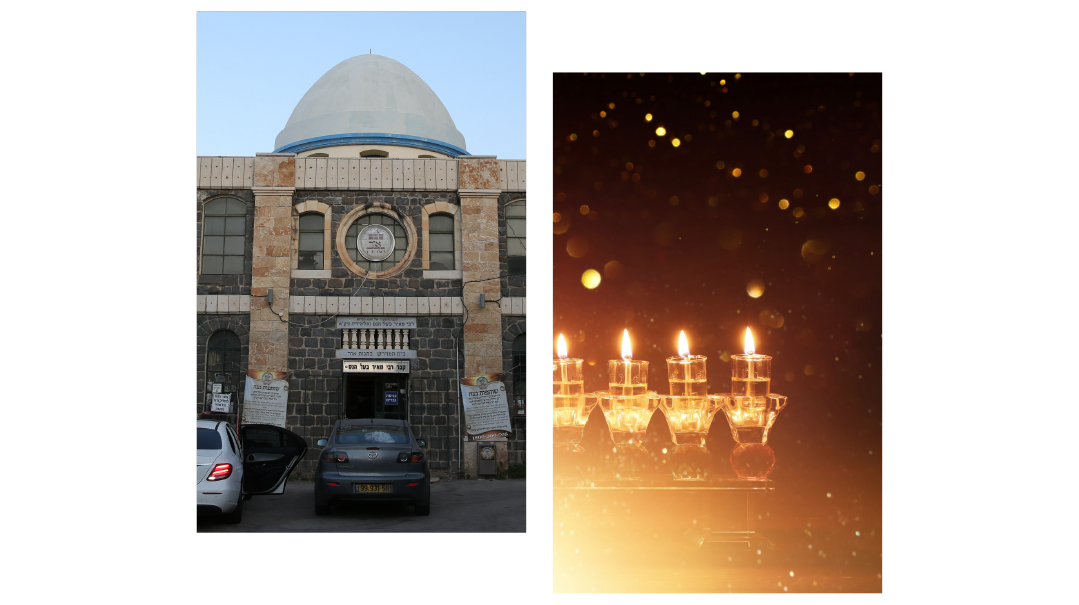

Weekly Wedding

| February 7, 2023As the end of Shabbos grows near, the kedushah only intensifies, taking us to an entirely new realm altogether

WE tend to think of Shabbos as a 24-hour oasis of heightened spirituality. But while of course that is true, it’s more nuanced than that. Shabbos is a world of its own, with multiple climates and varying dimensions. The spiritual uplift of Friday night is different from that of Shabbos day, and, as the end of Shabbos grows near, the kedushah only intensifies, taking us to an entirely new realm altogether.

Let’s explore these mystical concepts, demonstrating how each of these stages is reflected by the various tefillos and minhagim we observe throughout Shabbos.

- The Avudraham points out a discrepancy between the three tefillos we recite on the weekdays and the three tefillos we recite on Shabbos. During the weekdays, the words of all three Shemoneh Esrehs are the same. On Shabbos, however, there are entirely separate sets of wording for the respective Shemoneh Esrehs . On Friday night we say “Atah Kidashta,” on Shabbos morning we say “Yismach Moshe,” and on Shabbos afternoon we say “Atah Echad.”

The Avudraham explains that the varying verbiage reflects the different elements of kedushah that are present throughout Shabbos. Shabbos is a union between Klal Yisrael and Hashem, and it takes on the pattern of a halachic marriage. It begins with kiddushin, is followed by nisu’in, and culminates with yichud.

Corresponding to the stage of kiddushin, says the Avudraham, is the tefillah of “Atah Kidashta.” Corresponding to the nisu’in is the tefillah “Yismach Moshe” because it is after the nisu’in that the rejoicing of the wedding celebration begins. And corresponding to the yichud element, which takes place on Shabbos afternoon, is the tefillah “Atah Echad.”

- The Avudraham then offers another elucidation, this time in the name of Rabbeinu Klonymos. In this second explanation, the Avudraham connects the three disparate tefillos of Shabbos to three especially significant Shabbosos in history.

The first is Shabbos Bereishis, the very first Shabbos, which culminated Maaseh Bereishis. There’s the Shabbos whereupon the Torah was given (as the gemara in Shabbos concludes, according to all opinions, the Torah was given on Shabbos). And then there is the Yom Shekulo Shabbos, which we will merit with the coming of Mashiach.

Maariv of Friday night, explains the Avudraham, which begins with the paragraph “Vayechulu haShamayim,” alludes to the initial Shabbos of Creation. Shacharis of Shabbos morning, which contains the reference to Moshe Rabbeinu descending from Har Sinai holding the Luchos, corresponds with Matan Torah. And Minchah, which begins with “Atah Echad v’Shimcha Echad” is hinting to the ultimate Unity that will be revealed with the coming of Mashiach.

- While ostensibly the Avudraham is teaching two different approaches, Rav Avrohom, the son of the Vilna Gaon, explains that these two explanations really complement each other.

Friday night captures the energies of the first Shabbos of all time, as well as that of a kiddushin. This is because Chazal teach us that the creation of the world was for the sake of Klal Yisrael — bishvil Yisrael shenikra Reishis. Since the world’s creation was the first stage of the relationship between Hashem and Klal Yisrael, it is akin to a kiddushin.

Shabbos day relates to the Shabbos of Matan Torah, as well to the stage of nisu’in. This is reflected by the fact that Hashem held Har Sinai above us, just like a couple stands under a chuppah.

Finally, Shabbos afternoon embodies the character of both the Yom Shekulo Shabbos as well as the stage of yichud. When Mashiach comes, we will experience the ultimate unity of “bayom hahu yihyeh Hashem Echad u’Shemo Echad.”

- The idea that Friday night and Shabbos day are defined by two separate spiritual experiences can be seen from the various tefillos and zemiros we recite.

According to the sifrei Kabbalah (see Ohr HaChaim, Vayikra 19:3), Friday night is aligned with the feminine dimension, while Shabbos day is associated with the masculine dimension. Further, we know that the word “shamor” alludes to the Torah’s negative commandments, while the word “zachor” refers to the positive commandments. Women are obligated in all negative commandments but are exempt from many positive commandments. This insight explains why we say “shamor v’zachor b’dibur echad” in Lecha Dodi on Friday night.

Many ask why we reverse “shamor v’zachor” from the way it appears in the Torah, where “zachor” precedes “shamor”. Rav Ovadiah Yosef answers that since we recite Lecha Dodi on Friday night, which is characterized by the female dimension, we place the “shamor” prior to the “zachor.”

Similarly, in the zemer “Kol Mekadeish,” which is sung on Friday night, we find the phrase “shamor l’kasdsho mibo’oh v’ad tzeiso.” Conversely, on Shabbos day, we emphasize the “zachor” theme, both in Kiddush as well as in the zemer “Baruch Keil Elyon” where we recite “zachor es yom haShabbos l’kadsho.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 948.

Oops! We could not locate your form.