When Zaidy Was No Longer Young: The Story of the Home of the Daughters of Jacob

The incredible story of New York's first shomer Shabbos, fully kosher nursing home, its colorful residents, and the legendary characters who built and sustained it

Photos: History of the Home of the Daughters of Jacob, YIVO, YU Archives, Kedem Auctions, Library of Congress, JewishData.com, New York Public Library, DMS Yeshiva Archives, various newspapers, AKG-Images

T

here’s no bigger pitfall for a historian than the proverbial rabbit hole. Taking the bait means that suddenly, the two late-night hours I’ve allotted to completing a story that’s been burning a hole in my computer for the last six months… have now disappeared.

A dozen books are piled up on my desk, my computer has 43 different windows open, and I’m desperately working the phones, trying to reach someone who can decipher a complex Yiddish passage for me at this ungodly hour. My training tells me to do everything in my power to avoid these distractions, however tempting they may be. But this time — and it’s not the first — I succumb. I pour myself another cup of Coke Zero and dive in headfirst.

It’s certainly not a subject I ever expected to pursue. Straightaway, I realize that few writers, researchers, or historians would have plumbed this deep abyss — for good reason. The primary sources are anemic, and the secondary sources seem dubious at best. Still, this story has a charm and an aura such that I cannot let go. It’s a story that brings alive forgotten Jewish life in New York in the post-Rav Hakollel era. It’s Uptown meets Downtown, shtetl meets society, and showcases the Jewish spirit of giving at its finest.

Transfixed, I don my imaginary Magical Yarmulke and transport myself to a world where Shmuel Kunda outpaced Shalom Aleichem and sour pickles are the only remnant. It all started with an oddly compelling 1907 article in the long-defunct New York Herald:

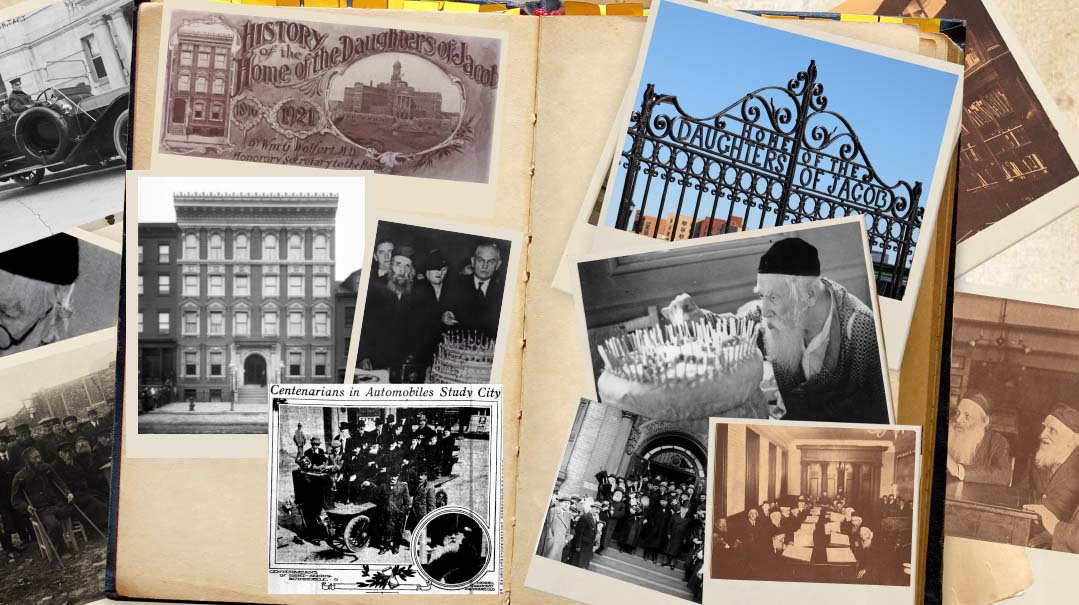

The inmates of the Home of the Daughters of Jacob, 301 East Broadway, not one of whom is under seventy years of age, took their annual outing Sunday in three big sightseeing automobiles. Loaded down with fifty-five old people, the cars swung around the Flatiron Building and down Broadway startling the occupants of other vehicles and surprising the casual onlookers.

In the front seat of the first automobile alongside the chauffeur was Mrs. Esther Davis, who has passed the 112-year mark, while behind her was Mendel Diamond, who says he is fast approaching 100 years. There was also Baruch Weber, 85 years; Nathan Sher, 96 years; Sarah Gottherman, 92 years, and Alter Silverman, 95 years.

The excursion started at the home and went over to Broadway and up that thoroughfare, then up to 110th Street, and back home. Many of the inmates of the home had never been uptown, and their amazement at the sight of the tall buildings attracted no end of attention. The Flatiron Building proved a magnet, and the chauffeurs were obliged to stop and allow them to enjoy the sight. Broadway also enjoyed the sight of the old men, with their high hats and flowing white beards. The crowd became so large that it was found necessary to send several mounted policemen along with the outing. When Sixty-Eighth Street was reached, the machines were driven to 323 East, which is the home of Mrs. Annie Joseph, who is one of the directors of the home. She had a luncheon already prepared for the old people. The old men received their allowance of schnapps to keep out the cold, and then they went to the home of Mrs. Abraham Dworsky, at 53 East Ninety-Third Street, President of the (Daughters of Jacob) home.

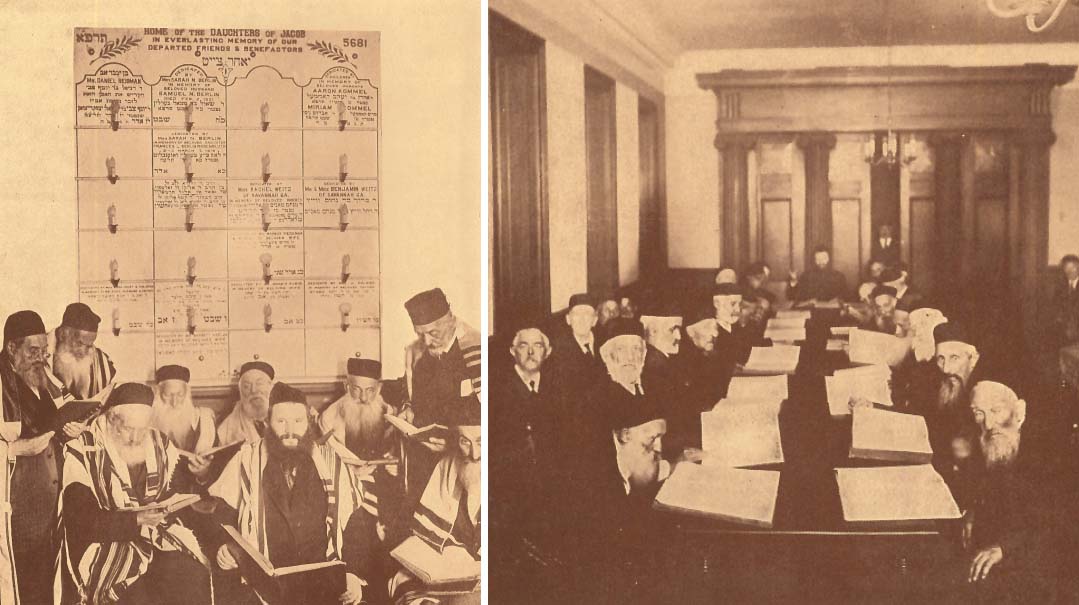

The Beis Medrash at Daughters of Jacob

Long before the advent of Social Security and Medicare, New York’s Jews proudly supported the efforts of the Home of the Daughters of Jacob on the Lower East Side. Founded in 1896, it was America’s first strictly kosher, shomer Shabbos nursing home. Originally housed at 40 Gouverneur Street, in 1904 it moved two blocks west to an imposing five-story granite and brick building located at 301 East Broadway. (It would later expand to include the two adjacent buildings.)

While immigrant German Jews had established their own senior care facilities as early as 1855, Eastern European Jews only began to arrive in America en masse toward the end of the 19th century. These immigrants tended to be young men who were eventually followed by their families. By the time the Great Immigration came to a halt in 1924, one-third of Russia’s Jewish population had departed that country. Yet the vast majority of the elderly population stayed put.

Those elder Jews who managed to immigrate to America faced several daunting challenges. The younger population struggled to make ends meet, finding jobs as rank-and-file laborers, positions that these eltere Yidden were no longer equipped to fill. To compound matters, many elderly Jews arrived in the United States and discovered to their chagrin that their children were no longer fully observant, and their grandchildren were completely ignorant of religious practice.

As one keen observer wrote at the time, “There was a closer tie between my grandmother, a distinguished laywoman in Kovno and Amsterdam, and a member of our family who lived in Jerusalem at the time of Hillel, than there is between my [American] son and his [European] grandfather. Two thousand years of capital, continuity, commitment, and relationship have dissipated in less than 80 years.”

To compound this issue, the majority of Jews who came to the goldeneh medineh found that the road to prosperity was strewn with obstacles; most struggled to stay above the poverty level. Famed Jewish communal worker Lee K. Frankel stated in 1900: “A condition of poverty is developing in the Jewish community of New York that is appalling in its immensity. If, besides the 50,000 people who applied to United Hebrew Charities, were we to include in the dependent classes all who needed the service of dispensaries, hospitals, asylums, and institutions of all kinds, or who were assisted by charitable effort other than that given by us, the statement can be safely made that from 75,000 to 100,000 members of the New York Jewish community are unable to supply themselves with the immediate necessities of life, and who for this reason are dependent in some form or other upon the public purse.”

Thus, the poor elderly Jews of New York were grateful to make Daughters of Jacob their home. The more than 300 “inmates” (as they were oddly termed at the time) were admitted as young as 70 and were welcome to live out the duration of their lives in one of the home’s two gender-separate dormitories. After a few years, when the home was expanded, married couples were afforded the privilege of private rooms.

A statement in a 1921 brochure conveyed the mission statement of Daughters of Jacob:

The Home carries out all that its name implies. It is not a place of refuge for the aged, but a Home, with the Sabbath lights glowing on Friday evening, the festivals of Purim, Hanukkah and Succoth observed, and the more sacred holidays kept reverently. There is the great Talmudic library for study, music to entertain, books to read, work to do to keep the mind and body active, a kind and cheerful word to everyone, tender care for the sick, and when the end comes, as it must to all, the aged patriarchs of our race are buried with that respect which the traditions of the Jewish faith impose.

The home was full of wise, adoring, colorful characters who were treasured by the local community. Schoolchildren would stop in on their way home to visit, and local rabbanim would be invited to deliver shiurim. The home’s beis medrash had a vast seforim library, and many of the men would spend their days there learning with their chavrusas. When Rav Meir Hildesheimer and Rav Aharon Walkin visited the United States in 1913 to promote the message of Agudas Yisrael, their hosts proudly swept them off on a guided tour of the “crown jewel” of the Lower East Side, where they were amazed to see a group of elderly men engaged in an intense Torah discussion in the home’s beis medrash.

Residents at the home consult with a nurse

Founding Mothers

The Home of the Daughters of Jacob (henceforth “Daughters of Jacob”) was founded by the downtown chapter of the Women’s Auxiliary of the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), led by the legendary Mrs. Bertha Dworsky. A devout Jew, she was a woman of dauntless strength and boundless energy who raised nine children — all while carrying the burden of the home.

Early on, before philanthropic families like the Fischels, Lamports, and Goldings came aboard as donors, she and the other women raised funds a nickel, dime, and quarter at a time. She spent early mornings at the docks greeting new arrivals to the country, and after putting her children to bed at night, she would traverse the city, raising funds for the home. Wherever she went, she carried along her famous big black bag. It contained raffle tickets, receipts, and dedication certificates, which she would have no qualms about hawking — wherever she might be.

One of her friends recalled: “Once, she came home late to dinner at eight o’clock, after being out all day in a snowstorm selling tickets for the annual gala. The black bag, almost empty of tickets, was now filled with bills. She had just sat down to dinner with her family and was on the brink of collapse when she happened to remember a friend five blocks away who had promised to buy two tickets. Out in the storm she went again and came back an hour later with the tickets sold. I know of hundreds of such incidents.”

When Mrs. Dworsky had the opportunity to travel to Palestine on the maiden journey of the ship President Arthur in 1925, much to her husband’s chagrin, the black bag went along. By the time they reached their first stop in Naples, more than $200 was wired home. When they arrived at their destination in Jaffa, the big black bag was filled to the brim with money once again. While the rest of the passengers were longingly embracing the holy ground, Mrs. Dworsky ran off looking for a bank so she could wire the funds home.

Among the renowned Jewish philanthropists who heeded the call were Macy’s department store owners Isidor Strauss and his brother Nathan. In 1912, Isidor and his wife Ida Strauss were returning from a trip to Europe on the Titanic. Despite Captain Edward Smith’s “women and children first” order, Isidor was offered a spot on a lifeboat. He refused and Ida turned down her space as well, allegedly declaring, “We have lived together for many years — where you go, I go.”

As beneficiaries of the Strausses’ philanthropy, Daughters of Jacob dedicated a memorial plaque in Ida’s memory at a November 1912 ceremony that was attended by the family and the city’s leading rabbis and dignitaries.

The capable women who shepherded the home were able to raise tens of thousands of dollars annually with a marketing budget of next to nothing —for they were assisted by the constant attention that the national media showered upon Daughters of Jacob and its storied residents. The New York Times published dozens of stories, among them a 1908 profile of Mrs. Rosie Aronwald, whose 107th birthday was attended by one of its reporters:

Mrs. Aronwald told a famous story of how she met Napoleon just a hundred years ago this spring, when she was only seven years old.

“It was after the Treaty of Tilsit,” she said, “and Napoleon was practically ruler of Warsaw, although the Duchy was nominally under the control of the House of Saxony. A Polish suspect, arrested for probable plotting against the government, had been condemned to be hanged. I went to him and begged that the man be not killed.

“He took me by the hand and said, ‘Why, little girl, do you ask me? Why come to me?’

“And I, who was just seven years old, said, ‘Because you are the head man here. You can have the man not hanged when you say so.’ ”

The story by this time had tired Mrs. Aronwald, so the old ladies, who, apparently, know the story as well as does the heroine herself, finished in a chorus: “Yes, so the man was not killed, because she saved his life.”

The elderly but energetic seniors at the “Bnos Yankev Meishev Zekeinim” (as the charges would call it) may not have spoken much English, nor could they move around like they once did, but they insisted on doing their part. Each year, the seniors hosted a bazaar at which they sold items they’d crafted themselves — knitworks, specialty foods, and artwork.

During World War I, when patriotic fervor swept the country, they made flags to sell at the bazaar, along with lemonade, because according to one of the home’s veteran residents, “There’s nothing quite as American as selling lemonade.”

In 1907, the oldest woman in America was a resident at the home; Sanz native Fannie Schlachet was born in 1794, a few months after the birth of the famed Divrei Chaim, Rav Chaim Halberstam, who was the town’s rav during her younger years. She was quite fond of saying in jest: “If only I had come to America a century earlier, George Washington and I would have gotten along well!”

Among the facility’s most celebrated personages was Suwalki native Esther Davis, who celebrated her (supposed) 117th birthday before passing away in 1911. A hardworking widow, she subsisted as a candle peddler long past her 100th birthday.

Each year the Daughters of Jacob hosted a gala Seder, with food prepared by the home’s chef in its state-of-the-art kitchen facilities. The event was heralded in a 1912 fundraising pamphlet: “No modern convenience has been omitted. The building has two complete kitchens: one for meat diet, another for milk diet. The equipment of these kitchens is an exact replica of the kitchens of the (luxurious) Hotel Pennsylvania.” Tradition had the home’s senior-most member address the participants at the start of the Seder.

On the last Pesach of her life, Esther Davis rose to speak and jovially remarked that she was feeling young. “Noach lived until the age of 950, so I’ve got plenty of time!”

Esther was also the founder and first president of the semi-official hierarchy at the home. Known as the Centenarian Club, it was open to residents who had reached age 100. In addition to the centenarians, the club also had one honorary member.

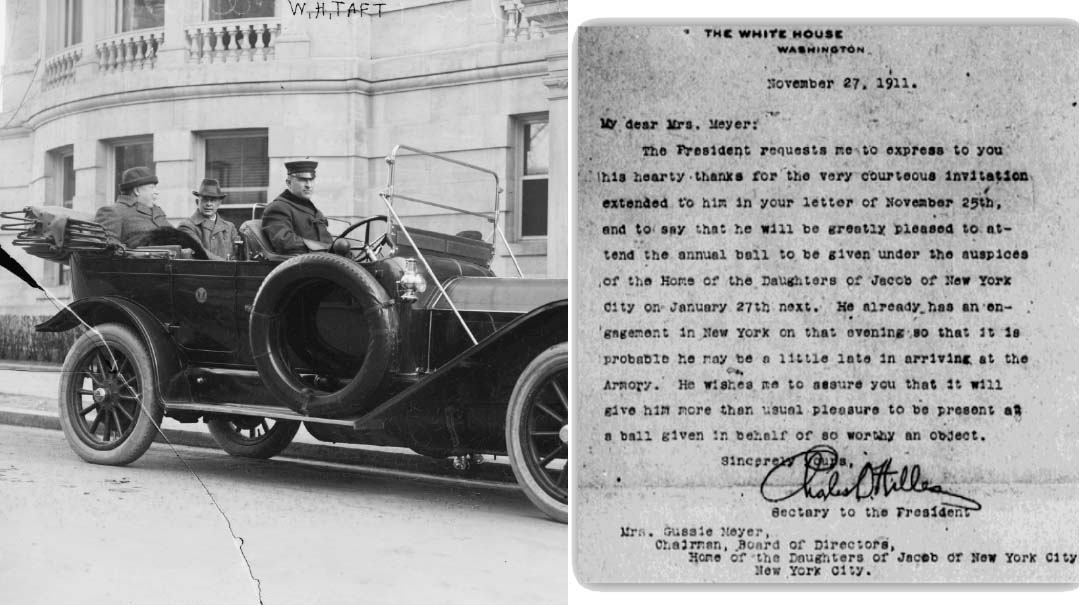

(Left) While his predecessor Teddy Roosevelt preferred horses in keeping with his Rough Rider image, President Taft became a fan of the motorcar when he discovered he could conceal himself from photographers with a “carefully timed burst of steam”

(Right) The front page of the Morgen Zshurnal was devoted to the acceptance letter from the White House

Hail to the Chief

In 1912, President William H. Taft accepted the invitation of Daughters of Jacob chairwoman Mrs. Gussie Meyer to serve as the guest speaker at the annual gala of the home.

When the news hit the street, pandemonium ensued. The next day, the sensationalist Morgen Zshurnal published the acceptance letter from the president on its front page (followed by a Yiddish translation, of course).

It marked the first occasion in American history that a president would attend an event hosted by an organization founded by “Downtown Jews.” For two months before (and several years after) the event was the talk of the town. Anyone who was anyone wanted to be in attendance.

Obviously, there were some skeptics who weren’t convinced that the president was coming, and opined that this was all just a massive PR stunt. For a short while, the skeptics had their way. While 5,000 merrymakers (the Yiddish newspapers reported 10,000) awaited on the night of January 27 at the mammoth 71st Regiment Armory on Park Avenue and 34th Street, President Taft and his entourage were nowhere to be seen. By 10 p.m., the organizers began to worry.

In fact, the president had arrived at Penn Station at 6:20 p.m. from Washington and was quickly whisked into his personal automobile. Taft was the first president to utilize a motorcar in an official capacity — the previous 26 commanders-in-chief had been transported by horse and carriage. The presidential “motorcade” (consisting of two cars) headed toward the West 48th Street home of the president’s brother Henry Taft — where he was to reside during his short stay in the city.

When the car hit 40th Street, it came to a sudden halt. The embarrassed chauffeur hopped out of the car and returned a short while later only to report that the “presidential limo” had run out of gas. The president took it all in stride and exited the vehicle to greet the large crowd that had stopped to witness this grand spectacle. After all, it was an election year. Eventually the president was provided with alternate means of transportation, and he was able to reach his destination.

At 11:25 p.m., the president and first lady arrived at the armory and were greeted with thunderous applause. The band began to play, and the president mounted the stage, waving to the adoring crowd like a king at his coronation. Following the extended ovation, the crowd was hushed, and the president began to speak:

“Among the many excellent qualities of the Jew,” said the president, “none commends itself more to admiration than his perfect system of charity. I mean the charity which he maintains to look after the poor and needy and the infirm. When you asked me to come to help you celebrate this ball of the Daughters of Jacob in the interest of the poor and the infirm, I seized the opportunity to do some good myself, and if I have brought any money for this purpose by being here, I shall feel that I have earned more for a good cause than I have ever earned before.”

The president went on to praise the patriotism of the Jews in the United States. He said that while he had “no criticism for the patriotism of the native born,” still he felt that “gratitude and appreciation of American institutions were more acute among those who came here later in life.”

Following the speech and presentation of gifts, the five senior-most members of the home were invited to meet him. This moment was memorialized by one of New York’s senior Yiddish correspondents, who witnessed the spectacle from up close:

Such an occurrence cannot be imagined in despotic Russia, in absolute monarchical Germany, in constitutional England, or even in Republican France…. It is true that kings or presidents honor Jews with their visits or by conferring distinctions upon members of their race, and President Taft has attended Jewish functions, but it has always been those of American Jews or those who by reason of the length of their residence in this country may be regarded, in every respect, as native Americans.

This was an occasion of Jewish immigrants most of whom have come here in the last two or three decades. This mass of people is recognized politically, but socially is considered of little consequence. Presidents and presidential candidates make their appearance in their midst in everyday garb and talk politics, but to come in evening dress to a social affair and accompanied as President Taft was by a lady of the family, is something to which the immigrant is not accustomed.

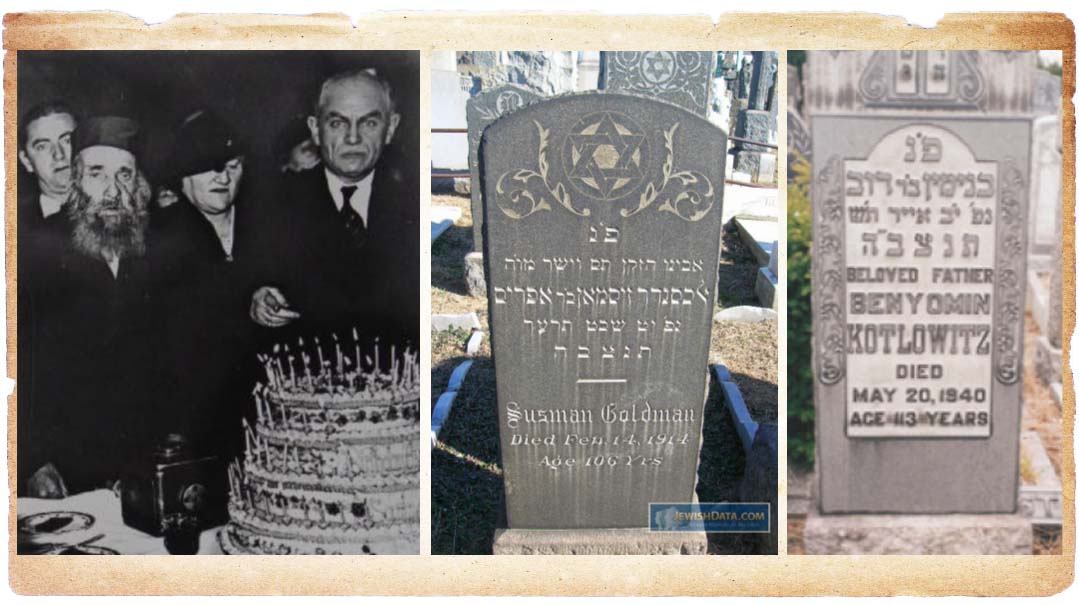

(Left) Samuel Baron (left) receives a birthday cake adorned with 106 candles from the president of the home, Max Weinstein

(Middle) Susman Goldman was one of the legendary centenarians at the home

(Right) While Benjamin Kotlowitz claimed to be 113, official documents showed he was 98. The same probably held true for many members of the home, who lost track of their birthdates over time

Led by 102-year-old Nissen Rosenstein, the quintet informed the president that he had been granted admission into America’s most exclusive club, the Home of the Daughters of Jacob Centenarian Club. They then offered their blessing to the amused president, wishing him a long life (which was fulfilled) and a victory in his upcoming election (which he lost).

Even in defeat, Taft would have been proud to know that he had the vote of one of the home’s most beloved part-time residents:

Simon Harris, 104 years old, whose legal residence is in New York, but who lives in Jerusalem —except when Presidential voting time comes in the United States —was one of the home’s prime movers. Mr. Harris came to this country more than a half century ago, but after casting a vote for Abraham Lincoln, returned to Jerusalem to die, as he thought. He did not die, however, and comes over every four years to vote the Republican ticket, being registered in the Fourth Assembly district.

When World War I began during the summer of 1914, many of the residents at the home worried deeply for their relatives back in Europe. A meeting was held at the home and it was decided that a group of the home’s elders would begin to recite Sefer Tehillim throughout the day until hostilities ceased. When the New York Tribune reported on this in 1916 under the headline “Seven Men’s Faith Defies 12 Kings,” the story gained legs and was carried by thousands of newspapers around the world.

All day long the seven wise men pray unceasingly for peace. Their white beards, beards such as the old prophets of Israel might have worn, stream down to the narrow table about which they sit. The electric lights of the Home of the Daughters of Jacob, 301 East Broadway, shine upon black skullcaps, upon faces where the scars of suffering are being softened by the gentle dignity that comes to the very old. Every minute of the day, from 6 in the morning until 9 at night, the prayers of the seven wise men rise to G-d… that the strife in Europe may end. So they have prayed since the war began. So they will pray until the nations, or they themselves, enter into peace. Surely G-d will hear in time the pleadings of these very old men who trust in Him.

Another favorite at the ageless facility was 101-year-old, Vilna-reared Michla Shilotzky, who claimed to anyone who would listen that she possessed a “magic necklace.” Philadelphia’s Jewish Exponent reported:

Mrs. Shilotzky, unlike other faith curists, does not insist that her necklace is all-powerful, but simply claims for it a mysterious power. “I don’t think that in any big illnesses it does any good,” she said. “For instance, once I fell down the stairs, and I know my necklace did nothing to stop the pain, but in smaller ailments, such as an earache or toothache, it does seem to perform wonderful cures, and many persons come to me from all parts of the country, only just to touch the necklace, and they assure me that this affords them relief.

“I got the necklace eighty years ago, and I have worn it regularly ever since,” Mrs. Shilotzky furthermore said. “It came into my possession from another branch of the family, but it had been handed down from generation to generation for more than two hundred years. It did not spare my husband, however, and failed to be of any benefit to my poor boy when he was taken ill; still, I never lost faith in it, and after all, faith is the great thing. In my own case it has cured many little illnesses, but the cures it has performed for other persons are really wonderful, if I can believe what they tell me.

“Hardly a day goes by that I do not have a caller. Some mothers bring their children and ask me only just to touch them with my necklace, and they go away perfectly happy, and some of them come back days after and tell me the little ones are quite well. Of course, I am only too glad to please them, but occasionally so many come that I get quite tired, and they bother me. In fact, one day a woman persisted in pestering me with questions, asking where I got the necklace, who gave it to me and who I had cured. Finally, she asked me where I was from, and so to get rid of her I said I was found in a field in Russia, and this made her so angry that she went away and never bothered me again.”

Mrs. Shilotzky’s magic may have impressed some, but when 81-year-old Henry Cohen arrived at the home in 1925, he quickly became the center of attention: “He’s the greatest fun-maker of all the jolly ‘young men.’ For twenty years he was an acrobatic clown with Barnum and Bailey’s Circus. He’s a juggler and a dancer, and can sing and do the buck and wing.”

In 1938, Benjamin Kotlowitz celebrated his 113th birthday at Daughters of Jacob, an event that was covered (and embellished) by the international media. After congratulatory letters from President Roosevelt and Governor Lehman were read, Kotlowitz went on to repeat the same pshetl he had said a century earlier at his bar mitzvah in his native Russia. (A cursory glance at Mr. Kotlowitz’s profile on Ancestry.com shows that, according to official documents, he was 98 at the time, but hey, what’s 15 years when you’re having fun?)

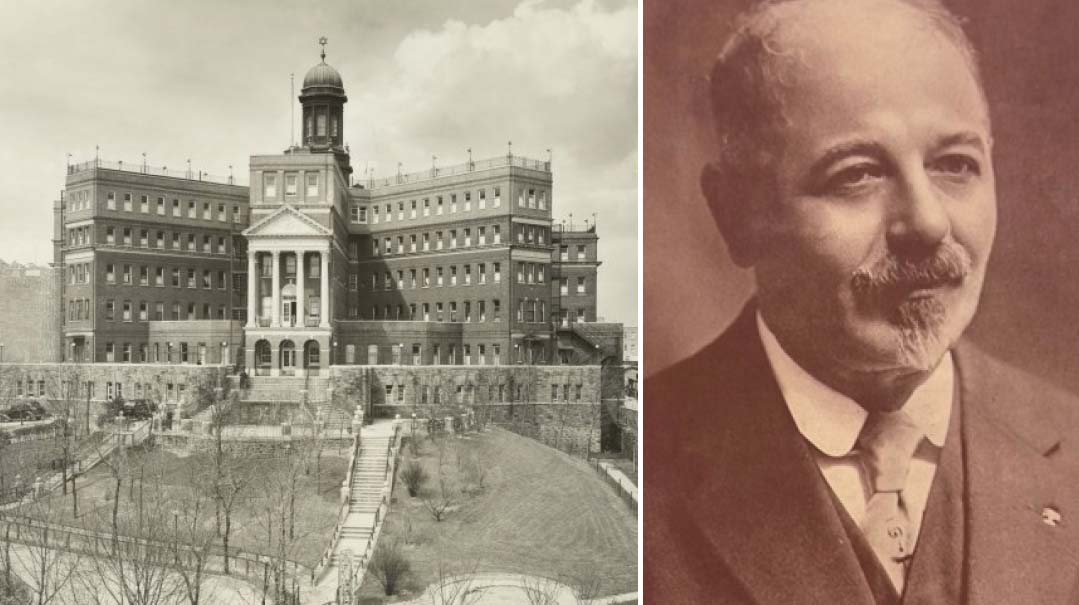

In 1920, the Home of the Daughters of Jacob moved uptown to its new, world-class campus in the Bronx, which was dubbed by the media “a palace for old Jews”

(Right) Albert Kruger, Volozhin talmid and esteemed Jewish communal activist, was Daughters of Jacob’s longtime superintendent

Moving On Up

The longtime superintendent at the home was Mr. Albert Kruger. Born into a Minsk rabbinic family in 1866, he studied in the Volozhin yeshivah from 1883 through 1889. In addition to his vast Torah knowledge, he possessed world-class management and public relations skills, and gentlemanly manners to boot. He threw himself into his work with boundless energy and enthusiasm and acted with broad vision. During the course of his 25-year tenure, he served as the face of the institution — if not the titular face of Eastern European Jewry in New York at the time. When asked what the home’s mission was, he would say, plainly and simply, “To keep old men young.”

When elections for a governing board were held for the New York “Kehillah” in 1911, Albert Kruger was chosen alongside venerable rabbis and titans of industry. When a fire broke out in the home in 1908, he was photographed swiftly carrying out an immobile resident and then rushing back into the smoke-filled building to rescue another.

One of Kruger’s most trying annual tasks was in the days prior to Yom Kippur, when he would convene a team of doctors and leading rabbis to determine who could or could not fast on Yom Kippur. The respect that Kruger garnered from the residents was enough that they followed the decision of his venerable council. However, in the year following his passing, things didn’t quite work out the same way:

Refusing to take advantage of the immunity which age would give them, three inmates of the Home of the Daughters of Jacob, whose ages total 299 years, announced yesterday that they would carry out the orthodox tradition of their faith and fast during Yom Kippur. Miss Stella Glassner, an official of the home, addressed the 500 old folk in the synagogue of the institution in the afternoon. She pointed out that age gave immunity from fasting from sunset Friday to sunset Saturday and she asked how many of those present wished to be absolved from the fast.

“Mother” Rachel Beile Kriegel, who is 91 years old and has been blind for twenty years, rose and said: “I have kept the fast ever since the days when in Russia I was young. If I am old, what difference? I will fast as I hope the others here will.”

She sat down and Chaim Rothstein, who is 105 years old, got to his feet. “I too will keep the fast,” he said. Mr. Rothstein is still active and does not use eyeglasses. The other of the three oldest inmates who declared she would fast was Chaye Sentz. She is 103 years old. After that no one signified that he or she would claim immunity from fast.

Albert Kruger’s crowning achievement, however, was a project that took him more than a decade to complete. At a special meeting of the home’s board of directors in 1911, a motion was raised to double the size of the home, so they could meet the demand that had grown as a result of increased immigration. A short time later, 36 lots were purchased uptown in the Bronx, at 167th Street, Findlay, and Teller Avenues for the purpose of building a new state-of the-art home. At the 1912 gala that President Taft attended, Kruger announced plans to the masses, and a subsequent appeal netted more than $60,000, with the president counted among the donors.

Still, there was much work to be done. The building committee, led by esteemed philanthropists Elias Surut and Harry Fischel, and later joined by Isaac Phillips, Max Weinstein, and Judge Otto Roswalsky — led the charge to build what Kruger deemed “the largest moshav zekeinim in the world.”

By 1916, the plans were filed, permits received, and in a star-studded ceremony, a golden shovel was planted into the ground by Harry Fischel. But the arrival of World War I put a damper on the grandiose plans. Raising nearly $2 million (the equivalent of more than $40 million today) was an impossible task at a time when all resources were being directed toward war and relief efforts. With a large portion of the frame already completed, construction was halted in 1918.

Even though many of its members were active in the Joint and other Jewish relief efforts, the building committee was not ready to give up. They redoubled their efforts, initiating then-novel fundraising ideas like selling bricks, beds, rooms, and wings. Celebrated actor Eddie Cantor dedicated a bed in memory of his elderly grandmother. Schoolchildren went door to door selling lines and pages in the Daughters of Jacob Golden Album, and more than 9,000 donors joined the campaign. Promiment Uptown philanthropist Jacob Schiff and his son-in-law Felix Warburg made significant bequests, and leading corporations were signed up as sponsors. Once complete, it marked the most lucrative building campaign for an Orthodox institution in New York to date.

On May 10, 1920 — with the assistance of the Red Cross — a motorcade led by 22 ambulances transported the residents to the sparkling new campus. Recently discovered video footage shows sifrei Torah being carried onto East Broadway as thousands awaited outside to sing and rejoice along over this monumental accomplishment.

The much heralded departures of the Home of the Daughters of Jacob (1920) and later Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchok Elchonon (1928) from 301-303 East Broadway to vast campuses uptown were both celebrated as momentous occasions for Orthodoxy in America

The following month, Daughters of Jacob officially inaugurated its new home —dubbed by the New York media “a palace for Old Jews” —with a weeklong celebration and the admission of hundreds of new residents, many of whom had been languishing in subpar municipal shelters, dreaming of entry to the coveted home. With the addition of an on-site hospital wing, the new facility was able to accommodate those with more severe conditions. The shul at the Bronx home was built to seat more than 1,000, allowing residents to host family celebrations without ever leaving the confines of the home.

One month following the move uptown, the iconic building on East Broadway was sold. The buyer was a familiar one to the Daughters of Jacob board of directors — for it was the country’s premier Torah institution, Yeshivas Rabbeinu Yitzchok Elchonon — where several of them served as lay leaders.

The sweet sounds of Torah that once emanated from the beis medrash at Daughters of Jacob would persevere, carried on by America’s first generation of Torah scholars. In place of centenarians Nissen Rosenstein, Alter Silverman, and Mendel Diamond, the benches would be occupied by budding scholars, among them the future rabbanim and communal leaders Joseph Kaminetsky, Chaim Pinchas Scheinberg, Avigdor Miller, Isaac Tendler, Menachem Perr, Yechiel Michel Charlop, and Nosson Wachtfogel. Its walls would continue to reverberate to the familiar words of Abaye and Rava as the young charges thirstily drank from the shiurim of Rav Moshe Aharon Poleyeff, the Meitsheter Illui, and Rav Shimon Shkop. For the “hosts of Torah,” it was a truly befitting reward. —

Note: The comprehensive works and knowledge of the following esteemed individuals and publications were utilized in the preparation of this article: Chaya Sara Herman, Yehuda Geberer, Ariel Segal, Rabbi Dr. Aharon Rakeffet, Dr. Shaul Stampfer, Dr. Edna S. Friedberg, Rabbi Gavriel Schuster, Rabbi Herbert Goldstein z”l, Harry Fischel z”l, and Dr. N. Sue Weiler a”h.

The Moshav Zekeinim in Yerushalayim

Elder Care in the Old World

Part I: Palestine

“Old men and women shall yet sit in the streets of Jerusalem…”

The Old Yishuv in Ottoman Palestine established an institution for the community’s elderly in 1878 in the Old City. Male members of the Ashkenazi community were able to receive a cup of tea and a hot meal, and enjoy the social atmosphere among other elderly. By 1893, a women’s division had opened its doors, and in that same year it expanded operations into a full-fledged old age home.

Having outgrown its crowded quarters by the turn of the century, it acquired an isolated outpost at the end of Rechov Yaffo where the elderly “settlers” held the city’s western flank. They were soon joined by Jerusalem’s first psychiatric hospital, Ezras Nashim, across the street, and not long after by Shaare Zedek’s modern hospital facility down the block.

Not to be outdone, the Sephardic community of the Holy City constructed an old age home for their elderly in 1906. The famed Turkish Jewish banker Chaim Aharon Valero funded most of the acquisition of the property, which happened to be right across the street from Shaare Zedek. For the ensuing decades, these four health care institutions greeted arrivals at the entrance of the city.

Another noteworthy moshav zekeinim was the Bar Yochai Yeshivah and Dwelling for the Aged. Founded in 1898 in Meron, it was located directly above the tziun of Rabi Shimon bar Yochai. The residents would sit and learn in tranquility at this holy site. Interestingly, the supporters of this initiative were many of the same people who funded the Daughters of Jacob home.

The old age home in Brisk held a special place in the heart of Rav Chaim Soloveitchik

Part II: Europe

On his historic 1846 visit to meet Czar Nicholas I in St. Petersburg, the great Jewish shtadlan Moses Montefiore spent a day in Warsaw. He was accorded royal treatment and given a tour of the city’s Jewish sights, among them Matthias Rosen’s Aged Needy Asylum, which Montefiore praised effusively in his diary.

Interestingly, the Warsaw home was intended to provide housing for both orphans and the aged. In the first two decades of its existence, 1,913 orphans and 1,135 elderly found shelter in the institution. Its bylaws provided for a minimum age of 60 to qualify for admission, and for at least three years of previous residence in Warsaw. The second home to open in Eastern Europe was in Vilna, which opened its first moshav zekeinim in 1864.

During his tenure as rav of Kovno, Rav Yitzchok Elchonon Spektor was involved in opening a kosher old-age home in the city, and no less than Rav Chaim Soloveitchik was the patron of the old age home in Brisk, which he included among his most essential causes.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 888)

Note: The comprehensive works and knowledge of the following esteemed individuals and publications were utilized in the preparation of this article: Chaya Sara herman, Yehuda Geberer, Ariel Segal, Rabbi Dr. Aharon Rakeffet, Dr. Shaul Stampfer, Dr. Edna S. Friedberg, Rabbi Gavriel Schuster, Rabbi Herbert Goldstein z”l, Harry Fischel z”l, and Dr. N. Sue Weiler a”h.

Oops! We could not locate your form.