When Dogevezh Nearly Went Dark

| March 11, 2025A surprising solution arrived at the yeshivah’s doorstep almost immediately after Rav Doniel’s return

Title: When Dogevezh Nearly Went Dark

Location: Dogevezh, Lithuania

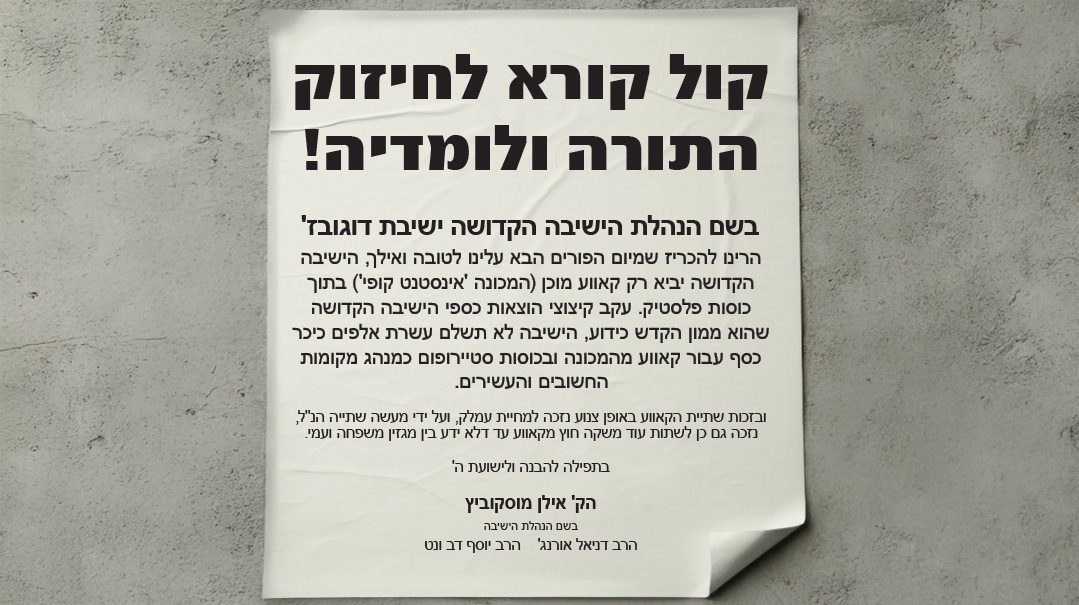

Document: Kol Korei from Yeshivah Gedolah of Dogevezh

Time: 1920s

The yeshivah in Dogevezh in northwestern Lithuania was one of the prominent yet forgotten prewar yeshivos. Rebuilt after World War I and split off from a rival yeshivah in the same town, its mission statement was to make Dogevezh great once again.

The new yeshivah initially trumped other yeshivos in the region. The rosh yeshivah, Rav Doniel Orange, was a talented maggid shiur and a very successful fundraiser, but eventually he fell into disfavor with the bochurim and the local townspeople and departed the yeshivah in 1920. It wasn’t long before Rav Doniel made it clear that he was extremely dissatisfied with the situation — and still referred to himself as the Dogevezher rosh yeshivah — even going so far as to say that yeshivah was stolen from him.

While Rav Doniel’s replacement came highly regarded, his open-door policy led to the yeshivah filling to the brim, with the vast majority of the new arrivals arriving illegally, crossing the sealed border that divided interwar Poland from Lithuania. Fatherly figures on the yeshivah’s new faculty graciously welcomed these newcomers without even asking them to take a basic farher and immediately provided them with a weekly allotment of 35 zlotys and accommodations in a local hotel. Oftentimes, despite the financial constraints facing the yeshivah, these new refugees were provided with more resources than the local talmidim, which generated resentment.

As the yeshivah’s economic situation began to deteriorate, the talmidim and executive committee of the yeshivah decided that with all of Rav Doniel’s weaknesses, they needed to bring him back; otherwise, the yeshivah’s debts would force its closure. Rav Doniel accepted the offer and upon the recommendation of his son Binyomin (fondly known as Reb Ben), invited a young prodigy named Rav Yosef Dov Vanetsky to serve as segan rosh yeshivah. Their first task was to clean up the yeshivah’s deficit — which was growing daily.

A surprising solution arrived at the yeshivah’s doorstep almost immediately after Rav Doniel’s return. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, many Lithuanian Jews had migrated to South Africa, forming the nucleus of the South African Jewish community until this very day. Despite their tenuous connection to a religious lifestyle following their migration, many families maintained a connection to their former communities in the “alte heim.” Some of them even sent their sons to study in the great yeshivos of Lithuania, much like some American yeshivah students did during this same time.

At around this time, a yungerman from South Africa named Reb Ilan Moskowitz arrived in the yeshivah. A brilliant prodigy, he was a financially successful and brilliant engineer of horseless agalos (wagons), which revolutionized the age-old modes of transportation in South Africa. He then dabbled in some other local ventures, including a newspaper — until he finally realized that he wanted to devote the rest of his life to Torah.

So in 1924, he embarked with his family of 14 on the last ship out of South Africa headed for the backwaters of Lithuania. He arrived at the yeshivah and was administered a farher by the rosh yeshivah. Surviving notes from the rosh yeshivah’s ledger read, “A great genius, but has trouble focusing. Very spaced out. Also did not wear hat and jacket to farher.”

Reb Ilan Moskowitz was quite an observant fellow and quickly took notice of the yeshivah’s desperate financial straits. He realized that if he couldn’t be a fit in the beis medrash, he could at least use his business acumen to help the Dogevezh Yeshivah get back on its feet. He approached Rav Doniel, who immediately accepted the offer, and the pair got straight to work.

Reb Ilan began to review the yeshivah’s bloated budget. With energy and passion, he rooted out the yeshivah’s wasteful spending on extracurricular activities, even including financial assistance the cash-strapped yeshivah had been providing to other even more desperate yeshivos in the region to draw them to the mussar movement. In consultation with the rosh yeshivah, they decided to do away with the Yeshivah Aid Society and prioritize the immediate ruchniyus needs of their own yeshivah, and forgo all unnecessary expenditures that had been added over the years. But that was hardly all — Reb Ilan was just getting started.

Decades prior, the yeshivah had begun providing funding to a satellite kollel, Kedoshei Kremenchuk across the border in Ukraine. Reb Ilan began to probe the finances of this kollel and discovered that the rosh kollel, Rav Velvel Zelenkovsky, was living an extremely lavish lifestyle and could not account for much of the 1,500 zlotys it was receiving each year. That same day, Reb Ilan informed Rav Doniel — who decided to invite Rav Velvel to the yeshivah under the guise of a Shabbos of chizuk. Rav Velvel immediately accepted.

On Erev Shabbos, as was the minhag for guests, Rav Orange invited the rosh kollel for toameha along with the Dogevezh hanhalah. Initially, the atmosphere was cordial, until Rav Doniel pulled a contract from his pocket and handed it to the rosh kollel to sign. The contract stated that the rosh kollel agreed that he would send a strong handful of 14 of his finest yungerleit from Ukraine to Lithuania to make up the nucleus of a new kollel being formed.

Caught by surprise, Rav Zelenkovsky grew angry and began to challenge his old friend Rav Yosef Dov, the segan rosh yeshivah, whom he thought to be behind the plan.

“J.D., I appreciate your hospitality — but we’ve spent many years and vast resources developing these gems. They belong to us!”

Rav Orange became incensed. “J.D.? Is that the type of respect you show a rosh yeshivah? J.D.?!” he snapped, voice trembling. “We’ve poured millions into your kollel, and what do we have to show for it? We’re trying to help your kollel thrive, and yet you waltz in here with such chutzpah! Maybe it’s time you showed appreciation for the 3,500 zlotys we send you each year!”

Rav Zelenkovsky raised a conciliatory hand, but it was too late. Rav Doniel Orange stood up and began to shout at him “If you can’t show basic respect, maybe it’s time to reconsider our investment in your kollel altogether.”

The dramatic standoff prompted fierce debates among talmidim — some taking the side of Rav Doniel Orange and others criticizing his behavior as reckless brinkmanship that threatened the choshuve Ukrainian kollel.

Meanwhile, Rav Zelenkovsky declared, “Our kollel will continue to learn, with or without the support of Rav Doniel.”

That very night he penned letters to leading balabatim in Ukraine and countries as far away as France, England, Germany, and even faraway Brazil, announcing the formulation of Keren Kayemet Kollel Kremenchug — an initiative he hoped would raise 100,000 zlotys to save his beloved mosad.

Another initiative of Rav Ilan was to put an end to an old program launched by the previous mashgiach Rav Yosef Liberalin. Noting the sparse attendance at the yeshivah Shacharis on a daily basis, the mashgiach had hired several assistants to wake up the bochurim every morning. “Everyone must be woken up, and we spared no expense to ensure that every talmid woke up every day.”

Although acknowledging the marginal benefits to this woke program, Reb Ilan Moskowitz declared, “The yeshivah isn’t all about checking if everyone woke up. We have more important priorities we must focus on with our limited resources.”

Chief of the Chassidim

Similar budgeting challenges were faced by chassidic yeshivos in Poland, who faced fundraising shortfalls during the Great Depression.

Rav Yankele Metz, the Shpieler Rebbe, who resided in the Travys neighborhood of Kielce, Poland, established a yeshivah for the city’s youth in 1925 in order to keep them away from the lure of athletics and sporting activities that were ensnaring many Jewish youngsters at that time. He asked his devoted follower, a tailor, to swiftly traverse Kielce and encourage Jewish boys playing ball to come into the beis medrash. The main attraction of the yeshivah was its maggid shiur, the local dayan, Rav Aaron Shmuel Klobber — about whom the 1929 sefer Maggidei Limud v’Sichah (known by its acronym MLS) writes, “Today, Rav Shmuel is one of the gedolim — a leader of men.”

Rav Aaron Shmuel was ultimately the one who saved the yeshivah from financial collapse when an old friend from his younger years donated an ice pick said to have been used by Rav Aleksander Stichandler — founder of the Shpieler dynasty — to carefully pierce the frozen lake each winter, creating a proper mikveh that met all halachic requirements. The ice pick was then sold to a local financier for a substantial sum — sufficient to sustain the yeshivah for the next decade.

Hungry in Hungary

Hungarian yeshivos during the interwar period faced the opposite difficulty. Due to a surplus of funds among Hungarian Jews, all yeshivos provided amenities for the talmidim in order to attract elite students.

The famous yeshivah in Asachfleish in southern Hungary grew to over 600 talmidim in the last decade before the war, due to its allegedly having the reputation for the best food of any yeshivah in Hungary. Many survivor memoirs describe the food as having gotten better and better over time. One talmid, Elya Tzur, wrote in his bestselling memoir entitled Thank You, Hashem, “The yeshivah promised us constantly that the food will be even better, and even better. Hashem loves us and wants our very best. So the food will always be better.”

Although the yeshivah is no longer with us, a recent episode of the Meaningful Chatter podcast broke the news that the several volumes of the Asachfleisch Yeshivah Torah journal, aptly named Taamei Torah, were recently discovered by the renowned researcher Eli Voosberger-Rosenberg at the Royal Library in Metz. They will soon be republished following a generous

grant from the Schick and Greenwald families.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1053)

Oops! We could not locate your form.