Where Meron Lives On

The heartrending test of loss without closure or memorial

IN

a tranquil corner of Ramat Beit Shemesh, the tragedy of Meron hasn’t ended.

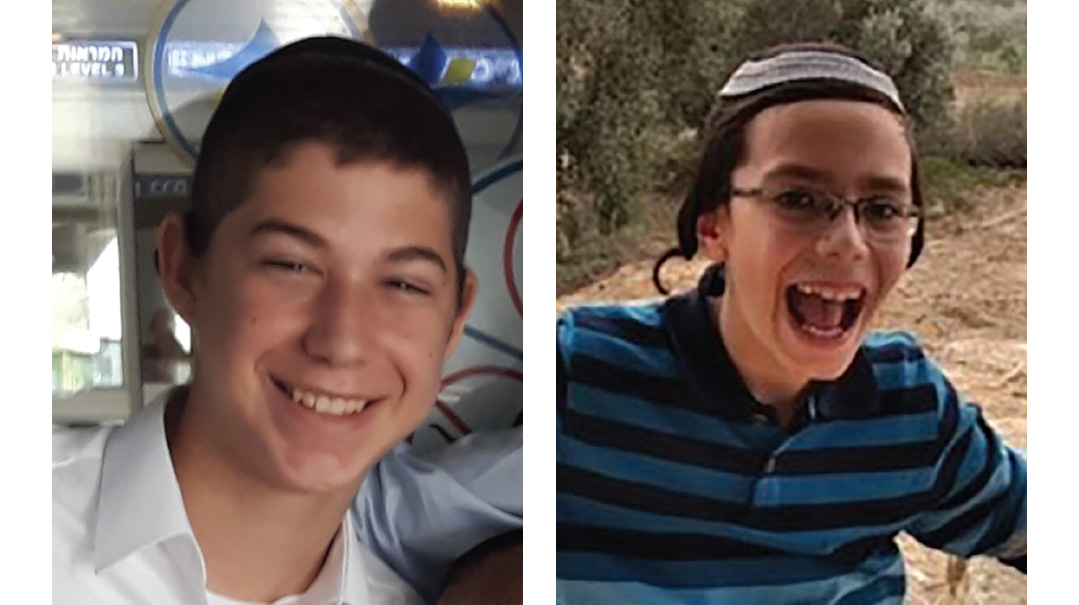

It’s the bedroom of Yossi Reit, one of two teens who entered the tunnel of death that fateful Lag B’omer night and have spent the years since in the half-life called a coma.

Now 17 years old, Yossi is physically present. Outwardly healthy, he breathes unaided, but he can’t move. His once-sparkling eyes are dull; what goes on in his mind is impossible to know.

The Meron tragedy wore different faces. There were the 45 kedoshim — the pure souls who lost their lives minutes after a spiritual high. There were those who struggled to recover their health after the deadly crush.

But for Dr. Yechiel and Michal Reit, along with the parents of 14-year-old Elazar Berger, Dov and Reumah Berger, Meron meant something else: a son who came back from the brink, but has never really returned.

Grief didn’t strike the Reits straight away. Yossi was a late arrival to Meron on that Lag B’omer. A talmid of Yeshivas Ohr Torah in Beit Shemesh, he had really wanted to experience the celebrations, and so, that Thursday evening, he joined several of his friends on the bus up north, and headed for the Toldos Aharon hadlakah.

On the way back from a wedding, the Reits got a phone call from Yossi. Due to the background noise, it was hard to make out much from the call. But Yossi sounded happy, so his parents went to sleep.

They were woken by a phone call from Yossi’s sister with the news of an unfolding disaster in Meron. Along with thousands of others, their attempts to make contact with their son was frustrated by the collapse of the cell phone signal.

Close to four in the morning, the phone rang. It was Yossi’s number, and everyone breathed a sigh of relief.

But as soon as he took the phone, Dr. Reit knew that something was badly wrong. It was a Magen David Adom paramedic on the line. He was evacuating an injured teen who carried no ID, but whose phone carried a contact labeled “Abba.”

The Reits sped to Rambam Hospital in Haifa, where Yossi — who was tall for his age — lay in the regular ICU. Instead of the smiling son they’d seen the previous afternoon was a boy now fighting for his life.

After 52 days in the ICU, Yossi had come back from the brink of death. He was operated on in Schneider’s Hospital in Petach Tikvah, after which he was able to breathe without a respirator.

At that point, the Reits still thought their son — whose physical recovery was a medical miracle — would make a full recovery in mind as well.

But after a stint in the Alyn Rehabilitation Hospital in Jerusalem, that hope was dashed, and Yossi was brought home, his once-infectious spirit and lively smile masked by his comatose state.

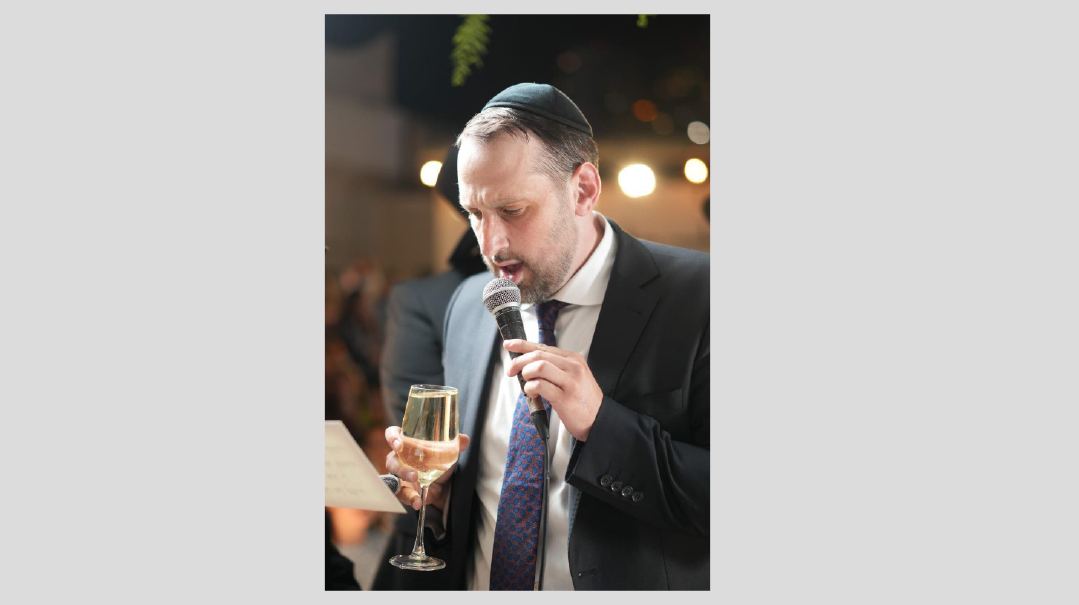

In an interview with Mishpacha’s Hebrew edition last year, Dr. Reit spoke movingly of the learning sessions that he once enjoyed with his son.

“I loved Yossi very much. I loved to learn with him. Although I wasn’t able to learn with him all week, I don’t work on Thursday, so we had a chavrusa each Thursday. In the evening, I would come to his yeshivah and we learned the halachos of tefillah and tefillin, because Yossi felt that he was not as strong in the practical halachos. For me, it was a special experience to see how my son was developing, growing, and how his personality was being built.”

Dr. Reit also spoke of the duality of emunah in the aftermath of tragedy.

“We know how to be grateful,” he said. “Hashem decreed that Yossi should be hurt, and it could have happened to him anywhere. There are children who are born with chronic illnesses, and their parents struggle from the time they’re born. With Yossi, Hashem postponed our struggle. We enjoyed 15 years, during which he filled us with light and joy. Shouldn’t we be grateful for that?”

And yet, he admitted to being daunted by the scale of the challenge. “Do I feel like I have grown and become stronger as a result of this blow? It’s hard to know, because it’s hard. It’s hard and painful.”

In the context of mourning, the admission of that duality is oftentimes missing. The struggle to reconcile intellect and emotion, acceptance and hurt, can take years to resolve.

Yet duality is exactly what halachah recognizes is the natural reaction to tragedy, even for the ma’amin.

It’s why, explains Rav Moshe Feinstein, there’s a contradiction at the heart of our practice of aveilus. On the one hand, the Gemara tells us that we thank Hashem for the bad like we do for the good. Yet when a person loses a loved one, he doesn’t say hatov v’hameitiv like when winning the lottery. Instead, the brachah of Dayan ha’emes is substituted.

The dissonance, says Rav Moshe, is because even for the greatest believer, the emotion refuses to accept the truth of what the intellect knows.

Halachah is cognizant of those frailties, that we’ll never emotionally embrace suffering in the same way we celebrate joy; acknowledging the Dayan ha’emes is a lofty level, because we’re not superhuman.

That’s why in the apartment in Beit Shemesh in which Yossi’s parents are faced each day with the what-ifs of untraveled roads, while their son lies wrapped in silence, there’s greatness.

For theirs is the heartrending test of loss without closure or memorial.

Join thousands of people all over the world in adding the names Yosef Ezriel ben Chaya Michal and Elazar ben Reumah to your tefillos.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 959)

Oops! We could not locate your form.