Watch Them Grow

| October 24, 2023How OT and PT can set your child on a path to success

The limp, motionless form of my three-month-old daughter disappeared into the depths of the MRI machine. Terms like “genetic disorder” and “brain abnormality” floated through my mind as the inexorable noise of the MRI machine filled the room. It all felt like a distorted dream. How did I end up here?

When Rivky was born, none of us noticed anything worrisome. But as the weeks passed, there was a slight sense of unease. Rivky would scream when placed on her stomach, and she seemed to have a hard time lifting her head. Her movements looked slower and less energetic than those of her siblings. Over summer vacation there was little change, and the anxiety grew acute. When I described what was happening to the pediatrician over the phone, he was baffled and recommended some testing at a local hospital.

Rivky was poked, prodded, and examined by what seemed like the entire medical establishment. Subjected to endless blood tests, examined for illnesses I had never heard of, she was finally recommended for a brain scan. It was a draining, three-day process that left us terrified.

And then the hospital physical therapist bustled into the room.

“It looks like Rivky needs physical therapy,” she announced. “This baby has weak muscle tone. Weekly sessions with a PT specializing in infant development should help.”

She was right. The brain scans were normal. There were no genetic disorders. Within a year of beginning physical therapy, Rivky met all her milestones. We endured so much anguish and uncertainty when the issue was relatively simple.

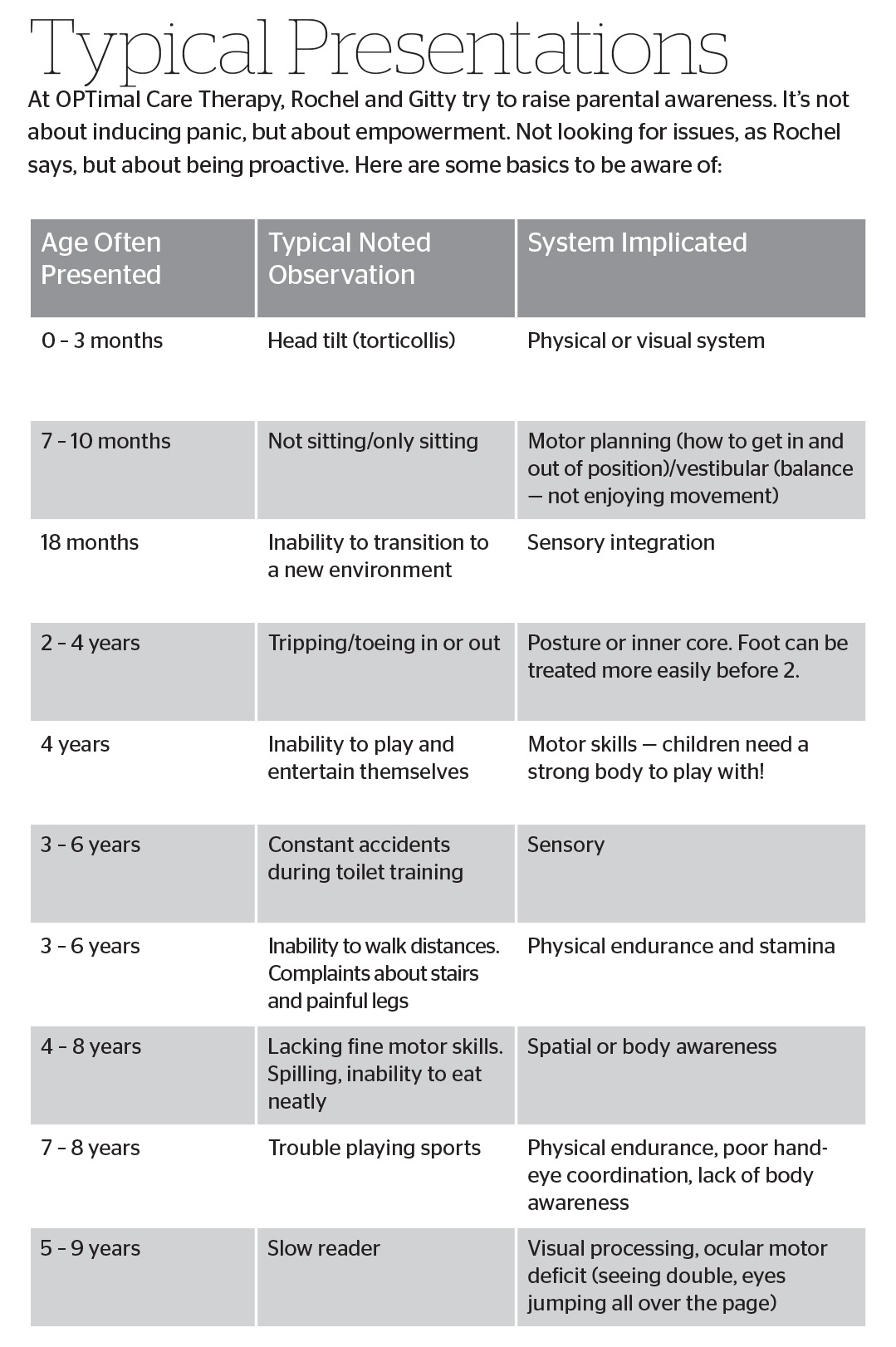

According to Rochel Feinstein PT, DPT, PCS, and Gitty Zelczer M.S., OTR/L, the duo behind OPTimal Care Therapy Center in Lakewood, New Jersey, my story is not as unique as I’d thought it was.

“How often does this happen?” I ask them curiously. “I know our case was atypical, but how often do you encounter basic misdiagnoses, where kids really have an OT or PT issue?”

“Every single day,” comes the swift response.

Every. Single. Day?

Therapy Explained

In the simplest sense, a physical therapist works to improve a person’s ability to move his/her body, while an occupational therapist focuses on improving a person’s ability to do daily activities. But there’s definitely an overlap. Research shows that OT and PT services are often complementary. The physical therapist works on strengthening the musculoskeletal system in various ways, and the occupational therapist focuses on teaching the strengthened patient to implement this into daily activities. Together they can create a pathway to success.

Think of it this way: Sensory pathways travel upward — you touch something soft, and the message gets sent to your brain, so you feel the texture. Motor pathways travel downward — your brain tells your arms to catch a ball. Both pathways need to work together to ensure optimal success.

Gitty, the OT of the OPTimal duo explains: “Occupational therapists help people learn how to process sensory information, which includes understanding whether each system exhibits good function/motor skills. But what you might not realize is that in addition to our five main senses — touch, sight, hearing, taste, and smell — there are the “hidden senses” of proprioception (our sense of body awareness) and vestibular function (our sense of movement and balance).

“So, for example, a person might need OT because their auditory sense is off, like Elisheva*, an adorable three-year-old I treated recently. Elisheva exhibited extreme behaviors. Elisheva was anxious all the time, constantly crying. She seemed to feel overwhelmed by loud noises and lots of people. It was becoming impossible for her mother to take her anywhere, and her morah was having a lot of trouble dealing with her.

“After watching Elisheva’s loud reaction to my clinic (a hysterical tantrum when she heard the noise of some other children shouting), it was clear that her issue was one of sensory integration. Her auditory system was too responsive, magnifying noise and causing a flight-or-fight response. It’s no wonder Elisheva reacted how she did!

“I used several auditory/music programs to help Elisheva slowly accustom herself to different frequencies of sound. This type of treatment helps ‘calm’ the nervous system, stopping it from over-processing information. In a few weeks, Elisheva was thriving.”

There’re also the hidden senses. A child with poor proprioception — a sense of balance — might fall a lot or act very clumsy, or they may drop or bump into things. If a child’s vestibular sense is impaired, they can be constantly dizzy. Babies with vestibular disorders often can’t sit, crawl, or stand at the proper age.

In addition to OT, babies and children will benefit from PT. “Physical therapy has many facets,” Rochel explains. A “movement specialist,” she is certified in pediatrics and development, as well as in the fields of posture and scoliosis. Rochel explains that physical therapists maintain and restore maximum movement and functional ability throughout the lifespan. “Any child with a developmental delay related to the musculoskeletal system will fall into this category. We prevent impairments and provide intervention and treatment. This includes basic strengthening, gait, and posture/alignment, coordination and balance, as well as promoting general physical wellbeing.”

There’s a common denominator between the slouching teenage girl, the three-year-old who is “pigeon-toed,” the 20-year-old suffering from nerve damage in his hands, the adolescent boy whose pediatrician notices an ominous curvature to his spine — the beginning of scoliosis — the middle-aged woman who suffers constant headaches, the active ten-year-old sports enthusiast who recently had a concussion, and the 80-year-old stroke patient. All of them can benefit from the broad and wide-ranging field of physical therapy.

“One of the most common things I see in my clinic is children who fall out of their chairs,” Rochel says. “I recently saw Reuven, an eight-year-old boy whose principal was pressuring the parents to put him on medication. Apparently, he was disturbing the entire class because he couldn’t sit in his chair. He was always falling out of his seat, and his rebbi was not pleased. Reuven also had a hard time keeping up with his peers physically during recess and gym.

“When I evaluated him, I saw that his body was ‘floppy.’ His joints were very flexible, his arms and legs seemed limp, and his posture was a tired slouch. This was clearly a case of low muscle tone, not Reuven trying to disturb his classmates. He simply couldn’t sit in his chair for so long.

“It took a few months of various strengthening exercises — such as crawling over different surfaces, climbing on walls of various difficulties, squats, and bouncing on a therapy ball — but he was finally able to sit in class.”

Delving into Development

Both Rochel and Gitty progressed far past their original certifications, becoming fascinated by how infants and children develop. Why give children tools to manage their symptoms, they thought, when the option exists to work with each child on a developmental level? Instead of manipulating the environment to suit the child, integrate the child to be successful in every environment.

Expert developmental therapists can examine even newborns and discern if their movement patterns are typical or atypical, Rochel explains. An early diagnosis and treatment save hours of heartache later on. The newborn brain is malleable and easily treated and changed — something that becomes more difficult as the child develops further.

Rochel tells the story of eight-month-old Shimmy. He was born premature, at 35 weeks. Shimmy suffered from constant upper respiratory infections. He also drooled far more than the average infant and didn’t seem extremely interested in eating. When he took his bottle, he made very loud slurping and sucking noises.

“During the evaluation, I noticed that Shimmy didn’t suck on his bottle properly, and he’d be wet with leaked milk long before he finished eating. He was unable to roll over, and he had difficulty reaching for toys. Clearly, Shimmy’s motor and oral skills were underdeveloped. I was also able to see one reason for Shimmy’s constant respiratory problems: his chest/ribcage muscles were immature, and there was evident stiffness and swelling.

“I treated Shimmy with tummy time, which is extremely important to strengthen his core. He had multiple short sessions and breaks in between to increase his stamina. I also engaged Shimmy in stretches to maintain his range of movement — for example, leg lifts, and crossing his legs and arms over to the opposite sides of his body. Oral skills are enhanced by gentle facial massage, putting a clean object in Shimmy’s mouth to encourage sucking, and then pulling on it gently to encourage him to suck harder. There are many types of oral chew toys of varying degrees of hardness that are also excellent for building oral strength.

“We also strengthened Shimmy’s rib cage and muscles through gentle manipulation. Lying on his back or over a therapy ball, Shimmy’s ribs were moved and massaged one by one to free the muscles and ease the tightness.”

Since Shimmy was premature, Rochel says, his therapy treatment lasted months, as he encountered ever-new milestones to achieve. He “graduated” right before his second birthday.

Shimmy is not an anomaly, Rochel says. Premature babies have immature and underdeveloped systems and are often treated as “preemies” until their second birthday, when they are finally on par with their peers (although this may take longer for some premature babies). The earlier these deficiencies are targeted, the more effective therapy will be. And parents are an integral part of the treatment plan. Each preemie is different, depending on their gestational age at birth and their specific needs. Parents should receive support from therapists, with guided exercises they can perform at home. This can make all the difference in the child’s development.

The brain’s neuroplasticity — its incredible ability to renew and correct itself — means that it’s not only babies who can learn to rewire their brains. Stroke patients who are middle-aged or older can do so much, even after significant damage.

Remember all those olfactory exercises Covid patients used to regain their sense of smell? Same idea.

But it goes way beyond that. Mora Leeb was nine months old when doctors surgically removed the left side of her brain to stop her constant seizures. Initially paralyzed on her right side (which is controlled by the left side of the brain), Mora endured years of intense therapy. At 15 years old today, Mora can walk and talk. The right side of her brain has rewired itself to do double duty, and Mora is now a mostly typical 15-year-old.

Differential Diagnosis

Any child who isn’t doing well in a specific area should be seen by a professional, says Rochel. After the doctor confirms there’s no medical problem, an OT or PT should evaluate the child to check for a developmental delay. And sometimes, even when doctors suspect a medical issue, therapy can help.

The doctors concur. “We’re pretty dependent on PT and OT,” says Dr. Ahron Rubinstein, an ER doctor who works at St. Francis Hospital in Chicago. “I don’t know any physician who doesn’t rely on them. Most patients who enter the ICU will end up having an evaluation done by a therapist, or multiple therapists.”

And it’s not only hospital patients. As Dr. Rubinstein explains, while some people need therapists to teach them basic living skills after a stroke or an accident, others suffer from medical conditions that are dependent on therapy (joint issues or chronic pain).

“Sometimes patients don’t know how to do exercises that are necessary for their health. Sometimes they need a therapist’s assistance. And sometimes, they’re simply not disciplined enough without regular therapy sessions. Either way, we doctors know that therapists are always a valuable part of treatment.”

When it comes to a child, like my daughter, after a pediatrician ascertains that there are no medical issues, why try to unravel the complex maze of specialists when a therapist can pinpoint the proper direction? Even more fundamentally, why head straight for aggressive and complicated solutions when the answer might be a few (or more) sessions of therapy?

But the answer is not always therapy, Rochel warns. “Sometimes further testing and specialists are warranted.” She recently had a case that was so complex, three other specialists were required to clarify all aspects of the child’s issues. “Differential diagnosis may require more than one professional. We refer children to ENTs, gastroenterologists, cardiologists, pulmonologists — the list goes on and on.” Children receive therapy only after all medical issues are clarified.

On the other side, Gitty says, “Misdiagnosis happens. We’ll see a child who was diagnosed as having ADHD or a learning disability, but sometimes after a thorough evaluation we realize that the problem lies elsewhere. Difficulties in reading can be an ocular-motor problem, or a visual processing issue.

“We once saw an 18-month-old named Dovi who was diagnosed with severe reflux. Sometimes this can begin with weak muscles in the esophagus, causing poor swallowing patterns. There are different exercises a physical therapist can do to minimize a baby’s discomfort. But as we spoke to Dovi’s mother, a more puzzling picture emerged.

“Dovi was constantly carsick, and always screamed in elevators. He avoided tilting his neck upward and was unable to roll over. When placed on a changing table, we watched how he screamed in fear. He was clearly uncomfortable, and it wasn’t just reflux.

“Obviously babies can’t tell us what they feel, but Dovi’s behaviors informed us that he was uncomfortable with movement. He seemed nauseous and threw up when he was turned over quickly, a classic symptom of a vestibular issue. Dovi had a problem with his balance and the way his body processed movement. His muscles were also very weak because he avoided movement —he wouldn’t even reach for toys that caused him to turn his head.

“There are vestibular receptors in the inner ear that detect head positions and movement. During therapy sessions, I moved his head and body in specific ways to ‘teach’ his receptors to process movement correctly. This can involve gentle swinging exercises, leaning backward over an exercise ball, and going down slides, among other things. Rochel started to help Dovi strengthen his weak muscles with various exercises, for example, by encouraging him to turn his head with exciting toys and using a foam ‘wedge’ to help him get used to the muscle movements needed for rolling over.

“Medicine for reflux could only take Dovi so far. Fortunately, he had a full evaluation, where his underlying issues were brought to light, and both PT and OT made a tremendous difference.”

And it wasn’t only Dovi who was helped. Sometimes through a child’s therapy, adult family members recognize their own issues. Dovi’s paternal grandmother realized that she suffered similarly: She would get dizzy after rolling over in bed, hated car rides, and had avoided plane rides for years, since they made her sick for days afterward. After Dovi’s successful treatment, Bubby realized she had a vestibular issue and went for several sessions of therapy, where she did similar movement exercises to Dovi’s, with manipulations of her head, body, and eyes. Bubby recently went on her first successful airplane flight.

The Elephant in the Room

And then there’s the elephant in the room — ADHD. Nothing rouses furious debate like those four letters. To medicate or not to medicate is clearly not the only question.

Rochel and Gitty often evaluate children who were diagnosed with ADHD, only to discover they are merely suffering from sensory or motor issues, which can be taken care of. (One therapist mentioned that over the course of one especially hectic week, children were coming into her clinic every day with misdiagnosed ADHD. “It was out of control!”) Conversely, many sensory and motor issues are often part and parcel of the child properly diagnosed with ADHD, which can make things confusing for parents. Does their child have ADHD or not? Either way, a comprehensive evaluation by an OT and PT is often a wise choice.

“ADHD is not just a stand-alone neurological disorder,” Gitty explains. “It’s often accompanied by a sensory/body issue.” Significantly more than half of children with ADHD are also diagnosed with an issue that can be helped by PT or OT. For example, a shorter attention span is often associated with ADHD, but that can also be partly due to poor motor control, or a heightened sensitivity to sensory surroundings that make it nearly impossible for a child to filter out sensations and focus on one aspect of his environment (such as the teacher).

These children may also suffer from poor tactile, proprioceptive, or vestibular discrimination, which causes them to be less grounded, and in need of constant movement, along with an impulsive urge to touch items and fidget. Sensory and motor issues are often part of the ADHD package, and it’s important to ensure that all underlying issues are being addressed to improve long-term function. When medicine is the only intervention, children are left with sensory and motor deficits that follow them into adulthood.

Teresa May-Benson ScD, OTR/L, FAOTA, has researched this aspect of ADHD. May-Benson asserts that an evaluation by “a qualified occupational therapist is vital to adequately address the challenges experienced by children [with ADHD].” Medication is sometimes necessary, but there are times a child is taking medication he wouldn’t need if his challenges were addressed properly through therapy. Medicine is change for the moment — therapy is change for a lifetime.

It’s not just about taking a pill, but about making the pill a smaller part of the picture. Because there’s so much more to see.

And as Rochel and Gitty have shown us, as long as we’re alive, we can change and correct physical habits and sensory issues. With targeted therapy, patience, and time, many presenting issues can be completely resolved.

One parent puts it simply: “It’s a miracle.”

Case Files

I’m fascinated by Rochel’s and Gitty’s stories, and more: By the idea that there are things we can try at home to improve our kids’ sensory integration.

Note: As in all the case files presented in this article, names and identifying details have been altered to protect privacy.

CASE FILE 1

Patient: Eli is a morose ten-year-old who clearly doesn’t want to communicate during our evaluation. He’s having trouble socially, and although very bright, doesn’t play with his peers at recess. When coaxed, he refuses, exhibiting symptoms of anxiety.

Apparently, Eli has a hard time playing baseball — his mother says he almost never hits the ball. His self-esteem has plummeted since he can’t join the game with his friends. He also complains that he’s “too tired” to play. On long family walks or hikes, Eli can’t keep up. He lags behind, and his negative attitude toward any physical activity often affects the rest of his family.

During the course of our conversation, it becomes clear that Eli’s father thinks therapy is a waste of time.

“Some kids are good at sports, and some are good at learning. Eli’s just not an athlete!” he announces.

Diagnosis: We test key muscles in Eli’s arms, legs, and core using a dynamometer, a device that can measure force by testing a person’s resistance. Eli falls on the lower end of the spectrum. His muscle strength and stamina are clearly below average.

During the OT evaluation, among other tests, Eli cuts paper and has to dribble and throw a ball through a hoop. His cutting is uneven, and he finds it almost impossible to dribble the ball for any length of time. His balls all seem to miss the basket. It is clear that Eli’s hand-eye coordination is extremely poor.

Treatment: In PT, Eli works hard at various exercises, climbing and swinging on courses that gradually grow more demanding. His parents are advised to take him swimming a few times a week, as this is an excellent way for weaker muscles to gain strength. Body-weight exercises, where Eli pushes against his own body in squats, planks, and push-ups, slowly build his strength and endurance.

In his OT sessions, Eli’s hand-eye coordination is developed. He works on eye movements, eye teaming (so both eyes work together), saccades (fast eye movements from point A to point B), and visual vestibular function (keeping eyes steady during body movements).

One exercise involves Eli holding a single object and fixing his eyes on it. Slowly, Eli moves the object, his head, and eyes in the same direction for 30 seconds. This helps his eyes work together. Another activity, used to improve his visual saccades (fast eye movements), is to try to hit two alternating targets with a ball, without turning his head — using only his eyes to track the ball.

Within a few weeks there is visible improvement, and within a few months, Eli is no longer a patient. His ability to play sports with his peers has improved, his self-esteem has surged, and recess is no longer the worst part of his day.

“People used to compartmentalize kids,” Gitty says. “They would say, ‘This kid is athletic, this kid is the reader,’ and so on. However, while kids have strengths and weaknesses, if a child is extremely weak in a specific area, check it out. There’s often a solution!”

Takeaway: While home activities are not a replacement for therapy, they can enhance therapy and provide children with immeasurable benefits. Many therapy sessions end with some form of “homework” that empower parents to participate in their child’s treatment. Swimming, full-body exercise, routine physical activity, and the two hand-eye coordination exercises can all be done at home.

CASE FILE 2

Patient: Bracha is a sweet eight-year-old who chatters happily throughout the session. Her mother explains that nobody wants to sit next to her at mealtimes, since the sight is so unpleasant. Bracha eats very messily, and her food splashes everywhere, which frustrates her. She doesn’t seem aware when she pulls the tablecloth off the table and is always extremely dirty after mealtimes. Her classmates get disgusted, leading Bracha to have problems with friends in school. Bracha complains that her hands feel like she is always wearing gloves.

Diagnosis: After a detailed questionnaire and watching Bracha try to manipulate different objects with her fingers, it’s clear that Bracha’s issue is tactile — her fingers don’t process feelings properly. She is constantly touching objects and moves into others’ personal space. When writing, Bracha holds her pencil in an overly strong grip and sometimes rips the paper with the force of her pressure.

Her tactile issues make it difficult for Bracha to manage utensils or put her food in the right place (her mouth). There is always a dirty ring around her mouth, which she simply doesn’t feel.

Treatment: There are seven touch receptors in the skin, and our tactile discrimination system — the ability to tell what you’re feeling through the sense of touch alone — can only work accurately when each of them is developed. To work on her tactile sense, Bracha finger-paints, rolls over different textured surfaces, explores sensory bins filled with small objects, makes clay sculptures, and embarks on a texture scavenger hunt — finding objects in the room that have different textures (soft, sticky, squishy, etc.).

Bracha’s new sensory “diet” helps her distinguish textures much more accurately. A few months into therapy, Bracha manages her utensils beautifully, and her classmates no longer avoid her. Bracha is much happier at school, and life at home is more pleasant for everyone.

Takeaway: Any of these activities can be beneficial for a child who has low tactile sensitivity and craves more tactile stimulation.

CASE FILE 3

Patient: Chaim is a third-grade boy who has been getting kriah help since primary. He is pulled out of class four times a week. His parents notice that he skips lines and loses his place frequently, and his reading is slow and labored. Chaim hates reading and complains bitterly that his eyes always get tired, and that reading gives him headaches. Chaim had a basic vision screening, and his acuity was normal. His parents are at a loss.

Diagnosis: During the evaluation, Chaim whispers when reading, tilts his head to see the words better, and skips a few sentences. He reads slowly and laboriously, and when he’s finished, he complains that his eyes “hurt.”

Suspecting an ocular-motor issue (hand-eye coordination), the OT has Chaim follow a ball bounced off the wall using only his eyes — without turning his head. Chaim gives up and refuses to cooperate further since this is so difficult for him.

Treatment: Ocular-motor training is essential for Chaim. Some of the exercises Chaim works at are hitting a balloon with a tennis racket (balloons move more slowly than balls and are easier to track), tossing bean bags, and following a marble as it speeds through a marble run. As his ability improves, Chaim does his exercises while sitting on a therapy ball, then standing on a wobble board, or even swinging forward and backward.

It takes around half a year, but Chaim’s rebbi reports a drastic difference in his ability to read and keep his finger on the correct place. Chaim’s confidence soars, and the nightly kriah battles become a relic of the past.

Takeaway: Besides the above exercises, here is an easy exercise that targets “eye jumps” — the quick back-and-forth motion of the eyes. Have your child extend their arms in front of their body and lift their hands about shoulder height. They should make a fist with a thumbs-up on either side. The child should gaze at the left thumb and then jump their eyes to the right thumb. This can be repeated multiple times, until the eyes can smoothly transition from one thumb to the other.

*All names and identifying details have been changed. Some of the “case files” narrated in the article are composite case studies.

A Success Story

I spoke with Esti, whose baby was treated with OT and PT.

SG: Hi, Esti! I understand that PT and OT helped your baby. Can you tell me about what happened? How did it all begin?

E: When my baby was around two or three weeks old, her eyes started moving and jumping in the strangest way. I was panicking, thinking she was having multiple seizures. When she was four weeks, we took her to CHOP to have her evaluated by a top neurologist. He suspected she might have epilepsy.

SG: That sounds terrifying! What happened at the hospital?

E: It was pretty traumatizing. Wires were taped all over her head, and the doctor tried to induce seizures. When that wasn’t successful, the neuro-ophthalmologist at CHOP concluded that the nerves inside her eyes weren’t working, and that my baby would need serious eye surgery. I was devastated.

SG: How did you end up getting from eye surgery to therapy?

E: It was totally random — in other words, completely bashert! I was at a café and saw a friend. She mentioned that she was constantly taking a few of her children to these amazing therapists, and she gave me their number. The practice I used usually has a long waiting list, but because so much can be done to make a real difference with very little babies, they agreed to take my daughter.

SG: That’s amazing. What did the therapists do with your daughter?

E: My baby was always dizzy because of her jumping eyes, so she was afraid of movement. Her development was delayed in so many areas, and she just wasn’t meeting her milestones.

Gitty Zelcer did vision and vestibular exercises with her. She worked especially hard on my baby’s vestibular system, which is all about the body’s movement system/head movements, and she also focused on eye exercises to integrate pathways in her brain to help her movement system and eyes work properly.

Rochel Feinstein helped strengthen her muscles and work on her motor development so she would progress to meeting all her milestones correctly.

SG: What was the result of all this therapy?

E: At nine months, I brought my baby back to the neuro-ophthalmologist who initially recommended eye surgery. Her eyes were much more stable, and she was developing beautifully. This neuro-ophthalmologist was top in his field — the head of his department — and he couldn’t believe what he was seeing. “I have a new respect for therapists!” he exclaimed after examining her.

SG: How is your daughter doing now?

E: She’s 17 months old, and she’s working on her walking. The progress is unbelievable! Interestingly enough, she was diagnosed with farsightedness during a routine eye test at her pediatrician. I was convinced it couldn’t be true because she had been examined by such a respected neuro-ophthalmologist. However, I realized something important — all the fancy doctors couldn’t see this simple issue because they were simply too specialized! My little girl will soon be getting glasses, and I’m sure that will lead to further progress.

Credentials Count!

Parents want the best for their children — but what’s the best? In the OT and PT fields, there are a plethora of therapists and methods. How do parents choose from among a bewildering array of services?

“Parents need to do their homework when searching for a therapist. Don’t only trust the word ‘therapist.’ Check credentials and specialties. Do they match your child’s needs? After an initial evaluation, you should know what areas your child needs to work on. Don’t be afraid to ask,” say the experts. A competent therapist will be able to answer these questions to your satisfaction.

According to many authorities, no one is a “specialist” until they’ve been working at least ten years in their field. If your child’s case is complex, find a true specialist.

If change is not apparent, or a regression occurs, that should be a red flag.

Every month makes a difference for a positive outcome, so don’t delay!

Choosing the right therapist for your child is what makes therapy successful.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 865)

Oops! We could not locate your form.