Waiting with Yaakov

| July 18, 2023This is why I’m quite strict about using the term “specialized needs” instead of “special needs”

Igot yelled at a few weeks ago in shul. I was startled, both because I try hard not to do things that would warrant such a reaction and because the people I daven with aren’t the kind of people who yell at fellow congregants.

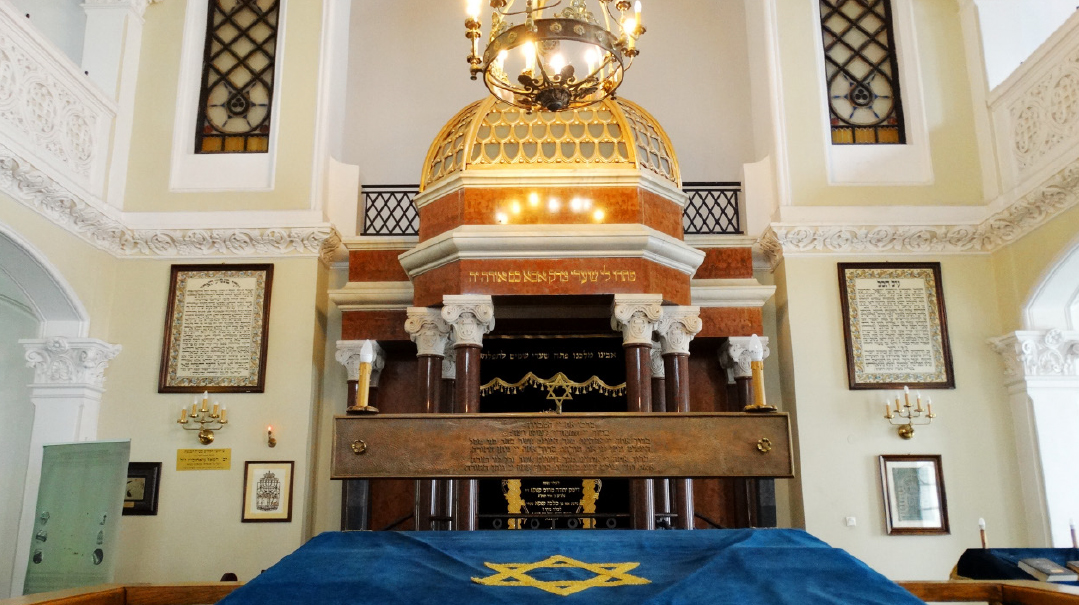

Our shul is a beautiful building, but it does have one design flaw: a particularly narrow entrance and exit that hinders traffic flow. This isn’t an issue during the week; depending on whether davening is starting or ending, people are usually walking in the same direction, and those who aren’t are patient. The issue comes up primarily on Shabbos afternoon, when the mispallelim of the early Minchah minyan want to leave, and the arrivals for the second Minchah want to go to their seats.

I found myself in just such a traffic jam a few weeks ago. I stood outside the sanctuary conversing with a young man named Yaakov as we both waited for a break in the crowd. Some people tried snaking their way in through the outgoing crowd, but I did not, because my mother taught me to wait my turn and to always allow people coming out of a room or train or elevator to exit before I try to enter.

The second reason I didn’t push my way in is because I was waiting with Yaakov.

And Yaakov uses a wheelchair. Which is why I got yelled at.

IN my role as director of clinical innovation at Makor Care and Services Network in Brooklyn, New York, I’ve spoken and written extensively about the importance of inclusion of people with specialized needs in our community’s schools, shuls, and workplaces, advocating for greater acceptance of individual differences at every level.

Concurrently, when working with individuals with intellectual disabilities in classes at Makor’s College Experience Program, in Makor’s residences and community programs, or in my private practice, I try teaching those with intellectual differences how to achieve that acceptance and live up to the expectations and responsibilities community membership requires.

My varied roles have made me something of a “go-to” person for everything disability-related. Which I guess is why the bystander who saw us waiting for the crowd to pass so we could get to our seats was annoyed that I wasn’t standing up for Yaakov.

“Why are you just waiting there?! Get them to clear the way for him!” he berated me in a tone and volume that can best be described as well-intentioned venom.

At first I was taken aback, but once I regained my composure, I reflected on what had just happened.

Yes, those ambulatory shul members who were eagerly rushing to their seats were able to dance their way through the crowd using an agility that Yaakov, because of his cerebral palsy, does not have. But the reason Yaakov was patiently waiting to enter is not because other people were ignoring him (even if they were) or because of his own physical impairments (which he has), but rather because his mother, like mine, had taught him the same lesson in basic courtesy: First you let people exit, and then you enter.

In other words, Yaakov was not left waiting because other people were acting inappropriately; rather he was waiting because he was acting appropriately.

A little bit after the incident, the person who yelled at me apologized for his verbal onslaught.

“It just upsets me so much when people don’t help people with disabilities,” he said.

Truth be told, that upsets me, too. But only when people with disabilities need help.

Of course, there are times when people with specialized needs require accommodations. The fact that all the sinks in our shul are wheelchair accessible or that scattered pews throughout the sanctuary are cut short so people in wheelchairs can sit throughout the room are ways the shul conveys to Yaakov and others with similar challenges that they are welcome. There are no “special sinks” and there is no “special wheelchair section.”

Same for other challenges that make it legitimately difficult for people to wait their turn; I appreciate fast-passes at the amusement park so people with autism need not wait on line, and I appreciate the shadow programs at our shul’s youth groups so kids who need extra support can join their peers Shabbos morning.

But it is equally important to not view all people with disabilities as globally helpless because of their specific challenges, and not to allow people with disabilities to believe themselves entitled to special treatment when their challenges don’t warrant that support.

This is why I’m quite strict about using the term “specialized needs” instead of “special needs.” People with cerebral palsy or Down syndrome or autism or Williams syndrome might need teachers with specialized training or doctors specifically qualified to address the unique medical challenges associated with these conditions. But the need for a specialist’s services does not make the education or health of a person any more “special” than the education or health of anyone else.

Furthermore, the community should not view their efforts to ensure that everyone is able to get an education or have their medical needs met as doing something “special.” Sometimes the very act of labeling someone’s needs as “special” separates them from the community rather than including them.

So, too, when it comes to behavior: Just as there is a real cost to not giving someone the education or medical care they need to thrive, there is a cost to not teaching people with intellectual and developmental disabilities how to behave appropriately in society, even when that tolerance is given with the best of intentions. At times tolerating inappropriate behaviors only adds to a person’s disability. Determining which behaviors are part of a person’s diagnosis and which are due to a history of misguided chesed can be difficult, and acting on this difference must be done thoughtfully.

Let me end with three pieces of concrete advice that I hope will be helpful in building a more appropriately inclusive community:

If you see a child with specialized needs acting in a manner that would typically have you say something, first check with the child’s parents if it is okay to do so, and if it is, would they prefer to say something or should you?

Speak calmly and with sincere understanding — “Is your child’s humming in shul part of his diagnosis, or can I ask him to please stop?” — and you’ll be surprised how many parents are appreciative when their children are held to typical standards. For both the parents’ sake and the child’s inclusion, communicating your expectations is better than having people tolerate disruptive behaviors only to later tell the parents their child is no longer welcome.

The same holds true for adults. I recently spoke to a business owner who let an employee with specialized needs go.

He seemed genuinely disheartened about it, so I asked him what happened.

“He was just too social in the office,” he said. “We loved having him around, but it was getting in the way of our work.”

When I asked if he had discussed his workplace habits with his former employee, he said, “Oh, no, his friendliness is a strength! I wouldn’t want him to change!”

What could have been a lesson in professionalism and a steady job for a capable employee instead became a failed chesed project. That’s what tolerance over-teaching often leads to.

When you see a parent or group home staff member try to teach someone with specialized needs to behave socially appropriately, don’t interject and say, “No, it’s okay!”

Too often, bochurim approach me and say, “We love spending time with Reuven, but can you please tell him not to interrupt us while we’re learning in the beis medrash?”

“I can, but it would be so much more powerful if the next time he interrupts, you tell him you’ll speak later instead of stopping your learning for a conversation with him,” I’ll advise.

But the bochurim often reply, “Oh, no, we don’t want to hurt his feelings.”

When approached with sensitivity, teaching someone appropriate behaviors will not hurt their feelings, and it’s necessary to help them grow into functional and welcomed members of the community. When I tell a Makor guy, “You know, I don’t think they really appreciated you interrupting their learning,” the response is usually some variation of, “But they let me!” I then have to explain that people tend to tolerate that sort of thing once, but quickly turn away when they see you coming next time.

As nice as it may seem to allow a person with specialized needs to behave inappropriately in the name of tolerance, or as nice as it may seem to undermine a lesson in socially appropriate behavior by saying, “No, it’s okay!” don’t follow that urge. As we tell the Makor guys, “Sometimes when people are nice, it isn’t so nice.”

If you see someone with specialized needs behaving appropriately, let them.

In fact, show them the natural rewards of appropriate behavior by treating them just like everyone else. If you’re the gabbai and you see someone with Down syndrome davening nicely, offer him an aliyah. If you’re a business owner, offer someone a job, and train them to do it well. (You can even call Makor’s Supported Employment office; we have a lot of qualified and talented people just waiting for opportunities.) If you see someone in a wheelchair patiently waiting his turn to enter a room, strike up a conversation while you wait together.

And if someone is already waiting with the person, don’t yell at him.

Stephen Glicksman, PhD, is a licensed developmental psychologist. He serves as director of clinical innovation at Makor Care and Services Network as well as director of its research and education branch, the Makor Institute.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Jr., Issue 970)

Oops! We could not locate your form.