When Rebbi Was Young

Ten years after Rabbi Shmuel Kunda's passing, his magic lives on

Photos: Family archives

Over the years, Rabbi Shmuel Kunda’s brilliance, humor, and unparalleled storytelling skills brightened the lives of a generation of children, but it all started out within the four walls of his classroom. One of those early-day talmidim was Mordy Mehlman, today a grandfather, publisher of the Flatbush Jewish Journal and president of Citicom marketing company. Although he was only a kid then, he forever views Rabbi Kunda as his rebbi, happy to share the memories that have continued to make him laugh and keep him inspired ten years after Rabbi Kunda’s passing

Which child doesn’t feel like best friends with Chananya Yom Tov Lipa Katznelenbogentstein?

The protagonist in The Magic Yarmulke, Shmuel Kunda depicts young Chananya as a hapless young boy for whom little seems to go his way. One day, he sits down at the side of the road, bemoaning his very unfortunate lot in life. He’s then approached by a strange-looking fellow named Yankel the Yarmulke Man, who gives him a multi-colored yarmulke which will supposedly do wonders. Chananya places the yarmulke gingerly upon his head and, the next thing you know, his life takes a wild turn for the better. He begins to accomplish amazing things, including the Olympian feat of punching the ball out of the park — over the head of Simcha Shtark! That’s until one day when a gust of wind blows the yarmulke right off of poor Chananya Yom Tov Lipa’s head and he’s engulfed in a wave of despair.

Suddenly, old Yankel reappears. A conversation ensues in which Yankel reveals that the magical yarmulke was actually not magical at all. “Ayaya, no, no, the magic won’t stop... You see, that yarmulke that made you feel ten feet tall, really had no magic in it at all.” Chananya begins to catch on. It was never the yarmulke — that was just Yankel’s way of forcing the young boy to believe in himself. Realizing this, Chananya is ecstatic. “That means I can still be as good as I want to be!… Oh, is that ever great news, Yippee!

And then he concludes, “The magic is not in a kippah, it’s in me, Chananya Yom Tov Lipa!”

It was a magic he never knew existed until Yankel the Yarmulke Man made him believe in it — and that Shmuel Kunda wanted every Jewish child to believe.

Mordy Mehlman was just 12 years old when he first came in contact with that magical spark. Today, Mordy is a proud father, grandfather, publisher, and community leader. Yet even after all these years, a large part of the inspiration he lives with is that of his first and foremost rebbi, Rabbi Shmuel Kunda a”h, who passed away on Rosh Chodesh Cheshvan 2012.

For Mordy, it all began on his first day of seventh grade at Yeshiva Torah Vodaath of Flatbush. Mordy hadn’t forgotten to bring a nickel for that morning’s bus fare, but he was feeling queasy nonetheless. First days of school were always hard, fraught with doubts, concerns, and fears of the unknown. The rebbi he was assigned to this year was a brand new one — a fellow by the name of Kunda — and the fact that Mordy had never heard of him before made his sense of foreboding all the more dominant. Then the door opened with a sudden swish of energy.

“From the moment he walked in,” says Mordy, “we knew that he was radically different from anyone we had ever met before. He was so positive, he was fun, exciting, warm, caring, and much, much more.” Such was Mordy Mehlman’s introduction to the legend that was Shmuel Kunda, the rebbi who would effuse a boundless love for life and instill the confidence to hit every ball over the head of the proverbial Simcha Shtark.

Don’t think of your troubles and they’ll never ever find you

Run ahead of everyone and never look behind you

And never look behind you

You’ll only win and never fail just let the wind go through your sail

And see your spirit fly (The Royal Rescue)

Seventh grade changed Mordy Mehlman’s life (he’s in the blue shirt and tie, standing next to Rabbi Kunda). A rebbi for life

Spreading the Joy

Rabbi Shmuel Kunda was born on the 18th Tishrei in 1946 and even that came with the sort of adventurous twist that would make for a perfect children’s tape. His father, Reb Zalman Kunda, was an alter Mirrer and was part of the Mirrer Yeshiva’s storied escape from Europe and its years-long hiatus in Shanghai. The Podrabiniks were a family that had also escaped along with the Mir, and Zalman Kunda was introduced to their daughter Ita. Zalman and Ita were married in Shanghai and, about a year later, celebrated the birth of a baby boy whom they named Shmuel. Along with the rest of the Mir, the family was granted entry into the United States, and, in 1947, set sail for New York where they were greeted by the symbolic triumph and valiant promise of the Statue of Liberty.

Our grandparents came to this land,

A land they did not understand.

They made their new start

With hope in their heart,

And all that they owned in their hand… (When Zaidy Was Young 2)

For elementary school, Shmuel attended Rabbi Jacob Joseph School (RJJ) on the Lower East Side. He then became a talmid of the Mirrer Yeshiva in Flatbush and shared a close relationship with the roshei yeshivah, Rav Shraga Moshe Kalmanowitz and Rav Shmuel Berenbaum, as well as the mashgiach, Rav Hirsh Feldman, zichronam livracha. These great rebbeim, serious as they were, held a special place in their heart for the Kunda boy, who brought so much simchah to all those around him.

In yeshivah, Shmuel wasn’t just a good friend — there was something about him that uplifted any atmosphere he was part of, be it the contagious good cheer or the constant witticisms that just seemed to roll off his tongue.

But funny as he was, there was also a serious side to him. As a talmid of the Mir, Shmuel was privileged to be part of the yeshivah’s legendary ahavas haTorah, and that part never left.

Even decades later, frequent mispallelim at the “Lakewood Minyan” in Boro Park, where Shmuel Kunda lived for many years, would tell of how Shmuel would daven Maariv, open a Gemara, and not look up until midnight.

Perhaps it was that love for learning that propelled him to what became his initial foray into the world of children’s entertainment. Shmuel grew up during the immediate postwar era, when a generation of exhausted European parents were trying their best to raise children in a culture that appeared to offer limitless, albeit unholy, freedom and opportunity. He watched as a generation of energetic children began to resign on the hope for the inspiration their neshamos craved; the world outside was beckoning, and the tempting alternatives would only grow increasingly irresistible.

It was at that moment that the fire inside of Shmuel Kunda began to blaze outward. Pirchei of 14th Avenue was a popular destination for Jewish children at the time, and Shmuel took on the role of Pirchei leader. Storytelling was part of that role, and it soon became apparent that here was a talent of unparalleled proportions. Kids from homes that stood vulnerable to the new reality, who grew up on stories of a very different sort, began to flock to the Shabbos afternoon Pirchei group where their leader held them spellbound with tales that flowed with messages of hope and positivity. Members of different Pirchei groups would break protocol and head over to 14th Avenue where they too could watch the new storytelling sensation in action. Children who had previously only been exposed to their fathers’ shtiblach, whose membership consisted solely of Holocaust survivors, were now transitioning over to the Pirchei minyan. There, they’d daven for the amud, receive aliyos, and lift the Torah high and proud when given hagba’ah.

At 22, Shmuel married Naomi Cohen of Detroit, Michigan. Over his decades-long career, admirers of the larger-than-life personality of Shmuel Kunda would have a hard time guessing that his reserved, mild-mannered, and well-organized wife was actually a very active partner in his work, often using her razor-sharp intuition to call the shots in the development and production of her husband’s numerous children’s tapes.

Following their marriage, Shmuel joined the Mirrer Yeshiva’s kollel. But it wasn’t long afterward that he was approached by his rosh yeshivah, Rav Shraga Moshe Kalmanowitz, who had an interesting proposal. A fairly new elementary school called Yeshiva Tiferes Tzvi needed a fifth-grade rebbi: Would Shmuel Kunda want the job?

Shmuel accepted, his boisterous character and love for spreading joy to Jewish children making it obvious that this was a position he was most suitable for. He turned out to be a mechanech with uncanny intuition; he understood immediately that certain novel concepts would need to be introduced to capture the hearts of the new generation. He brought the book The Family Y Aguilar by Marcus Lehman to school, and, if the boys learned well, he’d award them with a 15-minute reading, replete, of course, with voices that ranged from terrifying to dramatic to absolutely hilarious. He specifically chose the book, which describes a family who secretly observed Judaism during the Spanish Inquisition, for its message of heroic sacrifice in the face of overwhelming opposition. This was precisely the message he wanted his talmidim to internalize.

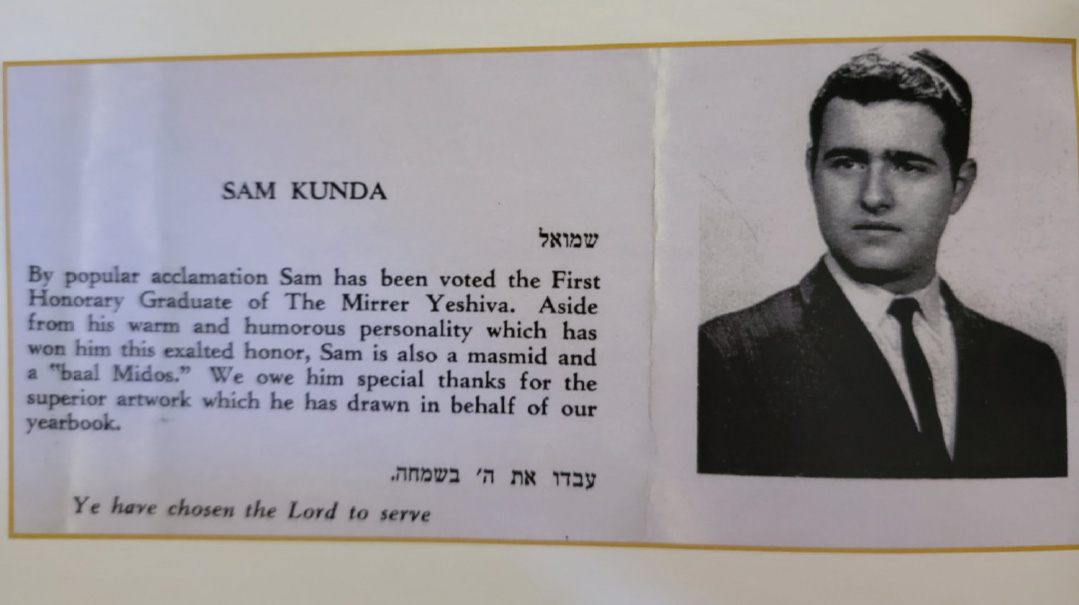

Funny and a masmid, accolades from the Mirrer yearbook

He Lifted Us

Shmuel’s reputation as a star mechanech grew, and he was soon hired by Torah Vodaath in Flatbush to serve as its seventh grade rebbi. The class list included one Mordechai Mehlman.

Now Mordy sat there, the butterflies in his stomach somehow completely evaporated as he watched this unusual rebbi teaching something but expressing so much more as he stood before a class of seventh graders who had never paid such riveted attention to anyone. Heshy Himmelstein may not have been born yet, and Anshei Kartufel’s steamless radiator still not yet installed, but it was all there, bubbling inside of him, the kaleidoscope of talent bursting forth with an unstoppable exuberance for all things Yiddishkeit.

In the classroom, all of that spilled over, and Mordy and his classmates felt it immediately. “Every minute of the entire year was filled with enjoyable learning, inspiration, excitement, and stories,” Mordy reminisces. “He was also an incredible artist and drew everything we learned on the board. Within minutes, the sho’eil, the mash’il, the parah — all became alive.”

Students from his early years in Tiferes Tzvi have similar recollections, with an added tidbit. Shortly before Shmuel Kunda’s joining the staff, a large school had recently shut down and given away all its blackboards. Yeshiva Tiferes Tzvi took them — why not? — and their classroom had blackboards covering three out of four walls. All across the classroom were pictures of angry bulls ready to pounce and farmers chewing on a straw of hay.

Seventh graders aren’t known for their passionate love for academia, but that year saw something different. “I actually looked forward to going to yeshivah,” Mordy remembers. “Rabbi Kunda made us feel so good about ourselves — positivity was his whole essence. He lifted us all up. He made us love school.”

Rattlin’ and shakin’

What a ride we’re takin’

It doesn’t matter

If you’re going near or far

Even with a fever

I’ll go to yeshivah

If I can just ride

On my trolley car. (When Zaidy was Young 1)

Mordy may have been willing to hop on the trolley to yeshivah even with a fever but, unfortunately, it was something a bit more severe than that which made him unable to complete the school year. “I got mono during the last two weeks of school. It was very hard for me — I wanted so badly to get in the last few days with Rabbi Kunda.”

One evening, Rabbi Kunda showed up at his house with one of his original paintings of the Kosel, which he autographed for his young talmid.

“Rabbi Kunda had thousands of paintings,” Mordy tells me. “All his paintings depicted some aspect of Jewish life, be it the Kosel, or a scene of a grandfather learning with his grandson. His paintings were magnificent.”

Rabbi Kunda was also completely ambidextrous and, when one hand tired from drawing, he simply switched to the other. He drew the pictures featured on all the front covers of his albums as well as the illustrations for the several Shmuel Kunda books that he published. His drawings were created with head-spinning rapidity, and as his fame spread, many children would approach him, nervous and starstruck, and, rather than an autograph, he’d give them an original drawing on whatever surface might be available. From canvases to the backs of wedding invitations, Shmuel Kunda’s drawings tell a story of their own: Yiddishkeit is an art whose beauty can forever be discovered. Each uncovered layer reveals another burst of color, another vista into the infinite world of Torah.

Mordy completed his seventh-grade year with a newfound joy for learning. At the year’s end, rebbi and talmid said goodbye to each other, but it was a premature farewell.

The following year, when Mordy was in eighth grade, he was selected as an integral brushstroke in Shmuel Kunda’s next project.

“Rabbi Kunda came down to our house to have a meeting with my parents and me. We sat around our kitchen table and he announced that he planned on opening a camp for the upcoming summer. He then said that he would like for me to be the first applicant.”

It’s a scene that sounds like something straight out of the Lower East Side but it gets better. Although Mordy’s parents were hesitant, they knew how talented Rabbi Kunda was and trusted his ability to open a successful camp. They tentatively agreed to send Mordy to the not-yet-existing camp and a grateful Rabbi Kunda asked for a deposit. Mr. Mehlman senior reached for his checkbook.

“All right,” he said, “what’s the name of the camp?”

Rabbi Kunda stared at him blankly.

“Name? It doesn’t have a name yet.”

With that, Mordy Mehlman was registered to a nameless camp, he and his parents trusting implicitly that the magic of his beloved rebbi would somehow make this work.

“Actually,” says Mordy, “the camp remained without a name for a while. Rabbi Kunda called the Jewish Press to place an ad in the paper for his new camp. They too asked for a name. Once again Rabbi Kunda responded that there wasn’t any yet. The paper told him adamantly that they couldn’t advertise a camp without a name and that if he didn’t provide one shortly, the ad wouldn’t go in. And so, on the spot, Rabbi Kunda decided. “Naarim,” he said. ‘The name is Camp Naarim.’ ”

Camp Naarim began that year — 1973 — with the young Rabbi Shmuel Kunda and Rabbi Dovid Presser at the helm. For many years, a dynamic trio helped lead the team: Rabbi Yaakov Bender served as head counselor, Rabbi Yossi Friedland as assistant head counselor, and Rabbi Zevi Trenk as the learning director. It was quite the dream team, and for Mordy, along with his fellow campers, it made for most memorable summers. “I thrived in Camp Naarim,” says Mordy. “I remained a part of the camp for 25 years.”

Shmuel Kunda’s selection of Rabbi Yaakov Bender as head counselor wasn’t random — their relationship dated back many years. Rabbi Bender retold the story at Shmuel Kunda’s levayah.

“I had arrived as a young new talmid in the Mirrer Yeshiva, brokenhearted over the recent and sudden passing of my father,” he recounted. “It was Shmuel Kunda who was the first to greet me with his warm smile and hearty handshake. That greeting made all the difference to me and paved the way for me to acclimate to yeshivah.”

Through the warmth of his handshake, Shmuel Kunda paved the way for a nervous young bochur who would one day become the rosh yeshivah of Yeshiva Darchei Torah in Far Rockaway and one of the most prominent mechanchim of our time.

Rebbi at Mordy’s vort

Ahead of His Time

It wasn’t just the Shmuel Kunda personality that made the camp experience so special. He may have put on hilarious skits and created the craziest stories but there was also a very specific method to the madness, a philosophy in chinuch that was far ahead of its time. Shmuel Kunda believed that for children’s chinuch to really work it has to be fun. He saw the side-splitting humor that came so naturally to him as a means to an end rather than the end itself. Using humor, enthusiasm, and boundless simchas hachaim as a backdrop to a rigorous educational program might not seem like a groundbreaking novelty today but, in many ways, it was Shmuel Kunda’s innovation.

Mordy himself was a rebbi at Yeshivas Toras Emes Kamenitz for five years after leaving kollel. “I don’t have Rabbi Kunda’s talent,” Mordy admits, “but I tried as best I could to give the kids that sense of fun and joy in learning. To this day, former talmidim, some whom are grandparents themselves, remind me of how enjoyable those classes were, and much of the credit goes to Rabbi Kunda.”

If Shmuel Kunda had a way of touching the hearts of children, it may be because the child inside of him never died.

“In many ways he was a child at heart. He loved camp. He wasn’t the kind of guy who sat in his office barking orders. He was with the guys, schmoozing about whatever interested them, fully involved in every activity. He would watch the camp plays and sometimes jump on the stage and start performing himself,” says Mordy.

Someone once made an eerie observation. Shmuel Kunda passed away at 66, a relatively young age. Still, being in his upper sixties, one would expect to see a largely greyed beard, if not laced with wisps of white. But up until the end of his life, Shmuel’s beard remained almost entirely black. The child in him, quite literally, never died.

Mordy worked hand-in-hand with Shmuel Kunda on developing great night activities, planning trips, and arranging color war breakouts. Rabbi Kunda’s originality and enthusiasm made the work fun and enjoyable. “When we couldn’t come up with a good breakout idea, he and I would charter a plane or a helicopter and either announce color war through the megaphone or dump papers over the grounds,” Mordy remembers. “Rabbi Kunda even took a stab at flying the plane himself until things got shaky, and the pilot had to pull the wheel away from him while I said Tehillim.”

But Shmuel Kunda’s influence on Naarim campers ran deeper than fun and games. When learning groups were in session, he too would learn, and he always learned the same sugyos that the campers were learning. When a counselor would walk by, he’d say “Hey! How did you learn this Tosafos?” or, “What’s pshat in this Rashi?” The conversations sometimes got heated, and young campers would turn their heads to see what was going on. And there, they’d witness a man brimming with so much talent, engrossed in a pursuit which, as his facial expression made clear, meant more to him than anything else.

Mordy’s own children. Shmuel Kunda traversed two generations, yet never got old

Family Matters

The early years in Camp Naarim predated the production of Shmuel Kunda’s first tape, but it was there that his storyteller’s star began its meteoric rise. “He would tell a story every Shabbos afternoon,” says Mordy. “Everyone would come to listen, campers and counselors alike. His stories went on and on, an hour quickly became two hours, we would have to delay Minchah to allow for the story to end.”

At some point, Shmuel Kunda felt that the storytelling gift he was blessed with had to be shared. But the truth is that although he is most famous for the albums he personally produced, Shmuel Kunda was actually featured on a different set of groundbreaking tapes: Volumes I and II of the 613 Torah Avenue series, produced by Mrs. Rivkah Neuman and Mrs. Cheryle Knobel, featured a narrator whose voice was as comical as it was unforgettable. It was back in 1977 when Shmuel was recruited for the job, and, the fact that children, to this day, will try to imitate the croaky “Don’t walk, don’t walk” whenever they pass a traffic light is a testament to his ongoing magic.

And then he began to produce his own tapes. Beginning with the Boruch series, his first two tapes were Boruch Learns His Brachos followed by Boruch Learns About Shabbos. The series continued with Boruch Makes a Simcha and, later, Boruch Learns About Pesach as Shmuel moved on to create over a dozen tapes, covering a wide variety of Torah-based subjects such as emunah, bitachon, mesirus nefesh, Hashgachah pratis, achdus, self-confidence, and simchas hachaim. The common theme among all of them is that they are funny, captivating, and filled with songs with upbeat, easy-to-sing-along music and spot-on lyrics.

One might rightfully assume that all those songs must have taken him quite some time to create. “Actually,” says Mordy, “he told me on several occasions, that most of the songs he played on his tapes just popped into his head while walking down the street in Boro Park.”

That means that “Kippah o’ Kippah” might have been composed while chapping a Minchah in Shomer Shabbos, and “Here Comes the Trolley” might have been invented while picking up a pie at Mendelsohn’s pizza. Since the songs came to him so quickly, he carried a recorder with him at all times so as not to forget them.

His daughter Mrs. Shaindy Pichey remembers how sometimes, her father would compose a song on Shabbos, when his recorder was inaccessible. “He’d start singing and instruct us to remember the song,” she says. “Usually by the time Motzaei Shabbos came around, we had already forgotten it.”

And this goes to a part of the story of Shmuel Kunda that few but his children can tell. “Our father was such a family man,” Mrs. Pichey says. “He loved taking us on family trips — we’d go on a trip every Sunday. And of course, he told us stories. He had one story called ‘The Chaim Story,’ that just went on forever. When it came time to write the scripts for the tapes, he’d come home with a stack of papers and we’d all sit around while he read to us what he wrote that day.”

The creation of the Shmuel Kunda tapes was so much of a family experience that even the older generation got involved. “My grandmother, Ita, or better known as Ida, lived down the block from us,” says Mrs. Pichey. “Her husband, Reb Zalman Kunda, had passed away many years prior, and she lived alone. She was a brilliant woman and my father ran all his ideas by her. She shepped so much nachas from him.”

Shmuel Kunda’s wife, Naomi, was also a brilliant woman, but her intellect shone in a way drastically divergent from her husband’s. “My mother was a college graduate, a valedictorian. But my father could not stand academics,” Shaindy reveals. “My mother basically did for him everything that a computer does today. She was his spell-check and his dictionary.” They were a perfect, albeit unexpected match for each other, and their inseparable bond proved itself until the end. Mrs. Naomi Kunda passed away on the 28th of Shevat, 5770 — less than two years prior to her husband’s passing on Rosh Chodesh Cheshvan, 5772.

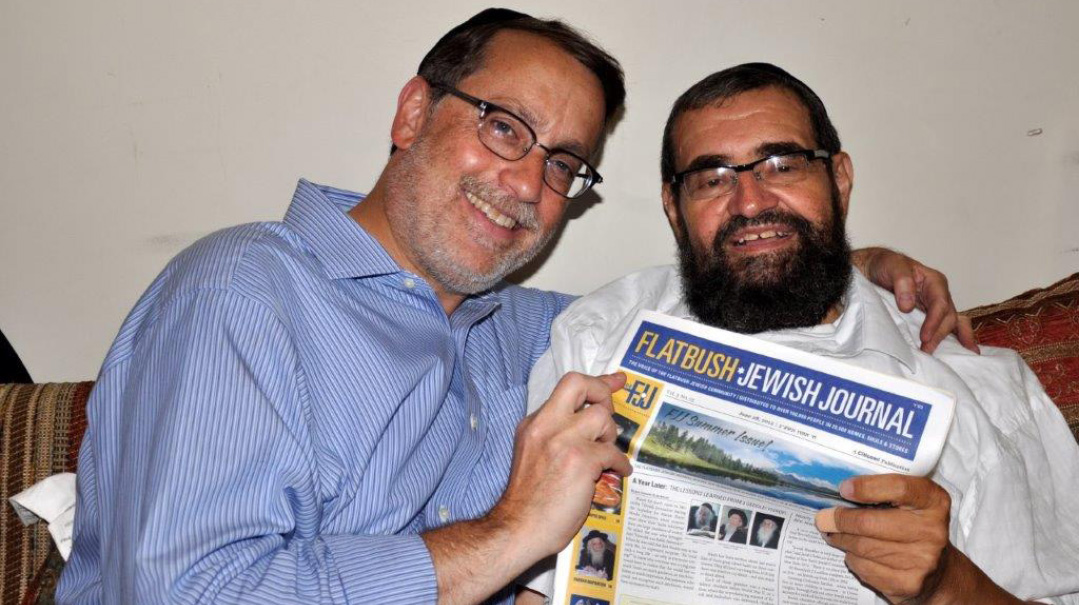

Mordy enjoying a light moment with his forever rebbi. It was toward the end of Rabbi Kunda’s life, but the joy and humor never disappeared

My Best Friend

Shmuel Kunda produced his tapes in the days before musical productions meant clicking lots of buttons on large, sleek screens with rhythmic bars jumping up and down.

“We kids would come with our father to the studio,” Shaindy Pichey reminisces, “which was first in Eli Teitelbaum’s basement, and later in a more professional studio. When the script called for the sound of pens dropping, we’d actually drop a bunch of pens. When there were people running back and forth, we would have to run back and forth.”

For the first few tapes, such as Boruch Learns About Shabbos and Feitel Von Zeidel, the Kunda children acted as the kids on the tapes. But they didn’t appreciate the fame that it earned them. “We didn’t like standing out among our friends,” says Shaindy. And so, in subsequent tapes, he sought out other children from the neighborhood to take on these roles.

Take for example, Heshy Himmelstein of When Zaidy Was Young I and II. That he was zocheh to become the hero of the Lower East Side was really to the credit of his mother. Mrs. Chaya Rivky Leiser, today an eim bayit in the Bnos Chaim seminary in Lakewood, happens to also be the alter ego of the one and only Mrs. Pitkin (“Isn’t that the place without the radiator?” “Oy, he’s got a goldene voice. And when I hear the way he does chazaras hashnapps, freg nisht!”) When Shmuel Kunda needed a suitable fit for Mrs. Pitkin, his wife recommended Mrs. Leiser. Once that was settled, she had protekziya to suggest her son, Avrohom Dovid Leiser, to play the part of Heshy Himmestein. Rabbi Kunda made Avrohom Dovid read him a book to determine whether he had the skills it would take to fill the role.

The recording experience was incredibly fun. There was no mixing tracks in those days: Everything had to be done in the studio, in the proper sequence. That meant the entire cast showed up, each behind their own partition. It sounds like a lot of people crammed into a small studio but it wasn’t really so — because Shmuel Kunda played most of the roles himself. Mrs. Leiser and her son were there, Yehudah Gutwein played Eli Himmelstein, Mrs. Chani Handler played Mrs. Himmelstein, and Shmuel Kunda played the mayor, the Italian fishmonger, Mr. Blister, Mr. Galamucci, Uncle Isadore, and many more.

“Sometimes he would get mixed up as to what voice he was supposed to be doing,” Mrs. Leiser remembers, “and he wouldn’t even realize it — he’d keep going and going in the wrong voice. So what we would do is switch our voice as well. And he’d say ‘Hey! You’re not Mrs. Himmelstein! You’re Mrs. Pitkin!’ And we’d say, ‘Yeah, but you’re supposed to be the mayor, not the pencil factory guy.’”

It was a problem, but he found a solution. He designated a different corner of the studio for each character — one place for each voice — and would spend the entire recording session running from one corner to the other.

“Rabbi Kunda did everything,” says Mrs. Leiser. “He wrote the songs, even though he didn’t play an instrument. He wrote up the script for us with each of our lines highlighted. We would read our lines one or two times before showing up at the studio but, aside from that, all we had to do was show up and read our part.”

But, as Mordy pointed out, the fun was all there for a purpose. The tapes weren’t a career shift, they were just another expression of the rebbi in Rabbi Kunda, broadcasting his message of a Yiddishkeit filled with simchah to an audience far greater than any classroom could encompass. Still, those tapes had a direct impact in the classroom as well.

“I once showed up at a bar mitzvah,” Mrs. Leiser recounts, “and when I sat down at my table, the woman sitting next to me said ‘I can’t believe you’re here, I just turned you off in my kitchen.’ A third woman seated at the table, who didn’t know who I was, gave us a baffled look. The conversation, as far as she could tell, was utterly absurd. So I explained, ‘Whatever, I’m on these tapes, put out by someone named Kunda.’ The words were barely out of her mouth when the woman shot forward. ‘Kunda? Shmuel Kunda? I teach the second-grade boys in Chofetz Chaim, and we listen to Shmuel Kunda tapes for our penmanship class!’ ”

A week later, Mrs. Leiser received 31 letters in the mail from a certain second grade class in Chofetz Chaim. Each letter contained a question about the tapes and, not knowing what to do with them, Mrs. Leiser delivered them to Rabbi Kunda. “He answered every single question and sent them back, along with a gift of little pens he had custom-made with a picture of Eli and Heshy Himmelstein running with seltzer bottles.”

Stories like these don’t surprise the Kunda children, though. “My father sincerely appreciated it whenever he was told that his tapes were being listened to and enjoyed. Even when he was already famous, he would sometimes come home, excited by the fact that someone had mentioned that he enjoyed a particular tape.”

One time, Shmuel Kunda learned that a boy named Simon was having a hard time in school because kids were taunting him, since he shared a name with the evil Simon of The Longest Pesach who wished to poison all the Jews in Prague by mixing deadly venom into the bread that would be sold on the day following Pesach.

“My father was so sad when he heard this,” says Mrs. Pichey. “He sent the boy a free CD, I think some other gifts as well.”

For Rabbi Kunda, a child being hurt as a result of his tapes was contrary to the entire purpose of their creation. “My father only wanted to build children,” says Mrs. Pichey. “That’s why, in almost all the tapes, it’s a child who ends up saving the day.” A classic example of this is The Talking Coins, where Berish, a Jewish butcher, was accused of stealing an entire box of coins from Johan, who owned the neighboring spice store. In reality, it was all an evil conspiracy by Johan who was deeply envious of Berish’s success. Many leading rabbanim gathered to discuss how they would exonerate Berish, but it was a young boy named Yehudah who came up with a brilliant strategy. The problem was, how could he get them to listen to him?

First pull your stomach in

Then you lift up your chin

Say I’ve got something to mention

Just keep on saying it — and in a little bit

You will get lots of attention

And soon every one of those menschen

Will want to find out your intention

Yes, you will get lots of attention

When you keep your spirit up high

It’s vintage Shmuel Kunda, with enough poetic license to allow for just the right amount of silliness to slip its way in. But the message isn’t silly at all. Lift up your chin, keep your spirit high, the fact that you’re young shouldn’t matter. If Yehudah can save the butcher, then you can do great things as well.

Shmuel Kunda himself stood as a shining example of someone who did great things. On many occasions, he would visit hospitals to cheer up young patients — he was always looking for ways to be mechazek and uplift. On Purim, crowds of meshulachim would gather in the Kunda home, but not to receive a handsome check — Shmuel Kunda was not a wealthy man. They came because Shmuel offered them something more valuable than money. He would sit them down and just talk to them and they walked away feeling so good about themselves. During the shivah, people would show up and tell the Kunda children that their father was “such a close friend.” In many instances, the Kundas had never even heard their names before. Numerous letters were sent as well, with complete strangers describing the various ways Rabbi Kunda brightened their lives. For the shloshim, Mordy compiled these letters into a book, along with tributes, photos, and a large sampling of Rabbi Kunda’s original artwork to serve as a keepsake for the family.

Benches are Ready

Mordy was a talmid of Rabbi Kunda as well an employee. But the bond grew ever closer when the two began learning together b’chavrusa. “He was both a talmid chacham and a great lamdan,” Mordy remembers. “He was a great baal mechadesh and would frequently come up with his own chiddushim on the sugya.”

When Rabbi Bender delivered his hesped at the levayah, after sharing his memory of how Rabbi Kunda greeted him on his first day in the Mir, he shared a vort from Rabbi Kunda — a chiddush from a creative mind, but even more so, from an enormous heart. He quoted the Gemara in Berachos (28a), stating that when Rabi Elazar ben Azarya was appointed to serve as the rosh yeshivah, he removed the guard that stood at the yeshivah’s doorway and allowed all to come and learn. The Gemara says that, “hahu yoma itosfu kamah safsali — on that day, many benches were added to the beis medrash.” Rabbi Bender said that Shmuel Kunda once questioned this peculiar language. “Why say they added benches? Shouldn’t it say they added people? Shmuel answered that it doesn’t help to bring people to a beis medrash if they don’t feel that it has a place for them. Rabi Elazar ben Azaria didn’t just let the people in, he made sure there were benches for them. His message was that somewhere in his yeshivah, there’s a place that’s ready, and perfect, for every student.”

Whether your head is round or shiny or your hair is like steel wool

I’ve got one that fits you like a glove

O if you wear it every place you go at home or play or school

It shows that you believe Hashem’s above (The Magic Yarmulke)

And that, said Rabbi Bender, was Shmuel Kunda’s essence. To let every single Jewish neshamah know that somewhere in our magnificent mission, there’s a place that’s ready, and perfect, for them.

ROUND TWO

Shmuel Kunda was both an educator and an entertainer, and while he didn’t offer any accredited courses to aspiring storytellers, he has influenced practically all of them. Even in recent years, contemporary talents look to Shmuel Kunda’s work for inspiration, including the indefatigable Shimmy Shtauber. Shimmy (which, for the record, is a stage name) is a voice impersonator par excellence, but he, like his mentor, looks to channel his G-d given abilities specifically toward projects that will help inspire, teach, and illuminate. When he’s not producing in the studio, he’s busy pursuing his true passion — the field of chinuch. With his finger on the pulse of the most contemporary challenges, he guides and works with struggling youth and their parents, from across the frum spectrum and puts a special focus on crisis prevention. But, like his mentor, it’s all done with so much fun, love, and humor. Since Shmuel Kunda’s passing, Shimmy has released multiple “Shmuel Kunda” albums with voice impersonations that sound uncannily like the real ones. Shimmy shares his take on how, even a decade after his passing, Shmuel Kunda continues to lead the ever-growing industry of Jewish children’s entertainment.

Shimmy, can we share your real name, or, if not, can you tell us why you choose to hide it?

“No problem. Actually, my name is Yehuda Kanner. It was never really a secret, I was just never comfortable putting my real name on the albums, as I always just considered myself a shaliach trying to bring out someone else’s art to the public wherever I felt it would be appreciated.”

Were you a long-time Shmuel Kunda fan?

“Well, in terms of time, I was practically born listening to Shmuel Kunda tapes. We have old fuzzy family videos on VHS of me learning to crawl, with Shmuel Kunda tapes playing in the background. Like probably most of my generation, I can’t remember a time not listening to them.”

Did you ever meet Shmuel Kunda in person?

“Yes. We actually shared a common relative — he was a cousin of an uncle of mine. When I was 12, he stayed with them once when he came to my hometown of Toronto for a simchah, and that’s when I got to meet him.”

When did you first conceive producing your own “Shmuel Kunda” tapes?

“Shortly after Shmuel Kunda’s passing, I released an album called The Story Experience together with Rabbi Nachman Seltzer. Since we were still recording when we sadly learned of his passing, we included an audio tribute to him at the end of the album in which I performed impersonations of a few of his famous voices. Through that, I was put in touch with the Kunda family, and we started discussing the production of a new posthumous Shmuel Kunda album.”

Were the stories your own ideas or were they based upon Shmuel Kunda notes?

“So, the first project we did, When Zaidy Was Young 3, was largely based on a script that he himself had written. Interestingly, it was the very same idea that he told me about in person when I met him as a kid. After that, when we continued the Boruch series, I collaborated with an extremely talented friend of mine, Rabbi Abba Wolk — I’ve never met anyone who has as proficient an understanding of Shmuel Kunda’s style and art than Rabbi Wolk. He wrote most of the scripts and songs for the new Boruch albums, and we produced them based on that.”

How did it work practically? Was the Kunda family fine with you mimicking the legendary Shmuel Kunda voices?

“The Kunda family was always involved in the productions of the albums. In fact, it was really their products. They essentially just hired me to put them together.”

How many Kunda CDs have you put out so far?

“Five. There’s When Zaidy Was Young 3, Boruch Learns About Sukkos, Boruch Learns About Chanukah, Boruch Learns About Purim, and a Yiddish version of The Magic Yarmulke called Dus Vinderliche Yarmulke.”

Between writing the scripts, putting the music together, and finding the right actors and voices, how much time do these projects take?

“It depends on a wide variety of factors — there’s no definite timeline. When Zaidy Was Young 3, for example, took about a year from start to finish, while Boruch Learns about Sukkos took under two months.”

What, in your mind, stands out as so unique about Shmuel Kunda’s talent?

“I tried to uncover the answer to that question myself for years. I find that pretty much every Kunda fan has their own take on why his work had such an impact. I think a big part of it was the authentic feeling of warmth, fun, and light-heartedness that comes across, even while portraying the heavier or scarier aspects of a story.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 933)

Oops! We could not locate your form.