What Lurks Beneath

We like to think our homes are spick-and-span. Well, hygienic at least. but how clean are our homes really?

For as long as there have been houses (and tents?), there have been people trying to keep them clean. In ancient Greece, people cleaned the floors with sand and vinegar, while the ancient Romans used brooms and brushes made from twigs and reeds to sweep up.

There’s no doubt that modern homes are cleaner than their ancient counterparts. We have game-changing technology, such as vacuum cleaners and chemical cleaning products. We’re also much more aware of the relationship between a lack of hygiene and disease.

But I was curious to know just how much cleaner our homes really are. Is it possible that despite our technological advancement and greater awareness of hygiene there are harmful germs lurking about?

I decided to find out.

The Experiment

A small amount of research taught me that you can swab and test for bacteria and other microbes in your own home using a petri dish, sterile swabs, and distilled water. I purchased these items and then set out to find volunteers willing to collect samples from their homes.

When asked, most people said they absolutely wouldn’t want to check their homes for bacteria or any other sort of microbe.

“It’s too triggering for my OCD,” one person told me. “First I’d need to know what ‘normal’ levels are supposed to be. Then I’d spiral, assuming things in my house aren’t normal.”

Another woman told me, “The kitchen is a woman’s kingdom. I don’t need the whole world to know how many subjects I have.”

People admitted they knew every home would yield results, but they seemed afraid their homes would yield something entirely unacceptable. No amount of cajoling would convince them to change their minds.

Some more active searching produced four willing participants: Chavie, Hadassa, Rochel, and Shanie. The common denominator between these women was they were all confident about the way they maintained their homes, but at the same time, none of them categorized themselves as “clean freaks.”

“I feel good when my house is clean and organized,” Chavie said. “Who doesn’t love a clean, organized house?” But she admitted she doesn’t love cleaning and looks at it as something that has to get done.

Hadassa classified her cleanliness level as normal. She said, “I like to be organized. I disinfect counters and phones once a week. I’m not overly crazy about it.”

Rochel wasn’t sure how clean she actually is. “My house is very neat,” she said. “I spot clean whenever I see a mess, and the kitchen floors and bathrooms get a deep cleaning once a week.”

Shanie said that while she’s very particular about some places — her bathrooms get cleaned daily — she’s sure there are places in her home that are neglected. “It’s just not possible that everything is clean all the time.”

They all said curiosity was the driving force behind their willingness to participate in this experiment. Rochel saw another angle, as well. “It’s fun to be part of things with other frum women,” she said. “And people in such a group are always worried that they’ll be the dirtiest one. So I figured I’ll do everyone a favor and I’ll be the dirtiest one, because I have a casual attitude about such things, though I had to keep it a secret from my husband, or risk triggering his germ phobias.”

Game Time

Each volunteer received a few petri dishes and a list of potential spots to swab: doorknobs, phones, makeup brushes, washer, dryer handle, to name a few. After swabbing, they put the dishes in a dark, warm place and waited for results.

It’s important to note that there’s no way this experiment is scientific. Our samples weren’t controlled, and each woman received directions via text. In all likelihood, everyone gathered their samples differently. Also, the conditions under which the samples were incubated varied from home to home.

Still, these women were good sports. They followed the rules. No one swabbed directly after cleaning. In fact, Rochel said she swabbed on a Friday, and her house is cleaned Mondays.

“I did the swabs at a time when things were hectic,” she said. “We were about to leave the house. I quickly rubbed the Q-tip up and down these random spaces and then rubbed them on the petri dish. I didn’t have time to think about cleaning it first. I would say things were about medium-level dirty.”

Shanie said, “My house was clean for Shabbos when I swabbed, so I tried to find places and things that hadn’t been cleaned too recently.”

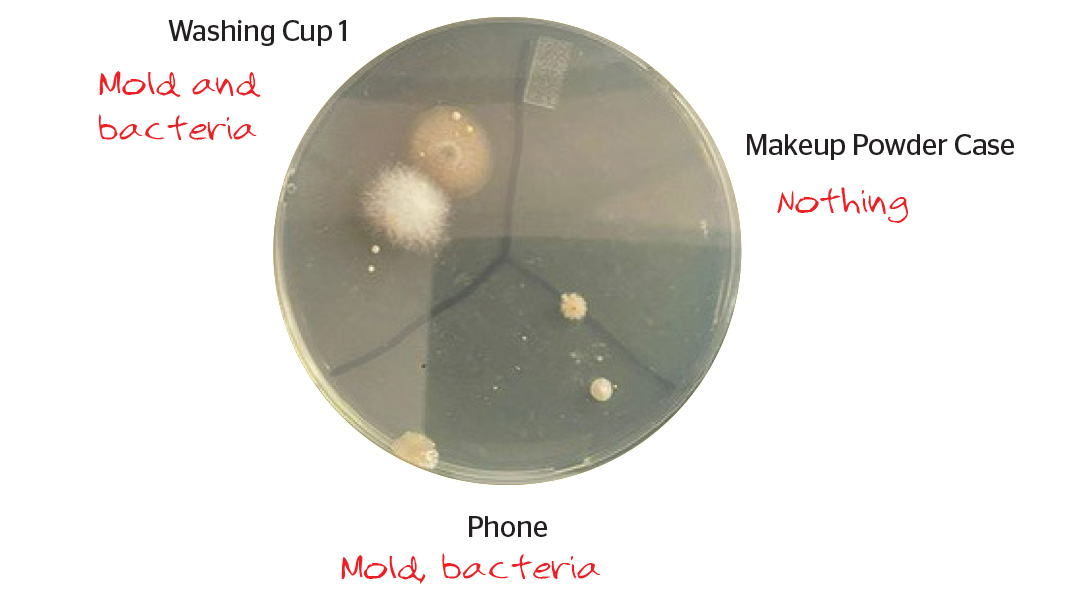

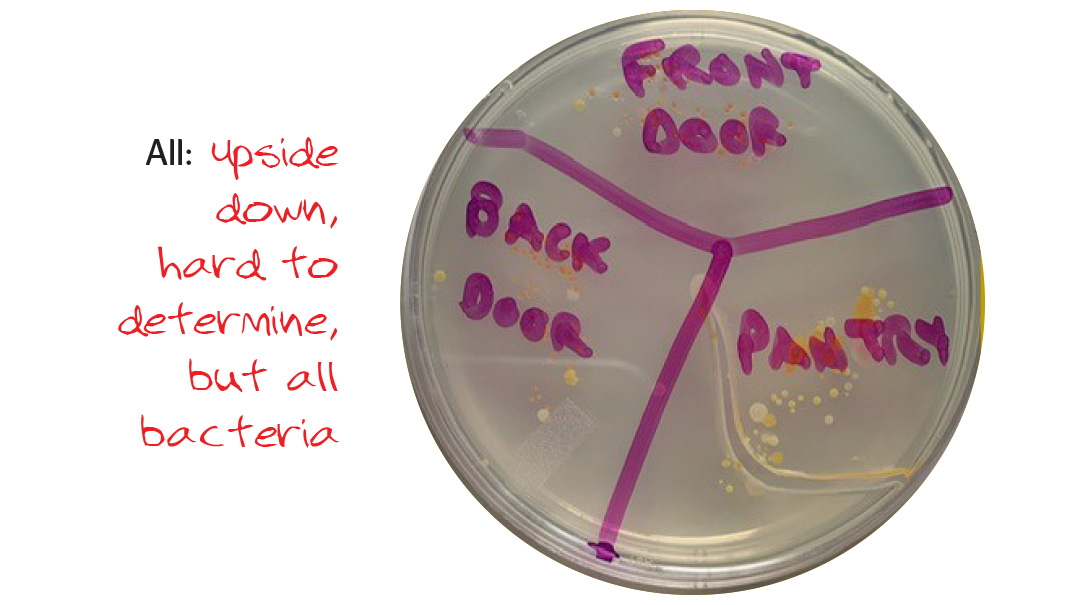

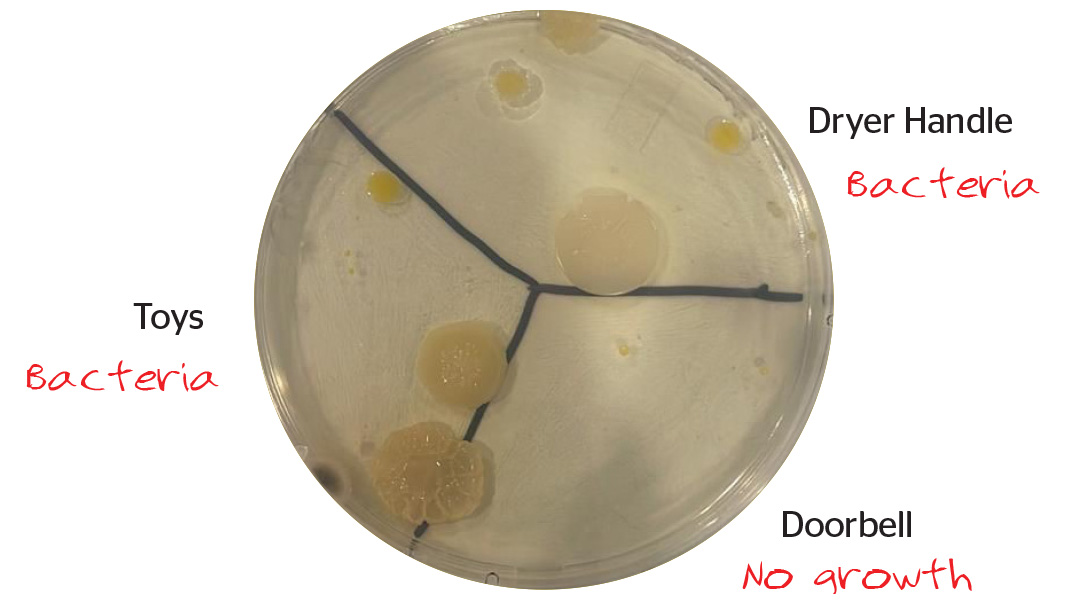

In less than a week, we had results. Chavie, Hadassa, Rochel, and Shanie all sent photos of their petri dishes, and they all showed growth.

What’s in the Dish

To help me make sense of the results, I reached out to microbiologist Jessica Ross Prizont. Jessica lives with her family in South Bend, Indiana. She has a master’s degree in microbiology from Northeastern University and did her clinical research at Tufts Medical School-New England Medical Center. Her subjects: Antibacterial Resistance and Emerging Resistance. She currently teaches courses in biology, physics, and microbiology at the high school and college levels.

The first thing I noticed when talking to Jessica was her easy and ready laugh. She told me she’d have a look at the petri dishes.

After hearing an overview of the experiment, Jessica had questions about the petri dishes we used and the quality of the agar, the gel-like substance at the bottom of the petri dish that helps the bacteria grow. The dishes we used weren’t what she’d have chosen to use, she said. She also expressed concern about the quality of our results, saying that we didn’t have a true scientific control.

I told her our experiment was more curious than academic.

“Definitely not academic,” she agreed, laughing.

I texted her the pictures of the petri dishes and then called her for an assessment. Because she was looking at pictures of samples, and not actual samples, she couldn’t identify them with a hundred percent certainty. She was limited; she could only say what she thought or guessed each sample to be.

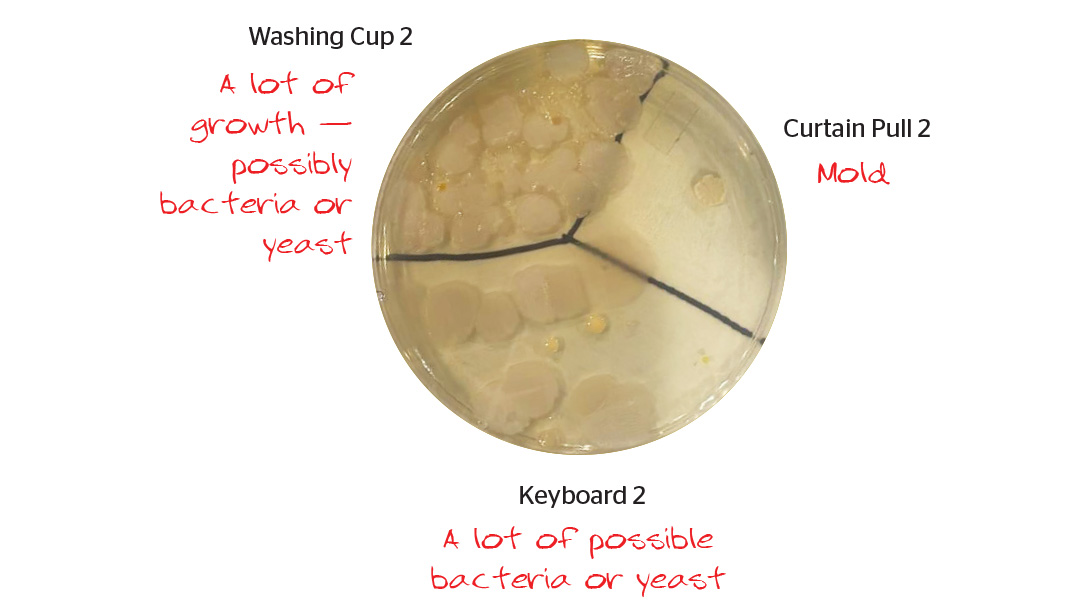

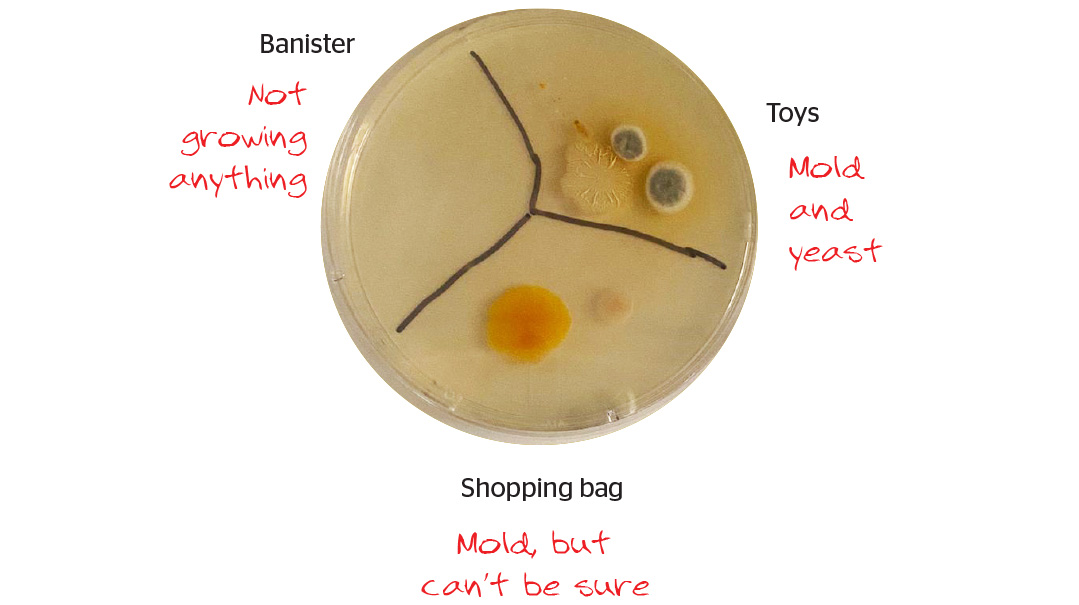

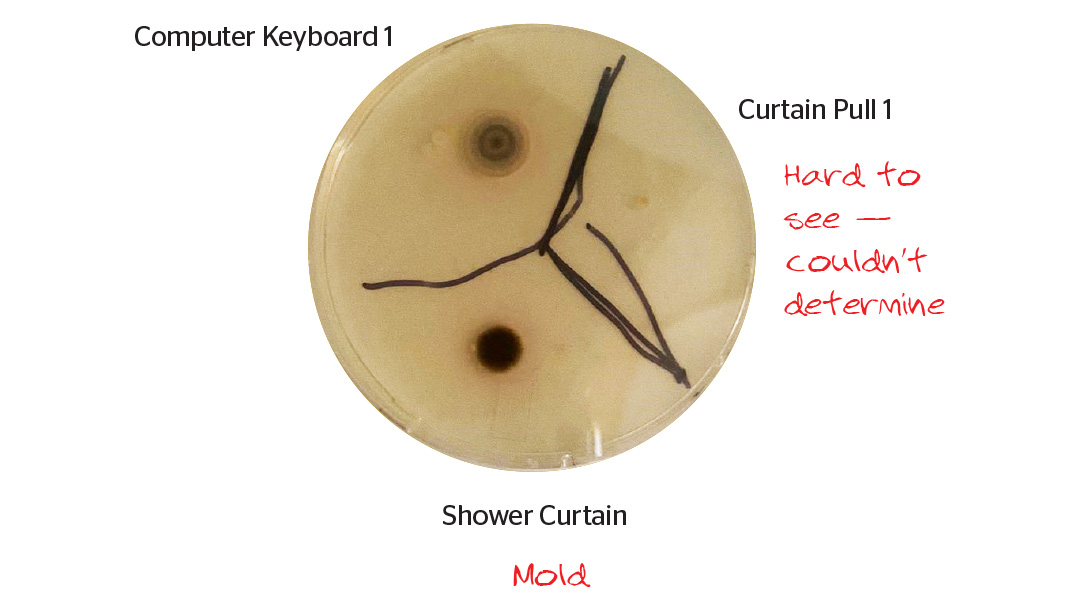

Most of the swabs yielded bacteria, mold, and yeast.

“It mostly looks normal,” Jessica said. “It’s probably not worrisome, but the mold on the washing cup makes me nervous. Mold that is furry has spores and can be dangerous to breathe in.” She suggested checking the cup closely to ascertain mold wasn’t visibly growing. The mold swabbed off the shower curtain and the keyboard could be a potential problem, as well.

“Any time you can actually see mold growing, it means there’s a lot, and you could have a problem,” she says. “Generally, if you see something growing, clean it, because it can be dangerous.”

M

aybe because Jessica is a microbiologist, she ranks places in the home based on their potential bacterial load. The bathroom is a particularly problematic place, she said, and not only because of the potential for mold. In general, there’s a ton of bacteria in the bathroom, something I imagine most people are aware of.

“There are lots of bacteria in the intestines, two to three pounds,” she says. “So your bathroom can be one of the dirtiest places in the house.”

She said she has been in homes where there is no soap in the bathroom. “It’s disturbing,” she said, “but not uncommon.”

Jessica says a place dirtier than the bathroom is the kitchen sink. This is because people are more cognizant of the hazards of the bathroom, and they clean it more often. “There’s a ton of bacteria in food, but people think Oh, it’s food, so it’s not dirty,” Jessica said.

I wondered aloud at what else people aren’t aware of. “Towels,” she said. “The bacteria load in a bath towel after three uses is high enough to warrant washing.”

She said in her own home she’s very careful about the towels people use. If someone is sick, they get their own hand towel. In some homes people will use any towel available, but she has specific towels designated for specific uses and people. If a towel is used by a lot of people, it gets washed. After she has guests, the hand towels get changed.

Jessica washes her hands a lot. After she gets home from work, she said, or after she gets off the subway. Her go-to is regular soap and water. “I don’t use antibacterial soap,” she said. “It can induce resistance. Plain soap and water do the job.”

Yet with all her knowledge and the precautions she takes, she says she’ll eat food that fell on the floor of her home. “I’m not nervous in my house,” she said. “It’s what’s coming from the public space that worries me.”

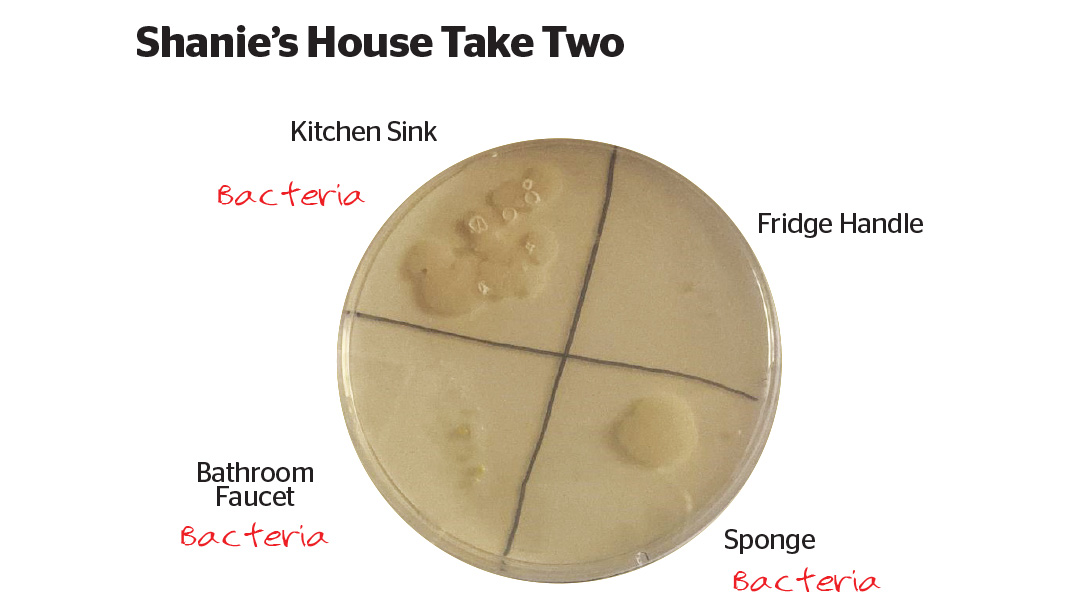

Before our conversation ended, Jessica mentioned that she was surprised we didn’t swab the bathroom. “What places would you have suggested swabbing?” I asked her. “The bathroom faucet,” she said, “the kitchen sink, the refrigerator handle, and a sponge.”

I had one petri dish left. I called Shanie who said she’d be delighted to swab again and collect samples from the places Jessica suggested.

The Outcome

I shared Jessica’s results with everyone. Rochel and Hadassa weren’t particularly worried.

“I don’t feel strongly about bacteria one way or another,” said Rochel. “There are some people who say, Let it grow, it will make your immune system stronger, and some people who say, Get rid of it and you’ll never be sick. I think there’s value to both points of view. I was proud when I swiped certain things, and there was no bacteria, and I didn’t feel worried when I swabbed and bacteria did show up. On the other hand, I didn’t show my husband these things because he’d have a pretty strong reaction to any bacteria. He’s already swamping certain things in Purell, and I don’t want that to escalate. That’s probably why his glasses and the doorknobs didn’t have any bacteria at all.”

Rochel doesn’t plan to do anything differently.

Obviously, there’s bacteria in the house, Hadassa told me. There’s bacteria all over, she says. “I expected to find it,” she said. “But I thought that was normal.” She doesn’t plan to change her cleaning routine.

Chavie sees it differently. “Seeing the bacteria makes me want to sterilize my house,” she said. “I’m extremely clean, but there’s always room for improvement.” She already bleaches her bathrooms twice a week, but she plans to pay closer attention to her dishwashers and her laundry room — areas she says are prone to mold.

Meanwhile, Shanie swabbed the refrigerator handle, the kitchen sink, a sponge, and a bathroom faucet. All, aside from the refrigerator handle, showed a ton of bacterial growth.

Shanie said she feels disappointed there was so much bacterial growth, because she always thought of herself as someone who keeps things very clean, but there’s a bright side to it too. “We’ll just focus on those places more often and more diligently.”

Should you wear shoes at home?

Often, people whose household rules include a no-shoes-in-the-home policy are viewed as finicky and fussy, but studies show they may be onto something important. According to a recent study conducted by a group of environmental scientists, a third of the dirt buildup inside your home comes from outside, much of it tracked in via the soles of our shoes.

While not all dirt is bad dirt, much of the dirt they studied included “a high prevalence of microbiological pathogens.” Shoes come into contact with various surfaces such as sidewalks, streets, public restrooms, parks, and other areas that can be contaminated with dirt, debris, pesticides, chemicals, and even harmful bacteria. When you wear shoes indoors, you can transfer these contaminants onto your floors, carpets, and other surfaces. Bacteria such as E. coli, Salmonella, and other pathogens can hitch a ride on the soles of your shoes and be deposited throughout your home. This can pose a potential risk to your health, especially if you have infants, young children, or individuals with weakened immune systems in the household.

Additionally, shoes can also bring in allergens like pollen, mold spores, and pet dander, which can exacerbate allergies and respiratory issues for sensitive individuals.

Try This at Home

In order to replicate this experiment, you’ll need the following supplies:

- Petri Dishes — I used one from Amazon.com

- Distilled water (available at Target)

- Sterile cotton swabs

Instructions:

You can divide your petri dish into sections using a permanent marker on the underside of the plate. Do not write on the agar.

Choose a place to swab, and label the section on the petri dish so that you know what you swabbed.

In order to swab, wet sterile swab slightly with distilled water to lift the sample. Rub the swab on the petri dish from side to side within the section you allotted.

Put the petri dish in a dark, warm place. You may see some growth after 72 hours. DO NOT OPEN THE PLATE.

Discard after a week by placing the used petri dish into a sealed Ziploc bag.

Dirty places you may not have thought to clean and how to clean them

Coffee Machine

Mold, yeast, other bacteria, oily residue, and hard water deposits can build up inside the reservoir and pot. To deep clean your coffee maker, fill the reservoir with a 50-50 solution of distilled white vinegar and water. Run a brewing cycle without any beans, stopping about halfway through to let the vinegar solution soak for at least 30 minutes. Finish the cycle, then repeat with clean water to flush away any lingering vinegar scent.

Washing Machine

Wet laundry left in the machine, even for short periods of time, can cause germs to flourish, and dirty laundry can fill your washing machine — and future loads of laundry — with bacteria and viruses. To keep it fresh, run your washer empty with a cup of bleach once a week.

Knobs, Handles, and Switches

High contact places accumulate bacteria and germs. Clean bathroom light switches, refrigerator handles, stove knobs, and microwave handles once a week.

Makeup Bag

Over time, makeup bags can accumulate makeup residue, oils from the skin, dirt, and bacteria or other microbes. Clean your makeup brushes, sponges, and other tools regularly to prevent product buildup and transfer of bacteria into the bag. Periodically go through your makeup collection and discard any expired or old products. Expired makeup can harbor bacteria which can cause skin and eye infections.

Workstation

Remote controls, tablets, computer keyboards and phones are all high-touch surfaces that can accumulate germs. Wipe down each one every few days.

Faucets

You likely wipe down your faucets regularly, but you also need to consider the aerator — the part of the faucet where the water comes out. Mildew can accumulate in there. Every few months, remove your faucet aerator and soak it in vinegar for 15 minutes.

(Sources: Healthline, Better Home and Gardens)

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 846)

Oops! We could not locate your form.