a mitzvah against its reward.” The “cost” of a mitzvah is the price I have to pay for it in terms of exertion, money, or any difficulty involved in fulfilling it. One bochur finds it hard to get up in time for davening, another finds no enjoyment in learning. Everyone encounters some sort of difficulty in his avodas Hashem. And all these things should be considered in our personal calculations.

We are generally in the habit of looking only at the sechar mitzvah, usually in terms of how much the mitzvah can elevate us, how worthwhile it is for us spiritually. But Chazal tell us that we should give equal consideration to the other side: What price must I pay to fulfill this mitzvah? What does it demand of me, and at what point do I feel myself resisting? What is it that I think I’m losing, as it were, by putting aside my own wishes and doing ratzon Hashem?

By answering these questions, we can learn a lot about ourselves and about our personal pathways to avodas Hashem. If we instead try to ignore the difficulty, grit our teeth, and push on, we miss our chance to discover new, unrecognized abilities within ourselves.

When we find that something is hard for us, we are standing at a crossroads. Listening to the voice inside that’s saying “This is hard,” instead of repressing it, can help us choose the best way to go forward.

To do this in a healthy way, we need to relate to the challenge like a doctor diagnosing an illness or performing an operation, cool and unafraid. Let the “patient” inside us talk about what’s bothering him, and let us listen with interest in order to decide on the right approach to treatment.

For example, let’s take a bochur in a yeshivah where the typical approach to learning is that the boys sit and prepare written summaries of the shiur they’ve heard as a form of review. While most of the bochurim manage fairly well with this method of learning, this particular boy feels something in him resisting it, and it seems to be growing worse every time he sits down to summarize. Learning is becoming a tiresome burden, and he is losing interest in it.

If this boy views his resistance to summarizing as a bother, and thinks the way forward involves gritting his teeth and ignoring his resistance, then he’s also subliminally viewing himself as a rebellious type who doesn’t want to sit and learn. Even if he succeeds in forcibly overcoming his inner resistance and doing what the yeshivah expects of him, he loses his chance to develop his learning ability in the best possible way.

If, on the other hand, he focuses on his resistance and relates to it in an analytical manner, he might find out many truly useful things about himself. He may come to realize that summarizing isn’t his strong point, and he may be prompted to find a method of review that better suits his personal abilities. This approach will actually build him up and allow him to discover heretofore unknown potential.

The same method can be utilized by each person who goes out into the world of secular endeavor. The difficulties we encounter in our avodah, whether in yeshivah or in the outside world, needn’t be treated as hurdles to power through or a sorry fate that we have to bear forever.

By realizing the potential inherent in our challenges, we can use them as guideposts on our personal path in the service of Hashem, as keen indicators of our unique internal makeup, and keys to personal growth. —

Rav Reuven Leuchter, a primary disciple of Rav Shlomo Wolbe ztz"l, is among the leading mussar personalities in Eretz Yisrael today, with his worldwide network of shiurim and teleconferences. He is the author of Meshivas Nefesh on the Nefesh HaChaim, an annotated commentary on Rav Yisrael Salanter’s Ohr Yisrael, The Pesach Hagaddah, and the soon-to-be-released Living Our History.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 750)

Oops! We could not locate your form.