We Won’t Let Go

| May 19, 2015We simply have a different, valid minhag

Your zeide was an Oberlander, tenaciously clinging to the old nusach and minhagim his family lived by for generations. But you live among 21st-century Yidden who are neatly grouped into categories of “chassid” or “Litvak.” Why hold on to those unfashionable customs, continuing to daven, dress, and act in the ancient style of a group whose ranks are shrinking?

If you’re an Oberlander, chassidim call you a Litvak and the litvish call you a chassid. But while the heimishe style of dress might look chassidish, an Oberlander Yid davens Nusach Ashkenaz and his minhagim bear a definite Ashkenaz stamp.

While the frum world tends to clump everyone into easily identifiable boxes, Oberlanders — Jews whose ancestors came to settle in the “highlands” [“Oberland”], or the northwestern part of Hungary, from neighboring Austria and Czechoslovakia (as opposed to the “lowlanders,” who later emigrated to the eastern territories from the borders of Galicia, Ukraine, and Romania) — bear their own distinct heritage, stubbornly clinging to the customs of their oft-misunderstood historic communities.

Your zeide lived in Nitra, in Unsdorf, in Paks, or in Szerdehel. He lived according to the mesorah of his fathers and grandfathers, the community following their rav in matters big and small, and the way forward was clear and uncompromising — there were no shortcuts yet no complications.

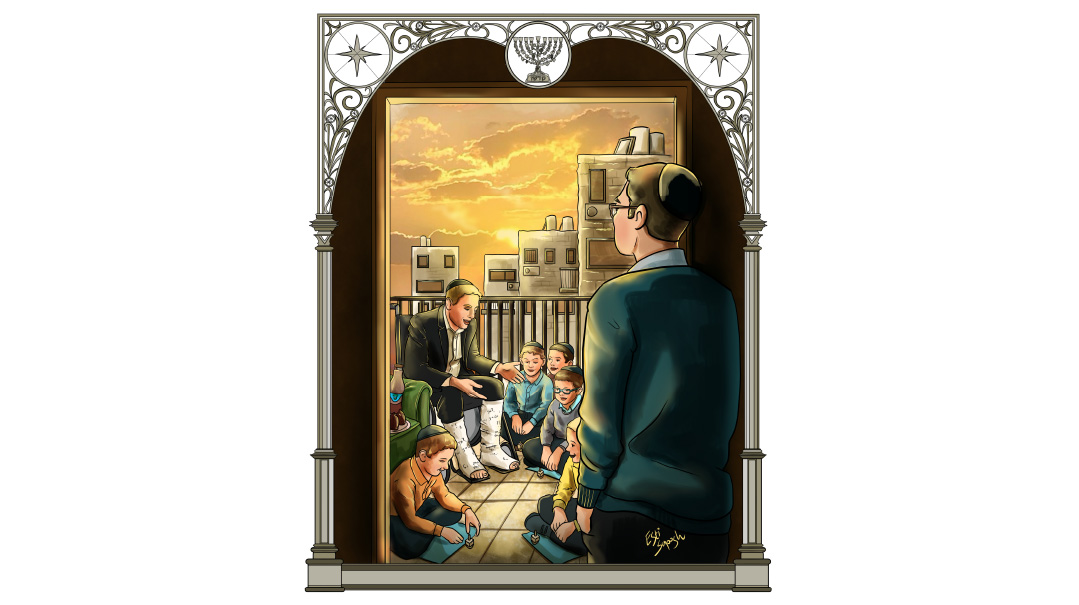

But you live in Yerushalayim, Boro Park, or London. On the corner is a chassidishe shtiebel, the next block yeshivah alumni. Your neighbors, lovely upright Yidden, are all serving the same G-d. So why hold on to the nusach and the minhagim that are so unfashionable today? Why continue to daven and dress in the style of a group that seems to be shrinking?

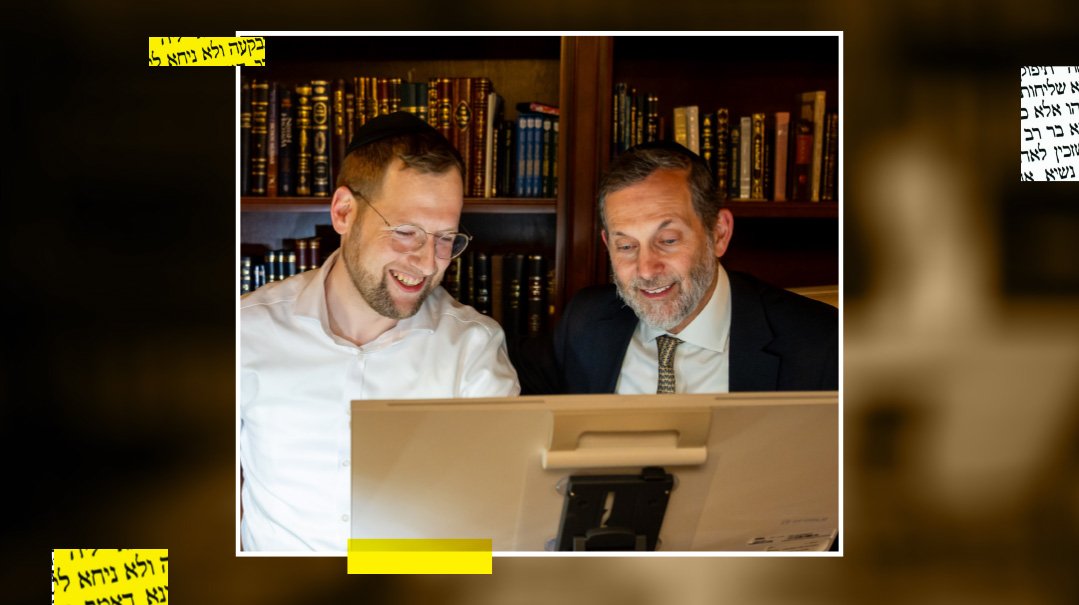

Reb Baruch Weissmandl is a scion of a prominent Oberlander family, a baal tefillah, and a staunch member of the Viener shul in Boro Park. He stands up for every last Hungarian custom, but his reasoning is not petty nor nostalgic.

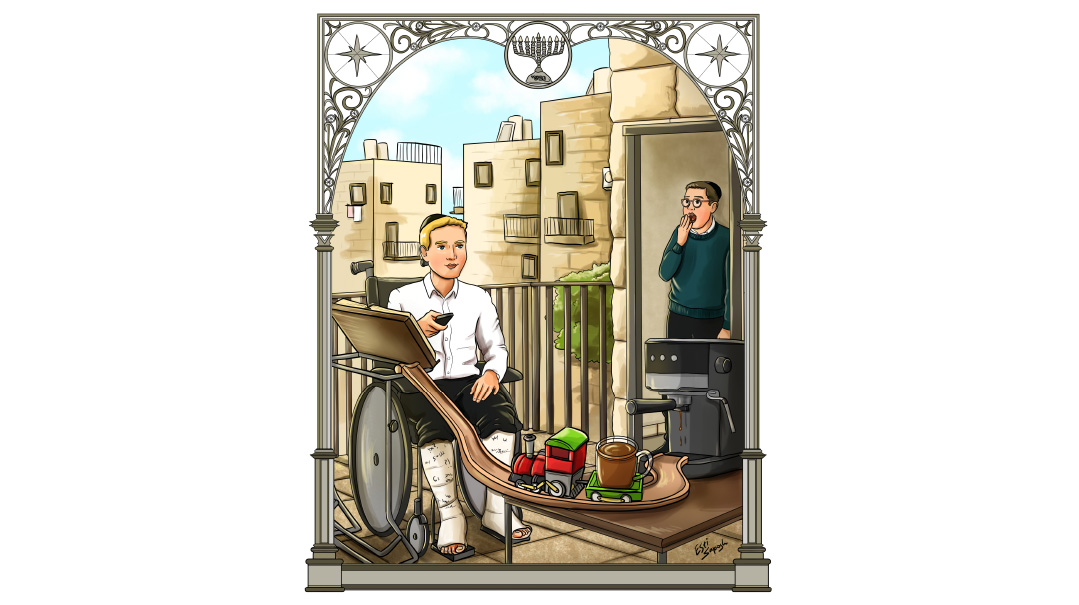

“Today people tell themselves, ‘I’m more educated than my father, I have bigger nisyonos, I face challenges he never faced — what did my father know about life today?’ We Hungarians don’t say that,” affirms Reb Weissmandl. “We’re hanging on to what our fathers and zeides did for generations. Why? Because if I change one thing today, tomorrow it’ll be something else, and what will hold me back? Let’s say today I’m rushing. But if I skip Tachanun, tomorrow it’ll be Korbanos… I’ve been fasting Beha”b [the Monday-Thursday-Monday fasts following a Yom Tov] all my life, but this year I have a cold. If I skip it and I live out the year, next year I probably won’t fast, and then I will have lost something…”

For the Oberlander, the whole of Yiddishkeit is a package deal, an all-encompassing way of life passed from father to son. Questioning or amputating one custom weakens the entire chain. In addition, they feel, a departure from traditional minhag might involve a halachic issue of “al titosh” or of breaking a neder, and is a question for a rav.

“I get a lot of flak for always upholding the Hungarian way,” Reb Baruch admits, “because there are instances where the Oberlander minhag differs from the Mishnah Berurah’s stance. There is no inherent problem with that, though. We are following our kehillah’s mesorah, which goes back to the Rishonim and the Baalei Tosafos. We simply have a different, valid minhag.”

Ideal Balabos

The northern and northwestern lands of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Oberland, included the ancient “Seven Kehillos” of Eisenstadt and six surrounding towns (including Mattersdorf) as well as Tirnau, Toppelchoin, Verbau, Galanta, Pistcany, Pressburg, and Vien — which existed as early as the time of the Rishonim (the Or Zarua, Terumas Hadeshen, and other Rishonim lived in Vien, Rav Avigdor Kara lived in Prague). These kehillos always maintained the old Ashkenaz ways, whereas in the southeastern areas of the Unterland, the communities moved toward chassidic tradition. Unterland included such famous communities as Ungvar, Sighet, Munkacs, and Satmar, which were originally Ashkenaz but strongly influenced by the Galician Jews who moved south to escape Galician poverty. Most of these towns, though, did maintain an Ashkenaz kehillah despite their chassidic majority, and the chassidic leader served as the rav of both kehillos.

The father and venerated leader of Oberland Jewry was the Chasam Sofer ztz”l. As rav and rosh yeshivah in Pressburg, this legendary leader, who passed away in 1839, raised the level of Torah scholarship, fought against the Enlightenment, and molded Austro-Hungarian Jewry, uniting them under his motto, “Chadash assur min haTorah” —whatever is new is forbidden. He and his descendants, the Sofer dynasty, and their disciples, strengthened the unique character and yiras Shamayim that has been the hallmark of Oberlander Yidden in the two centuries since.

This “Chadash assur min haTorah” philosophy is the source for Hungarian traditionalism, for the “stick-to-your-minhagim-no-matter-what” stance that Oberlanders have adopted in all areas of the their lives.

Most Oberlander towns had yeshivos — Galanta, Surany, Nitra, Szerdehel, Mattersdorf, and Szombathely to name a few. Yet in the Slovakian town known today as Bratislava, the prestigious Pressburg yeshivah was the scholastic crown of Hungarian Jewry, and it was here that most Oberlander rabbanim studied in their youth. The yeshivah also drew students from beyond Hungary, Austria, and Czechoslovakia, young men from both Eastern and Western Europe. It had earned governmental recognition, and even some German rabbanim sent sons there.

In the days of the Ksav Sofer, the Chasam Sofer’s son, Baron Rothschild once visited the yeshivah, and, looking around at the 300 bochurim in the beis medrash, he asked, “Pressburger Rav, why are you training 300 rabbanim here? Are there even enough rabbinical positions for them in the region?”

“I don’t need 300 rabbanim,” the Ksav Sofer corrected him. “I need two rabbanim, and 298 balebatim who will listen to them.”

That was the philosophy of the Oberlander yeshivos, differentiating them from the later Lithuanian model. Most young men were expected to go into business and support their families. Their yeshivah years were not intended to mold rabbanim or long-time kollel learners, but rather to nurture a special brand of erliche balabatim who would establish distinguished Torah homes.

The term “Oberlander balabos” describes this ideal Oberland layman, product of a Hungarian yeshivah. He spends his day in business, yet rises early to learn for some hours in the morning and never neglects to attend his all-important “Shas chevra” and to prepare and learn in his free hours. He accepts daas Torah, toeing the line of every last law and custom like a loyal soldier. The chinuch of his children is a priority, and his personal conduct is their Shulchan Aruch.

Oops! We could not locate your form.