Wake-Up Call

On the line with Martin Cooper, inventor of the very first cell phone

Photos Jeff Antenore

Fifty years ago, Martin Cooper stood on a Manhattan street corner, pulled out a mammoth transmitter-like contraption, punched in a few numbers and dialed his competitor — who became the first-ever recipient of a cellular call. The disgruntled colleague shouldn’t have been too upset, though. Half a century later, he’s surely carrying an offshoot of that phone in his pocket. And as for 95-year-old Marty Cooper? He’s still trying to make the world a better place

Martin Cooper is the fellow who cut the cord, who unshackled humanity from the limitations of the telephone wire, who bequeathed the world with one of the top ten inventions of the 20th century.

It’s been 50 years since that day in April of 1973, when Marty Cooper, then an engineer at a tenacious technology company called Motorola, and head of its communications division, stood on a Manhattan streetcorner, punched a phone number into a large box with a digit panel that looked like the then-ultra-modern push-button phones, and put it to his ear while passersby wondered what on earth he was doing with that mammoth contraption.

Cooper dialed the number of Joel Engel, his counterpart at Motorola’s rival Bell Laboratories, the research division of AT&T. He couldn’t wait to hear Joel’s expression when he’d pick up.

The year before, Bell Labs had decided to double down on an engineering track to create a car phone in what it believed was the communication model of the future, but Cooper was worried. He didn’t want to see a phone tethered to a car as the standard of mobile communication — he believed it would be possible for a phone to be an extension of a person, who shouldn’t be relegated to being next to a wire on the wall or sitting in a car while connecting to another person. Cooper, for his part, set out to create a mobile phone that could fit in a person’s pocket. Within a year, his team had the first working cellphone system — an amazing feat of engineering, even if that early clunker couldn’t quite fit into a pocket or purse.

“Joel,” Cooper spoke into the box, “this is Marty. I’m calling you from a real handheld, portable cell phone.”

Cooper doesn’t remember Joel’s exact response, but he knew Bell Labs was pretty annoyed. At the time, Motorola was a small player on the fringe of AT&T’s monopoly, and they thought it was impertinent for a company like Motorola to go after them and compete on their turf.

While it took another ten years for the first commercial cellular phone service to begin operating in the US (the Motorola Dynatac 8000X, released in 1983, took ten hours to fully charge for 30 minutes of talk time and cost $4,000, plus 50 cents per minute of talking), and portable mobile phones didn’t make significant inroads with consumers until the early 1990s, Cooper’s Dynatac prototype was a technological breakthrough for Motorola, helping it achieve its goal of winning FCC permission for private companies to operate a wireless communications network over radio frequencies.

Who would have had an inkling that Martin Cooper, as a child growing up in Winnipeg and Chicago, would create the invention of the century?

Bringing People Together

Now a spritely 95 and finally retired, Marty Cooper maintains an active interest in every bend and curve in the dizzying road toward the next generation of his invention (he says he keeps his mind active by doing the New York Times crossword puzzle every day). With the cellphone now 50 years old and finally, as he envisioned, in everyone’s pocket, what will its future hold?

Cooper, an affable, white-bearded gentleman, chuckles at my suggestion that he’s the person, more than any other, who has brought people together.

“I wouldn’t stretch it that far,” he says, “but I did invent the first portable cell phone.”

As if on cue, he reaches into his drawer and pulls out the very first cellphone, a white hulk whose claim to fame was what it was missing the wire. It’s hard to imagine such a contraption hooking onto a belt or slipping into a pocket, but this was it — the dawn of the cell phone age, with all the excitement of seeing an early version of the Wright Brothers’ flying contraption.

“This thing weighs over two pounds and had a battery life of about 25 minutes of talking,” he says, “but that wasn’t really a problem because you couldn’t hold this phone for 25 minutes, it was so heavy.”

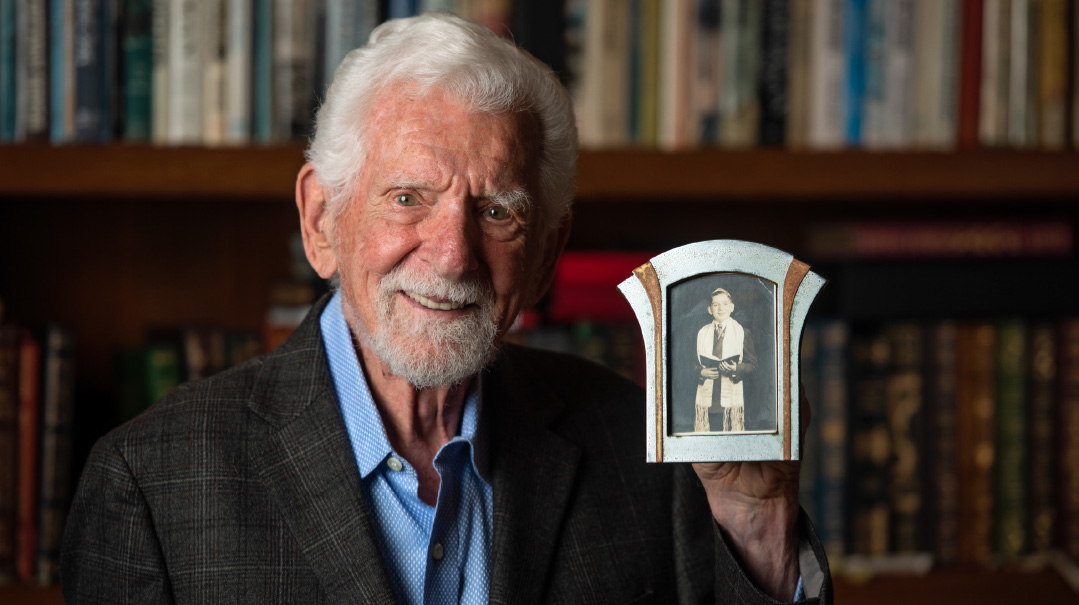

A delightful fellow with a ready laugh and a pride in his Jewishness, Cooper loves to “bagel,” throwing in Yiddish expressions and regaling me with anecdotes of his two great-granddaughters and of his double bar mitzvah.

“I may not be a great Jew,” he confesses, “but I’ve been bar mitzvahed twice.” When he turned 83, I guessed? Many secular Jews repeat the bar mitzvah 13 years after turning 70, the traditional lifespan of man.

“That’s right. You know about that tradition,” he responds. “I read from the Torah. Today, though, my Hebrew is very, very rusty.”

He now lives in an opulent beachfront villa in California at the insistence of his second wife, Arlene Harris. “I don’t want to make you jealous, Yochonon, but when you’re my age, maybe you’ll be in California, too.”

Talk on the Go

Humanity’s quest for a device with the ability to talk while on the go began almost as soon as phones became popular. In 1926, Nikola Tesla, an early inventor who dabbled in wireless technology, predicted a future where people would be able “to communicate with one another instantly irrespective of distance” with the clarity of a face-to-face meeting using a device that “will fit in our vest pockets.”

On April 11, 1953, Mark Sullivan, the president of the Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Co., told an audience, “Just what form the future telephone will take is, of course, pure speculation. Here is my prophecy: In its final development, the telephone will be carried about by the individual, perhaps as we carry a watch today. It probably will require no dial or equivalent, and I think the users will be able to see each other, if they want, as they talk. Who knows, but it may actually translate from one language to another?”

A decade later, in April 1963 — exactly ten years before Cooper’s debut into history, an article published in the News Journal, a newspaper out of Mansfield, Ohio, blared the headline, “You’ll Be Able to Carry Phone in Pocket in Future.”

The world was waiting for its development. Cooper filled that void first, disregarding market analysts who predicted little enthusiasm for the product.

Boy, were they wrong. A Pew research survey from 2021 shows that 91 percent of the world’s adult population, or 7.3 billion people, owns a cell phone. In the United States, the number stands at 97 percent. The cell phone, and its child, the smartphone, is one of the most widely used and sold pieces of consumer technology. Nearly 1.8 billion phones are sold each year, mostly in China, India and the United States.

“I don’t think there’s any other invention that has affected every single person in the world in such a short period of time,” Cooper says. “Even for those few people in the world who don’t have cell phones, their lives are being improved because the cell phone exists. Even in Africa, millions of people moved out of severe poverty largely because the cell phone was there, which improved commerce and people’s lives.”

Cooper’s prototype took ten years to hit the shelves. When it finally did, in 1983, Motorola became the dominant leader in the industry for the next 15 years. They were then overtaken by the Finland-based Nokia, until 2012 when Samsung surpassed it and never let go of its leadership position.

The dependence on Cooper’s creation has its downside, too. A reviews.org survey of over 1,000 Americans this year found that 57 percent are “addicted” to their phones, checking it on average 144 times a day, beginning within ten minutes of awaking. About 75 percent see messages within five minutes of receiving them, spend four and a half hours on their phones, and feel uneasy leaving it at home. Half do not recall going 24 hours without their phone. The number of Americans who reported checking their phone as soon as they wake up went up ten percent in 2023 from the year before, and 82 percent said they would not evacuate their home in the event of a fire without taking their phone.

Of course, Cooper never predicted digital smartphone technology when he created his prototype — he just wanted people to be accessible and be able to talk to each other from wherever they happened to be. As the person who started this revolution, Cooper takes a nuanced view of the smartphone dilemma.

“Every invention has both positive and negative aspects,” he said. “As you can probably tell, I’m an optimist by nature, and I think things are getting better for human beings everywhere. I know there’s a lot of misery in the world, there’s a lot of unhappiness, but things are better now than they have been in the past and I think it’s going to keep getting better. In that context, the ability for us to communicate and work together is a very important factor.

“Just think about it, Yochonon. When Einstein, to give you an example, was tinkering with his formula of E = mc2, if he wanted to share his idea and work with somebody, he had to write a letter, put it in the mailbox, and a couple of weeks later the person would receive the letter and think about it for a few weeks before responding. The interchange could take months for just one conversation. Today, you can just pick up the phone or send an email, and you have instant communication. The productivity that happens is unimaginable.”

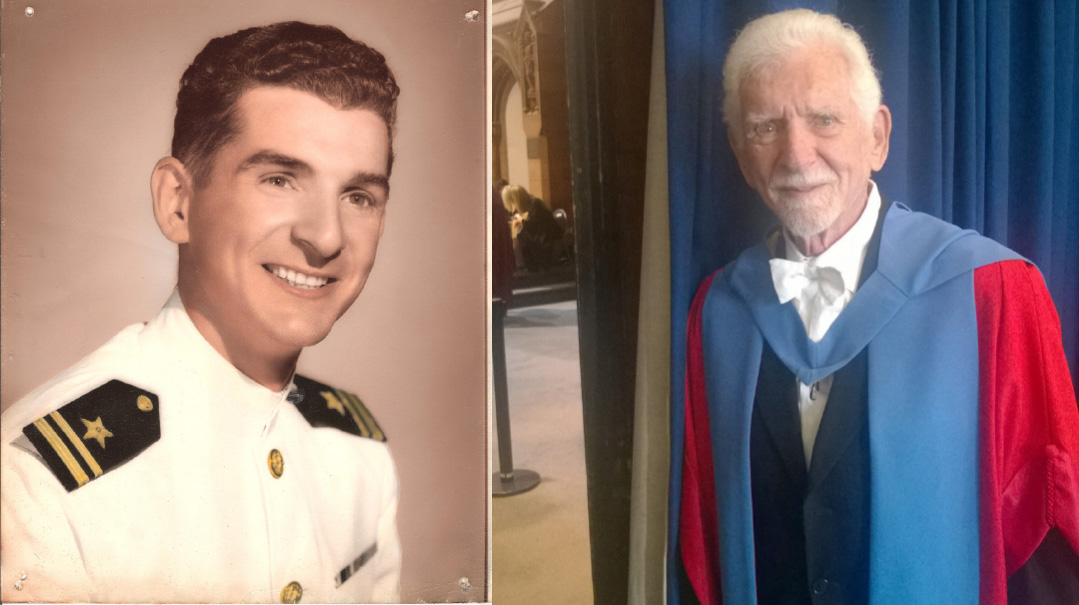

As a submarine officer during the Korean War, and as a recipient of an honorary doctorate from Illinois Institute of Technology, Marty always has a presence that made his team listen and take note

Short on Time

I ask Cooper what advice he has for how people can best harness the advantages of the cell phone without the liabilities.

He seems to appreciate the question, telling me, “nobody’s ever asked me that before. But you know, when you are respectful of other people, you have to understand that their time is valuable and your time is valuable. I try not to make phone calls unless they’re important. I use email, I occasionally will text, but I rarely use social media. I did tweet for a while — I have 8,000 Twitter followers, which is really nothing today. But I just didn’t find it useful. Maybe that’s why I didn’t sell many copies of my book.

“Time is valuable. The only shortage we have in our lives is time, and you can’t recapture it. Hopefully, the cell phone can make you more efficient. I’m an engineer, and that’s what engineers do — try to make your life more efficient.”

Cooper says his credo is that technology is worthless if it doesn’t make people’s lives better. “You know,” he says, “a lot of people get wrapped up in technology for the sake of technology. And I think that’s a waste. If you have an invention, make it useful by making people’s lives better.”

That might be why “dumb” phones are making a comeback, and Cooper is hedging his bets. His wife is also an inventor — she was his cofounder of Cellular Business Systems when they married in 1991 — and is the creator of Jitterbug, a dumbphone that’s only used for talk.

“The Jitterbug,” Cooper says, “is a phone for people who want simplicity. They don’t want to have to remember everything. They just wanted to have the ability to talk to somebody else. You just dial, and if no one answers you just hang up.”

The parent company of Jitterbug, which was invented in 2006, has since been taken over by Best Buy.

Cooper himself owns an iPhone and a Galaxy. “I keep up with it because I want to understand the technology,” he says. “I’m always looking for ways to improve things, so I try everything out.” Cooper won 11 more patents over the years since those days at Motorola, and was still active in the wireless technology business until a decade ago.

Never Give Up

Martin Cooper was born in Chicago on December 26, 1928, to Ukrainian Jewish immigrants. His mother, the former Mary Bassovsky, came from a little village called Pavoloch, which Cooper says still exists as a tourist attraction (“because it’s where the Jews used to live”). Her family was driven out by the Cossacks in the aftermath of the 1917 Communist revolution. His father, Arthur Kuperman, came from “a little town called Skvera that you’ve surely never heard of — S-K-V-E-R-A,” Cooper emphasizes for the sake of accuracy. The two immigrated separately to Canada, where Arthur changed his name to Cooper, and where they met and got married. “Even though they came from maybe 60 miles apart in Ukraine,” he says, “they still had to travel many thousands of miles to find each other. Amazing, isn’t it.”

Cooper’s parents tried their hands at various businesses, all of which were unsuccessful. Always working together, they opened a grocery store in Winnipeg that failed, and then they started another store in Ontario. When that didn’t go, the couple immigrated to the United States, buying an existing laundromat in Chicago which they hoped to use to support themselves. But the sellers cheated them — arranging a trial period when they made sure the laundry would be bustling with customers who somehow disappeared as soon as the sale was finalized. Martin and his younger brother were born in Chicago, but the family soon returned to Winnipeg. When Martin was 11, the family headed back to Chicago, where they would make their permanent home — success would finally shine on them.

“My mother would travel to the suburbs of Chicago with a rug under her arm, and she would go door to door offering to sell the rug with weekly payments — 25 cents a week or 50 cents a week,” Cooper recalls. “Little by little she ingratiated herself to these families. The next thing you know she was selling them furniture and clothes, and then my father joined the business. They were like the original Macy’s.”

His parents, similar to many immigrants of that era, brought up their two sons with a Jewish flavor but no real Jewish content, he says.

I had to ask this question: Did he grow up with a phone?

Yes, he tells me. “Our first telephone number was RO-8646, only six digits. We had one phone in the house, of course no one back then had extensions, and very often you had a party line, so several families would be on the same line and you could listen in on other people’s conversations. Those were primitive times.”

Growing up with both his parents constantly at the store, Martin spent a lot of time reading and experimenting.

“My folks were both working my whole life, so I spent a lot of time alone,” he recalls. “I had a great imagination and I read every book that I could get my hands on. From the time I learned how to read I would go to the library, and the librarians couldn’t believe that I could read books of the size I was schlepping off the shelves.

“I guess I always knew I was going to be an engineer because I loved to understand how things work. What is behind the thing? What’s the technology? What’s the science? When I got older, I became a science fiction addict, and I went out of my way to go to a technical high school that had hands-on shops, so I learned a few other skills, too — woodworking, metal forging, machinery, and printing.”

He graduated from the Illinois Institute of Technology in 1950, and from there enlisted in the US Naval Reserves, serving as a submarine officer during the Korean War. His first job was with the Teletype Corporation of Chicago, which made the units that provided remote communications services to media outlets.

Cooper joined Motorola, Inc., in 1954, and earned his master’s degree in electrical engineering from the Illinois Institute of Technology three years later in 1957. At Motorola, he was assigned to the division that was working on inventing portable handheld police radios, which were introduced in Chicago in 1967. By then he had advanced to the position of operations director.

Car-based mobile phones had actually been in limited use since the 1930s. By the early 1970s, they were used with a communications system called the Mobile Telephone Service, which carried signals over the same VHF (very high frequency) that FM radio stations used. Calls were placed not by dialing telephone numbers, but by locking onto specific channels, but the system was unreliable, it was impossible for more than 24 channels to operate on a given network, the phones were prohibitively expensive, waiting lists were up to three years, and they could only be installed in a car because of the necessary power source and antenna.

Motorola’s main competitor was Bell Laboratories, the research division of American Telephone & Telegraph Company. At the time, AT&T had a monopoly on traditional telephone service in the United States, and was working on a new form of mobile communication that it could offer its subscribers. AT&T announced that it had a solution — a “cellular” phone for personal communications.

“I might not be a great Jew,” says Marty, “but I was bar-mitzvahed twice”

Market Shares

In 1970, AT&T — the parent company of Bell Telephone — was not only the world’s largest telecommunications company, but it was also the world’s largest corporation. With a workforce of over a million and an annual revenue equal to $112 billion in today’s money, it was a force to reckon with.

Under the slogan, “One Policy, One System, Universal Service,” AT&T gobbled up one competitor after the next. The Pentagon even declared it a “good” monopoly, saying that its control of the industry was vital for national security. It was even dubbed Ma Bell due to its domination in telecommunications.

Motorola was a fraction of the size. But they had Martin Cooper, an inventor who didn’t mind crashing his own inventions for something better. Just three years before his history-making call on that Manhattan street, he invented the beeper, a small device that allowed users to send a number that would be displayed on a screen, an early form of notification that they wanted to get in touch with the person.

But Cooper’s next invention practically put the beepers out of business.

“The wonderful thing about competition and progress is that you have to keep moving,” Cooper reflects. “You have to keep thinking. Because things change, technology improves, we get smarter with time. That’s why the most important thing a person can do in life is to keep learning.”

He says he learned a valuable lesson when he put his own beeper out of business.

“You have to keep up with the times,” he comments. “If you think that you own the world and you become arrogant, then you will lose the battle. Somebody will come along and do it better. And trust me — I won’t see it in my time, but at some point, Apple is going to find out that there’s somebody smarter than they are, Google is going to find out that they can’t keep up. I love that. You know what that means to me? It means opportunity. It means that anybody who is creative can come up with a new business or a new product, a new idea, and with enough hard work and a little bit of mazel, you can change the world.”

But Cooper needed more than a little mazel for him to succeed on that spring morning. Because the battle for the first cell phone pitted two ideas against each other. He was taking on a company who could spend a boatload of cash on what people really wanted, and they thought they knew what that was.

“It was car phone,” Cooper says, a hint of mockery still in his voice half a century later. “It was a big box that sat in the trunk, with a speaker in the front that you could make phone calls with. You had to be in the car in order to make that call. But I felt the time was ready for personal communications to have a phone that was an extension of the person, not his car.

“AT&T had the monopoly,” he explains. “They had invented the idea of cellular, but when they wanted to implement it, they made a car phone. We thought that was ridiculous. Why do we have to be trapped in our cars to make a phone call?

“Motorola was a small company, but we had a very big share of the market. We created the walkie-talkie that police and the fire department used, and we understood radio communications.” Meanwhile, the government opened the development of the cell phone to competition, which would soon put Motorola ahead of the pack.

When the first automobile was introduced in 1893 at the World Fair in Chicago, the biggest question people had when watching the contraption was, “Where’s the horse?” Cooper, when rolling out the cellphone, got similar questions: “Where are the wires?”

“You know New Yorkers — very blasé and not very friendly,” he said, before hastening to say that he wasn’t talking about me, of course. “We were standing on the street making that first phone call, and even the New Yorkers were amazed at seeing somebody talking on a phone in the middle of the street.”

It took another decade before cordless phones hit the market, and the initial model was so big that Motorola executives named it “The Brick,” even though they advertised it as “weighing only 30 ounces!” It took another six years before the cellphone could finally slip into someone’s pocket.

Phone Freedom

When Motorola first tackled AT&T, a British engineer told Cooper, “You know, in London, we could maybe have 10,000 people who would want a cell phone, but that’s about it. It will never get any bigger than that.”

“A concurring study conducted by Ma Bell also concluded that there will ‘never, ever’ be more than a million mobile phones in the world,” Cooper recalled. AT&T therefore focused on inventing a phone that could travel with the person but would be safely tethered to something.

“And guess what? They were right,” he says, barely containing his laugh. “There were never more than a million car phones, because by the time AT&T came out with the car phone, Motorola came up with this,” he says, reaching under his desk and pulling out the first cell phone prototype.

“Once people discovered the freedom that they had to be able to talk to anybody at any time, it just took off. But it still took 20 years for cell phones to be a big business. Still, we knew that someday, everybody would have their own phone,” he says. “We used to tell a joke that the day would come when you’d be assigned a phone number, and if you didn’t answer the phone, it meant that you died.”

The cellphone survived its birth, infancy and into its young years. Now that it’s turned 50, would middle age slow down its rapid growth?

“Oh no,” Cooper says emphatically. “If you think about the cell phone, it really was a revolution. People in the world today cannot live without their cell phones, and the revolution is just starting. Because once you connect people, you can change the world. Because not only can people talk, they can collaborate, put their minds together, create things to increase productivity.”

Cooper is not yet done reimagining telecommunications. He marvels at how smartphones replaced dumbphones and he wonders what will be next.

“Back in 1973, the digital camera had not been invented, the internet didn’t exist, and there were no personal computers,” he recalled. “So it’s still a shock to me that they’ve managed to put a phone, a computer and a camera into this little tiny box. I believe that we’re still in the early stage of the cell phone. The cell phone of the future is going to be very different. It’s going to be distributed somewhere on your body. You may have a device in your ear — or maybe even under your skin — that will act as the audio phone. You will have some other device in your glasses so that you can see a screen and you can do augmented reality.

“We’re only just beginning,” he affirms. “In 20 years from now, you won’t be able to recognize what used to be a cell phone.”

Since you can’t have a good Jewish conversation without a good joke, I ask him to tell me his favorite joke about the cell phone.

“My jokes are pretty old,” he apologizes in advance. He’s right. You can date yourself if you laugh at this: “In the early days, in order to get a cell phone you had to really know somebody. In New York, the maximum number of phones allowed was 1,000. So you could imagine that if you were a senator in Washington, you would pull all the strings to get a new phone. One senator got his phone, and he was so proud that he called up a colleague and said, ‘George, I’m calling from a cell phone.’ George responds, “Yes, I also have a cell phone.” The senator interrupts, ‘Hold on a second. My other cell phone is ringing.’ ”

He waits a second to gauge my reaction. It’s an old joke, which I first heard in camp 30 years ago.

“Okay, that’s a lousy joke,” he concedes. “Zei gezunt.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 973)

Oops! We could not locate your form.