When Our Questions Melted

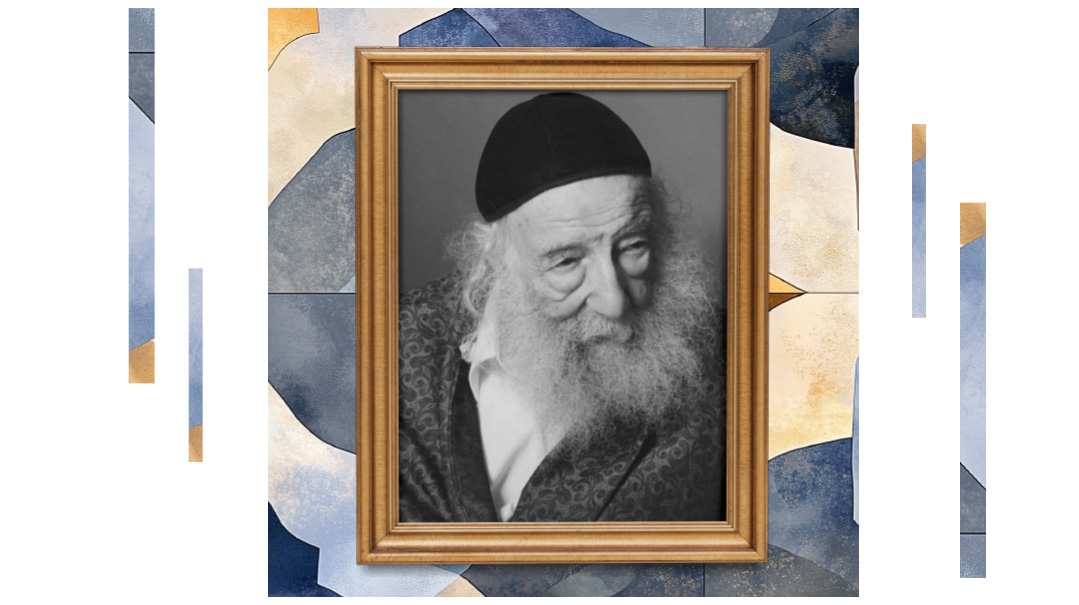

| January 22, 2020Mourning halachic master Rav Pesach Eliyahu Falk

The term “baal halachah” is occasionally used, but it’s rare to see a human being whose entire life is not just governed by halachah, but who lives it, breathes it, sees it as a sacred mission to pass on to everyone he possibly can. Rav Pesach Eliyahu Falk was a baal halachah.

My first introduction to Rav Falk was on a Friday morning, my first week in Gateshead Seminary. He told us he’d be teaching us hilchos Shabbos, and said we’d be starting with an overview. But first, he said, he needed to teach us two halachos that he’d seen, over the years, many girls were unaware of. And because we were doing the melachos in order, and these points were a toldah of a melachah that we’d only learn the following year, he wanted us to learn them immediately.

He then taught the halachos, and to my dismay, I realized I had unwittingly been mechalel Shabbos d’rabbanan for years. Around the room, I saw similar looks of incredulity and distress.

That Friday, as girls called home, I heard them telling their mothers the halachos we had learned. And I got a taste of the urgency, the primacy of halachah. A Torah Jew needs to know how Hashem wants us to live. If they don’t, they will err and stumble, unknowingly loosening their connection to our life source. So halachah must be learned, and absorbed, and immediately put into action. This is what Rav Falk transmitted to us.

We felt it in the way he taught. He would explain the same concept again and again, in a half dozen different ways, if even one girl was struggling to understand. He never settled for us “basically” knowing what to do. We had to know it absolutely. Because this wasn’t about learning; it was about living. And you have to know how to live!

Rav Falk was the last person who would encourage women to learn Gemara. And yet, when it came to particularly complex melachos, he would sometimes take us back to the source, explaining the machlokes in the Gemara.

“I don’t want you to just memorize a bunch of do’s and don’ts,” he said. “If you learn that way, you’ll forget. I want you to understand the roots of the issur. Once you know that, all the many details that follow will make sense. You’ll see them as part of a whole, and you’ll be able to learn them more easily, and, most important, remember them for life.”

That was the goal: to learn so we could live.

Learning hilchos tola’im, the laws of forbidden infestation, from Rav Falk gave us a taste of authentic yiras Shamayim. When he would talk about how many thrips you could find in a lettuce leaf, in a single strawberry, you saw the fear, the horror at the thought of unwittingly ingesting something forbidden. And that made you want to be meticulous as well.

During my very last term in Sem, I was zocheh to be the “dinim rep.” It’s a job that includes sharing a halachah each day at lunchtime, and serving as liaison between the students and Rav Falk. While every girl was welcome to approach the Rav with her own questions, many felt too shy to do so, and preferred to give their question to the dinim rep, who’d present it to Rav Falk. Additionally, there were girls who had been in seminary years before who’d call and give the dinim rep their list of sh’eilos.

Every morning, during the 20-minute break between the second and third class, I’d meet with Rav Falk behind the T3 classroom, pull out my little pad, and present him with anywhere from two to fifteen questions. The questions ranged from kashrus to Shabbos to ona’as devarim to brachos to tzniyus.

Every question got a clear, measured response. If Rav Falk wasn’t entirely sure what the girl was asking, he’d have me go back to her and clarify, to ensure his response was perfectly calibrated to the question. No question was ever deemed too small or too silly. There was no element of life halachah didn’t address.

There was a theological issue I’d grappled with for years. I’d presented my dilemma to a number of my rebbeim. All of them had answers, some long and detailed. Each answer did address the question — but not fully. I was left unsatisfied, still seeking.

It had never dawned on me to approach Rabbi Falk with the question. He was the halachah rav, the man who told you what to do, not what to think. But once I became dinim rep and started realizing the incredibly vast reach of halachah, I decided to ask him the question.

After I voiced what was bothering me, there was a long pause. “I’d prefer not to respond to such questions,” Rabbi Falk finally told me frankly. I stared at the floor.

“But since you already have the question, it needs an answer.”

He then proceeded to give me a brief, three-line answer. And for the first time, my question was laid to rest. The baal halachah could define reality in such a way that questions melted.

Slowly, I started turning to Rav Falk for answers in other areas in life. He treated questions about life decisions exactly as he did halachic sh’eilos — make sure you fully understand the issues, weigh the options, then figure out what is ratzon Hashem and follow that path.

It sounds so simple, while reality can be messy. But for him, it truly was that simple. What does Hashem want? was not just a slogan; it was the bedrock of his existence. And when you were in his presence, you felt that sense of purpose.

Two years ago, I was visiting England and traveled up to Gateshead for a single day, attending classes in the seminary. I sat in a darkened room looking at slides of various bugs as Rav Falk taught his hilchos tola’im class. And there was a joy in knowing that in a world with increasingly murky values, there was a place, a person, who personified such clarity and conviction.

Now he is gone, his voice silenced.

But as thousands and thousands of students prepare our tea in a kli shlishi, as we judge how much we can eat at a kiddush before being mechuyav to wash, as we carefully check our rice, as we live a mundane, physical life being aware that our every action is important and reverberates Above, he will live on within us.

Yehi zichro baruch.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 795)

TEST

Oops! We could not locate your form.