Winning moves

| March 21, 2023Chess master Josh Bowman has a thousand yeshivah kids from around the country in his Chess Chevra, where they’re learning to think clearly while playing the world’s oldest game

Photos: Naftoli Goldgrab

They control kings and queens and manipulate entire armies, but instead of suiting up in battle gear, these pint-sized female warriors wear gray pleated skirts and light blue uniform polos as they hone their contemplative skills and zoom in for the win during the chess class at Brooklyn’s Bnos Leah Prospect Park Yeshiva.

There’s a definite buzz in the air as I walk into the school’s chess classroom with Josh Bowman, whose Chess Chevra program is currently teaching the age-old board game in 17 schools nationwide. The program also offers online global tournaments for those who dream of becoming accredited masters of the game.

Even as the girls sit listening attentively to Chess Chevra instructor Marfa Esaulova, known to her Prospect Park Yeshiva students as Morah Marfa, it’s clear that students are itching to start battling on the green and tan vinyl chess mats laid out in front of them. Bowman’s eyes survey the room as Esaulova demonstrates an opening move known as the Queen’s Gambit — sacrificing the queen’s pawn to gain better control of the center of the board — nodding appreciatively as one girl offers a solution to the problem posed to the class.

As the games begin and students face off against each other, Bowman’s eyes light up as he moves from board to board, quizzing the girls about the three ways to get out of a check situation, suggesting potential moves and exclaiming animatedly as one player loses her queen in an ill-fated maneuver. Without a doubt, Bowman is a long way from his first encounter with chess, when he was nearly the same age as these fourth-graders, his journey to launching Chess Chevra spanning many years and thousands of miles.

Josh Bowman, who had earned the rank of national master during his off time in yeshivah, ultimately came full circle, combining his love of chess with his two other passions — education and the Jewish community. Oddly enough, it was the pandemic that paved the way for Bowman to launch his career, the realities of the lockdown prompting him to start teaching chess on Zoom.

“It was at the very beginning of Covid, when you couldn’t go out at all, and I reached out to someone in Philadelphia whose kids had taken chess with me previously and asked him if he wanted me to give them lessons on Zoom,” recalls Bowman. “He asked if we could turn it into a group lesson, since his kids hadn’t seen their friends in three weeks.”

That first 30-minute-long class included six children from the same neighborhood, and it went so well that Bowman looked for a way to keep it going. He realized that parents were actively seeking ways to keep their kids occupied, so he put the word out on various platforms and asked friends to spread the news as well.

“Everyone has a cousin or a friend somewhere, and my network started expanding,” says Bowman. “We went from ten to 60 kids very quickly. There were no camps that summer, and people needed something to do.”

As the pandemic continued, Bowman’s phone kept ringing with requests for lessons. While originally Chess Chevra’s online lessons had been formed as clusters of friends, neighbors, or family members, the quickly-growing student body had to be categorized based on age, level, experience and gender. With so many students slogging through the 2020-21 academic year in Zoom school, Bowman’s online chess classes were much better suited to a virtual platform, and a welcome change of pace for lockdown-weary kids yearning for positive outlets.

As the world began reverting back to a less restrictive lifestyle, Bowman realized that Chess Chevra also needed to pivot. He used his newfound marketing network to search for teachers to accommodate the many requests for chess classes that were coming in. By the time the new school year rolled around, Chess Chevra was offering in-person classes in eight different schools in New York City, Monsey, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Boston, and Los Angeles. Schools were starting to realize that the game taught students to focus, plan ahead, and consider the consequences of their actions.

“The biggest challenge in this generation, for children and adults, is that there are so many bells and whistles always buzzing, which creates a desire to act impulsively,” explains Bowman. “We try to get them to slow down and to make careful, thought-out decisions and avoid the impulsivity that always leads to careless mistakes.”

A Kew Gardens Hills resident, Bowman estimates that Chess Chevra has taught nearly 1,000 students, 95 percent of whom were children. He does his best to visit each school at least once, despite the distance involved, going to classes in Skokie, Silver Spring, and Los Angeles. For the current school year, Bowman has 20 teachers giving classes in 17 schools throughout the country, in addition to private virtual lessons, with students ranging from pre-1A through high school.

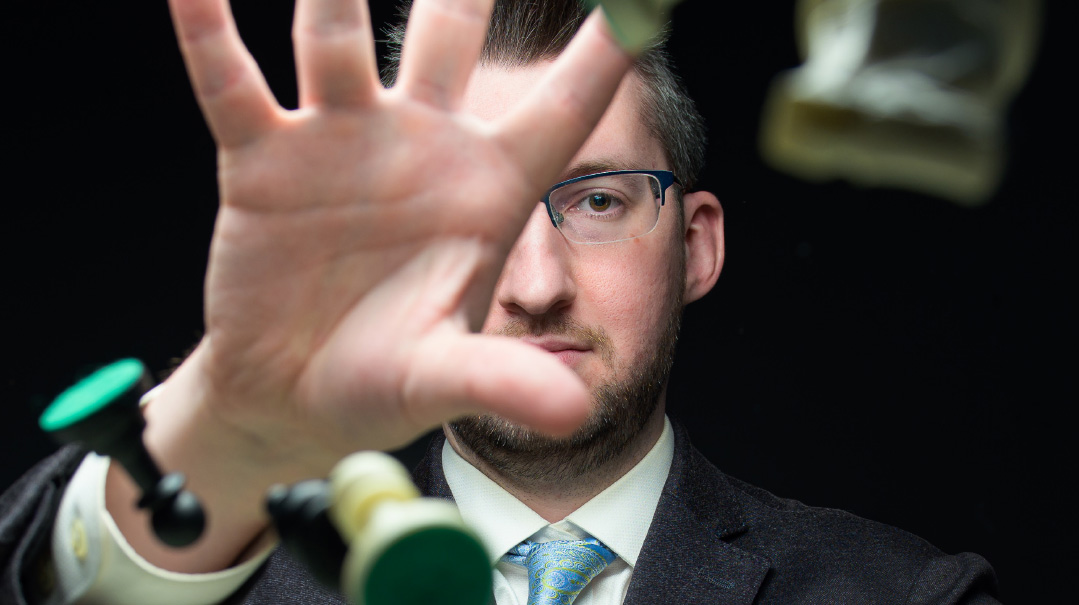

Josh Bowman challenges a student at an in-school competition. By the time the school year began, Chess Chevra was teaching kids to focus, plan ahead and consider the consequences of their actions

Prospect Park Yeshiva is one of four all-girl schools involved in the Chess Chevra program. It is Bowman’s only participating school where chess is a required subject, not an elective or an extracurricular activity. BLOPPY (Bnos Leah Prospect Park Yeshiva), as the school is also known, incorporated chess into the curriculum seven years ago so that students could learn to play without burdening parents with additional car pools or fees. The program was taught by National Master Oleg Frenkel for several years, and Prospect Park Yeshiva’s girls fared well when they competed against seasoned players in citywide all-girls chess tournaments. Post-Covid, for the 2021-22 school year, the school made the move to Chess Chevra, with Esaulova stepping in to teach the class both this year and last.

“When you meet the kids for the first time, they don’t even know how to move a piece, but after a while they learn and they can explain what they do, why they do it, and the way they do it,” says Esaulova. “Now they know how to play professional chess and how to speak chess language — they are part of the chess community, and they are growing incredibly rapidly.”

Students have reaped important benefits from learning to play chess, notes assistant dean Rabbi Akiva Kelman.

“Chess challenges the mind,” says Rabbi Kelman. “It works wonders with children who otherwise have trouble sitting still and paying attention. It teaches kids how to think clearly and strategize, helping them succeed in all of their subjects.”

Shattering the illusion that chess is a boys’ game, photos of the all-time greatest female players are taped in a row on the classroom wall, as is a list of ten things to remember when starting a game. With the decibel level rising as the games progress, it’s clear that the girls are all in. The thwap of students hitting the chess clock that times their moves ratchets up the energy in the room even higher.

“I like to play chess and learn new moves,” observes nine-year-old Shaindy Kelman, who has been taking chess since second grade and enjoys having an edge when she plays at home against her brothers. “The chess clock is cool and it makes the game competitive. It’s nice to have a break in the day to play chess and not just sit at a desk all day.”

Naturally, there are also plenty of boys participating in Chess Chevra programs. At Yeshiva Derech HaTorah in Flatbush, chess is offered as part of an after-school program for second- through fifth-graders. This year marks the first partnership between the yeshivah and Chess Chevra, and general studies principal Yehuda Goldstein is already seeing how maneuvering pieces around the board is helping students reach their full potential, both inside the classroom and out.

Watching instructor Abe Cytryn demonstrate a challenge on an easel-mounted chessboard, it’s not lost on me that the boys in his class could be playing video games once their school day has ended. And while Cytryn needs to occasionally remind students to raise their hands and stay seated, their joy at seeing captured pieces piling up is unmistakable. While Cytryn roams about the room, helping students make the most of each move, Bowman sits down with a top player, challenging him at every turn and complimenting him enthusiastically every time he captures a piece.

“It is proven that playing chess, especially at a young age, gets people to look at problems in a very different way,” observes Cytryn, who has taught his colleagues and his grandchildren to play chess. “It almost anti-ADD, because you have to really focus. If you get distracted, you lose your place, so chess forces you to pay attention.”

Cytryn, who also teaches another Chess Chevra class at a Manhattan Beach school, notes that the game has been enjoying a surge in popularity in recent years.

“A lot of people discovered chess during Covid,” remarks Cytryn. “It has really taken off in a big way, with the Internet giving people the ability to play against people all over the world.

With Covid getting people accustomed to doing business and learning over the Internet, Chess Chevra has the ability to span thousands of miles. Its ongoing online chess tournaments have brought players together from all over the globe. The most recent tournament, held in February 2023, had 105 players ranging in age from six to 41, with players in each section sorted according to their levels.

Staging a competition that can pit people of disparate ages against each other might seem odd, but Bowman notes that players are ranked on their ratings, not on their ages. One eight-year-old from London playing Chess Chevra’s February tournament competed mainly against teenagers, and despite the age difference, he won three out of four of his games, tying for third place in his section.

With participants hailing from all across the United States, Israel, Canada, the United Kingdom, and South Africa, just scheduling a tournament can be tricky.

“The difference in time zones, combined with the fact that most yeshivos are in session on Sundays, the day we typically hold our tournaments, makes it tough to find a time that works well for everyone,” says Bowman. “In the early evening in Israel and South Africa, American boys are still in yeshivah, and by the time the Americans get home, it is already quite late in Israel and South Africa.”

Having already run five worldwide tournaments for men and boys, Chess Chevra is hoping to hold its first tournament for women and girls in the near future. As a veteran of hundreds of tournaments, Bowman knows firsthand how valuable they are, and Chess Chevra stages smaller in-person tournaments in its schools.

“Tournaments give people something to get excited about, look forward to, and prepare for, putting into practice everything they have been learning,” observes Bowman.

Chess Chevra’s worldwide tournaments gives instructors a view into how their students are faring. Students can review their matches with instructors afterwards to take pride in key moments and identify where there is room for improvement. Tournaments also provide Chess Chevra members with an opportunity to come together, bridging the miles with a competition that focuses on both skill and fun.

“They get to compete with players from around the world in different sections, based on age and level, creating a sense of community by being part of something so large, and that is where the ‘chevreh’ of Chess Chevra comes out,” says Bowman.

Josh with chess coach (and math teacher) Abe Cytryn. “It’s almost anti-ADD, because you have to really focus. If you get distracted, you lose your place”

While Chess Chevra has evolved into a full time job, Bowman doesn’t allow it to consume his entire life. He also does SAT and college essay tutoring, in addition to learning every morning and some nights at Yeshiva Chofetz Chaim in Queens. Bowman’s kallah, Rachel Gilder of White Plains, doesn’t play chess at all.

Bowman’s favorite part of Chess Chevra is connecting with people. He has met students and their families at their homes in Baltimore, Boro Park, Har Nof, Kiryat Moshe, Ramat Beit Shemesh, and Maaleh Adumim, even surprising one student while on a trip to Israel by showing up at his bar mitzvah in Telzstone.

Still, his most heartwarming Chess Chevra moment occurred in the program’s debut year, when two nine-year-old boys — one from Cleveland and another from Staten Island — bonded over a shared love of the game.

“They met in chess class over Zoom and, through their mothers, they were able to connect outside of chess class,” says Bowman. “It touched my heart to hear how the boys had been speaking regularly over the phone and were calling to wish each other happy birthday.”

Because the vast majority of Chess Chevra’s students are young children, Bowman places a special emphasis on making the game appealing and enjoyable. His instructors begin their training by watching him teach, and he focuses on making sure that they explain things on their students’ level while keeping the lessons fun, warm, and engaging.

“We want instructors to keep it exciting by conveying the drama of a chess game, those turning point moments in a game where we have to say ‘wow!’ ” explains Bowman.

Now a national master, the Los Angeles-born Bowman was a deep thinker even as a kid. When he was in third grade, he saw a group of youngsters playing chess and was intrigued. He taught himself the rules of the games using a basic chess set and a lighthearted book titled Every Great Chess Player Was Once A Beginner. His early matches against family and friends were less than successful, but he kept reading up on chess strategy. Before long, he was on the winning end of every game. He continued honing his skills and his drive after the family moved the next year to Ambler, a small town on the outskirts of Philadelphia.

“A lot of people have this stereotype of old men sitting around the fire playing chess, but the truth is that youth is actually an advantage in chess,” says Bowman. “Of course, you have to be old enough to grasp the game, but you have to have the physical stamina to sit there for hours and not get tired. Your mind has to work very fast, and you have to think with a lot of precision, without making mistakes.”

Still, Bowman readily acknowledges that he often fell victim to the three-hour cumulative time limit enforced in chess tournaments.

“I was learning how to think as a kid, and the problem is that you can only play chess well if you know how to think, which you only learn by going slowly and thinking things through,” says Bowman. “I lost many a game on time, but I actually saw that as a good thing, because I was trying to find a good move instead of rushing.”

Bowman has employed that strategy throughout his life. Raised in a traditional Jewish home, Bowman connected to Torah Judaism as a Stanford University student, through the Meor campus kiruv program led by Rabbi Ephraim Kamin in the Bay Area. Drawn in by Shabbat dinners and a learning program called the Maimonides Fellowship, Bowman’s analytical mind had him asking all the right questions.

He wasn’t put off by a freshman year Birthright trip to Israel that he found lacking — “We went to the Kotel for only five to ten minutes, and a lot of the kids only had a Jewish dad” — and continued posing insightful questions to rabbis of all stripes, inching him closer and closer to Orthodoxy. He soon went back to Israel, this time on a more meaningful Meor trip, which he followed up with five weeks at Ohr Somayach.

After Bowman graduated Stanford, he set his sights on loftier goals, participating first in the Lakewood Fellowship Program and then spending four transformative years at Machon Shlomo in Har Nof and later in Rabbi Barry Klein’s chaburah in Beis Yisrael. During that time he acquired a solid foundation in Torah learning and honed in on a career choice that resonated with him — education.

“I had been tutoring kids for their SATs to pay my way through college and yeshivah, and I realized that I liked teaching, but I didn’t see myself as a classroom teacher,” says Bowman. “I even thought about becoming a rabbi, but I realized that I really wanted to be in some kind of educational setting.”

Machon Shlomo dean Rabbi Beryl Gershenfeld was on board with Bowman’s plan, suggesting that he enhance his résumé by obtaining a master’s degree in education through Harvard University’s Mind, Brain, and Education program.

“I went into the master’s program knowing that I wanted to run some kind of an educational company, but I became less passionate about SAT tutoring because it is a very saturated market, and its mission of learning strategies to get into a better college just wasn’t resonating with me,” explains Bowman. “I had gone to elite colleges and had lost the idealism, because I saw they were more about having fun and making money than anything else.”

Bowman remains in close touch with the rebbeim who transformed his life —Rabbi Gershenfeld, Rabbi Kamin, Meor’s Rabbi Yehoshua Styne and Rabbi Klein. Bowman credits his parents Bill and Barbara Bowman for encouraging him in his pursuit of chess, investing in countless lessons and tournaments throughout his childhood. He admits that he never dreamed he could turn his passion for chess one day into a full-time career. Never has the need for chess instruction been more keenly felt, when the temptation to click, act, and speak quickly is everywhere.

“Chess Chevra’s number one goal is to get people, children especially, to slow down and restrain themselves from acting impulsively, and instead, thinking carefully through the consequences and only moving when they have truly thought through the situations and outcomes,” remarks Bowman. “We believe that this prudence and inhibitory control can help students in their learning, academics and even their relationships.”

An Ancient Game

Chess is believed to have evolved from the Indian game of chaturanga around the year 600, but its exact origin remains unknown, and theories that it was invented centuries earlier by Shlomo Hamelech are as intriguing as they are unlikely. Its long history in the Jewish world includes a Talmudic reference in Kesubos to a game that Rashi describes as chess, at least according to some opinions, with additional mentions in Sefer Chassidim, the Kuzari and Ibn Ezra’s poem “Charuzim,” which contains the oldest-known description of the game’s rules.

The Rambam took a less enthusiastic view of chess in his commentary on Mishnayos, noting in Sanhedrin that professional chess players could not recognized by a beis din as credible witnesses, and halachic sources spanning several hundred years espoused differing views regarding the game’s permissibility on Shabbos.

Jews have long been disproportionately represented in the annals of chess championships, up through contemporary times. Israel is currently ranked 15th worldwide by the International Chess Federation, a relatively high standing given its small size, and Be’er Sheva’s percentage of chess grandmasters among its populace is the highest of any city in the world.

“Don’t Play Hope Chess”

Having spent years immersed in chess’s many nuances, Bowman still believes that the most important tip he can offer is one he learned from National Master Dan Heisman, his boyhood chess teacher.

“Play real chess, not hope chess,” advises Bowman. “Hope chess is where you make a move that isn’t objectively the best, but you set a trap and just hope the other person doesn’t notice. But if they do notice, and respond correctly, you will be in an inferior position.”

Instead, Bowman recommends playing “real chess” — making the objectively best move, based on calculating the consequences if your opponent does the same.

“This is a simple but deep point that many children and adults alike don’t yet chap,” observes Bowman. “Understanding and internalizing this point is a game-changer for the way we make decisions, in chess and in life.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 954)

Oops! We could not locate your form.