Why Are Prices Going Up?

| August 23, 2022Inflation is when the buying power of a dollar diminishes, and prices rise all over — two sides of the same coin

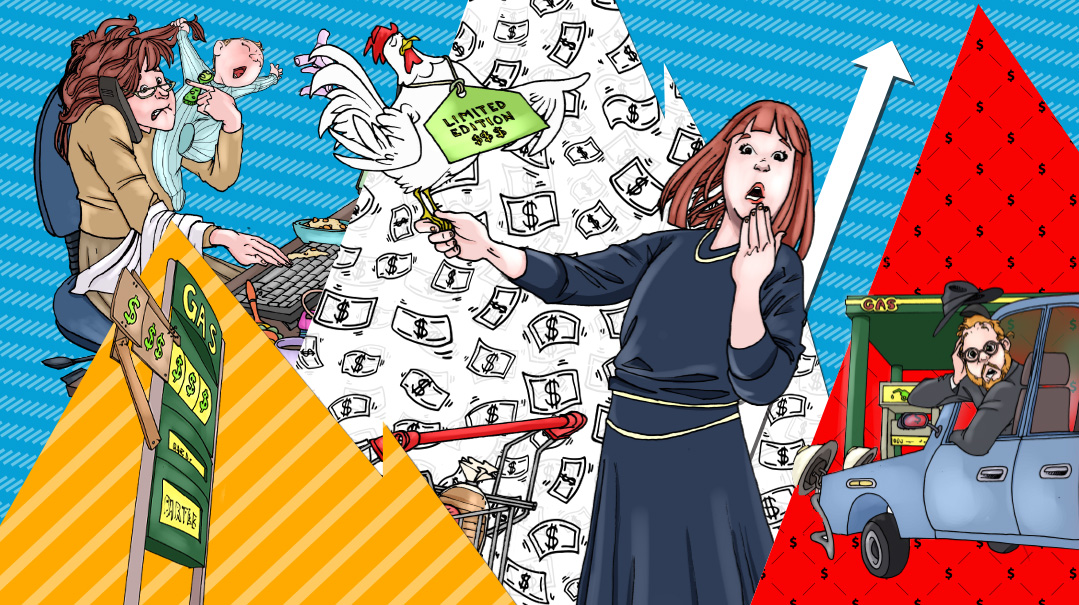

Illustrations: Dov Ber Cohen and Yosef Haim Lev

With reporting from Refoel Pride

Part 1

What exactly is inflation, anyway?

Inflation is when the buying power of a dollar diminishes, and prices rise all over — two sides of the same coin.

How do you measure inflation?

Economists measure the rise in prices using the Consumer Price Index, which rose 8.6% in one year — the most in 40 years. Fuel oil was up 106.7%.

Regular people measure inflation by their bank accounts. When it takes a lot more money to buy the things you usually purchase, you can blame inflation.

How did this happen?

Well, things that are rare tend to be more precious than things that are common. Think gold versus aluminum. And dollars have gotten a lot more common recently.

This happened because something called the “money supply” has increased dramatically over the last two years. (Sorry, brief economics lesson.)

The money supply is pretty self-explanatory: It’s the total volume of dollars held by the public at any point in time. The money supply is controlled in the US by the Federal Reserve. (You’ve heard of them. Just look at any dollar in your wallet, you’ll see their name on it.)

The way the Federal Reserve changes the money supply is beyond the scope of this article. (You’re welcome.)

What’s important to know is that at the end of 2019, the money supply stood at $15.3 trillion. Two years later, at the end of 2021, it had increased to $21.8 trillion — an increase of 42%, which was really unprecedented in history.

When the pool of all money is expanding so much, it makes each individual dollar worth less, as a shrinking fraction of a growing whole. That means a dollar at the end of 2021 is worth less than a dollar at the end of 2019. So you have to pay more 2021 dollars to get the same thing you got in 2019.

Okay, but… I was told it was due to shortages?

When the value of money is plummeting, companies are reluctant to commit to long-term plans, until the problem is sorted out. That means older equipment isn’t replaced, new factories aren’t built, and new employees aren’t hired. That leads to constraints in production.

But the current shortages had many other causes as well.

Once upon a time, a long time ago, in a faraway land, there was a pandemic.

Factories closed and people stopped working. This led to a shortage of goods and services. For example, the closure of computer chip factories led to a shortage of the chips used in computers and cars. But with people now avoiding mass transit and working from home, the pandemic also spurred higher demand for computers. The pandemic both cut off supply and created a greater demand.

Here’s another example. Pandemic-related factors initially created a surplus of livestock, which forced some farms to resort to chicken depopulation. Eventually, demand rebounded, but later waves of new variants took their toll at various points in the supply chain.

So what’s the deal with the supply chain thing I keep hearing about?

It wasn’t only the factories that slowed down. The ports also did. First the flow of goods from China decreased (remember, their factories were closed and their workers were in lockdown), so fewer containers hit the ports in the US. Then the pandemic reached the US, which put all the local dockworkers in quarantine. There was no one to unload the containers. New goods were reaching consumers much more slowly, not necessarily keeping pace with consumption.

But that labor shortage was temporary! No?

No, actually. Even when the economy reopened and people were able to go back to work, many people chose not to. Some were receiving unemployment benefits that made it unnecessary for them to work. Others had adjusted to the pandemic by opening businesses or creating income in other ways that did not require them to return to their previous work lives.

So the labor shortage lives on.

It slows production and transportation of goods, which adds to the shortages.

It’s tough to be a consumer, what can I tell you?

But wait! What about the stimulus checks?

What about them?

When the government issued the stimulus checks, people were thrilled to spend them, and demand for goods skyrocketed. But this was driven by the government’s largesse, not because the economy suddenly became more productive. This was part of the growth in the money supply that had no relation to the value of the economy. See above. But the pandemic is over!

Yeah. It ended exactly on the day the war in Ukraine started. Crazy how these things happen, right?

I feel like I don’t want to hear this.

You can stop reading here. I’ll never know.

You have to understand what the conditions were. Just like Covid initially lessened the demand for consumer goods, it also created a plunge in energy consumption. People just weren’t really going anywhere or doing anything.

But the world started to recover, and demand increased. Plus there was the long, cold winter. Energy supply didn’t meet the demand, causing conditions ripe for crisis.

But what does the war in Ukraine have to do with this?

Russia produces about 12% of the world’s oil supply, which is used to make gasoline. The US created sanctions that made it complicated to clear Russian oil transactions through Western banks, reducing supply — just when demand bounced back to pre-pandemic levels.

(It’s not only the war. Oil prices are rising in general because the federal government killed the Keystone pipeline project and has imposed regulatory barriers that have made fracking impractical and unprofitable.)

And when supply can’t meet demand... prices go up.

Ukraine is also a significant producer of wheat, barley, corn and other important of the world’s food supply. The war has affected both production and shipping, and wheat prices have soared by 60%.

Isn’t there anything anyone can do?

The government is trying. I don’t know if that makes you feel better.

They’re raising the interest rates, which will reduce the money supply over time. Companies will borrow less money, and people will sock away more savings. Fewer loans and more savings take dollars out of circulation, so the money supply goes down. But it’s not an immediate effect, it takes time.

How in the world will a higher interest rate make anything better?

Eventually, the money supply will drop enough, and the economy will grow enough (albeit more slowly) to where the two are back in equilibrium. The value of dollars will have adjusted to the value of the economy. Then these huge fluctuations in prices we’ve been seeing will settle down.

Put a little differently, by raising interest rates, the government makes things more expensive. It’s also more expensive to borrow money. Fewer people will buy things, supply will rise, and prices will fall.

So how is all this going to end?

I’m not sure. The psychic readers haven’t come back to work since the pandemic ended. But I’ll tell you what happened in previous times of inflation.

The period after World War II had similar shortages, like cars and appliances, because the government ramped up spending on production for the war effort. Factories were making things the government wanted, like planes, ships, and tanks, instead of things consumers wanted, like Chevys and refrigerators.

Also, as there was following the pandemic, there was a sudden outburst of pent-up demand. So supply was low and demand was high.

Back then, it took two years of a booming economy to bring everything back into balance, until the supply chain normalized and demand leveled off. So hopefully the period we’re going through is transitory also.

Part 2

Frumenomics

The frum community is not impervious to any of the global or economic factors at play, but the results are as unique as our community.

I live in Lakewood. When I registered my baby for two-year-old playgroup next year, the morah told me she had raised her rates $100 a month since I sent her my last kid a year ago. But at least she’s working. I couldn’t find a babysitter for my newborn, so I have her home with me while I work. It’s totally dysfunctional, and I’m working way fewer hours than I used to when I didn’t have a baby home with me. I end up working a lot at night, which is very hard — I’m not a night person. I have teenagers who need me then, I have housework and phone calls to take care of, and I get in a bad mood when I know that I have so much work still to do. I just kept telling myself it’s temporary, except there’s no end in sight. The other thing I keep telling myself is that if I’m not paying a babysitter, that’s $500 less a month that I need to earn. But having my baby home cuts my earning power by much more than $500 per month. So my income has gone down while prices are going up…

I commute, and I fill up three times a week. It costs about $75 a tank — you do the math. It’s totally unsustainable. Maybe I should stop going to work. I’m kidding. I think. No road trips this summer, that’s for sure. I used to think a Tesla was a luxury, but it doesn’t feel like that anymore. Not that there are any new cars to buy even if I wanted one…

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 925)

Oops! We could not locate your form.