When G-d Says No

| November 1, 2022Tears, unity, and prayer echo in the Arab hovel where abducted soldier Nachshon Wachsman Hy”d was killed nearly three decades ago

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Flash 90

IT was Friday, 9 Cheshvan (October 14) 1994, as the nation held its collective breath, unified in prayer for a miracle — or at least a daring IDF rescue — after 19-year-old Golani soldier Nachshon Wachsman Hy”d was abducted and held for nearly a week at gunpoint by his Hamas terrorist captors. The deadline for his execution — eight p.m. Friday night — was approaching. Would Israel capitulate to Hamas’s demand for the release of Sheikh Ahmed Yassin and another 200 terrorists from Israeli prisons in exchange for Nachshon’s life?

Yehudah Wachsman a”h, Nachshon’s father, begged the nation to daven — in fact, over 100,000 people of all religious stripes and types converged on the Kosel to pray for his safety. His mother, Esther, pleaded with women in Israel and around the world to light an extra Shabbos candle. In the end, as we know, Nachshon was killed by his captors during a brave but failed rescue attempt by IDF commandos. And, as his rosh yeshivah famously said at the funeral, “Hashem hears every prayer, but just as a father always wants to say ‘yes’ to his children’s requests, sometimes he must say ‘no,’ even if the child doesn’t understand why. Hashem heard our prayers, and for some reason that we don’t understand, this time He said ‘no.’”

Today, with the approaching yahrtzeit, we’re heading to the village of Bir-Nabala, back to the still-abandoned house where Wachsman was held and eventually murdered, where officer Nir Poraz was killed and seven other soldiers wounded during the rescue attempt. The village is just a few minutes outside of Jerusalem, but we have a military escort as it’s over the fence in Area C, and these days, especially with Israeli-Arab tensions taut and security forces on high alert, it might as well be a different universe.

We’re joined by Major Gen. (res.) Nitzan Alon, who at the time was commander of Army Intelligence’s elite Sayeret Matkal reconnaissance unit, the rescue force that charged in on the captors 28 years ago. We’ve also asked Chezi Wachsman, Nachshon’s brother, to join us — he’s never been back to the captivity house before, nor has he ever seen the couch where his brother was held, and eventually murdered. Chezi doesn’t come alone, though. He brings along a close friend and fellow bereaved brother named Itamar Moreno.

Itamar is the brother of Lieutenant Colonel Emmanuel Moreno, a”h, who fell at the end of the Second Lebanon War in 2006 while in General Alon’s brigade. Moreno, a religious soldier who’d served in mostly undisclosed capacities within Sayeret Matkal for 15 years, had taken part in the greatest number of operations in the unit’s history, and was considered the single most prized soldier in the entire IDF. He left behind a wife and three children.

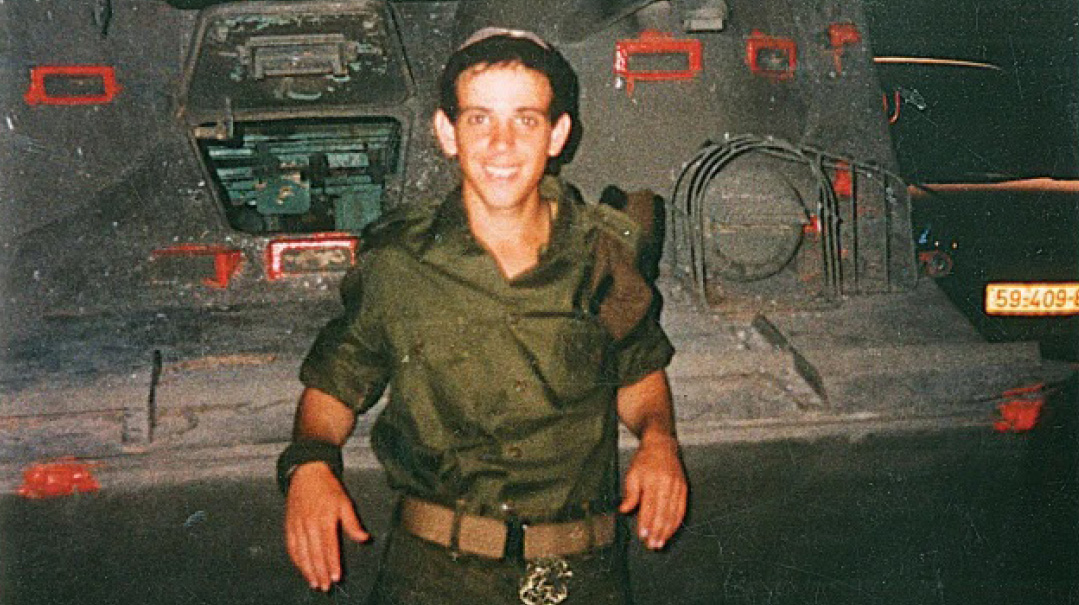

Nachshon Wachsman Hy”d. Hamas’s gift to the winners of the Nobel Peace Prize

In fact, the operations Moreno was involved in were so secretive and sophisticated that until today, 16 years after his death, the details of most of those missions are still under a gag order and military censors continue to ban the publication of his photograph — making him the only soldier in IDF history whose picture can’t be published even posthumously.

Chezi and Itamar have become close friends with both each other and with General Alon — the three of them joined by tragedy. Alon, a longtime decorated fighter and national hero who eventually served as head of Military Intelligence and later as the head of the IDF Central Command, was in the shadow of both of their deaths as commander of Sayeret Matkal. He shares their pain — and he, too, is connected with the blood of their loved ones, the losses of the Wachsman and Moreno families intertwined with his own courage and battle scars.

General Nitzan Alon (right) shares his memories with Itamar Moreno, and Chezi Wachsman, and Mishpacha’s reporters. After 28 years, the house is still standing, its same sooty walls and burnt sofa frame remaining after the terrorist firefight with IDF commandos

Fallen Brothers

When the Second Lebanon War broke out in the summer of 2006, five weeks of fighting ensued, during which time Prime Minister Olmert refused the demands of the American administration for a ceasefire before there was a decisive outcome. Just before the intense external pressure forced him to adopt UN resolution 1701, a special force was sent in, overseen by General Nitzan Alon, to reconnoiter intelligence and weapons in the Baalbek region.

On August 18, 2006, two Yasur helicopters landed in the valley and let out some 200 IDF fighters disguised as Lebanese soldiers. They were there for a few hours and successfully completed their mission before turning back toward Israel’s border. But something went awry, and the fighters were exposed.

By then a ceasefire had already been called, but that didn’t prevent a Hezbollah ambush as terrorists opened fire on the retreating military vehicles. Emmanuel Moreno, who had survived countless dangerous operations, was killed.

A fellow soldier and friend who also took part in the operation later recounted their final conversation: “We sat down and spoke about all sorts of scenarios,” he told reporters later. “And then Emmanuel turned to me and said, ‘What would you do if a missile hits us and we have five seconds left to live?’ I told him I would close my eyes and wait for it to be over as quickly and painlessly as possible. He said that what we need to do in those five second is recite Shema Yisrael. He said that if a person has five seconds left to live, these are the most significant seconds of his life, and if a person doesn’t understand the significance of his final five seconds, what kind of meaning did his life have?”

Itamar Moreno can’t go back to the Baalbek valley to commemorate the memory of his fallen brother. What he and his brother Shmuel did do was to establish a lookout in the Shomron in Emmanuel’s memory, and they’ve also created an organization called “Ha’achim Shelanu” (“Our Brothers”) for siblings of bereaved families. Through the organization, he and Chezi Wachsman have become close, never missing an opportunity to perpetuate the memory of their fallen brothers.

We’re about 15 minutes outside Jerusalem, on the outskirts of the village, when the driver stops in front of a crumbling building that looks like it could be it. But General Alon remembers the scene like yesterday. “Nope, this is not the house,” he says with certainty. A minute later, he tells the driver to stop. We’re now standing in front of an abandoned house, its windows sealed up, its yard overgrown with weeds. Only the fig trees seem oblivious to the surroundings: They’re blossoming and look as fresh as can be.

“This is the house,” General Alon whispers. This crumbling hovel is the place that threw the entire country into turmoil.

Yehudah Wachsman, who passed away in 2020, watches as Nachshon pleads for his life in a Hamas-produced video clip

Too Late to Escape

In the fall of 1994, Yitzchak Rabin, Shimon Peres and Yasser Arafat were about to win the Nobel Peace Prize for the Olso Accords between the State of Israel and the Palestinian Authority. But mainstream Israelis weren’t the only ones horrified by the ill-fated agreement — so was the nascent Hamas terror organization, who set off a string of terror attacks in order to torpedo the deal. On the one hand, buses were exploding around the country, and on the other, the atmosphere of a promised peace was hovering in the air. This was the setting, and the Wachsmans, US citizens living in Jerusalem, were going to play the main role.

On 4 Cheshvan, October 9, soldier Nachshon Wachsman, a fighter in the Orev-Golani unit, was at home in Jerusalem on leave, when he was instructed to attend a one-day training course in northern Israel. He left home on Motzaei Shabbos, telling his parents he’d return Sunday night. After the course, he was dropped off at the Bnei Atarot junction not far from Ben Gurion Airport, where he could either catch a bus or hitchhike back to Jerusalem, a common method of travel for Israeli soldiers.

A car with four people wearing yarmulkes and playing chassidic music, with a Tanach and siddur on the dashboard, stopped for him. Only after he entered the vehicle did Nachshon realize that they were Hamas terrorists.

But then it was too late.

In a security briefing with chief of staff Ehud Barak

The next six days remain etched in the collective Israeli consciousness like a suspense movie with the worst ending imaginable, an end that has echoed since in every hostage deal with terror organizations.

“Nachshon was supposed to come home on Sunday evening,” his brother Chezi recalls. “My parents waited for him. But nine o’clock came, and then ten, and he didn’t arrive. They called the ketzin ha’ir, the city’s military headquarters, but were assured, ‘There’s nothing to worry about if it’s only a few hours.’ They did worry, though, because Nachshon was a very responsible type.”

That night, the Wachsmans couldn’t sleep. They waited for morning to come so that they could tell the ketzin ha’air that an entire night had passed, so now a search could begin. “Monday morning arrived,” Chezi continues, “and we didn’t hear from him. As the daughter of a Holocaust survivors — she herself was born in a DP camp — my mother worries a lot. She was sure that if he didn’t call, there could only be one reason: He couldn’t.”

It would take almost another day for Wachsman to appear on the screen in his parents’ home. After tense hours of uncertainty, dread and an expansive search operation, a video tape was sent from Gaza in which Nachshon was seen pleading for his life and begging his parents to work for his release. “The guys from Hamas abducted me,” he said facing the cameras, a Kalachnikov rifle pressed to his neck. “They want to get their prisoners released. If not, they will kill me. I’m fine now, and hope to get home to you, if Rabin decides to release their prisoners.”

Yehudah and Esther Wachsman urged Prime Minister Rabin to enter negotiations; to them, Rabin was polite but noncommittal, but behind the scenes, he sent agents to sniff out possible avenues of communication. He also instructed the Shin Bet to focus all its efforts on intelligence leads to find out where the captured soldier was being held. The assumption was that he was somewhere in Gaza, and Rabin had the entire Gaza Strip sealed off. He also called his “peace partner,” Yasser Arafat, and put full responsibility for Wachsman’s well-being in Arafat’s lap. Arafat, delighted at the opportunity to embarrass PA rival Hamas, responded by denouncing the abduction and announcing that the PA was committed to finding him. In fact, over the next few days, Arafat — having been granted an excuse to hit Hamas — began cracking down and arresting dozens of Hamas members.

Israel, meanwhile, forced Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, the Hamas leader imprisoned in Israel, to instruct the abductors, in front of the cameras, to release the soldier. “I suggest in such cases not to kill the soldier and to reach an agreement,” he said in a video that was disseminated by Israel.

“Very nice,” thought the captors. “Israel forced him to say that.”

As the days went by, the political and security echelons realized that the only viable approach was the military one. The demands presented by the abductors were totally unrealistic.

At Nachson’s fresh kever several weeks later, with foreign minister Shimon Peres and US president Bill Clinton, who was in Israel for the signing of a treaty he helped broker between Israel and Jordan

Closer than We Thought

It was Thursday night, and in another 24 hours, the ultimatum would expire. If, by then, Israel had not released the prisoners on the list they had submitted, Nachshon Wachsman would be killed.

Just then, the Shin Bet got its hands on the golden nugget of information: They captured Jihad Yamour, the driver of the rented car that had picked up Wachsman. In a “rapid” interrogation authorized by the state prosecutor, they learned that Nachshon was not in Gaza. He was being held in a Palestinian village just ten minutes from his home in Ramot. At that point, Rabin authorized a military raid.

“We were training for an operation in Syria at that time,” says Nitzan Alon, who was a commander in Sayeret Matkal at the time. “We returned very early on Friday morning, and immediately we were told, ‘Get ready.’ We didn’t have a lot of time, so we did a quick study of the situation, gathered the anti-terror equipment we needed, and were off to the Ofer army base where we met up with military intelligence officers and people from the Shin Bet.”

While Hamas had worked hard all week to create the impression that Wachsman was being held in Gaza, there was one Shin Bet operative who didn’t buy it.

“Gideon Ezra, who was head of the district in the service,” Nitzan Alon recalls. “He said the whole time that something didn’t smell right to him, and insisted his men focus instead on the Jerusalem area. They were looking for the vehicle that had transported the abductors. They went to every car rental in the country, and put together shreds of information. And then they got a ‘bingo.’”

On Friday, while the clock was ticking toward the ultimatum, Rabin, Peres and Arafat made the announcement that they’d won the Nobel Peace Prize. When Peres was asked his opinion on the “peace” that he had achieved in light of Hamas’ impending deadline, he responded that the peace process involves “calculated risks.”

On Friday afternoon, Hamas once again threatened, but with an hour’s reprieve: If by nine p.m. on Friday night Israel would not release the prisoners, the soldier would be killed.

“We realized that we were under tremendous pressure with a very short range of time for action,” General Alon recalls. “In rescue operations, it’s always best not to get to the time of the ultimatum, because the abductors are much more tense by then. So we agreed that we’d converge on the area between seven and eight, before they began to get organized.

“At the same time, there was a team of embedded forces disguised as local Arabs who were planning out the route. We didn’t want it to appear that any IDF vehicles were coming from Israel’s side, so we planned a route via El Jib, through the center of the village, so that if someone was watching, they would think it was a routine patrol.”

The rescue force was made up of three units. Some of the soldiers were embedded in the local population, some pretended to be on regular IDF patrol, and others were brought in a truck that unloaded them in an olive grove, from where they walked to the destination.

The plan was to storm in from the three entrances of the house at the same time: One team, headed by Lior Lotan, would burst in from the front door; another team, commanded by Nir Poraz, would burst in from the porch to the kitchen and a third, commanded by Nitzan Alon, would come in through the roof.

The entry was timed to be simultaneous. A small whisper on the radio — “break-in” — and three explosive devices were supposed to blow open all three entries at the same time.

We’re now standing in that very courtyard. Nitzan Alon walks with us to the left of the house. Two floors and a roof. “Here,” he points, “we put a ladder and climbed to the roof.”

Weren’t they afraid they’d be spotted?

“Not really,” Alon says. “We knew that the abductors were hiding not only from us, but also from the neighbors. From the whole village, in fact. They didn’t want anyone to know they were here, for fear that someone, maybe a Shin Bet agent, would be informed. So meanwhile, all was quiet.

“It was the type of operation where no one in the area knows something is happening. The house was abandoned — the owners were not in the country, and everything was locked. The terrorists also put blankets behind the shutters so no light would emerge and kept everything very silent, so the neighbors wouldn’t notice that anyone was in the house and report to the Israelis something was up.”

The element of surprise, says Alon, is always the name of the game. “The idea is to get to the abductors in the first few seconds, before they realize what’s happening. We knew that if we missed that window, the first thing they would do would be to shoot Nachshon. So there’s an approach that says: Enter through all the entryways at once, even if it contradicts the battle warfare principles of never running toward each other with weapons.”

Fifteen fighters quietly approach the three entry points — the front, the back through the kitchen, and the door on the roof. Each one of the teams had accompanying sappers who were supposed to activate the explosive devices that would bring down the steel doors. But then, a second before, they heard a whisper on the radio: “Stop. Someone’s going into the house.”

It turns out one of the captors was bringing in food. “We deliberated whether to use the chance to enter with him but decided against it,” says Alon, conceding that it was a huge mistake. Had they burst in with him, the operation would not have gone awry the way it did, and the element of surprise would have allowed them to get to the soldier. “It’s the wisdom of hindsight,” Alon sighs.

When the food delivery person left, the backup Duvdevan force that surrounded the house apprehended him for an on-the-spot interrogation. The good news was that Nachshon was still alive.

“We quickly tried to get some more information out of him about the structure of the house, but there was no time to reprocess everything. The devices and the forces were all in position and we began the countdown to the break-in.”

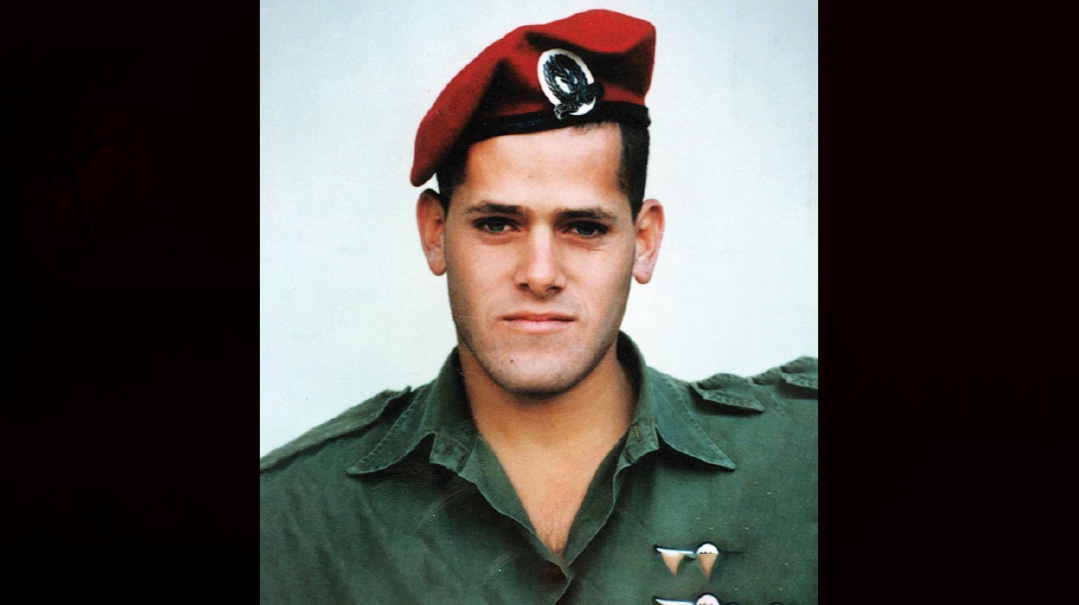

Nir Poraz Hy”d (top) charged into the room where Nachshon was being held, only to be felled by a hail of bullets

A Minute too Late

We enter the house, and it’s as if Alon is transported back 28 years. Everything looks the same: the sooty walls from the fire that broke out during the exchange of gunfire, the scorched sofa frames. Underneath one of them, the one Wachsman was tied to, are iron chains, bullet casings, and the only sign of life: a small snake that appears for a moment and then slithers away.

Why wasn’t the house demolished, as is standard protocol?

“The owner,” General Alon explains, “was not involved. He’s a Palestinian who lives in America. A Hamas accomplice came to him a long time before the abduction and rented the house from him. They’d been preparing the place for weeks. Afterward, the owner realized it was better for him to just stay away.”

Now Alon stands in the abandoned hallway and describes the moments as if they are happening. “Nir Poraz was supposed to storm in from here, the kitchen, and from there, the front door, Lior Lotan was supposed to come in. I was supposed to come from upstairs.”

The hole in the rooftop door, blown out by a charge of TNT, was Alon’s point of entry

They all stood and counted down to synchronize their entry. But something went wrong: The front door was solid steel, and the first explosion only dented it, which meant the commandos immediately lost the element of surprise, giving Nachshon’s captors time to shoot him dead and position themselves for a shootout.

“I heard an explosion and wanted to storm in, assuming all the doors exploded together, but the synchronization wasn’t accurate and my door hadn’t exploded yet. The sapper standing behind me caught me by the vest and pulled me back. At that second, I felt a huge force and searing heat and then the door exploded. A few inches closer and I would have been finished off. That sapper saved my life.”

Alon didn’t realize that the first charge downstairs didn’t take down the door, and that it would take more than a minute to set another charge that would finally blast it open, a minute where so much went wrong.

“At that point,” he says, “we heard gunfire from downstairs, and I knew that something was not going right.”

Bullet casings from the shootout were still scattered on the floor

We Tried, We Failed

Alon and his soldiers abandoned the roof, jumped two stories to the ground, and leaped to the kitchen entry.

“Nir Poraz came in from here with his team,” he says. “There were ten soldiers running behind him, and from the moment he heard the explosion, he charged ahead, determined to reach Nachshon. He ran and got to the doorway of the room, just as one of the captors locked the door from the inside. He began to kick the door and got a bullet to the chest.”

Poraz fell in a pool of his own blood. Another officer in the unit, Itai Granot, stepped around him and approached the door. He was also shot — one bullet in the hip and another in the hand. A few very long seconds passed until Alon’s team came. When they entered, they were met with a hail of bullets from another room in the house. Only then did they realize that there was a third terrorist ambushing them from the opposite side.

“Several soldiers were already injured — anyone who ran toward them was shot,” Alon says. It all happened within seconds, until Nitzan Alon identified the source of the gunfire and liquidated him.

Nitzan Alon (left), Chezi Wachsman, Itamar Moreno, and a group of soldiers outside the abandoned house that still holds the most painful memories

Then Nitzan Alon and Lior Lotan charged forward toward the locked door, calling for the captors who hadn’t been killed to surrender. If they would release Nachshon, they would remain alive. The terrorists replied that they had no intention of doing that. “The soldier is already dead, we don’t care if we die!” one of them shouted.

“At that point, we made the decision to break the door,” Alon recalls. “Lior threw a grenade and I kicked at the door and burst inside, while the group pushed past the furniture the terrorists used to barricade the door.”

There was another exchange of fire before the room was secured. In total, three terrorists were killed and two taken prisoner, while the leader of the commando team, Captain Nir Poraz was killed and nine additional commandos wounded.

Suddenly the room was silent, Captain Nir Poraz — Nitzan Alon’s close friend and comrade – was dead, and Nachshon Wachsman was slumped on the couch, handcuffs on his hands and feet and metal chains shackling his entire body, with point-blank gunshot wounds to his throat and chest.

“I thought to myself at those moments,” Alon says, “about how great is the power of the Jewish nation’s responsibility for one another. We didn’t know each other — he and I came from very different worlds, but in order to return him home safely, I, and the rest of the soldiers with me, were willing to risk our lives. We tried. We failed…”

Chezi Wachsman goes over to Nitzan Alon and puts his hand on his shoulder. Alon is not a religious man by any stretch, but Chezi doesn’t care. “You didn’t fail,” he says, echoing those now-famous words. “Hashem said ‘no.’”

Chezi and Itamar turn to each other, look around the room, and count the soldiers positioned outside. “Hey, I think we have a minyan!” they say. The soldiers are happy to join for Kaddish and a perek of Mishnayos. Here, in the abandoned, filthy room where Nachshon was held and where his soul departed, where no one has stepped for 28 years, there is finally a sense of closure as the words ring out, “Yisgadal veyiskadash Shemei Rabbah…”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 934)

Oops! We could not locate your form.