Words of Fire

Rav Shlomo Brevda ztz”l was known as a maggid who traveled around the world giving shiurim, and his listeners knew they were in for a journey that would carry them to vistas overlooking all of human history and the cosmos.

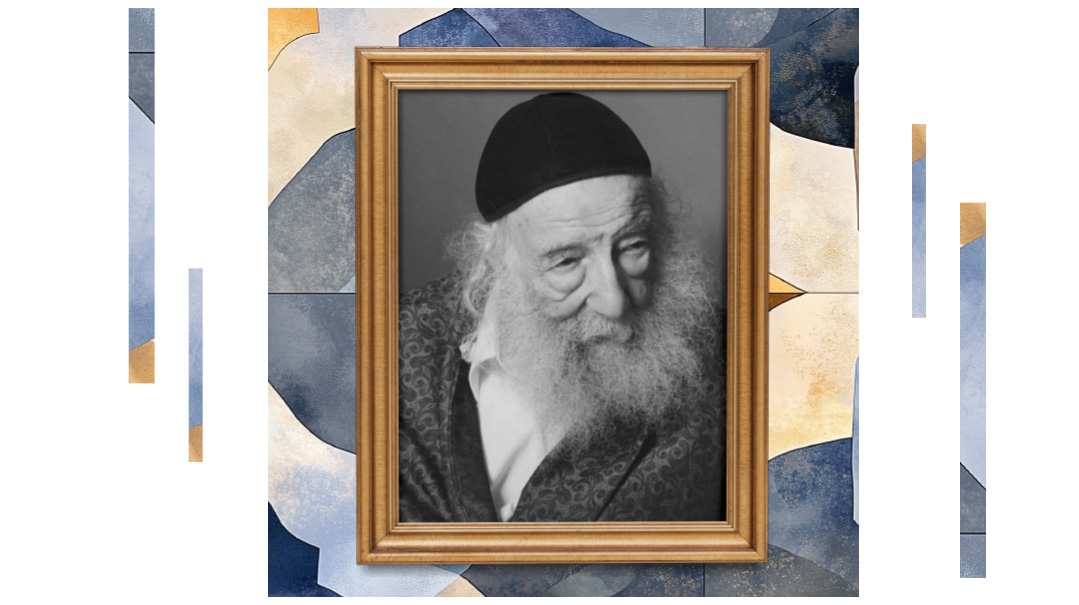

Rav Shlomo Brevda ztz”l, who was niftar in Brooklyn on 26 Teves 5773/January 8, 2013, at the age of 81, was known to most people as a maggid who traveled the world giving shiurim — perhaps most famously his drashah on Purim and the Megillah. A shiur from Rav Brevda took the listener on a journey from the often prosaic immediate surroundings to a commanding vista overlooking all of human history and the cosmos — interspersed with wry observations and tart commentary along the way.

A recent visit to his son-in-law and daughter Rav Asher and Rebbetzin Estie Druk in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Ramat Shlomo revealed a deeper side to Rav Brevda, a side he mostly kept hidden from the world at large. Even the concealed parts of his life, though, served to buttress and support the drashos that made him a familiar name.

“My father [famed Yerushalmi darshan Rav Mordechai Druk] used to say that what we once called a drashah is today called a hartza’ah a ‘lecture ’” says Rav Asher Druk a son-in-law of Rav Shlomo Brevda ztz”l who passed away a month and a half ago after a prolonged illness. “The darshan the one giving the drashah was doresh from the tzibur he demanded something of them he made a claim on them. These days he doesn’t demand from them he gives them a hartza’ah — he wants to be meratzeh his friends to ‘appease’ them. My father-in-law was a darshan!”

“Above all my father was doresh from himself” reflects Rebbetzin Estie Druk Rav Brevda’s daughter. “He never spoke a lot at home. He left all the speaking for the drashos. He lived for speaking. Our whole life revolved around my father’s speeches — to the extent that I didn’t even have time to get engaged to my husband. It was during bein hazmanim and my father had drashos scheduled in advance one after another. He used to have six to eight a day. My husband and I met very few times and baruch Hashem it went very quickly. But my father couldn’t cancel all the drashos he had scheduled — in the Negev in the north. All these people were waiting for him. Finally there were two drashos one night that he was able to shorten and the first picture we have as a chassan and kallah was taken at 1:20 in the morning.”

Hold the Pickle

Rav Brevda famously spoke on a wide variety of topics although his drashos on Yamim Tovim were particularly sought after. But he had a special interest in the subject of how a Jew should eat and this interest came to hold a central importance in his life and worldview.

“Once he was giving a drashah here in Yerushalayim in Yiddish on the subject of eating Yerushalmi kugel together with pickles” Rav Druk who lives in Jerusalem’s Ramat Shlomo neighborhood recalls. “He went into great detail about the kugel and the pickle joking about it for half an hour how a person should not be drawn after that and the effect it has on a person. Someone who was there told me later that he couldn’t eat pickles after hearing that drashah.

“Another time he was speaking in Lakewood at Beth Medrash Govoha” he continues. “He saw a bochur bring in a large bottle of Coca-Cola. This bochur’s chevra thought that he was bringing it for all of them but my shver watched in amazement as this bochur drank the entire bottle himself in one afternoon. My shver did not fail to mention this in the drashah he gave there. He said this bochur must have had a real svara — a svara! A svara!”

His reproof to his listeners could carry a sharp sting but it was always delivered with a therapeutic intent. And as his daughter Rebbetzin Druk observes sometimes medicine is best not administered with a spoonful of sugar.

“My father was a real ish emes” she says. “He wanted people to like what he was saying but he often held himself back from saying beautiful things because he wanted to give the right message to get the listeners to change. That doesn’t always go with hearing beautiful things. It can be very painful to hear what the emes is. So if he had a dei’ah about the Coke he said it even though they might not invite him back for a long time.”

And as demanding as he might have seemed to his listeners, he was always harder on himself. Rebbetzin Druk offers firsthand testimony.

“I never saw my father eat except when he was sitting down at a table, with a tablecloth, and a napkin spread out before him,” she says. “Food was eaten with a fork and knife. I never saw him eat a sandwich — never. When he ate a piece of bread, he would put it on the napkin and tear off a little piece. When my mother would serve him he would say, ‘Whatever you’re planning on giving me, give me less.’ He took only small portions. And he never took seconds. He trained his mind that when he finished his plate, he had finished the meal. And when you finish eating, you bentsch, you get up from the table, and you move away from there. You don’t sit and sit.”

In essence, Rav Brevda’s approach was to be in control of eating, and not to let the eating control him. Rebbetzin Druk illustrates this with a Purim-themed anecdote.

“My mother’s hamantaschen were always very popular,” she recounts. “One Purim, when I was a very young girl and we lived in Bnei Brak, my mother made the hamantaschen, but my father was not able to eat them — he was under restrictions from his doctors on what he could eat, and one of the ingredients was not okay for him. I remember my father getting up from his place in the dining room and making his way through the shalach manos piled high. He went into the kitchen and said, ‘I’m going to smell one hamantasch.’ He picked up a hamantasch, he smelled it, and he said, ‘Ah! Hamantaschen like Mamme makes, you can’t find in the whole world.’

“What did we gain from this? Number one, my mother’s beaming. Number two, it taught us that if you’re not allowed to eat, you don’t eat. It was a tremendous limud that I remember until this day.

“I’m certain that my father used to be mechavein kavanos with every single bite he chewed,” she says. “I have absolutely no doubt. His eating was absolute avodas Hashem. It’s not anything that our generation can even get. As a girl, there were certain things that I saw that I used to think were normal; that is what a father is all about. But when I grew up and I saw other hanhagos, I saw that not every father is like that.”

Money Matters

Rebbetzin Druk remembers that in addition to eating, there was another very human foible that her father faced down with fierce determination: anxiety over money. He sought to impress upon his family the importance of emunah and bitachon in financial affairs, and brooked no arguments in this area.

“He said his father would say to him, ‘There are two things in This World that are already enough of an embarrassment — you have to eat, and you need money. At least don’t talk about it.’ He never let us talk about food or money.

“When he used to come home from a drashah,” she recalls, “he would come in and put the money on the table and go away from there. My mother would then take the envelope — she handled the money for him. He never had a wallet. My mother used to give him whatever money he needed when he had to go out. He never knew if or how much money there was. He never asked.”

Above all, Rebbetzin Druk says, he wanted to convey the importance of vatranus.

“On Purim he kept a plate in front of him that said ‘Tzedakah l’aniyei Eretz Yisrael,’ to which people would donate. From this money he gave out envelopes every month to families in Eretz Yisrael who he thought really needed it. One year, some of the money was in sterling, some of the money was in euros, some in dollars, and he needed to change it all into shekalim. My mother called up my husband and asked if he knew anywhere in our neighborhood where he could change this money for a good rate. So my husband called up one of the money changers here, who gave him a rate. He told my mother the rate. Then my husband called another money changer, and this one gave a much cheaper rate.

“When my husband came to get the money from my mother, the first money changer called my husband on his cell phone to ask when he was coming to change the money. My husband said, ‘I just asked you for your rate.’ The money changer said, ‘Oh, I thought you would be coming to do it.’

“My father, who was learning in the next room, had his antennas up. He said, ‘What are you talking about over there?’ Before my mother could even finish explaining, my father said, ‘You give it to the first person he asked.’ My mother said that the first one was taking a much higher rate. ‘I don’t care,’ my father said. ‘The first person he asked is the person he gives it to.

Rebbetzin Druk herself once had an opportunity to put into practice the principles she learned from her father — and gave her father the opportunity to shep nachas.

“When I was a teenager there was a camp that hired me to handle the arts program,” she says. “We made up at the beginning of the summer how much they were going to pay me — about $1,200. It was not a small sum for a 16-year-old in those days.”

In return for the salary it promised, the camp received a sterling effort from its 16-year-old employee.

“I used to sometimes stay up the whole night, I had so much to do,” Rebbetzin Druk recalls. “When the end of the summer came, they told me that I was supposed to be getting up very early with the girls in the arts program to daven Shacharis. That was not anything that had been mentioned to me in advance. I just simply couldn’t get up so early after being up so many hours at night. So they told me they had to dock for each day I didn’t get up to daven Shacharis. At the end of the summer I had practically nothing left out of the $1,200 I was supposed to get.

“My father heard about it and asked me, ‘So what do you say?’ I told my father that I had such a good time in the summer, and I made new friends, and I really didn’t care so much about the money. My father had such a reaction! He practically jumped up and said, ‘You don’t care about the money? You don’t care about the money? Du bist meine tochter!’

All the Way

The chumros that Rav Brevda took upon himself were not ends in themselves but rather means to a very specific goal — cultivating sensitivity to the needs of others.

“It was a very big inyan by him not to be a farzichnik — a selfish, self-centered person,” Rav Druk says. “He said that one should always see the other person. He had a tremendous sensitivity to other people.”

“I never saw my father cry for himself,” Rebbetzin Druk adds. “I did see him on many occasions cry for others. He never had tainehs about anything Hashem did to him. Never. But once, a member of the family lost a baby. He called up their house and asked to speak to the mother. He was so choked up, he couldn’t speak. He cried for 15 minutes straight. She will never forget the nechamah it gave her.

“The pasuk in Parshas Vayeitzei says ‘Sulam mutzav artzah.’ That was his strength, the way he was hard on himself. But [the ladder] was mutzav artzah hashamaimah — he was also able to see above himself, into the depths of every person’s needs.”

“It says in Gemara Shabbos, ‘Kol ha’oneh amen b’chol kocho, poschim lo shaarei Gan Eden,” says Rav Druk. “Amen is the roshei teivos for achilah, mammon, and nashim. My shver said that one who subdues himself in these three areas — eating, money, and taivos — comes inside the gates of Gan Eden. He was machmir on himself with eating, and with money, in order to subdue his gashmiyus.

“Together with that,” continues Rav Druk, “he elevated his ruchniyus through his chivuv hamitzvos. He spent money freely on mitzvos — buying ten esrogim, even a mehudar Teimani esrog, for Succos, and the most mehudar matzos for Pesach. The chivuv hamitzvos brings sipuk and simchah to the neshamah. And he taught that if one subdues his gashmiyus and elevates his neshamah in this way, this enables him to clearly perceive the needs of others.

“Hu hichnia al atzmo l’gamrei, k’dei l’hargish et hasheini, ad hasof — he completely subdued his needs and wants, in order to feel the needs and wants of the other person, all the way.”

Yehi zichro baruch.

True Simchas Purim

Rav Brevda’s loss will be keenly felt by many at this time of year. His memorable drashah on Purim and the Megillah was always eagerly sought out by audiences wherever he traveled.

“One time Rav Shach came to visit my shver when he wasn’t feeling well,” Rav Druk recalls. “Rav Shach said, ‘Whoever didn’t hear Rav Brevda’s peirush on the Gaon never experienced true simchas Purim!’

“In his drashah on Purim, he would combine the peirush of the Gra with his own, and he would show how the nissim of Purim began from the first pasuk of the Megillah,” Rav Druk explains. “For example, Chazal darshen from the pasuk ‘Hamolech’ that Achashveirosh rose to the kingship on his own — he was not the son of the previous king, he only minded the royal stables. His ascent to the kingship was the first step in Hashem’s plan to bring the Jews to teshuvah for an aveirah they had committed years earlier.”

Nebuchadnezzar, the Babylonian king who conquered Eretz Yisrael and forced the Jews into galus Bavel, had constructed a statue of himself that was 60 amos tall. Nebuchadnezzar ordered all the nations under his rule to come before the statue and bow down to it. Only Chananel, Mishael, and Azaryah didn’t bow down. But Rabi Shimon bar Yochai says in Gemara Megillah there were Yidden who did bow down to it, out of fear of Nebuchadnezzar. The Jews did not do teshuvah for this; they claimed that they were coerced.

When there is no teshuvah for an aveirah, Rav Brevda said, there is a thundering mekatreig created in Shamayim that roars, “Eibeshter, how long will You allow this rebel to exist in Your world?” The sound from it is unbearable. On the other hand, Rav Brevda cited a passage in the Zohar that says the moment a Jew opens his mouth and says “Ana Hashem, chatasi,” the mekatreig is silenced. “The minute you’re modeh, the kitrug stops,” Rav Brevda said.

But in this case, the kitrug didn’t stop; it went on for years and years. After the Persians defeated the Bavlim, Achashveirosh, acting on the advice of Haman, enticed the Jews to an illicit seudah, while the mekatreig was still roaring in Shamayim over the first aveirah from years before. And, Rav Brevda points out, Rabi Shimon bar Yochai writes that the Yidden were “nehenu miseudaso shel Achashveirosh” — the Jews enjoyed the seudah. Hashem therefore wrote a gezeirah that the Yidden should be destroyed. The only way they could be saved was through teshuvah. Rav Brevda contends that the whole theme of the Megillah, then, is to show how Hashem gets Mordechai and Esther into place to be able to bring Klal Yisrael to teshuvah.

And the rest, as they say, is history.

Rav Shlomo Brevda (1931–2013)

Hearing his pointed observations about American Jews, a listener might have assumed that Rav Shlomo Brevda had been born in Europe. In fact, though, he entered the world in 1931 in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, not long after his father, Rav Moshe Yitzchak Brevda, moved the family to US shores from Baranovich, Poland. After cheder he went to learn in YU’s Yeshiva Rabbeinu Yitzchak Elchanan, and was on a typically American track to college.

Then he encountered the Mirrer Yeshivah, which had just landed in New York, having been plucked from the fires of war in Shanghai in 1947. He formed a lifelong kesher with Rav Chatzkel Levenstein, and would go on to learn in Lakewood with Rav Aharon Kotler. He later went to learn in Eretz Yisrael, where he also formed connections with the Brisker Rav, Rav Chaim Shmuelevitz, and the Chazon Ish. The Brisker Rav famously opened his yeshivah expressly at the request of Rav Brevda, then still a bochur.

After marrying his rebbetzin, Leah Greenblatt, a daughter of Rav Avraham Baruch Greenblatt and sister of Memphis’s well-known Rav Ephraim Greenblatt, Rav Brevda returned to the US and worked in chinuch for a few years. He then moved with his family back to Eretz Yisrael, calling Bnei Brak home as he embarked on his long, illustrious speaking career. He was niftar in New York during an extended visit there. He is survived by his rebbetzin and three sons and three daughters.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 448)

Oops! We could not locate your form.