We’re Only Addressing Half the Problem

| February 17, 2021The Jewish community can do better. It must do better. The effects of domestic abuse, whether the victim is a woman or a man, can be catastrophic

Shimi’s marriage of ten years had been rocky for some time. Demeaning comments from Dinah — about his physical appearance, his paycheck, or his parenting style, often within the kids’ earshot — were regular occurrences. Shimi also had fewer and fewer friends, as Dinah seemed to find faults in anyone he was becoming friendly with in shul. Shimi knew he wasn’t perfect — he would often get angry and scream at Dinah or the kids — but despite all his work to be calmer at home, the tension with Dinah was not improving.

“I think we need some space to work on things from a distance,” Dinah told Shimi one night before they went to sleep.

Desperate for this last-ditch chance to save their marriage, Shimi reluctantly agreed, and in the next few weeks, Dinah moved with their children to her parents’ home out of state. Then, one day, to Shimi’s surprise, the phone call came.

“I’ve filed for divorce,” Dinah told him flatly.

In a daze, he called a divorce lawyer to discuss the upcoming process and custody of the children.

“How long have the kids been living out of state?” the lawyer asked.

“Well, looking at the calendar, it’s been just over six months,” Shimi replied.

The lawyer’s tone changed. “This is going to be an uphill battle. In Dinah’s parents’ home state, six months establishes residency, which means your kids are legal residents of her parents’ state, and the courts in that state have jurisdiction over custody proceedings. Ultimately, it may mean that you cannot take the kids out of that state without Dinah’s consent.”

In the ensuing months, Shimi suffered terribly, feeling lonely, betrayed, anxious, powerless, and guilty. He realized that he badly needed support. And that’s when he began to wonder: “Where can I turn to for help?”

The unfortunate reality is that presently, Shimi and those facing similar circumstances have few communal options. To understand what could be done differently, we should consider how we got to this point. In the early 1990s, the belief that domestic abuse does not happen in our communities began to crumble. Medical professionals, lay leaders, rabbis, and rebbetzins began speaking about the fact that women in Orthodox Jewish communities had been victims of domestic abuse, and in 1992 the Shalom Task Force began.

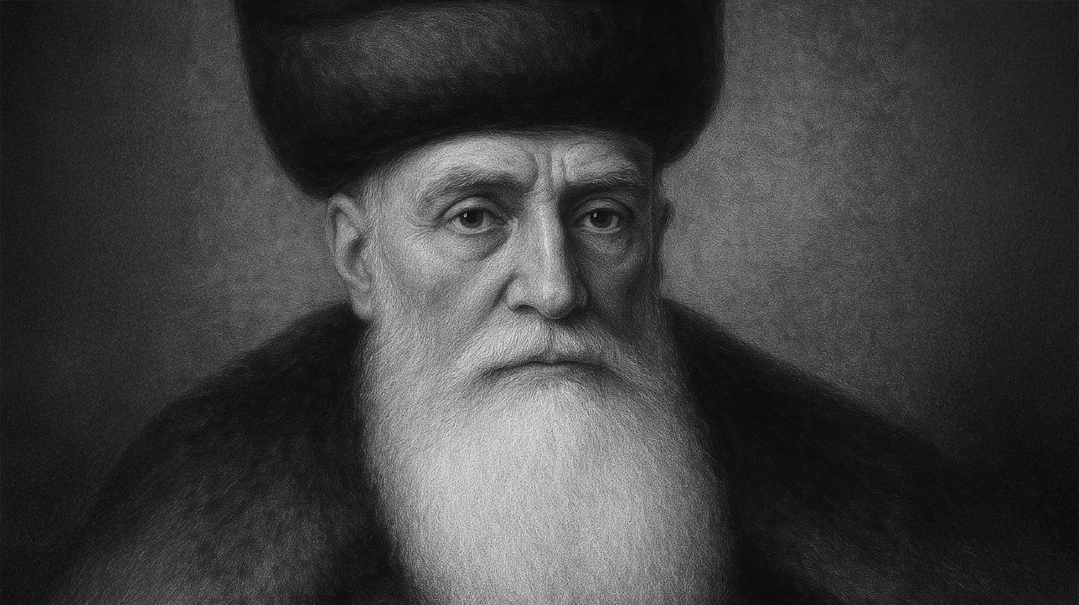

Then, in 1996, Rabbi Dr. Abraham Twerski published The Shame Borne in Silence: Spouse Abuse in the Jewish Community. To the great credit of these awareness-raising pioneers, for nearly 30 years since then, Jewish communities around the world have founded and sustained many organizations aimed at education, prevention, and support of victims of domestic abuse.

Intervention was focused almost entirely on female victims and male perpetrators, which was reflected in the resource allocation, educational programming, and training materials of domestic abuse support organizations around the world. This belief was consistent with secular literature at the time, which understood that men received implicit and explicit messages of patriarchal dominance over women, and as the theory goes, men who perceive that their sense of authority is threatened will assert their control through violence. Compounding the problem, advocates highlighted characteristics of the Jewish community that were assumed to be especially problematic in this regard.

However, these assumptions, by and large, have turned out not to be supported by empirical evidence.

The first assumption about abuse in the Jewish community was that the abuse ran in only one direction, and female perpetrators and male victims of domestic abuse were virtually nonexistent. Prominent Jewish writers, echoed by many others in the field, asserted that 95 percent of victims of physical abuse in a marriage are women and only 5 percent are men — a 16:1 ratio.

However, this belief turned out not to be substantiated, as study after study has shown that women are perpetrators of domestic abuse at rates comparable to men. Furthermore, the belief that patriarchal views explained most instances of domestic abuse turned out to be false. Many of the most rigorous studies suggest that other factors, such as individual personality characteristics, impulse control, and life stressors have much more to do with domestic violence than do patriarchal beliefs of men in society.

Evidence suggests that the percentage breakdowns of females and males injured through physical aggression are closer to 60-40 or 70-30, not 95-5. For example, the most recent statistics available for the United States saw 2,237 people killed in incidents categorized as domestic violence, with 68 percent of the victims being women. This ratio is roughly 2:1, indicating that women are victims of severe physical violence far more often than men, but nowhere near the 16:1 ratio that had been assumed among advocates in the Jewish community.

A second assumption was that other types of abuse that may be more common when perpetrated by women — emotional, verbal, financial — are not as serious as physical abuse. Understandably, physical abuse has received much more attention in the research, as the need to protect a victim from immediate bodily harm is more urgent than intervening in other forms of abuse.

Nevertheless, the existing studies on emotional abuse have demonstrated that a history of experiencing emotional abuse in an intimate relationship is strongly correlated to suicidality, substance abuse, and depression — at rates similar to a history of experiencing physical abuse. Consider the recently reported statistic that an average of 285 divorced or divorcing men die by suicide each year in Israel. As a clinical psychologist, I (Rabbi Dr. Eisen) have seen the detrimental effects that emotional abuse can have on men. They experience despair and hopelessness, as they face ex-spouses and a system that seem aligned to crush them financially, as well as limit access to their children.

There is also evidence that emotional abuse tends to be perpetrated by both men and women at similar rates. Take, for example, the painful reality of get refusal, which is a vicious form of emotional abuse against a spouse. According to 2017 data from the Israeli Rabbinate, of the 809 cases of get refusal, 382 of the refusers were men compared to 427 women refusers. Notably, despite that disparity, 69 male get refusers were incarcerated for their refusal, compared to zero women.

Although Jewish communities have seen some progress over the past decade in supporting male victims of domestic abuse, both academic study and community activism continue to provide implicit messages that male victims are a small minority and not an important area of focus. So, we wondered, what would the data say?

Lamdenu–Zichron Nachum v’Sarah, an organization devoted to addressing core communal concerns in the Jewish community, conducted an online survey of frum divorced singles asking a range of questions, including some related to various types of abuse during marriage. The survey received 214 responses, 61 percent of whom were women. Over 97 percent of responders identified as Orthodox Jewish at the time of their marriage, and marriages lasted an average of 11.5 years (median nine years).

Of the women who participated in the study, 67 percent reported being the victim of verbal abuse, compared to 65 percent of men. Additionally, 16 percent of the women reported being the victims of physical abuse, compared with 22 percent of men. The simple presentation of the most basic numbers tells a remarkable story that many readers may find difficult to believe. Divorced men, in numbers comparable to divorced women, report being victims of both verbal and physical abuse in their marriages.

Of note, we do not know about the severity or duration of abuse, which may differ between genders, and may have relevance to both the short-term and long-term impact of the abuse. However, despite these significant unknowns, the findings are, at the very least, a clear indication that the phenomenon of men as victims of domestic abuse demands far greater attention than it has been given to date.

What can the community do?

Just as it took too many years for us to recognize that domestic abuse toward women occurs in our communities, it has taken far too long for us to accept the reality that men are also often victims of domestic abuse. There are a number of steps the community needs to take.

First, we need a robust, scientific, unbiased effort to fully understand the phenomenon of domestic abuse. The lack of empirical information to date has led to less effective, and at times even harmful, interventions and community activism.

Second, organizations that provide advocacy and support in cases of domestic abuse — as well as those involved in related issues like agunah challenges — need to recalibrate their programming to reflect the reality that there are likely as many men suffering from domestic abuse, in one form or another, as there are women. Organizations also need to ensure that their services are not weaponized — whether by men or women — as tools of emotional abuse.

Third, communities need to establish support networks for divorcing men, particularly those with children, to provide education and support regarding their needs and rights. Such organizations already exist to support women, like Sister to Sister, yet we are not aware of any robust, comprehensive efforts to support men going through divorce.

In our opening story, Shimi was the victim of emotional abuse. Dinah, over the course of years, had denigrated him and isolated him from a network of potential friends. Finally, in divorce, Dinah manipulated the system to create a circumstance of severe parental alienation, which is a form of both spousal abuse and child abuse. Perhaps the challenge is most clearly described by researchers examining characteristics of male callers to domestic abuse hotlines (Hines 2007):

Overall, the male victims of severe intimate partner violence (IPV) in many ways resemble female victims of severe IPV in that they experience similar controlling and physically abusive behaviors from their spouses, but in many ways, they have experiences that are unique to male victims, such as their experiences with a system that is designed to help female victims of IPV.

For too long the Jewish community has denied the painful reality of male domestic abuse victims and the catastrophic outcomes — for the men as well as their children — that the abuse inflicts. Unfortunately, some men turn to alcohol or substance abuse. Some struggle with suicidality. These maladaptive responses to their anguish tend to feed negative stigmas that our society has toward men, who instead deserve compassion as victims of domestic abuse.

The painful truth is that in many cases, these are coping mechanisms, unhealthy as they may be, to survive the day-in-day-out abuse that they suffer within their marriages and divorces. Many also assume that if a woman has inflicted abuse on her husband, it must have been in self-defense from abuse that he perpetrated toward her or the children. What the general data show, however, and what our data seem to confirm, is that male victims are not rare, and they deserve help and support no less than women victims.

The Jewish community can do better. It must do better. The effects of domestic abuse, whether the victim is a woman or a man, can be catastrophic, and ignoring this reality costs families and communities dearly. Over the past 30 years, the Jewish community has done an incredible job of addressing half of this problem. The time has come to stop ignoring the other half.

Rabbi Dr. Ethan Eisen is a licensed clinical psychologist in Ramat Beit Shemesh, Israel. He is the author of the newly published book, Talmud on the Mind, and serves as a research consultant for Lamdenu–Zichron Nachum v’Sarah.

Rabbi Yehoshua Berman is a lecturer and writer in Ramat Beit Shemesh, Israel, founding director of Lamdenu–Zichron Nachum v’Sarah, and author of Reflections on the Parsha, A Malach in Our Midst, 101 Engaging Questions, and Pictorial Parsha.

Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 849.

Oops! We could not locate your form.