With Chains Unbroken

The Novominsker Rebbe was taken at the moment he was needed most. Three years later, his two sons share their perspective of the rebbe who was a father to so many

Photos: Naftoli Goldgrab, Mattis Goldberg, Mishpacha and family archives

The car drove slowly down the unpaved road, tire marks forcing a patterned design, pebbles scurrying for dear life. The throngs escorting the vehicle kept growing and the song swelling from their throats continued to grow as well. “Yamim al yemei melech tosif,” they sang: Let the days of the king increase, may he live, may he lead, may he continue to inspire.

Necks craned, hoping to catch one final glimpse of the radiant face, the gray-white beard, the twin eyes of smoldering black. His visit had been the highlight of camp, and they were reluctant to let it go.

But suddenly, inexplicably, the passenger’s window rolled down — what was the Rebbe looking at? His gaze focused on one boy standing off in the distance.

“Moishy! Moishy!” the Rebbe called.

Moishy looked up, smiled, and waved. The Rebbe smiled as well, waved in return, and closed the window.

The crowd continued singing and the Rebbe sat contentedly back in his seat. Within the scores of people, he had spotted Moishy, a talmid of his beloved yeshivah. The car rolled on, grinding through a final jagged path, adjusting itself to a more cultured highway, and driving off into the sun. And Moishy trotted to the dining room, a jump in his step.

The Rebbe had waved to him.

I

t’s a story of humility, love, and a complete negation of honor, some of the signature qualities of Rav Yaakov Perlow ztz”l, better known as the Novominsker Rebbe. His story is a trail of snippets of greatness tucked within the simplicity of everyday experiences. Authentic joy at the sight of a talmid working as a camp counselor is just one of them.

He was a once-in-a-century personality, a gadol in Torah, ahavas Yisrael, and avodas Hashem. But there was one singular feature that permeated the Rebbe’s legacy.

He was a gadol in leadership. Not through power or dominance, but through abject selflessness and so much pride in his people.

American born and American raised, he was an impressionable young teenager when the news of unfathomable tragedy began trickling in. He was there when the survivors limped ashore, broken bodies, bleeding hearts. A young Yaakov Perlow watched, and something inside him stirred.

There was nothing he could do about the past. It was finished, gone, over. Six million souls ago. But there was still a future.

There was, wasn’t there?

It wasn’t so simple. The Rebbe would often share the memory of a time when he went together with his father, the previous Novominsker Rebbe, to the Agudah Convention of 1946, held in Belmar, New Jersey. The leading gedolim were there — Rav Moshe Feinstein, Rav Aharon Kotler, Rav Elya Meir Bloch.

But it was a speech given by Rav Yisroel Zev Gustman that echoed in 15-year-old Yaakov Perlow’s mind forever. Standing before thousands of people, Rav Gustman began by saying, “Ich vil yetzt gebben a hesped oif Klal Yisroel! — I will now deliver a hesped on Klal Yisrael!” As if cued in advance, the entire audience burst into tears.

Time passed, revealing a stunning revival, and the Rebbe rose to rejoice in that miracle, to celebrate the future of a past he never met. Fluent in both English and Yiddish, with a natural understanding of American culture and a keen familiarity with European tradition, he was perfectly suited to build the critical bridge between then and now.

The Rebbe would be there to unite a people who statistically shouldn’t exist. He would be there to love. He would be there to teach.

He would be there to lead.

Klal Yisrael grew, and the Rebbe’s heart grew along with them. For 22 years he served as Rosh Agudas Yisrael, and, from that vantage point, his loving gaze took in a panoramic view of Klal Yisrael. From hundreds of podiums throughout the world, he presented the themes of kevod Shamayim, ahavas Yisrael, and devotion to Torah with singular eloquence and unbending conviction; a rejuvenated people absorbed the message, perceiving its truth and sincerity.

And then, three years ago, just two days before Pesach, as a windstorm of confusion ripped through the world and a terrified society stayed locked within the confines of perceived safety, the Rebbe slipped away. A leader was gone, at the moment he was most needed.

But captains never abandon the ship. The Rebbe always took so much pride in his own children, spending hours each day in their company, speaking to them in learning and then sharing their chiddushim with others. The Rebbe is gone, but his children are here. He instructed that his twin sons, Reb Yehoshua and Reb Yisroel, each assume the title Rebbe; their appearance is near identical, but that’s not the only commonality they share. Tremendous talmidei chachamim in their own right, the two current rebbes carry an air of humility so reminiscent of their father.

Reb Yehoshua, in addition to his position as 11th-grade maggid shiur in Yeshivas Novominsk, has taken over the Rebbe’s role in leading the Novominsker kehillah in Boro Park. Reb Yisroel, in addition to his position as the first-year maggid shiur in Yeshivas Novominsk, also leads a Novominsker kehillah in Lakewood, where he spends each Shabbos.

As I sit across from them, listening to the sharp intellect couched in that familiar modesty, my mind travels back to the car rolling slowly out of camp and a timid Moishy, now bereft of a rebbe who loved him so much.

Rebbe! Rebbe!

Somewhere, the Rebbe smiles and waves back.

Exert Yourself

Each year on Erev Rosh Hashanah, Rav Yehoshua Perlow would drive his father to the beis hachayim so that he could daven at the gravesite of his father, the previous Novominsker Rebbe, Rav Nochum Mordechai Perlow ztz”l. On those trips, the usually amiable Rebbe would grow uncharacteristically quiet. Reb Yehoshua asked him why.

“When it comes Rosh Hashanah time, I remember the intense avodah of my father and my ancestors,” he responded.

Reb Yehoshua understood what the Rebbe meant. “My father saw his illustrious ancestry as a tviah, a demand, that he too, strive to greater heights. He was daunted by the challenge.”

It was, indeed, a tall order.

The Rebbe, born in Cheshvan of 1930 to Reb Nochum Mordechai and Rebbetzin Baila Ruchama Perlow, was the youngest rung in a ladder that stretched all the way back to the Baal Shem Tov. Along the way were his grandfather, Reb Alter Yisroel Shimon Perlow, known as the Tiferes Ish, and great-grandfather Rav Yaakov Perlow, known as the Shufra D’Yaakov. The Rebbe was also a descendant of Rav Mordechai of Neshchiz, Rav Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev, and the Chernobyler Maggid, among many other great tzaddikim.

His marriage in 1956 to Rebbetzin Yehudis Eichenstein a”h added a list of ancestors-in-law that included the Zhiditchoiver dynasty and, even after the Rebbetzin’s passing in 1998, the connection to Zhiditchoiv remained as the Rebbe remarried his late wife’s sister, Rebbetzin Miriam yblch”t.

For the Rebbe, living up to heightened standards wasn’t just an option for someone with impressive yichus — he saw it as a defining characteristic of avodas Hashem.

“He would often quote the Gemara in Chagigah [9b], about the incomparable difference between one who learns a perek 100 times and one who learns it 101 times,” says Reb Yisroel. “He would then say in the name of the Baal HaTanya that the reason for this is that, in those days, it was the expected norm to review a chapter 100 times. Therefore, one who studies 101 times has gone beyond expectations. Someone who extends himself to go one step beyond what is customary is incomparably greater than one who hasn’t taken that step.”

The Rebbe would repeat this idea from the Tanya and then cry out, “Mir darfen zich ibbershtrengen! We must exert ourselves!”

The Rebbe was quiet on his way to his father’s kever, and through the silence of the graveyard came a call that only he heard. Novominsker Rebbe, mir darfen zich ibbershtrengen! We must exert ourselves!

Perhaps the message found a special place in the Rebbe’s heart because he learned it from his own rebbe, the rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin, Rav Yitzchok Hutner ztz”l.

“The Rebbe was always makir tov to Rav Hutner,” says Reb Yisroel. “It was Rav Hutner who saw his potential to become a great talmid chacham and marbitz Torah. Rav Hutner was very much mechazeik him to take this direction. The Rebbe joined the kollel of Chaim Berlin, and remained there until he became the tenth-grade rebbi in Rabbi Breuer’s yeshivah in Washington Heights.”

The Rebbe would share a story that occurred while he was learning under Rav Hutner:

“There was a bochur in the yeshivah who came from Canada. He felt very much alone in the yeshivah and Rav Hutner took him under his wing. One day, the bochur’s uncle visited the yeshivah, and, to express his gratitude to Rav Hutner, he dropped off an envelope and proceeded to leave.

“Rav Hutner opened the envelope to find a check made out for a shockingly high sum of money.

“ ‘Reb Yid!’ Rav Hutner called out, and the receding back halted. ‘Reb Yid, why so much?’

“The fellow opened his mouth and out came the timeless answer. ‘Vus heist? A Yid darf zich ibbershtrengen! What do you mean? A Yid must exert himself!’

“Rav Hutner treasured this line. From then on, he would make concentrated efforts to go out of his way for the sake of his talmidim and, when asked, he would respond, ‘Vus heist? A Yid darf zich ibbershtrengen!’ ”

On Shabbos Hagadol the year before his passing, when he was already 88 years old, the Rebbe delivered a derashah and, once again, cried out “Mir darfen zich ibbershtrengen!” Shortly after Shabbos, the Rebbe was informed that a former talmid, who suffered from a debilitating illness, had passed away. The levayah was being held in Lakewood. The Rebbe insisted on going, even as worried children and talmidim tried to dissuade him.

“Rebbe, it will be too hard for you,” they reasoned.

Choking on tears, the Rebbe looked at them. “Hust nisht gehert vuhs mir huben geredt di Shabbos? Did you not hear what I spoke about on Shabbos? Mir darfen zich ibbershtrengen!”

There would be no hesped on Klal Yisrael. It would be hard, the adjustments would be rocky, and new challenges would constantly arise. But ultimately, they would succeed.

Rav Yehoshua (L) and Rav Yisroel Perlow share not only memories with Mishpacha’s Shmuel Botnick, but also a vision toward the future

Be Hashem’s Ambassador

A highly talented orator, the Rebbe was one of the most sought-after public speakers in the frum world. His endless repertoire of divrei Torah served him well for any occasion, but even as the content varied, the message was constant.

“The Rebbe’s primary message in all his speeches was the importance of being mekadeish Sheim Shamayim,” says Reb Yisroel. “He would emphasize how important it is for the tzibbur, as well as the individual, to serve as Hashem’s ambassador.”

The Rebbe lived with a very sharp discernment of the constant tightrope that must be walked by an insular people interacting with an overly tolerant society. He would often quote a gemara in Yoma (86a) that the command of v’ahavta es Hashem Elokecha doesn’t just mean that you shall love Hashem. In addition to its simple translation, it also means “sheyehei Sheim Shamayim mis’ahev al yadcha — that the Name of Heaven should be beloved through you.” The Rebbe would quote this gemara, emphasizing how it is every Jew’s responsibility to act in a way such that those who may be watching will see the grandeur and the nobility reflected by those who serve Him.

And it wasn’t just lip service — the Rebbe lived with this ideal. On one of his annual trips to Eretz Yisrael, he told his daughter Rebbetzin Sara Chana Treger to make sure that the tuna sandwiches she packed for his trip home would not have any vegetables in them.

“So just plain tuna?” she asked, perplexed. “But why?”

“Because,” the Rebbe replied, “I usually don’t finish the sandwiches by the time I arrive in New York. When you arrive in America, one of the questions they ask you at customs is whether you’re carrying any fruits or vegetables. If there’s lettuce in my leftover sandwich, how can I say no?”

It’s a story of the Rebbe’s trademark middah of emes, but there’s another element to it as well. Throughout his life, he would maintain a standard of scrupulous honesty — because it’s the right thing to do, but also so that the world should note that there’s a nation called Klal Yisrael that is a paragon of integrity, honesty, and uncompromising righteousness.

“The Rebbe would frequently emphasize how we must live with a clear recognition of our responsibility in this world,” says Reb Yehoshua. “In his words, we must be ernste menschen, ernste Yidden — serious people, serious Jews. The Rebbe himself would always quote the phrase from Mesilas Yesharim, the always relevant question that we must ask ourselves: ‘Mah chovaso b’olamo — What is our obligation in this world?’ The Rebbe lived with this line and, when he spoke, he would demand it of others as well.”

The Rebbe would also share, in the name of Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, why the pasuk “V’nikdashti b’soch Bnei Yisrael — And I shall become sanctified among Bnei Yisrael” is written in the passive voice, as opposed to in the active voice as a positive commandment. We are taught that one who accidentally creates a chillul Hashem is held liable; this being the case, then certainly one who accidentally sanctifies Hashem’s name should be rewarded. It is therefore written in the passive, because kiddush Hashem can result even from our unintentional acts.

The Rebbe loved this idea. Elevate yourself, demand from yourself, become ernste menschen, ernste Yidden to the point where you’re making a kiddush Hashem even by mistake.

With Rav Chaim Kreiswirth

Over Your Head

The Rebbe demanded this because he knew it was possible. He saw that spark of divinity in every Jew — all he was asking was for us to see it as well. He saw it in adults, and he saw it in children. This may have been the impetus for the Rebbe’s creative perspective on how to educate children on the importance of mitzvos.

“The Rebbe felt that, in teaching the basic mitzvos to children, we should also teach them some of the deeper ideas found in the seforim hakedoshim,” says Reb Yisroel. “He held it was important, even if the children couldn’t fully relate to these concepts. At one of the Torah Umesorah conventions, the Rebbe spoke about inculcating in our talmidim a sense of hecherkeit, of elevating ourselves to higher levels.

“‘We should share these ideas with our talmidim, even if it means speaking above their heads,’ the Rebbe said.

“After Maariv, Rav Mattisyahu Salomon approached and said ‘Yasher koach!’

“The Rebbe brushed aside the compliment and said, ‘Lo hamidrash ha’ikur ela hamaaseh — there’s little value to the words unless they’re put into practice.’

“Rav Mattisyahu quickly responded, ‘Ober oib s’nit doh kein midrash, s’nit doh kein maaseh — If there are no words, then what would be put into practice?’ ”

Reb Yehoshua gives an example as to how lofty the Rebbe felt one could go in educating our children on the depth of the mitzvos. “There is an idea brought down from the mekubalim, originating from the Arizal, that the action of giving tzedakah outlines the four letters in Hashem’s Ineffable Name. The coin symbolizes the letter yud, the five fingers that hold the coin symbolize the letter hei (whose numerical value is five), the outstretched arm appears in the shape of a vav, and then the five fingers of the recipients reflect the final hei.

“The Rebbe held that this idea should be taught, even though it is advanced and esoteric. The children will hear it, even if they don’t grasp it. They will listen to the words and comprehend, at its very least, that something deep and majestic lies within the mitzvah of tzedakah.”

It was a consistent theory. That spark of covert divinity, invisible to so many, danced visibly before the Rebbe’s eyes. Teach it to the children, he instructed, let them know how special the mitzvos are, let them know special they are.

The beauty of mitzvos was something the Rebbe spoke about regularly, but the mitzvos of the Pesach Seder in particular held a special place in his heart.

“The Rebbe’s primary takeaway lesson from Pesach,” says Reb Yehoshua, “was the mitzvos that we observe at the Seder. He would quote the Rashi in parshas Bo about how Hashem commanded two mitzvos, dam Pesach and dam milah, as a precondition for the Jews leaving Mitzrayim. The reason for this, says Rashi, is that ‘lo hayu b’yadam mitzvos l’hisasek bahem, they lacked the requisite toil in mitzvos.’

“The Rebbe would see this as a lesson for all of time — that when Pesach comes around, in order to properly reenact the geulah of Mitzrayim, we too must focus on the performance of mitzvos.

“After eating the matzah, maror, and Koreich,” continues Reb Yehoshua, “the Rebbe was in a different world. He would say ‘Baruch Hashem, we were mekayeim the mitzvos!’ ”

Rabbi Nosson Muller, a close talmid of the Rebbe who, upon the Rebbe’s remarriage, became his son-in-law, once shared a story with the Rebbe. When the Ahavas Yisrael of Vizhnitz completed the Seder, he raised his hands to the heavens.

“Ribbono shel Olam!” he cried, “mir huben gegessen a k’zayis matzah [we ate a k’zayis of matzah]. Mir huben gegessen a k’zayis maror [We ate a k’zayis of maror]. Yetzt, Ribbono shel Olam, geb unz a k’zayis nirtzah! [Now, Ribbono shel Olam, give us a k’zayis of nirtzah, loving acceptance!”

The Rebbe heard this story, placed his head in his hands and burst into tears. The Vizhnitzer Rebbe’s tefillah, that in the merit of our mitzvos we should earn a true nirtzah, a total loving acceptance by Hashem, was too overwhelming. The Rebbe cried for some time and then lifted his head.

“Nussi!” he exclaimed, “If I were there, I would have said, ‘Vizhnitzer Rebbe! The k’zayis matzah, the k’zayis maror — that is the greatest nirtzah!’ ”

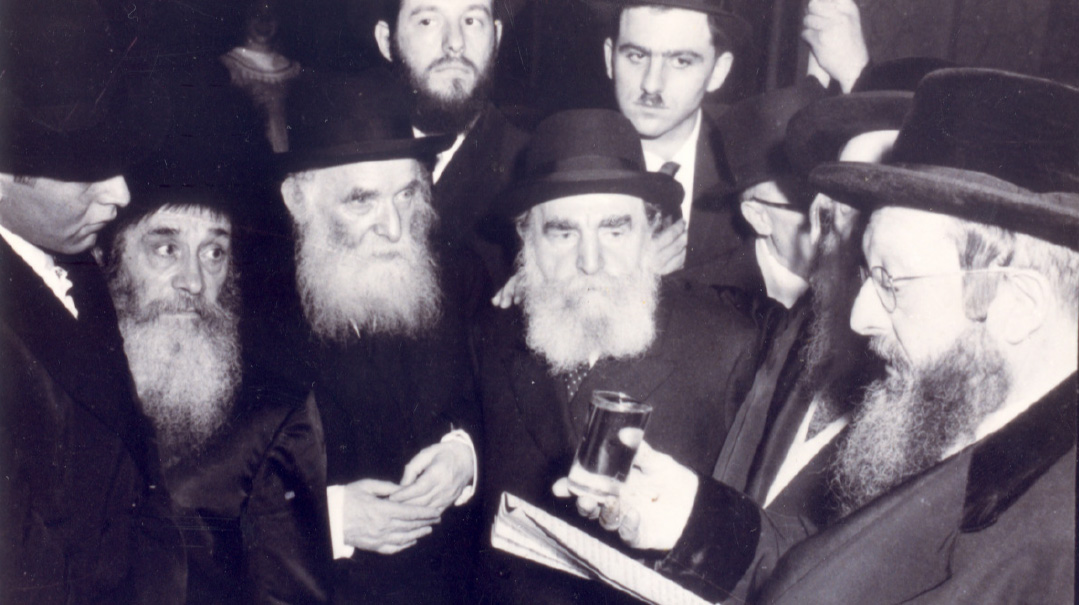

Flanked between Rav Aharon Kotler and Rav Moshe Feinstein. Whether with contemporary rabbanim or leaders of an earlier generation, the Rebbe’s natural place was amid gedolei Yisrael

Down to Earth

During the Seder, Reb Yisroel remembers, the Rebbe would have to catch himself — he was going too high. “He would pause, and then shift into a different mode, redirecting the discussion to address the children,” Reb Yisroel says.

Not just a lower-level discussion of the Haggadah, but whatever it was that a child would consider valuable.

Rabbi Muller remembers how one year, his young daughter found the Rebbe’s afikomen and proceeded to bargain for compensation.

“I want a camera!” she declared.

The Rebbe accepted the terms. “For sure,” he said, “I’ll give your father the money to buy a camera.”

He then turned to Rabbi Muller and said in a low voice, “Make sure it’s a good one.”

In a similar instance, a Muller boy found the afikomen, and a set of machzorim were subject to the negotiations. The Rebbe was quick to concede to the request. He agreed to sponsor the set of machzorim and, turning to Rabbi Muller, whispered, “Make sure they have his name engraved in gold lettering.”

Reb Yisroel recalls how, despite the personal heights he reached, the Rebbe reveled over the most elementary response to a question. “During the Seder, the Rebbe turned to a nephew who was just about kindergarten age and said, ‘Tell me, who was Avraham Avinu?’

“The boy immediately responded: ‘He was the first Yid and the first one to get a bris milah.’

“The Rebbe’s face lit up. He was thrilled with the young boy’s innocent perspective.”

It’s a striking dichotomy. On the one hand, the Rebbe would speak from the podium at the Torah Umesorah convention, insisting that young children should be educated on the abstract, trained to comprehend the more esoteric elements of ruchniyus. Yet, at the same time, he would exult over the most basic devar Torah.

But therein lay the secret. Within the purity of a four-year-old’s comprehension, the Rebbe discerned all the latent secrets and mysticism, waiting for the day they would be unlocked.

The Rebbe’s insistence that depth lay beneath plebeian surfaces was likely the secret to his optimism for Klal Yisrael’s future.

He loved to tell a story about the Ponevezher Rav returning to Eretz Yisrael from a fundraising trip abroad. “When he went to the bank to deposit the money, the secular bank teller launched into a diatribe about how Orthodox Jews are parasites, always financially dependent on others,” the Rebbe recounted. “The Ponevezher Rav looked at him and responded, ‘You know, the non-Jewish bank teller in Lithuania told me the same thing. But you know what the difference is? Your grandchild will learn in my yeshivah.”

After the Seder, the Rebbe had the custom of reciting Shir Hashirim. Written entirely in metaphor, its various interpretations abound, and according to Rashi’s approach, much of Shir Hashirim discusses the destruction of the Beis Hamikdash and the promise of renewal.

The Rebbe would mention this and then declare, “Shir Hashirim iz nisht Eichah! In Eichah, we talk about what was. In Shir Hashirim, we talk about what was and what will be!”

That spark of “what will be” was all the Rebbe ever saw.

A close talmid of the Rebbe once met an older man who revealed that he had been a classmate of the Rebbe since his earliest days in elementary school. One memory stood out.

“I remember how, one Chanukah, the Rebbe acted in the class play,” the fellow reminisced. “His role was to be the candle on the menorah. And he sang a song in Yiddish about how he, as a lichteleh, was tasked with spreading light to others.

“He sang with such sincerity… and look what he became,” the man exclaimed. “Look how much light he spread.”

The Rebbe’s life was an upward spiral of personal growth. As he strove to demand more and more from himself, those around him caught on

A Place in His Heart

The Rebbe’s genuine sense of inclusion for all Yidden wasn’t something he just practiced; it was part and parcel of his personality. He descended from a royal line of chassidishe rebbes, but he would constantly talk about litvishe gedolim, Yekkishe minhagim, Sephardishe history, all with indistinguishable enthusiasm and admiration.

“Tefillin darfen gemacht gevuren fin or echad,” the Rebbe would say. “Tefillin are required to be made from a single stretch of hide. But I am not made of a single stretch of hide.”

He most certainly was not. There was nothing exclusive about the Rebbe; he was made of a kaleidoscope of anything Yiddishkeit, appreciating the value of any heir to the legacy of Avraham Avinu.

This was evident even in the Rebbe’s employment history. After learning in Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin’s kollel, the Rebbe took a position as the tenth-grade rebbi in Washington Heights, where the predominant culture was that of German Jewry. He later moved to Chicago, where he taught in the Skokie yeshivah for seven years, whereupon he returned to Washington Heights to assume the position of rosh yeshivah.

None of these institutions were remotely chassidic, but the Rebbe’s devotion to his talmidim made clear that segments and denominations factored little, if at all, in his relationship with fellow Yidden.

In fact, it wasn’t until 1984 that the Rebbe established Yeshivas Novominsk in Boro Park, originally in the same building as his shtibel, known as the “Rebbe’s Beis Medrash.” It was in that setting — a shul, a yeshivah, a welcome affiliation more than a chassidus — that the Rebbe spent the rest of his life. But that didn’t stop him from maintaining the closest relationships with his talmidim from Skokie or Washington Heights.

And every one of his talmidim, no matter from when, forged a place in his heart.

Rav Dovid Zucker, rosh kollel of the Chicago Community Kollel, told of a time when his brother, a young man in his twenties, was diagnosed with a dreaded disease shortly after his marriage. The senior Mrs. Zucker decided to call each of her son’s rebbeim, one of whom was the Rebbe, to ask them to daven for him. It had been over seven years since the boy sat in the Rebbe’s classroom, but when the Rebbe heard the dire news, he cried out, “Oy! Daniel?!” and he burst into tears.

One of the Rebbe’s most oft-quoted expressions was culled from a gemara in Bava Basra (75a), which outlines an unusual scenario of angels debating the meaning of a verse. Malach Gavriel takes one position and Malach Michoel takes another. Eventually, Hashem’s voice rings out — “Lehevei k’dein v’k’dein! — May it be like this one and that one!” The Rebbe must have repeated this line hundreds of times in his life.

“Lehevei k’dein v’k’dein,” said the Ribbono Shel Olam. “Lehevei k’dein v’k’dein,” echoed the Rebbe.

It was in the macro — he loved Klal Yisrael as a nation — but it was manifest in the micro just the same.

“Even now,” says Reb Yisroel, “three years after the petirah, people approach me and say, ‘Dein tatteh felt ois — Your father is missed.’ ”

This sense of endearment and enduring connection, Reb Yisroel surmises, is a reflection of how much the Rebbe respected each person as an individual.

“The Rebbe was a very non-judgmental person,” Reb Yisroel explains. “He had a great ayin tovah and saw only the good in others.”

The Rebbe was known to be a very astute baal eitzah, and many came to him to seek his counsel. But he didn’t always give it.

“There was a Yid who was going through a great tzarah,” Reb Yehoshua recalls. “He came to the Rebbe and told him all he was going through. The Rebbe didn’t say anything, he just wept. The Yid later told me how meaningful that was, and how it really helped to alleviate his burden.”

It wasn’t just that he felt the pain of others. His ahavas Yisrael was a faculty of his mind much as it was of the heart. He was able to discern the pain of another because he understood it so distinctly. About 15 years ago, the Rebbe was sitting shivah for his brother, with whom he shared a very close relationship. Reb Berel Ostreicher, an elderly Yid who was close with the Rebbe, entered to be menachem avel. The Rebbe was aware that Reb Berel had just recently lost his wife and was able to read the searing pain on his face.

“Reb Berel,” he said, “Ich farshtei. Vus zuhl ich zuggen? Lumir chutsh veinen tzezamen — I understand. What can I say? Let us at least cry together.”

And together, they cried.

Rabbi Muller was once learning b’chavrusa with the Rebbe, who at the time was nearing his seventies. It was in the heart of the winter and an intense blizzard was rapidly smothering the city in a severe blanket of white. The Rebbe’s phone rang. Although the Rebbe never took phone calls during the seder, he noted the name on the caller ID and immediately reached for the receiver.

It was a woman who had been struggling with her marriage for some time and the Rebbe was actively involved with the case. But as the Rebbe spoke on the phone, it seemed that things had come to a head. Her husband had left home and no one knew where he was. The Rebbe hung up and sighed. He then put on his coat and boots and began walking toward the door.

“I’m sorry, Nussi,” he said to his much younger chavrusa, “I have to go find this man.”

“The Rebbe walked through the piles of snow,” Rabbi Muller relates. “He walked around all of Boro Park, going from beis medrash to beis medrash until he found him.”

No person was too young, no problem was too small. Rabbi Muller remembers another instance when he entered the Rebbe’s office, and the Rebbe’s expression showed that something was bothering him.

“I was just speaking with a bochur,” the Rebbe said. “He had a device that was presenting him with struggles in inyanei kedushah. I finally got him to give it to me.

“But don’t worry, Nussi. I made sure to pay him its value.”

“On several occasions,” says Rabbi Muller, “I was with the Rebbe when parents came with a complex challenge involving one of their children. The Rebbe would give explicit directions, outlining, in no uncertain terms, the course of action that must be taken. He demonstrated only strength and conviction. Then, the moment the parents left, he would break down in tears.”

It wasn’t just love. The Rebbe was proud of Klal Yisrael; he saw them as his family and cherished its accomplishments.

Reb Yehoshua shares a fascinating memory. “On Erev Yom Kippur, he would call our brother-in-law, Rav Yitzchok Treger, who lives in Eretz Yisrael. He would say ‘Reb Yitzchok, is it true that the majority of Jews in Eretz Yisrael fast on Yom Kippur?’

“When Reb Yitzchok would confirm that, yes, the most recent surveys indicate as much, the Rebbe was ecstatic, and would repeat this statistic multiple times throughout the day. ‘Rov Yidden in Eretz Yisrael fasten oif Yom Kippur!’ he would say with tears in his eyes. ‘What would the Berditchever say? Hashem, look at your children! Your children observe Yom Kippur!’ ”

It was an attitude he sought to foster in his talmidim as well. The talmidim of Yeshivas Novominsk go collecting on Purim, as do most yeshivah bochurim. The Rebbe allowed this practice, but with one caveat. No one was allowed to collect for the yeshivah.

“Only for others,” the Rebbe would say. “You can only collect for other Yidden.”

It wasn’t only on Purim. The Rebbe, through both quiet influence and overt messages, instilled his unique character into Yeshivas Novominsk, embedding it into its culture. Considered a top-level institution by all standards, the yeshivah’s learning is intense while its personality remains buoyant. The Rebbe’s infectious joy continues to permeate its atmosphere, even as the years after his passing draw on. Within the earnestness of a rigorous schedule, there is a tangible pulse of celebration that we, over any other nation, were endowed with the privilege of learning Torah.

Until the Final Day

When it came to the Rebbe’s ahavas Yisrael, it didn’t matter whether the Jews were of a generation ago or a millennium ago — all were all his brothers and sisters.

And then there was the Holocaust. He always spoke about it.

Every Motzaei Shabbos, bochurim from the Novominsk yeshivah were invited to the Rebbe’s home for Melaveh Malkah. There, they were free to ask the usually very preoccupied Rebbe any question that might be on their mind. One boy mentioned that the Rebbe was known to be a great proponent of Holocaust education as part of the curriculum in frum schools. “Why?” the bochur asked. “Why does the Rebbe feel that it is so important to teach students about the Holocaust?”

The Rebbe was quiet for a moment, his eyes cast downward. Then his head jerked up and he virtually roared: “Because you are a part of Klal Yisrael and you must know what happened to your People seventy years ago!”

He didn’t want the children to merely know it. He wanted them to feel it as well. A longstanding custom of the Rebbe and Rebbetzin was that each Chanukah, they would order dozens of the most recently published Jewish book and have them inscribed and then given to each grandchild as a Chanukah present. One year, the book of choice was an in-depth documentary titled Witness to History by Ruth Lichtenstein, (publisher of the English-language Hamodia and renowned Holocaust historian). The book was one of her many efforts to memorialize the Holocaust, all of which were very much admired by the Rebbe. Rabbi Muller’s son Avrumi, an ambitious nine-year-old at the time, made it his business to read the entire book. Sometime later, the Mullers were visiting the Rebbe.

“Rebbe,” said Rabbi Muller, “I just want you to know that Avrumi finished the whole book!”

The Rebbe looked up, curious. “Really?” he said. He then turned to Avrumi with a serious expression. “Can I ask you a question?” His voice was uncharacteristically pensive. There was a moment of surprise mixed with tension. Was the Rebbe going to quiz this young child on the specifics of World War Two, Nazism, the Final Solution? The Rebbe leaned over and looked Avrumi in the eye. “Did you cry?”

Avrumi shook his head. “N-no,” he said sounding confused. “Well, then,” said the Rebbe, “you will have to read it again.”

Ich vil yetzt gebben a hesped oif Klal Yisroel!

The Rebbe remembered those tears and he wanted to ensure that they never be forgotten.

But it wasn’t just the modern-day Holocaust. The Churban Beis Hamikdash, as far as the Rebbe was concerned, was just as relevant and excruciating as if it happened today. On Tisha B’Av, tears would course down his face as he read Kinnos, and he would always say, “Until Mashiach comes, Klal Yisrael is homeless — we are sleeping on a park bench!”

Past and present, them and us. For the Rebbe, it was all the same.

The Rebbe was fond of saying that an appreciation of our history is actually a mitzvah. He would quote the pasuk in parshas Ha’azinu, “Binu shnos dor v’dor — and you shall understand the years from generation to generation,” and explain that “it is a mitzvah for us to learn our history, to understand how Hashem has related toward his People through each phase of our thousands of years of existence.”

The Rebbe would also quote the pasuk at the end of V’Zos Habrachah, describing how Moshe Rabbeinu climbed to the top of Har Nevo and looked out upon all of Eretz Yisrael “ad hayam ha’acharon.” It literally means “until the final sea,” But Rashi interprets the word “yam” as “yom” — “until the final day.” Moshe Rabbeinu’s gaze swept through all of time, and the Rebbe would bring this as proof of the importance of connecting to Klal Yisrael in its totality, encompassing all of time up until the Final Day.

And the Rebbe wasn’t just talking about academic study. He believed that a thread, first woven by the Avos and then interlaced throughout all of time, continues to guide us, linking us back to the reservoirs of spirituality that they dug, and to the divine blessings they achieved. In the recently published Volume II of Novominsk on Chumash (ArtScroll/Mesorah) — a collection of divrei Torah, hashkafos and stories expressing the Rebbe’s ideals, written by his close talmid Rabbi Yecheskel Ostreicher — it is cited how the Rebbe used this concept to explain a line in the first brachah of Shemoneh Esrehi: “U’meivi goel livnei v’neihem, l’maan shemo b’ahavah — and He brings a redeemer to the children of their children, for the sake of His Name, with love.” What evokes this specific love?

Said the Rebbe, this refers to a chain of love whose first link was held in the hand of Avraham Avinu. The chain of love that the Avos began, continued by Bnei Yisrael when they left Mitzrayim to go into the Wilderness, will reach its climax when Hashem ultimately redeems us, b’ahavah.

We are all links in that chain, said the Rebbe, a chain that forges an inseverable connection with our forefathers.

And its links will continue downward until the yom ha’acharon.

The Rebbe’s beis medrash. If the walls could talk, they’d share the secret of how to blend the simple with the esoteric

For Love of the Land

Moshe Rabbeinu’s eyes scanned straight until the final day. But the Rebbe liked pshat as well and the simple meaning of the pasuk “ad hayam ha’acharon” is that he stood upon a mountaintop, viewing all of Eretz Yisrael with the fiercest love, peering over every city, every river, every blade of grass, every grain of sand — until the final sea.

“As much as my father was a Klal Yisraedike Yid, he was also an Eretz Yisraeldike Yid,” says Reb Yisroel. The Rebbe’s love for Eretz Yisrael was legendary, a passion that seemed to envelop his entire existence.

The Rebbe would describe his first trip to Eretz Yisrael with great intensity. He had traveled together with his wife and his father, the previous Novominsker Rebbe. “When the speakers crackled and the pilot announced that they were entering the airspace of Israel, I began to cry,” the Rebbe said.

As described in Novominsk on Chumash II (parshas Shelach) the idea of airspace holding kedushah is sourced in a Gemara in Gittin: At that time I was learning the sugya of tumas eretz ha’amim, the laws of impurity that Chazal extrapolated for the area of chutz laAretz. The Gemara (Gittin 8b) says that the tumah of chutz laAretz is not limited to the ground; the air above it is tamei too, and someone who enters its airspace even without touching the ground is rendered tamei. Middah tovah merubah, I thought to myself — the measure of good always exceeds that of bad. If the air of chutz laAretz contaminates, how much more the air of Eretz Yisrael surely purifies!

Once the Rebbe composed himself, he stood up, looked out of the window and quoted the pasuk in V’zos Habrachah, “Umineged tireh es ha’aretz — And from across you will see the Land.” The Rebbe would recall how his father leaned over and said, “Don’t finish the pasuk!” (The pasuk ends, “v’shama lo savo — and there, you shall not go.”)

“I remember when my father came home from that trip,” says Reb Yehoshua. “I was a young child, around seven years old. He was on such a high, you couldn’t talk to him for weeks. Every Shabbos, he would repeat stories from that visit. One story he loved to share was how, on Erev Shabbos, my father and mother took a taxi to run an errand in Bayit Vegan. My father was in the car together with the driver, waiting for my mother to return. The driver was growing impatient and soon became agitated. He turned to my father and exclaimed ‘gam etzli Shabbat hayom (I also have Shabbos today)! My father couldn’t get over that line. He would keep repeating, ‘The taxi driver said gam etzli Shabbat Hayom!’ ”

The Rebbe always enjoyed pointing out subtleties in the siddur, gleaning important lessons from the most nuanced wording. In the Friday night zemer Kah Ribbon, there is a reference to Yerushalayim as the “karta d’shufraya.”

“Nu, what does this mean?” the Rebbe would ask those in attendance. If someone replied “a beautiful city,” he was falling into the trap. “Aha!” the Rebbe would say, “if that were true, it would say ‘karta d’shufrisa.’ Grammatically, the words karta d’shufraya does not mean beautiful city. It means ‘city of beautiful people.’ ”

Reb Yisroel tells of a time when the Rebbe was offered the opportunity to plant seeds on a farm in Moshav Komemiyus. The Rebbe of course accepted, and, filled with emotion, bent down to place a seed in the holy ground. “Suddenly,” says Reb Yisroel, “he stopped, stood up, and ran to get his gartel, and then, once properly attired for the mitzvah, proceeded to plant.”

While in Komemiyus, the Rebbe was also offered the chance to drive a tractor. The Rebbe sat behind the wheel, pressed the pedal, and plowed the land of Eretz Yisrael as tears flowed freely from his eyes.

“A day hasn’t gone by,” the Rebbe once confided in Rabbi Muller, “that I haven’t thought about Eretz Yisrael and the Yidden in Eretz Yisrael.”

Somehow, even as the Rebbe’s heart burst with so much love and so much pain and so much responsibility, there was one passion that magically seemed to supersede it all. “Several times,” says Rabbi Muller, “I would open the door to the Rebbe’s study. I would wait a moment, watching him bent over his Gemara and then venture a ‘hello.’ The Rebbe had no idea I was there. He was in a different world entirely.” The Rebbe would learn for hours on end, beginning before 4:00 a.m. and not closing his sefer until it was time for Shacharis.

“I was once staying at the Rebbe’s home for Shabbos,” recalls Rabbi Muller. “I went to a tish in Boro Park and returned home at 1:30 a.m. I opened the door and distinctly heard the voice of the Rebbe, saying Birchas haTorah.”

Reb Yehoshua notes that the burden his father carried on his shoulders might have been crushing, but “when he learned, he elevated himself above all the agmas nefesh.” The Rebbe always loved to learn, but he held a special place in his heart for a seder before Shacharis, and especially a pre-Shacharis seder on Shabbos.

“Nussi,” he once said to Rabbi Muller, “Rashi in the beginning of Shir HaShirim brings in the name of Rabi Akiva that all the sifrei Nach are kodesh while Shir HaShirim is kodesh kodoshim. And I say, that learning before Shacharis every day is kodesh, while learning before Shacharis on Shabbos is kodesh kodoshim!”

And if one couldn’t witness the sublimity of the Rebbe bent over a Gemara in predawn hours, there was another option. There is a minhag in the Novominsk chassidus that, on the night of Shemini Atzeres, following Hakafos, the Rebbe would enter the middle of the dance, holding a sefer Torah, even after all the others had been placed in the aron kodesh. The Rebbe would then read the chapter of Eishes Chayil in Mishlei. He would pause after every verse and offer an interpretation that was entirely novel, not shared by any of the previous rebbes.

The Rebbe cherished this sacred minhag and, sefer Torah clutched against his chest, eyes clenched tight, he would read each word of Eishes Chayil, explaining how these passages, written by Shlomo Hamelech so many years ago, are all allusions to the love between Hashem and Klal Yisrael, Klal Yisrael and the Torah, and Hashem and the Torah. And then the Rebbe would dance. And dance. And dance. And dance.

AT the closure of both Pesach and Succos, the Rebbe would host a Ne’ilas HaChag. He would share divrei Torah and sing some of the classical zemiros but then, he would sing a song that few had ever heard. It was a composition that the Rebbe learned from his father, an inheritance passed through the generations of his sacred dynasty.

The Rebbe would stand up and everyone would stand with him. They would hold hands and the Rebbe, with his eyes shut tight, would begin a most unique tune. It was something of a chant; it had a merry tone to it, with quick ups and abrupt downs but somewhere in its ebb and flow rang a barely audible bar that struck a sense of longing, pleading, desperate hoping.

The song was set to the hadran said at a siyum. But, in the place where the specific mesechta is mentioned, the name of the Yom Tov was inserted instead:

Hadran alach Chag Hamatzos, v’hadrach alan Chag Hamatzos. Daatan alach Chag Hamatzos, v’daatach alan Chag Hamatzos — Return to us Chag Hamatzos and we’ll return to you, Chag Hamatzos. Our thoughts are with you, Chag Hamatzos, and your thoughts are with us Chag Hamatzos.

Lo nisnishi minuch Chag Hamatzos, v’lo sisnshi minun Chag Hamatzos — We will not leave you, Chag Hamatzos, and you will not leave us, Chag Hamatzos.

Lo b’alma hadein v’lo b’alma d’asi — Not in this world and not in the world to come.

Three years ago, Novominsker talmidim did not sing that song. The Rebbe had passed away just two days before Yom Tov, his neshamah returning to where it was most comfortable. A terror-gripped nation heard the news and grappled to balance fear with grief. That Pesach, they stayed home, chained by mandatory isolation, trying to make sense of it all. But chains, they all knew, were the Rebbe’s specialty.

Mir darft zich ibbershtrengen! A yid darft ibbershtrengen!

And so they struggled and jostled and wrestled free from those chains of bondage and turned them into the chains that the Rebbe knew best. The ones that link us back to Avraham Avinu.

And with chains of eternity they danced, alone. And they sang.

Hadran alach heilige Rebbe V’hadrach alan heilige Rebbe.

Daatan alach heilige Rebbe V’daatach alan heilige Rebbe.

And the years will go by, but the dance will continue. Because deep down, they know that the Rebbe never left them.

Lo b’alma hadein v’lo b’alma d’asi.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 956)

Oops! We could not locate your form.