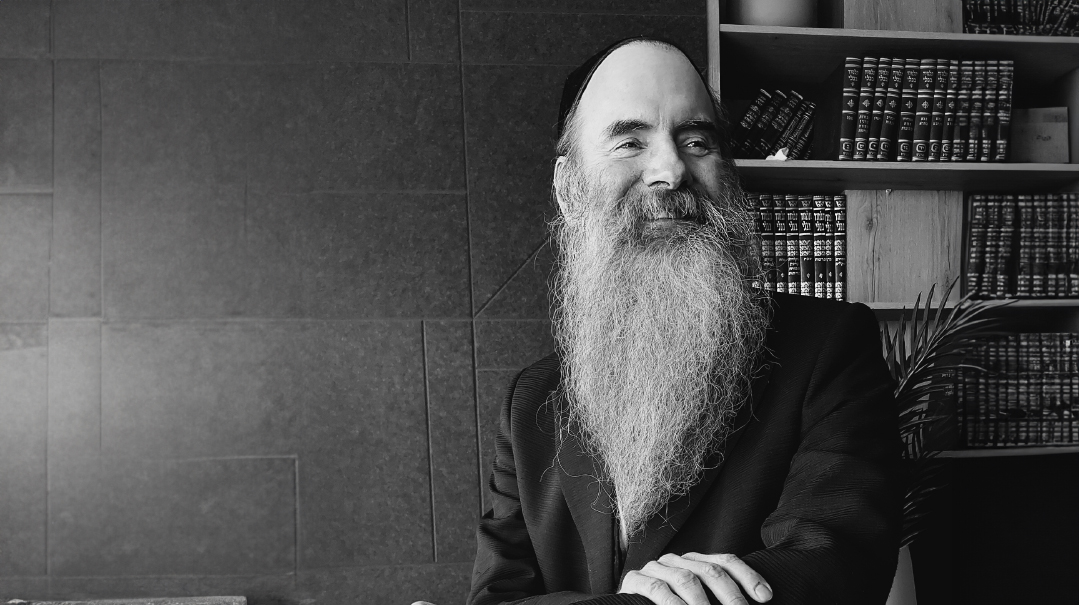

20 questions for… Refoel Pride

| July 30, 2024“It’s going on 15 years, which is surreal. In a previous life, I was a municipal budget analyst for 13 years”

Refoel Pride joined the staff of Mishpacha in 2009 as a proofreader and now serves as an editor, writer, and chief copy editor — in which role he supervises the proofreading department in Jerusalem. For him it’s the family trade — both his parents had journalism degrees, his wife is a senior editor at Gefen Publishing, and two of his sons work as translators. During working hours, a cup of black coffee can usually be found within his arm’s reach.

My ideal work environment

A private office with a door that closes and a great view. Also, air conditioning cold enough to allow storage of sides of beef. Mishpacha provides two out of three, which ain’t bad.

Deadlines make me…

Focused.

I learned the most from writing about

A tribute to the Hornosteipler Rebbe of Denver, Rav B.C. Shloime Twerski ztzvk”l. The first feature I wrote for the magazine. It was life-changing.

The accomplishment I’m proudest of

When I look back on my “accomplishments,” I find that I was not the One Who did the heavy lifting.

The best piece of advice I got

My rebbe once told me that because Hashem Himself gives parnassah, and does not delegate it to any other shaliach, you can look on your employment situation as a direct expression of His will.

1

How many years are you at Mishpacha, and what did you do before that?

It’s going on 15 years, which is surreal. In a previous life, I was a municipal budget analyst for 13 years. That was also a fascinating job.

2

What was the biggest mistake that slipped through, or a near fiasco corrected at the last minute?

We’ve had some truly painful mistakes get by — like the profile of a well-known askan with a tricky last name that we all worked so hard on, only to have a last-minute technical glitch cause a misspelling. In a huge font. I still feel awful about that.

Near fiascos getting corrected at the last minute are all in a day’s work for us.

Here’s a mistake that would’ve been really hard to avoid. This touches on an arcane rule of grammar. For a Yom Tov supplement about ten years ago, we profiled a group of Gateshead women who ran a wedding gemach. The writer included the following sentence:

The service — provided at cost price — is all-encompassing, including everything needed for the dinner (bar hall, musician and photographer) from waiters, linen, tableware and flowers to mirrors, candles and ice buckets.

Take a look at that phrase in parentheses. What is the word “bar” doing there? Well, the proofreader (an American) thought this was a list of things you’d find at a wedding, and innocently inserted a comma after the “bar.”

Unfortunately, the writer, who was born in the UK, had another meaning in mind — namely, the preposition “bar,” which in the King’s English means “except for.” (In American English, this usage occurs only in the phrase “bar none,” and rarely appears otherwise.) The writer definitely did not mean that this Gateshead wedding gemach provided low-cost alcohol.

That’s one of the challenges of providing content for a global audience with a global staff.

3

How many times is an article proofread? Tell us about the process.

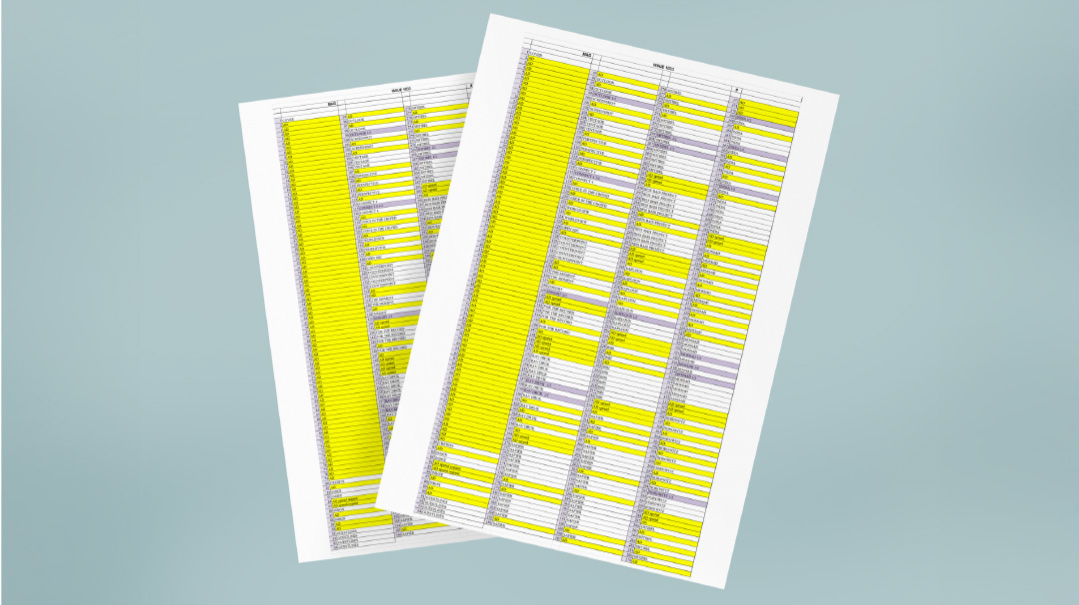

The proofreading department sees every article twice. The first time is right after the editor finishes working on the writer’s submission. We try to catch any stray errors in spelling, punctuation, or grammar. We also check all transliterations of non-English words against our style guide.

The second review comes at the layout stage, when the graphics team has worked up a design for the article. They print out a proof, which is a hard copy of the typeset text. (Hence the term “proofreading.”) It looks very similar to the final product you’re holding now.

At this stage, we’re still trying to catch any last mistakes, but we’re also checking graphic elements like indents, fonts, pull quotes, and photo captions. We still check the text on paper, because errors somehow tend to jump out more with printed text than they do on screen.

We try to make sure each article is seen by a different proofreader at each stage. In the old days, magazines employed enough proofreaders to review every piece half a dozen times. Those multiple layers help catch the most typos.

4

How long is a typical proofreader’s shift, and why?

We try not to extend shifts past six hours. The work is very intense. A proofreader is checking every word, every comma, sometimes reading the text aloud (very softly, so as not to disturb coworkers). Six hours is the outside limit for effectiveness. After that, the letters start to swim on the page.

5

Where does a proofreader’s job begin and end?

A proofreader is expected to correct the basic errors described on the facing page. Where it gets a little tricky is on questions of word choice or awkward phrasing. Those fall outside the proofreaders’ purview, but we do want them to notice such things, and to suggest improvements to the editor.

When does a proofreader’s job end? I can’t honestly say. Never?

All I know is that since I started this job, reading as a pastime is ruined for me.

6

Do you fact-check dates, names, locations?

We always check spellings of names, places, titles, and the like. For things like dates and locations, we might check Google or Wikipedia. But we’re working under deadline, so we simply don’t have time to conduct extensive research. (Even before a proofreader gets a piece, it has been copyedited by an editor who takes pains to check all facts, so this is just an extra layer of caution.)

7

What is your relationship with the writer and with the editor? Who has final say?

There’s a give and take. The editor is the final arbiter, but the writer and the proofreader can each make a case. If we’re going for a certain flavor in an article, some proofreading rules might be waived. But color has its limits. Ultimately, we’re here to help the reader.

8

How do you motivate your team to pay full attention throughout the busy Yom Tov periods when there is so much content to be checked, and so much housework waiting for them at home?

I can’t claim any credit for that. Our staff is so professional, so dedicated, so self-motivated, so positive — consummate team players. I’m as amazed as you are. We hire the best people.

9

Tell us about the style guide. How was it built, why is it needed, who updates it, and how often is it consulted?

The Mishpacha style guide was originally developed by Mrs. Yocheved Krems Frischman, the pioneer of our proofreading department. It has kept the same basic framework all along, although there have been countless additions.

Everyone in publishing maintains a style guide. It’s a way of keeping the content consistent and recognizable — part of the “brand identity,” I guess you could say.

We maintain it online and update it in real time. Mishpacha proofreaders around the globe, in the Tristate area or in Jerusalem, are able to check it around the clock. I’m pretty familiar with it, but I still consult it at least hourly.

10

Why do some Hebrew or Yiddish words get italics while others don’t?

If a word is in the online Merriam-Webster’s dictionary, it’s considered an English word, and we don’t italicize it. Terms like “schlep,” “schmooze,” and “mensch” are of course listed there, but some less obvious ones are “niggun,” “mashgiach,” and “oneg Shabbos.” We check the site often and are sometimes amazed at what we find.

Once, a proofreader called out to me, “Mr. Pride, look!”

There on her screen was the Merriam-Webster entry for “yetzer hara.”

11

If you could change one illogical feature of the English language, what would it be?

This isn’t a feature of the English language per se, but I would change the American practice of always putting periods and commas inside quotation marks, and instead align it with the international standard. Americans are the only ones who do it that way, and there’s no logical basis. I’m as for the Stars and Stripes, Mom, and apple pie as anyone, but it gets annoying.

12

What do you look for when hiring a proofreader?

On paper, any germane experience — writing, editing, or proofreading. Beyond that, we’re looking for a perfectionist streak, a love of reading, ability to work well on a team under pressure. And of course, being a Mishpacha fan helps.

13

Do you really think commas make a difference to readers?

To most readers, probably not. But a comma, or the lack of one, can completely change the meaning of sentence. Back at the 1988 Republican convention, a debate broke out in the platform-drafting committee over the wording, “The party opposes any tax increases which harm the economy.” Conservatives demanded that a comma be inserted before “which.” It turned into a real row.

14

What is the most discerning compliment you ever got?

I’ve gotten nice compliments for my writing and for my editing. No one ever compliments a proofreader. Our whole job is to find mistakes. When one gets through, we take it hard, because we’re perfectionists. But that’s what people tend to zero in on.

So let me use this platform to address the Mishpacha proofreading staff: I field all your incisive questions, and often at the end of the workday, I go into the files you worked on, just to shep nachas. I see all your great saves, and so does the Eibeshter. Keep up the great work.

15

Do you go for “Reb,” “Rabbi,” “Rav,” or R’?

The determination for who gets “Rav” and who gets “Rabbi” is a judgment call, often made by our rabbinical board. Anyone can be a “Reb,” from Reb Moshe or Reb Yaakov to Reb Shepsel at the shtiblach.

Absolutely no one gets R’ — that’s just laziness.

16

Do you find that readers notice mistakes?

Oh, yes. Mishpacha has a very literate readership. Sometimes they catch things that got by the writer, two editors, and two proofreaders. If there’s a mistake, our readers will spot it.

17

What’s your answer to people who write in saying, “I spotted this mistake in the magazine, can I become a volunteer proofreader?”

Ha-ha — first of all, I don’t think anyone has ever offered to do this job for free.

When we get this kind of comment, I tend to adopt a middah k’neged middah approach: Does this email contain any mistakes?

If not, maybe we’ll send this person a proofreading test. Incidentally, I developed a new test before our most recent recruitment, and the person who got the job scored 100 percent.

18

Do grammar and spelling stay consistent, or do you find you’re constantly having to keep on top of changes in the English language?

Yes and yes. Grammar and spelling tend to stay consistent, for the most part. Often when someone wants to use the singular “they,” I find that a plural “they” works just as well.

But we definitely need to keep on top of changes in English. New phrases and terms from high tech, therapy, and business are becoming mainstream all the time. You have to be able to recognize them and know when they’re being used properly.

19

What kind of mistakes make you cringe?

Don’t get me started. I’ll run out of space. Here are a few:

- “besides for” — This is simply not English; use either “besides” or “aside from.”

- “in middle of” — The proper form is “in the middle of.” Example: In the middle of has a “the” in the middle of it.

- “heart-wrenching” — It’s either “heartrending” or “gut-wrenching.” You can’t say “heart-wrenching.”

- “would have/would have” — Instead of “If I would have won the lottery, I would have been rich,” say “If I had won the lottery, I would have been rich.”

20

Are there any writers whose work barely needs proofreading?

Some need less, some need more. But even our very best writers need proofreading. We’re all human.

Questions for 20 Years

Coming up:

Nina Feiner, Sales Manager, North America

The Kichels Team

Send your questions to 20years@mishpacha.com

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1022)

Oops! We could not locate your form.