“Wait… You Live Where?”

| December 26, 2023The beauty, benefits, and challenges of living way out of town

I’ve only ever lived out of town. I grew up in Des Moines, Iowa (yes, really), and became frum in the wonderfully warm community in St. Louis, Missouri. The first time I came to Cleveland, I remember standing on South Taylor Road, in awe that I was in front of a kosher grocery store, next to a frum clothing store, and across from the Torah day school my children would one day attend.

Though I love traveling to bigger Jewish cities — the first time I visited Brooklyn, I thought I was in some sort of frum wonderland — my heart will always be with small out-of-town communities. You may not get the perks of numerous frum amenities there, but what you will find is plenty of teamwork, idealism, passion, and warmth.

Portland, Oregon

100 shomer Shabbos families

Two shuls, two mikvaos

An average home of 2,000 square feet goes for around $600K

Congregation Kesser Israel is the oldest Orthodox shul in Oregon

About 40,000 Jews in Portland total, with Jewish history going back to 1849

Eleanor Warshaw grew up in Portland, Oregon, but spent much of her childhood fantasizing about leaving it. As a child, she visited extended family in Los Angeles often and was always sad when it came time to leave. “My childhood in Portland was wonderful, but I was desperate for more friends and more opportunities,” she shares.

Since there’s no Jewish high school in Portland, Eleanor eventually ended up at Bruriah High School in New Jersey. After seminary, she attended Stern College and then met her husband, who was studying in Shor Yoshuv. The first few years of marriage, they lived in Far Rockaway, and Eleanor began nursing school at Maimonides in Boro Park.

“Finally, I was your typical frum girl,” she chuckles. “I was living the dream that I’d fantasized about as a teenager — operating in the thick of the frum world. But wildly enough, I began to realize that I didn’t really like it. I couldn’t find my niche.”

Both she and her husband, an Israeli whose family had moved to Baltimore when he was a teen, had a desire to live in a community where they could make a difference. So they decided to move to Portland.

“When people hear about us living here, they sometimes ask, ‘Why would you do that to yourself?’ As if I’m hurting myself,” says Eleanor. “But some people get it, people who understand the idea of fresh air and a calm, happy lifestyle. I wish everyone understood the value of what it’s like seeing so many different types of Jews in shul — young and old, religious, semi-religious, becoming religious, or not. Everyone is together, everyone is working literally as a team, making this micro-community go. It’s incredible.”

The phrase “kol Yisrael areivem zeh l’zeh — all of Israel is responsible for one another,” is a daily lived experience in smaller communities. “Really, this community only works with teamwork,” Eleanor says. “You can stay anonymous in a larger community, but here… you can’t. You’re going to end up on a board or leading a committee. Because if you don’t get it done, it’s not happening. You can’t come to a small community and sit back and relax.”

Eleanor’s father was involved with building the mikveh in Portland. “I grew up with the story of how when they needed water to start it, they drove to Mount Hood to get snow. Imagine — a group of Jewish men with buckets going to the mountain, filling the buckets with snow to bring back to be able to start the mikveh.”

With the absence of an Amazing Savings or Gourmet Glatt, what does preparing for Yom Tov look like? “It looks like teamwork,” Eleanor shares. “Four or five months before Pesach, my WhatsApp is exploding with people who want to split bulk items or are trying to figure out where to find a particular item. We all help each other out.”

Chicken, meat, and dairy items can be found at some local stores, and Portlanders place bulk orders to get a wider variety of kosher meat; other niche kosher products can be ordered online. “You do have to plan ahead sometimes,” says Eleanor. “But there’s never a recipe from a kosher cookbook that I can’t make.”

Another asset of a small community is that it’s not big enough to have cliques. “When there are only five girls in your class, everyone becomes your type.” On the flipside, if there’s a class of four or five kids and one moves away, it’s acutely felt.

“When I came back to Portland as an adult, I realized how privileged I had been growing up here. I took for granted how innocently kids are raised,” said Eleanor. “There’s no concept of clothing brands, of what’s in and what’s out. There’s none of that. What we have here is a little bit of magic.”

Leanne Dall also grew up in Portland, the daughter of South African parents who ran a traditional home. The Kollel and NCSY came to Portland when she was a senior in high school, and that catapulted her on a journey to Torah observance.

“My husband and I lived in Toronto after we got married, but the idea of moving back to Portland always simmered in the back of my mind,” she says. “I felt like the families who came to reignite the Portland community needed support. If I, who grew up there and became frum because of them, wasn’t going to do it, who was?”

She and her husband, a South African, decided to try living in Portland for two years. “Ten years later, we’re still here,” Leanne quips.

Leanne is responsible for setting up meal trains for frum families in Portland. Once a friend texted her, saying that she was having a busy week — did she really need to sign up to make a meal? “I told her, ‘Yes, you actually do! If you don’t, the meal chain won’t get filled!’” While that communal achrayus can be a challenge, it’s also one of Leanne’s favorite parts of living in Portland. “You know that you’re important.”

There’s one street in Portland called “Rabbi Row” where most of the frum families have ended up living, and they host an annual Purim block party. “Every year, it’s a huge thing. We all chip in and bring in petting goats and ponies. Every non-Jewish neighbor is sent out a notice a week in advance. It’s an incredible, amazing, spirited experience, where we’re all celebrating together.”

What Leanne would tell people who are considering moving out of town is that it doesn’t have to be a lifelong commitment. “Even the couples who stay for just a short while, maybe three to five years, can really gain. The community gains, and they gain, both personally and professionally. You have a lot more opportunities to take on leadership roles, so it’s the biggest résumé builder.”

Norfolk, Virginia

150-200 families

Founded in 1946, B’nai Israel Congregation is the oldest continuously operating Orthodox synagogue in the region.

Close to jobs and transit, homes within the eiruv are in the

$400-600KsThere are two elementary schools, a middle school, a boys’ high school, and a girls’ high school.

Rabbi Gershon and Sara Litt spent the first few years of their marriage living in Monsey, relocated to St. Louis (where Rabbi Litt worked for Aish HaTorah, and where I experienced my first Shabbos ever, in their home) and eventually landed in Norfolk, Virginia, where Rabbi Litt accepted a position in the kollel. Eighteen years later, they’re still there.

“The slogan of Norfolk is: ‘Move to Norfolk, make a difference,’ and either you make a difference, or there is no difference,” says Rabbi Litt.

When the Litts first moved to Norfolk, the day camp choices were very limited. “There were a few options, but none of them were great for members of our shul,” says Rabbi Litt. “So… I started a camp. That’s the kind of the mentality you need when you move into a small community — if something doesn’t exist, you must create it.” He also started a boy scout troop. “We called it Troop 613,” Rabbi Litt remembers.

Living in a community with less infrastructure means learning to live with fewer amenities, but it also means living with less competition. “There’s no keeping up with the Schwartzes because there are only two Schwartzes,” Rabbi Litt jokes.

There’s no dedicated kosher store in Norfolk. Meat orders come in from Baltimore once a month. “You can get specialty kosher items sometimes in the regular stores, but you can’t rely on it,” Sara says. There’s a bit of a catch-22 because the community doesn’t buy from the local store enough for the store to consistently stock kosher items, and the store can’t reliably stock the items if the community doesn’t regularly buy them there. People make do with what they can get.

“For the community we have, we have enough options. Of course, we would love a pizza shop, a fleishig restaurant, a cafe, but the benefits of living here are a worthwhile trade-off,” said Rabbi Litt.

Another challenge is meeting the needs of a diverse population. Combining kollel families with baalei teshuvah and long-standing locals, it can be difficult to find a standard that everyone will be okay with. “There’s only one shul in town and it’s Ashkenazi, but some members are Sephardi. When you’re in a small community, you have to figure out how to live together, pray together, and give each other the room to be unique within one community,” says Rabbi Litt.

Since there’s only one school, “there’s no concern if your kid is going to get in or not,” says Sara. “The school is small enough to be able to cater to the unique needs of the student body. This might be the most important reason to consider moving to a community like ours. The rebbi or morah is able to focus on each individual child, not just the class as a whole. Each child matters and gets what they need.”

People considering moving to Norfolk sometimes wonder, “what is the future of my children going to look like?”

“Your kids will become leaders,” Sara says. “The kids growing up here develop incredible middos, and they go on to the top yeshivahs and seminaries in the world.”

Rabbi Litt takes a different approach to the question: “I want to challenge the assumption that there’s a right or wrong place to live as a frum Jew,” he says. “Maybe we can reframe the perspective of why we think that it’s so important to live in the cocoon of larger cities. What’s there is beautiful, and the communities are incredible — when we lived in Monsey, we certainly appreciated what was there, and appreciated living in a society where everyone around us was like us — but maybe there’s a message here that people can ask themselves: What, at the end of the day, are the priorities they want to set for their family? How best can their children learn about acheinu kol Beis Yisrael and ahavas Yisrael?

“I’m privileged to live in a community where there is diversity in frum life, where you can learn from each other, grow with each other, and together make a difference in other Jews’ lives. How many Jews can really say that?”

Cincinnati, Ohio

350 families

Cincinnati features all of the standard Jewish community amenities, an eiruv, a kollel, two mikvaos, five kosher eateries, kosher groceries, and a state-of-the-art Jewish Community Center.

Housing is extremely affordable, with a 2,500-square foot 4-bedroom home on a half-acre lot for less than $350K and property taxes less than $10,000/year.

The kever of the Gadol Rabbi Eliezer (Leizer) Silver is in Cincinnati

Shanny Katzman has lived in Cincinnati for around 12 years. The Katzmans started off their married life in Baltimore, before moving to Columbus, Ohio, where Shanny’s husband learned in kollel for five years. When it came time to transition out of full-time learning, he started looking for actuary jobs.

“He applied for positions in a lot of different communities — big ones, small ones — but when a job offer came up in Cincinnati, only an hour and a half away from Columbus, it was an easy choice,” says Shanny. They were comfortable with the size of Cincinnati because they’re originally from smaller communities — Shanny is from San Antonio, Texas and her husband is from Omaha, Nebraska.

Cincinnati’s Jewish community is nestled in a suburban area that feels tucked away from the bustle of the city. “We have a lot of woods around us and there are always deer,” says Shanny. “One of the things people notice when they come here is that there aren’t sidewalks or streetlights in most of the neighborhood.”

Most of the infrastructure of the city is within a one-mile block square. “With the exception of two schools and the JCC, everything is here: The kollel, the mikveh, all the shuls, most of the schools. Walking from one side of the community to the other would be, at the most, around a half hour.” While Shanny enjoys the tranquil environment, she notes that it’s just a ten- to 15-minute drive to get to the city.

“I used to say Cincinnati is the secret of the Midwest,” says Shanny. “It’s this quaint, frum, little community in the middle of nowhere where everybody coexists nicely, and anybody who knew about it was thrilled to be in on the secret.”

These days, however, the secret is out. Cincinnati has recently experienced a lot of growth. As the community has grown, so have the options of where to send your child. In addition to the Cincinnati Hebrew Day School (CHDS), one of the oldest Jewish day schools in America outside of New York, the community has gained a new mesivta, a Bais Yaakov High School, and a Montessori day school, all opening their doors within the past ten years.

While the school choices have increased, class sizes remain moderate and manageable, sometimes in the single digits. Shanny’s girls are very appreciative not only of the smaller class sizes, but of the relationships they’re able to form with their teachers and the school administration. “They feel their teachers really know them,” Shanny says.

Though Cincinnati is a smaller community, there’s plenty of opportunities to be busy. “If you like that fast-paced always-having-something-to-do feeling, you can still have that here in Cincinnati because you can host this, you can host that,” Shanny says. “But you could also choose a slower pace of life and nobody is going to judge you for it. It’s the best of both worlds.”

In terms of conveniences, most basic needs are easily met. There is a basement salon for sheitels, as well as many other options for a wash and set. In terms of clothing shopping, the Jewish world has shifted enough to online shopping that it’s not a hurdle like it was years ago. While there isn’t an established store for women’s or men’s clothing, there is a store that sells uniforms and accessories like socks, headbands, white shirts, suit pants, and jackets for children. “For our son’s bar mitzvah, my husband drove up to Cleveland on a Sunday with our son to check off the big items like tefillin, suits, and a hat,” says Shanny.

Part of preparing for Yom Tov can mean taking a road trip. It takes five hours or less to drive to larger Midwestern communities like Cleveland, Detroit, or Chicago. “Pop-up stores with overstock from the East Coast also come from time to time, before Yom Tov, and people love to take advantage of that,” says Shanny. “I’m lucky to be able to benefit from Moadim L’Simcha, where I can order meat, poultry, and other Yom Tov necessities twice a year at a subsidized price because I’m in chinuch.”

For weekly grocery shopping, the local grocery store chain, Kroger, stocks enough kosher products, meat, and chalav Yisrael products to work for Shanny’s shopping needs. “It’s not the Grove, or Seasons, but it works for me,” she says. Many people place orders from Kosher West in Lakewood for more specific kosher items or brands that aren’t currently available in Cincinnati. “A whole bunch of boxes are delivered at a designated location, and people pick up their food from there,” says Shanny.

What feels distinctly Cincinnati to Shanny is the close-knit social life. “On any given Sunday or even weekday, you can find yourself going to a Shacharis with a breakfast provided, then to a baseball game where two shuls are playing against each other, and then two hours later, you’re changing to attend a midday vort, and then there might be a town hall meeting that night or something. And at all those events, you’ll see roughly the same people.”

One challenge of that dynamic is that about 50 percent of the frum community is in chinuch. “We’re teaching and raising everybody’s kids,” says Shanny. “It’s a huge brachah in so many ways, but when you are your friend’s child’s teacher and you need to talk sensitively about something, it can be tricky.”

Despite that challenge, there is a beautiful sense of achdus in the Cincinnati community. On Simchas Torah, Shanny’s shul alternates yearly with the shul across the street to walk over and dance two hakafos with each other; two different congregations embracing in one shul! “At any given point in the year, my husband will make himself available to lein at all three shuls, and is also grabbed to be a surrogate Kohein for duchaning at the Chabad shul when necessary,” Shanny says.

The community closeness doesn’t stop with the frum community, but extends to the local police and fire department. “Every Thanksgiving, we all gather at the fire and police station and bring them a lot of yummy food from the community to show our hakaras hatov.”

As with any community that experienced a lot of growth in a short period of time, there have been growing pains, but at the end of the day, Shanny wouldn’t want to live anywhere else.

WANT TO MOVE OUT OF TOWN?

START HERE.

Since 2008, the Orthodox Union has helped assist thousands of families in finding the right community for them through its Savitsky Relocation Fair.

The next fair, which is virtual, will be held b’ezras Hashem on March 3, 2024, but if you don’t want to wait for that, you can visit their Communities website and peruse the extensive list of possible communities. You’ll find information about general home prices, number of shuls, schools, and mikvaos, as well as other pertinent information.

While lower home prices and vouchers can make a move out of town seem extremely appealing, families should also do their due diligence and consider the hashkafic makeup of the community, the job market, the schools, and the general culture. Is it more modern Orthodox? More yeshivish? “You want to set yourself up for success,” says Rebbetzin Judi Steinig, Senior Director of Community Projects and Partnerships and Coordinator of the OU Communal Growth Initiative.

Knowing yourself is an important part of the process. For example, one person might find out-of-town living relaxing and refreshingly calm — and another person might find that same calmness incredibly boring. “It really depends on your personality and the personality of the people in the family,” Rebbetzin Steinig says.

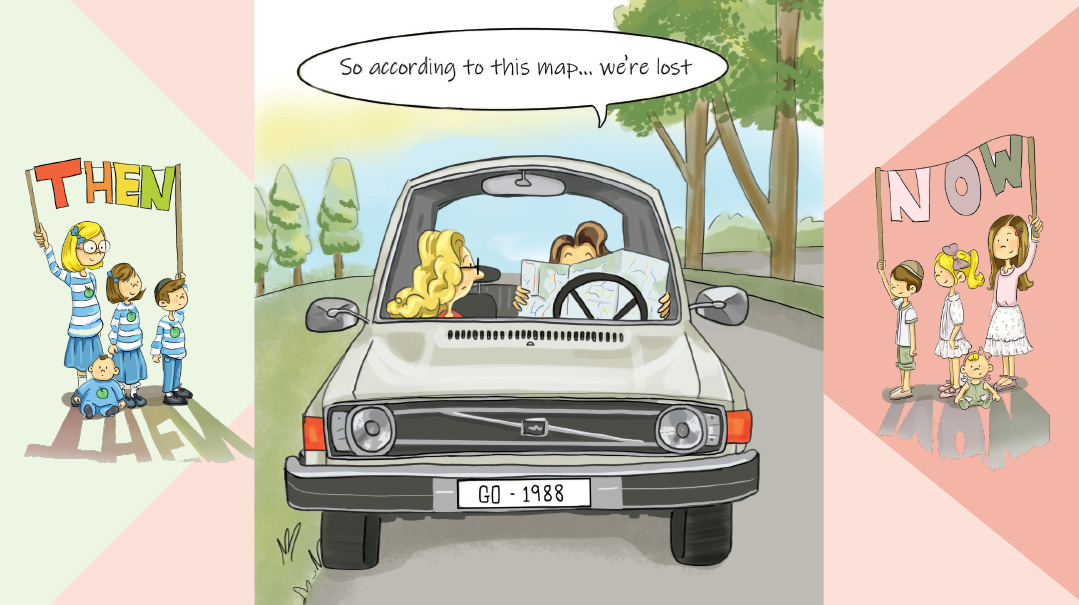

Today, with email, chats, and online shopping, living out of town doesn’t mean being totally disconnected from the larger Jewish community. In many ways, the world is much smaller than it was 20 years ago, when people moving out of town really had to be pioneers. “These days, there are much more amenities out there in smaller communities, and that obviously makes it more attractive to new families.”

If you’re seriously considering a big move, be sure to speak with a representative from whatever community you’re thinking about relocating to, and ask focused questions about the makeup of the community. View it like a shidduch, because, in a way, it is.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 874)

Oops! We could not locate your form.