Could the 30 million Igbos who populate the country really have their roots in the lost tribe of Gad? We headed off to the Dark Continent to see for ourselves

T

he scene was surreal. We were sitting in Port Harcourt Nigeria in a torrential equatorial downpour. Within minutes the dirt courtyard became a swamp and the roads were ankle-deep in water. The clouds were so thick that the sky turned the color of post-shkiah before Shabbos ends. But the rain and mud didn’t seem to distract the boys who crowded around us many with peyos braided out of their afros.

They peppered us with questions in halachah and philosophy all of this after an hour-long Shacharis recited in near-flawless Hebrew with leining from a paper Torah scroll. Their skin is the rich dark black of West Africans and they are not considered halachically Jewish but in all of our travels we’ve yet to find such a dynamic and serious group of people looking for the truth and learning Torah. We have been to some of the world’s most unusual and remote emerging Jewish-identifying communities but nothing prepared us for what we found in Nigeria.

Lost Tradition

It’s a huge country the most populous in Africa with over 180 million people and the world’s 20th-largest economy. Despite being rich in minerals and being awash with oil and natural gas (gasoline at the pump is cheap) most of its people are extremely poor. Only half the population has access to potable water and life expectancy is just 53 years. The infrastructure is in terrible shape — the roads are full of huge potholes that can overturn a truck and the electricity supply is wholly unreliable.

The house in Ogidi in Anambra province where we stayed on Shabbos was not a pauper’s dwelling and yet it receives electricity from the grid for only a few hours a day. Our hosts like millions of others in the country have a small private generator (which they thankfully kept running all of Shabbos especially for us) and we were grateful for that because it meant we had a fan to keep us cool at night in the sweltering heat. (In a huge supermarket in a big city the power just stopped for no apparent reason and the same thing happened in the international airport.)

Nigeria is roughly half Christian and half Muslim. (The local fundamentalist Islamic terror group Boko Haram regularly makes headlines by committing indiscriminate bombings and kidnappings.) But the Christian millions are actually newcomers to that religion. Prior to their exposure to Christianity by missionaries in the 17th through 19th centuries they practiced an assortment of local religions — and many it seems even practiced some Jewish rituals.

Letters by missionaries sent back to Portugal four centuries ago claim discovery of a tribe that had Jewish customs. Those letters were surely referring to members of the 30-million-strong Igbo ethnic group whose own tradition traces them back to some of the Ten Lost Tribes.

The memory of the devastating 1967–1970 Biafra War in which the Igbo fought for freedom — and which saw as many as 3 million people killed by starvation, shootings, and bombings — still casts a shadow over the country. It was during that period that Israel began forging a relationship with the Nigerian government and also developed a bond with the Igbos, based on shared traditions.

It’s believed that today, some 30,000 Igbos practice some form of Judaism, although the number practicing normative Orthodox Judaism is said to be between 1,500 and 2,000. The rest still adhere to Christian doctrine as well.

These Igbo “Jews” believe that they derive from Eri, the fifth son of Gad ben Yaakov Avinu (Bereishis 46:16). In fact, the kings of the Igbo have a family tree attesting to this, and today they even call themselves the Eri or Umu-eri.

Some Igbos claim their ancestors migrated from Syria, Portugal, and Libya into West Africa in the 8th century, the initial immigrants speculated by some to be from the tribes of Gad, Asher, Dan, and Naftali. Some of them speculate that their name — Igbo — is derived from a mistaken pronunciation of “Ivri” by the locals when they arrived in West Africa, but over the centuries of wars and disasters, the Igbos allegedly lost whatever written documents and traditions that may have existed.

Even with the loss of written records, many religious practices of the Igbo “Jews” correspond with Jewish practices, including circumcision on the eighth day after birth, observance of certain kashrus laws, a version of family purity, and the celebration of some festivals.

While the overwhelming majority of the Igbo live as Christians, they are aware of a “Jewish heritage.” As we rode in a taxi in the city of Enugu, the driver asked where we were from, and when we told him Israel, he asked if we were Jewish. When we said yes, he responded that he was an Igbo, and all Igbo are descended from Jews. He admitted that although most Igbo today are Christian, they have a long tradition that their ancestors were Jewish.

When we asked our driver how the Igbo differed from other Nigerian tribes, he sounded like the stereotypical Jewish mother: “The Igbo are more intelligent and more creative, and if they gave the oil-producing region to the Igbo, within a few years we’d have another Japan.”

The Return

In the last 40 years, tens of thousands of Igbo have begun questioning their Christian beliefs and have begun to declare their love of Judaism and their desire to “return to their roots.” A sizable minority of the Igbos are Sabbatarians — they refrain from work from Friday night until Saturday night and wear white all Shabbos, but in all other regards are still Christian. And then there are several thousand who are actually living as Jews.

This return is staggering. There are currently over 60 “synagogues” in Nigeria. Our own trip was facilitated by two Torah-observant men from Israel who have decided to help them, which also has great political implications for the State of Israel. For example, in a 2014 vote on Palestinian statehood in the UN Security Council, Bibi Netanyahu convinced the Nigerian president to abstain. The Nigerian delegate cast the deciding vote in preventing the motion from passing.

We were happy to be traveling with two world experts on the Jewish Igbo. The first, Dani Limor, is an energetic, affable, unflappable man whose life has been one long service to the Jewish People. He attended Yeshivat Kerem B’Yavneh before his army service, where he eventually rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel and fought in the Six Day War, the Yom Kippur War, and the First Lebanon War. In the fighting, his armored troop carrier took a direct hit, and everything on the side of the attack was burned to a crisp, except his tefillin, which remained unscathed.

Much of what Dani did afterward is classified, but was of enough significance to the state that he often reported directly to the prime minister. His longest and most well-known declassified mission was his four-year stint as commander of the clandestine operation to rescue Ethiopian Jews from the deserts of Sudan. He has been deeply involved with the Igbo Jews for the past six years and was our trip coordinator.

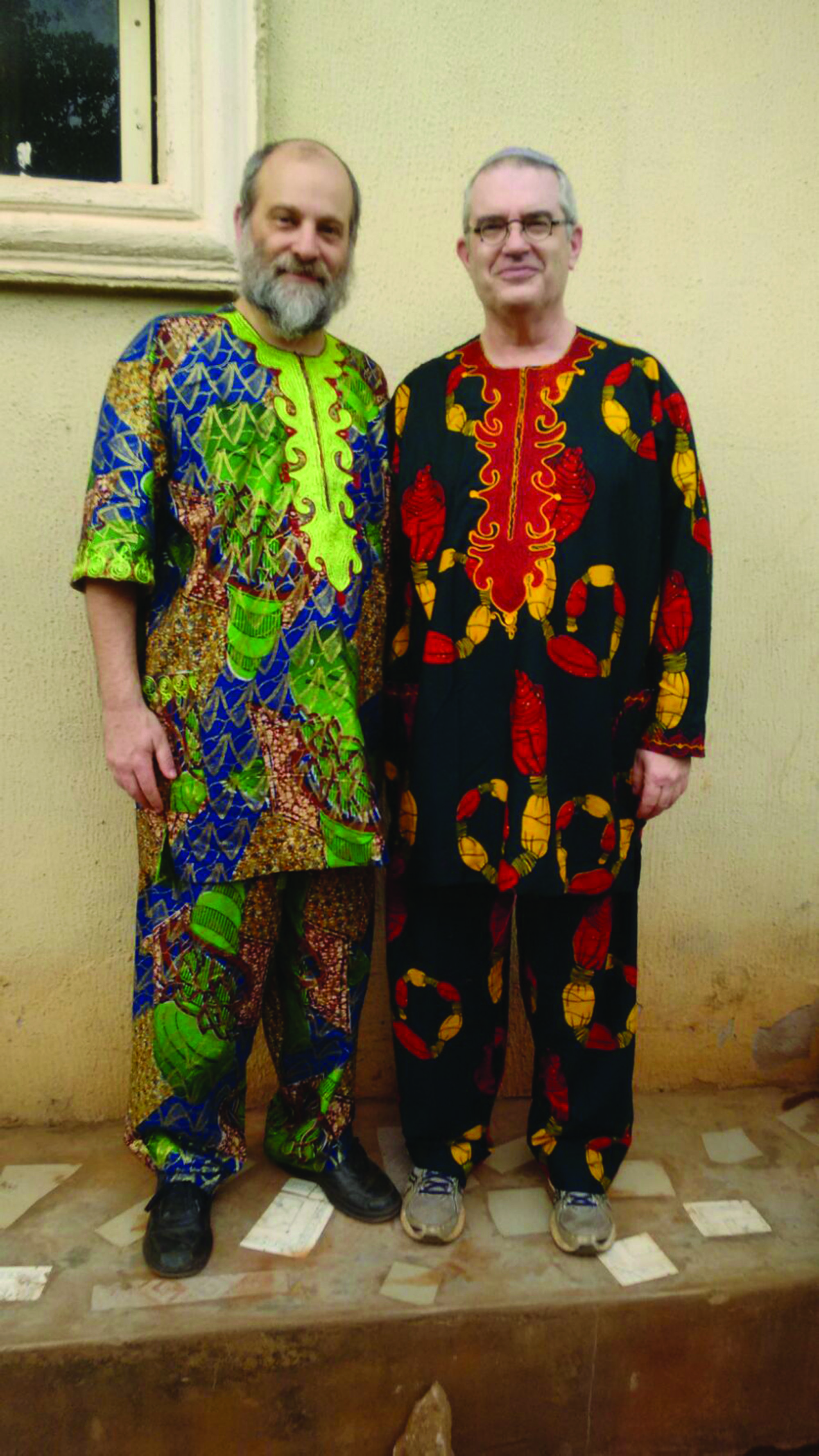

The other, Gadi Bently, is a young yeshivah and university student who is good friends with Dani’s son. When Dani was looking for a young, enthusiastic, yeshivah-educated person to go teach those in Nigeria who are truly committed to authentic Judaism, Gadi was a natural choice. This was Gadi’s fourth trip, and the youth flock to him — they are the ones spearheading the movement to learn Torah and practice normative Judaism.

Fishy Business

In our journeys, we’ve often run into the halachic problem of teaching Torah to those who are not actually Jewish. As in the past, we consulted with rabbinic authorities in order to delineate the exact parameters of what is permitted.

We were in Nigeria to teach, and wound up fielding an assortment of questions that surprised us. Despite their not being halachically Jewish, the Igbo Jews perceive themselves as such. Here we were, sitting around a dirt courtyard outside the Igbo Jewish Community Synagogue with chickens clucking and Israeli and Nigerian flags flying on the gate. Banana and coconut trees surrounded us and a group of 30 native Nigerians, who have been practicing Judaism for a few years, enveloped us.

One woman wanted to know: Her husband threw her out of the house and wouldn’t give her a get. How should she proceed? (We gently told the woman that since she never had a Jewish wedding, and is not halachically Jewish, she actually did not need a Jewish divorce.)

In a visit to the village of Obulafo in the Nsukka district, we found ourselves in the middle of a milchamta shel Torah without realizing it. A big machlokes was raging in the stifling hot village. They wanted to know if a fish they call mackerel is kosher. We explained that the name is not sufficient to determine if it’s kosher. So in this village with no electricity or running water, a bunch of guys take out their smartphones to show us assorted pictures of the fish. Despite the pictures clearly showing some sort of scales, we explained that one needed to actually examine the fish and verify that it had macroscopic scales that could be peeled, in order to pronounce it kosher.

Well, before we knew it, a fresh fish was sitting in front of us. On initial examination, it looked like it had many tiny scales, but they did not seem to peel off. However, we persisted and checked around the neck, and indeed, we were able to easily remove several small, regular scales.

When we declared the fish kosher, pandemonium erupted and the two warring sides started yelling at each other. It seems that when these people took Judaism upon themselves and stopped eating meat, the status of every available fish became important — and there had been heated debates about this one.

We were discussing a particular halachah when some fellow stood up and said, “But the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch disagrees.” When discussing what’s involved with keeping kosher, a man raised his hand and asked, “Is that l’chatchilah or bedieved?” They asked about the status of food stored under a bed and about water left uncovered.

Halachos that have little relevance in our processed world were actually quite relevant to them. The Shulchan Aruch (Yoreh Deiah 81:8) says that honey is permitted even if some bee parts are mixed in to it. Such honey does not exist in our stores, but it does here — and one man asked about it. At one point we even found ourselves discussing Parah Adumah, and were shocked to hear them respond knowledgeably about levels of tumah.

Despite the lack of running water, every synagogue we visited had a large barrel of water and a washing cup outside the main entrance to enable a proper washing of the hands before entering.

Local culture obviously impacts on their worldview. While not common in the southern part of Nigeria where we were, polygamy is legal in the Muslim north — although one of the leaders of the community asked us for the Jewish position on the matter.

After we presented the history, halachah, and current state of affairs, an elder with a limp and a cane who had been a commander in the Biafra War stood and blurted out, “But what about Isaiah 4:1?” and then proceeded to quote how “and in that day, seven women will take hold of one man saying, ‘We will eat our own bread and wear our own clothing, only let us be called by your name, take away our reproach.’ ” In other words, wouldn’t a woman prefer to be a co-wife than remain alone? [The Gemara discusses it as well, but Rav Moshe Feinstein (Igros Moshe Even Ha’ezer 4:83) and others consider this mindset to be possibly subject to societal forces.]

Their devotion is remarkable, considering that even in their ancient tradition, there was no development of Oral Law. But that hasn’t stopped them from learning contemporary halachah, which is what they’ve been taught over the last few years: One teen, for example, goes to a private school where a very short haircut is obligatory every two weeks. During Sefirah he refused to cut his hair and was beaten by the teacher. And when embarking on one of the long rides between towns, we piled into a van and before we realized what was happening, one of them had begun to recite Tefillas Haderech.

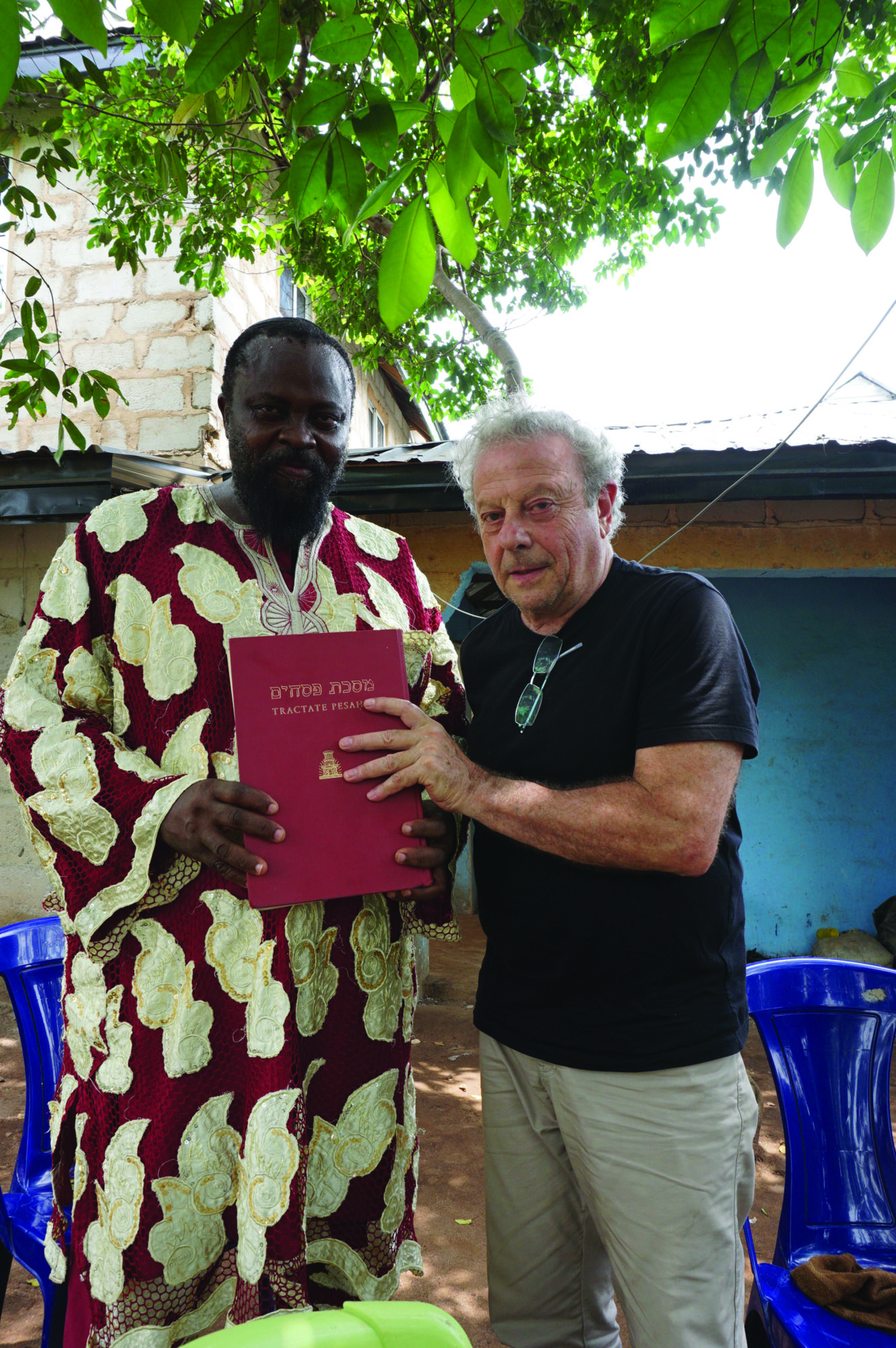

Still, they have very few Jewish books, and they value every one they can get their hands on. One of the few books they have is the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch, and they’ve photocopied it together with the siddur, which they’ve distributed to the various communities. We traveled to a small synagogue in the middle of the fields where one of the first men to get involved in Judaism 30 years ago lives. He once told Dani that he wanted to learn Gemara, so we brought him the prize of his life: an old Soncino English translation of Maseches Pesachim.

We wish we could share the davening with you. Every single word, recited out loud by all of them, was clear and crisp. They know many of our tunes, and in fact we heard Avraham Fried blaring from the courtyard on Erev Shabbos. But they’ve also integrated many of their Nigerian tunes into the niggunim they sing — unusual melodies and harmonies, with a beat very different from ours.

Wherever we went, people begged us to visit them. One of those people was Hadassah, the leader of a large community in Owerri. Hadassah told us she has 500 people participating in Shabbos services and that she runs one of two Jewish schools in the country — not an afternoon Talmud Torah, but a proper school with Jewish and secular studies recognized by the ministry of education. As we were only an hour away, we agreed to come for a 15-minute visit.

It had rained and lakes of muddy water filled the cratered streets. This was the worst area we had yet seen. Garbage thrown everywhere, crumbling buildings, and a sense of decay was palpable. Yet as we approached the gates of the blue-and-white compound, we heard a cacophony of noise and singing. Welcoming us were 250 adults along with the schoolchildren. The little kids sang the alef-beis and the high school kids ended our visit with “Hatikvah.”

Then Hadassah handed us a fancy gold embroidered tunic and a red cap. “This is the costume of a chief,” she said. “We now make you an official Igbo chief.” We walked back to our car, followed by a hundred men singing “Am Yisrael Chai” and waving Israeli flags.

Love That Kosher Wine

The Nigerian diet is limited to a lot of rice, noodles, and fish. Some things are nearly universal, and in the Third World, bananas, with their thick peel, ubiquity, taste, and nutritive value, are a staple.

In Uganda we were introduced to the cassava (yucca root); and in Nigeria we met a bitter nut called the cola nut. When a guest arrives, the Igbo have a formal custom that the host brings out a plate full of cola nuts. The guest is expected to take one, bless the host in the native language, and then eat the raw, bitter nut. Not doing so is considered an insult. The first time we had to do it, we made the brachos of ha’eitz and a shehechiyanu and took a bite — having second thoughts about whether such an awful-tasting nut warrants a shehechiyanu!

Often when we travel and know we’ll be off the beaten track for Shabbos, we bring along kosher wine, one of the more difficult items to find outside of established Jewish communities. This trip was no exception. Nigeria is certainly not known for its Jewish communities, and we wondered how they usually make do.

Boy, were we in for a surprise when they told us they have imported kosher wine — Manischewitz is available in all big supermarkets because the local Sabbatarians use it. Sort of brings us back to postwar America, when Manischewitz was the leading kosher wine, yet its main market was black Americans. Manischewitz sales records from the 1950s show the expected upsurge at Pesach, but surprisingly, the sales at Christmas and Thanksgiving were several times higher than those at Pesach. By 1973 about 85 percent of its magazine advertising budget was being spent on ads in Ebony magazine. It seems that the taste of Manischewitz is enjoyed by both black Americans and Nigerians.

The King and I

On Friday morning, we were invited to meet the king of the local Igbo. Arriving at his palace complex in Aguleri, where the Nigerian, Igbo, and Israeli flags were flying, we were brought to the throne room to await his entrance. It was resplendent, with a lion-skin throne and a life-size stuffed leopard with his teeth bared standing next to an ivory scepter. Pictures of the king and his coronation 40 years earlier adorned the walls. What surprised us the most were the numerous pictures that included rabbis and religious Jews. There was even one of the king wearing a tallis!

His majesty entered wearing flowing robes, a Magen David, and a cloth crown on his head. He talked about how he perceived our kinship, and about the State of Israel. On a previous visit, when Dani noticed a lion and Magen David on the Igbo king’s clothing, he inquired about them. After all, their tradition is that they are descended from the tribe of Gad, and Gad is not known to have a lion as its symbol. The king answered that there is a Biblical account in which his ancestors, the tribe of Gad, who inherited the land on the east bank of the Jordan, at one point crossed over to the west bank for protection that was offered by the tribe of Yehudah — and hence the king wears the symbol of Yehudah. (That may be a stretched interpretation of Divrei Hayamim, chapter 15.)

Dani, who has been here many times, had been crowned a chief a few years ago, and the king wanted him to join him this year when the cabinet met. He told us that he was going to see the governor of the state at his residence in Awka, and he would like us to come with him. We thought it was to be an intimate affair, never imagining what awaited us. The event was not a small informal meeting; hundreds of the most influential kings, chiefs, and religious leaders of the state were gathered for the third anniversary of the governor’s term, and they were preparing to listen to a lecture by a renowned Nigerian economics professor.

The huge tent set up for the affair held 500 people, and anybody with power or wealth was in attendance. The king waltzed us past security into a room of sharply dressed people in a country where many have just a few changes of clothing. As people noticed our yarmulkes, many stuck out a hand to shake and said “shalom.”

As the king ushered us up to the front to meet the governor, we passed several tables of kings of different tribes, dressed splendidly with crowns on their heads. We met the governor, as well as another Igbo leader proudly wearing a yarmulke.

Then came the real shocker. The professor got up to speak and in his first few words, he recommended a book for all the leaders to read. The name was Start-Up Nation, the international best-seller on why Israel is a powerhouse on the international stage in high-tech start-ups, and how they as a nation have a lot to learn from the Jewish state.

A Little Palm Grease?

In some countries it’s called baksheesh. In the West we might call it a bribe. In Nigeria it is just the way you do business and it is everywhere, from the bottom of the economic ladder to the very top. At one airport, a border control agent said to the person in front of us, “Did you bring anything for your friends in Enugu?” When the visitor slipped her a $10 bill, she made it clear that another $10 would get them through immigration uneventfully.

At a different airport, the security inspector asked the people in front of us if they had anything to declare, and when they obliged with a “tip,” they were waved on. Highway patrolmen are improving their living that way, while raising nothing for state coffers. A study released while we were there found that extortion by various traffic officials costs the state about 27 billion Nigerian naira (about $86 million).

By the same token, while leaving the country, we went through a contraband check where we were expecting to be asked for a “present.” Instead, our yarmulkes, our smiles, and saying “thank you” in Igbo elicited enough goodwill. We said we were from Israel and one of the Igbo guards told us he liked the Jews. We joked that we were also Igbo, and with a wave of his hand he whisked us through without opening up the bags.

This story is not over. The Igbo in Nigeria who are living as Jews are sure their ancestors were Jews and although the traditions were lost, they are merely re-adopting the practices. Most of them see themselves more as baalei teshuvah than potential geirim, and for the most part, they are less interested in hearing about giyur. Still, they told us they want to be real Jews. Some told us they want to move to Israel — but in practice they are also proud Igbos and don’t want to leave their homeland.

They are part of a diverse Judaizing phenomenon of non-Jews in Africa, South America, and Asia that’s happening below the radar — and we’re grateful for the opportunity to have met many of the players. What will ultimately happen to these groups? We are not sure, but a play like this in Jewish history has never made its debut in such a manner. Only time holds the answers.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 662)