When the Founding Fathers Spoke Yiddish

| June 3, 2025For just 25 cents a Jewish immigrant could purchase America’s founding documents rendered into the familiar rhythms of mamme loshen

Title: When the Founding Fathers Spoke Yiddish

Location: New York

Document: The US Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, in Yiddish

Time: 1892

“US Constitution and Declaration of Independence in Yiddish” is one of the featured chapters in the forthcoming 100 Objects from the Collections of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research — a sweeping journey through Jewish life, memory, and survival, told through a carefully curated selection of artifacts. This beautifully illustrated coffee-table volume showcases rare manuscripts, photographs, and ephemera, each accompanied by insightful essays from leading scholars that bring these treasures vividly to life. The limited-edition book can be purchased via the YIVO website.

The year 1892 held particular significance for American Jewry. It marked not only the centennial of the Bill of Rights, but also the peak year of Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe — nearly 120,000 souls would arrive that year alone, part of a massive wave that would bring over two million Jews to American shores between 1880 and 1924.

Among the throngs stepping off steamships at Castle Garden that year were thousands who had never known political participation. They came from czarist Russia, Galicia, and Romania — places where the very concept of citizenship was as foreign as the English language itself. Yet America demanded something unprecedented of these newcomers: not just loyalty, but an understanding of democratic principles that had been denied to them for centuries.

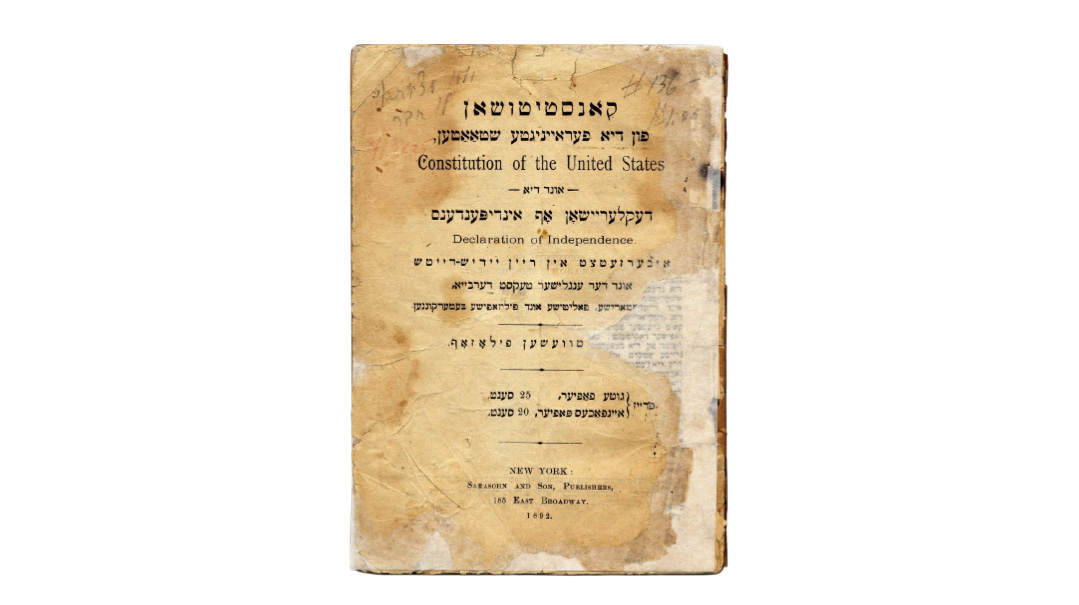

It was against this backdrop that a remarkable 132-page booklet appeared at 185 East Broadway, published by the pioneering house of Sarasohn and Son. For just 25 cents — the price of a decent meal — a Jewish immigrant could purchase America’s founding documents rendered into the familiar rhythms of mamme loshen. The author was Getsl Zelikovitsh (1863–1926), a colorful, Lithuanian-born intellectual who styled himself as “Der Litvisher Filozof” — The Lithuanian Philosopher.

But this was no mere academic exercise. Until 1906, there was no standardized citizenship test in America. Each federal judge determined for himself what it meant for an applicant to demonstrate “attachment to the principles of the Constitution,” as required by the 1802 Naturalization Act. Some judges were lenient; others conducted rigorous examinations. For a Yiddish-speaking tailor facing a stern magistrate, Zelikovitsh’s booklet could mean the difference between citizenship and rejection.

Zelikovitsh understood this predicament intimately. His translation wasn’t a literal word-for-word rendering, but rather what he called a “historical, political, and philosophic” interpretation. The opening lines of the Declaration — “When in the course of human events” became “Ven es kumt in di menshliche geshichte az a folk zol zich oislozen fun di politishe bandn....” The rhythm was distinctly Jewish, the sentiment unmistakably American.

The booklet’s cover tells its own story. The Hebrew script appears first — “Konstitooshon fun di Fareingigte Shtaaten” and “Deklaratsyon af Independenz” — followed by English translations. This wasn’t mere decoration but a declaration: The immigrant need not choose between old world and new. He could carry both in his pocket.

Perhaps most tellingly, Zelikovitsh included a practical appendix listing every US state with its distance from New York City. To a community concentrated in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, this transformed America from an abstract concept into something tangible and navigable.

Today, surviving copies of this booklet are treasured artifacts, housed in archives and private collections. They remind us of a pivotal moment when Jewish immigrants, armed with nothing but determination and a 25-cent pamphlet, transformed themselves from subjects of distant and cruel empires into citizens of the land of the free. The Pious Publisher

Behind the publishing of this remarkable pamphlet stood a devout Jew, Kasriel Sarasohn (1835–1905), whose very life proved that one could be both a faithful Jew and an exemplary American citizen. Having arrived in New York in 1871, Sarasohn founded America’s first Yiddish daily newspaper, Yidishes Tageblatt, in 1885, while maintaining strict observance and supporting traditional Jewish causes worldwide.

His decision to publish the Constitution in Yiddish wasn’t merely business — it was a manifesto. At a time when many believed religious observance and American integration were incompatible, Sarasohn demonstrated the opposite, through deed and word. He supported the poor in the Old Yishuv, aided fresh immigrants, and founded an organization that merged with HIAS in 1890 — all while championing American democratic ideals in Yiddish.

From Sarasohn and Son headquarters at 185 East Broadway, he offered living proof that devotion to Torah and loyalty to America could not only coexist, they could strengthen each other.

Yiddish Meets Arabic

Zelikovitsh’s dedication to helping fellow Jews didn’t end with American citizenship. In 1918, recognizing the practical needs of Jewish pioneers settling in Eretz Yisrael, he published Arabish-Idisher Lehrer (“Arabic-Yiddish Teacher”), a 32-page guide teaching colloquial Arabic to Yiddish speakers. The book begins with the author’s name and a short biographical note: “Prof. G. Zelikovitsh, former chief dragoman for Arabic with Field Marshal Lord Kitchener in Egypt.”

Initially serialized in the Yidishes Tageblatt, this groundbreaking textbook was likely the first of its kind, designed specifically for Jewish immigrants who needed to communicate with their Arab neighbors. Zelikovitsh’s approach was both practical and culturally sensitive — he used familiar Yiddish letters to help readers pronounce Arabic words, and remarkably, he suggested that students learn together using the traditional yeshivah chavrusa method. While well-meaning, the book likely gained more attention for its unusual premise than its actual utility.

Next week’s column will expound upon the fascinating life (and legend) of Getsl Zelikovitsh, including his adventures as a translator and journalist embedded with British expeditionary forces in Africa during the 1880s.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1064)

Oops! We could not locate your form.