Faced with the prospect of his imminent betrothal to the daughter of the village chief, Yakob flees at night through the mountain

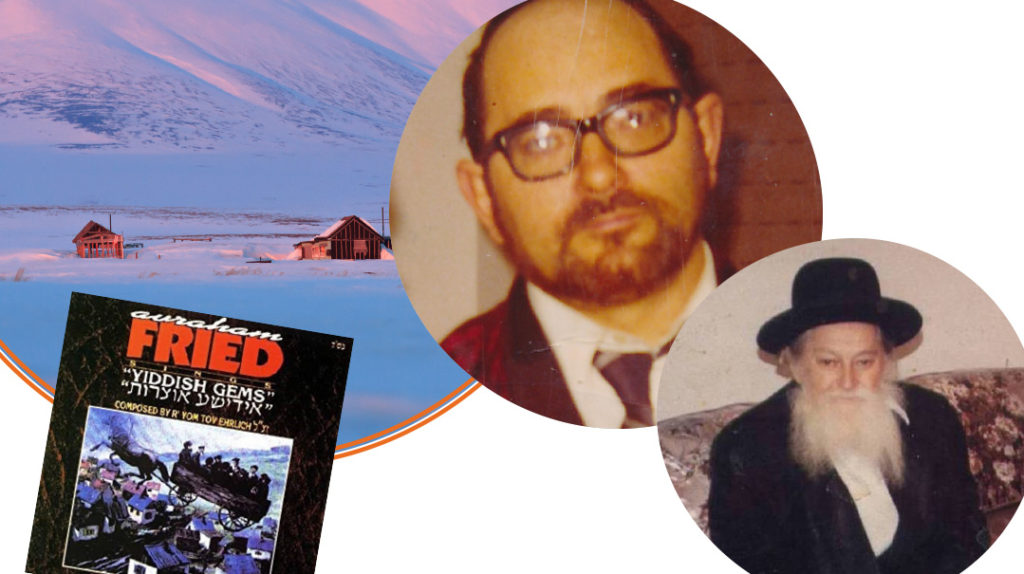

Yakob

Composed by: Reb Yom-Tov Ehrlich

Album: Yiddish Gems Vol. I

Singer: Avraham Fried

Year: 1992

The Song

“Yakob” is a ballad in rich, lyrical Yiddish, set to a distinctive melody in several parts, each section providing a musical backdrop to the tension of the story. The song tells the true story of a lonely bochur (Reb Yaakov Potash) singing at nights in the fields of Tajikistan, where he escaped during the Holocaust. Yakob’s niggunim are songs of longing for his parents’ home and the world of the yeshivah — “Ramban, Rambam, Rabbeinu Tam, nisht du of der velt ah bessereh taam...” — while his persona is a mystery to the peasants around him. When faced with the prospect of his imminent betrothal to the daughter of the village chief, Yakob flees at night through the mountains.

The Backstory

Rabbi Henoch Potash, son of Reb Yaakov Potash

Yom-Tov Ehrlich wrote this song in honor of my parents’ wedding in 1946. Reb Yom-Tov was probably the first person to converse with my father after his harrowing escape from Tajikstan and the imminent marriage to the chief’s daughter.

My father left this world at 53; he never bragged, and he never really sat down to tell us his stories. What we do know comes from what he told his friends immediately after the war, and from small snatches of information that he told my older brother or me.

To understand my father’s story, you have to understand where he came from. He was born in Radzymyn, a little town next to Warsaw. His mother was an exceptional woman, but not healthy, and his father was a much older man who had been married previously, so Yaakov was a young child with many half-siblings and an elderly father. At eleven and a half, he was sent to the yeshivah in Baranovich. His parents were too frail to take him there, so a cousin escorted him on the train.

Baranovich hosted the famed yeshivah led by Rav Elchonon Wasserman. To my father, the fact that there was no kitchen and that meals had to be eaten with families in the community was a difficulty, so he soon transferred to the nearby Slonimer yeshivah. Then, when Rebbe Moshe, the Stoliner Rebbe, opened a yeshivah, my father was among the small group of bochurim in the founding group. I don’t even know where he became bar mitzvah.

When the fighting of World War II came closer to the Stolin area, Rebbe Moshe of Stolin Hy”d told the bochurim to flee, saving their lives. My father went to Vilna, which was a safe haven and a gathering place for yeshivah students at that time. He approached the Mirrer mashgiach, Rav Yechezkel Levenstein, and asked if he could join them. Rav Yechezkel’s response was an offer to farher him. My father said, “I didn’t come to be farhered, I came to learn.”

His next effort, to enter Rav Aharon Kotler’s Kletzker yeshivah, was successful. Rav Aharon took him in, and although he was only 15, my father thrived in his shiur. Soon, though, the Nazis broke their pact with the Soviets and marched into Lithuania, and it was time to run again.

My father was sent east, deep into Tajikistan, which was then Soviet territory. He found himself on a kolkhoz (communal farming village) inhabited by gypsies, and he hid his Jewish identity. He didn’t want to sleep together with the non-Jews in their quarters, so he spent the nights sleeping on the forest floor. He told us that he once awoke to see eyes in the darkness — a wolf standing next to him. He rubbed two stones to make a fire, and the wolf ran.

My father was physically very strong, and everybody admired his prowess as a farm worker. At night, he’d “borrow” a tractor and continue working the fields in order to make a few pennies. At one point, he caught malaria and they had him taken to a hospital. After years of sleeping on the ground, he couldn’t sleep in the hospital bed. He told us that he was so ill then that he said Vidui, but baruch Hashem he recovered.

It seems that there was no one in the kolkhoz as handsome, strong, and capable as my father, and after some time, the head of the farming village decided that he wanted him for his own daughter — I have to add that my father never told me this piece of the puzzle. I heard it from a friend of his, Rabbi Yankel Goldstein, and from Reb Nachman Schneider, who heard from my father.

He couldn’t stay there any longer — refusing the chief’s offer would be unforgivable. There was no time to waste either. The chief’s honor would not allow him to back down and he’d come up with some ploy to trick my father into a staged betrothal. My father’s solution was to flee at night. He told me that in order to escape without a ticket and without visas, he traveled for 72 hours holding on to the ladder on the side of a moving train, with his feet wrapped around it, so he would not fall off if he fell asleep. The train crossed the border into Uzbekistan, and my father helped some smugglers take their packages across.

When they reached the city of Samarkand, my father got off, since there was a Jewish community in the city, as well as many refugees. His hair was overgrown after four years with the gypsies, and his hands and face black from soot. He wore a red kerchief tied around his head in place of a yarmulke, and his clothes were so torn that he had to stand sideways. He headed to the beis medrash, but of course, no one recognized this filthy stowaway as the yeshivah bochur Yaakov Potash. He told me that even people whom he knew from Kletsk would not take him in because of what he looked like.

The first person to offer to take the refugee home was Yom-Tov Ehrlich. I heard from his sister, Mrs. Kalushiner, that when Yom-Tov brought my father to their two-room quarters in Samarkand, her mother ordered all the children out of the house. The strange bochur went into one room, threw his pants over the door, and Mrs. Ehrlich sewed up his clothing. My father later ended up staying with Telshe Rosh Yeshivah Rav Chaim Stein’s parents-in-law. He helped get papers for Rav Chaim, for which Rav Chaim was always grateful.

After the war, my father moved on to Paris. There he met my mother, who was also a refugee from Eastern Europe, and they married. At the wedding, my father’s friend Yom-Tov Ehrlich played and sang the song “Yakob,” based on my father’s story. Part of the song, where the chief is offering him his daughter as a bride with a dowry, uses a niggun that my father himself had composed.

Asked in later years how he remained such a staunch Yid when he was alone in the world, completely cut off from Yiddishkeit from ages 15 to 19, my father used to reply, “It was my mother’s kishke.” What he meant was this: His mother was a choshuve lady, but infirm. From the beginning of the week, Sunday or Monday, she would start to plan for Shabbos. The family was poor, and her conversation with her husband would be about, “Tzu vet zahn genug mehl far kishke far Shabbos — Will there be enough flour for kishke for Shabbos?” The outsized importance that she accorded Shabbos imprinted itself on the child’s mind and replayed itself when he faced temptation. In the lyrics, Yom-Tov changed the kishke to Shabbos licht, which I guess sounds better, but that was what it was based on.

And at the shivah for my father, all Yom-Tov would say was, “Dein Tatteh is gevehn a tzaddik.”

From the Composer

Reb Elimelech Ehrlich, son of Reb Yom-Tov Ehrlich

My father produced an astounding 36 records of his compositions, but some were not professionally recorded. “Yakob” was on an album of his called Torah, released in 1961.

My father was with his family in Samarkand when Yaakov Potash arrived there after his flight from Tajikistan. When he came to the beis medrash there, no one believed he was really a yeshivah bochur, until he related something he had learned from Rav Aharon Kotler. My grandparents took Yaakov in, and when they made their way to Paris in order to get from there to America, he went along as part of the family. He married there, which is when my father first sang “Yakob.” Later Yaakov and his new wife immigrated to America too.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 854)