Voice Over

| April 3, 2023Child star Bentzy Kletzkin finds advice for life and the upheaval just waiting to happen when his voice changes

Photos: Itzik Belinsky, Yehushua Fruchter, Mendy Hachtman, Gilad Tidhar

Can the wonder remain once the kid is gone? If you’ve ever visited a frum community in Israel, chances are the familiar song “Shreit’shet Yiddelach Gutt Shabbos” ushered in Shabbos over the neighborhood loudspeakers, featuring the timeless voice of wunderkind Aharon Halevi. But “Aharon Halevi” recorded that song on the first L’Chaim Tisch album over 20 years ago, and he’s no longer the mysterious child whose rich voice resonated on airwaves and in so many Jewish homes.

His real name is Motty Vizel, and after his voice changed and he left the music studio for the beis medrash, he eventually reemerged as a popular adult vocalist. Today he’s even a bit of a mentor to a younger version of himself, 13-year-old Bentzy Kletzkin — the self-taught pianist and guitarist with the golden voice who was catapulted to the stage when he was just ten. The two have made several recordings together (including “Vehoser Mimeni” and Rabbi Dovid Hofstedter’s “Maoz Tzur”), and we couldn’t resist bringing them together for our own personal concert, with Benzty bent over the piano as he sings harmony to Motty’s “Gutt Shabbos” classic.

By the time you read this, Bentzy will actually no longer be a “wunderkind,” but a “wunderteen,” as he dons the chassidishe levush of a bar mitzvah bochur. But he still has those star qualities discovered a little over two years ago: an impressively wide range, absolute control over his vocal chords, and a confident stage presence coupled with a youthful innocence that wins the hearts of any audience.

“My first performance was when I was ten and a half,” Bentzy says. “It was about two weeks before Chanukah, and I’d joined the Chassidimlach boys choir, directed by Yanky Levinger. He wanted to test my range, so he asked me to sing a solo, and I guess he realized there was something there. We were scheduled to perform at a private event together with Malchus Choir, and Yanky Levinger called Pinchas Bichler, the director, and told him to give me a solo. It was a section of Avraham Fried’s Aderaba, and it was the first time that I stepped away from the choir to sing alone.”

It didn’t take long before the phones began to ring. That very night, people had seen the concert clip and reached out to Bichler and Levinger to book the child soloist who’d hit the high notes so effortlessly. Soon Bentzy Kletzkin was in the spotlight.

After all these years, the songs Motty Vizel/Aharon Halevi made popular are still being sung — “Gut Shabbos” and “Kah Echsof” from L’Chaim Tisch, “Aneinu Borei Olam” and “Anavim” from Mona Rosenblum’s Philharmona series are just a few. But unlike Bentzy, who’s up on stage, front and center, as a child Motty was a hidden celebrity. He never performed in public — his singing was limited to studio recordings for which he used an assumed name — and even his close friends didn’t know that their classmate from cheder was the famous soloist Aharon Halevi.

“People don’t associate any of these songs with me,” Motty says. “They’ve been sung for so many years, all over, but most people don’t have any idea that it was me singing back then.”

After his voice changed, Motty — a Dushinsky chassid from Bnei Brak whose full name is Mordechai Aharon HaLevi Vizel — exited the professional music world for a long stretch. He started singing again after his wedding. His first foray in his round two was as a vocalist for the Malchus Choir. Then he began to take some jobs as a wedding singer. It was a way to make a little parnassah, but, he says, it was grueling. “In a sense, my success as a kid was working against me. People hired me expecting to see the talents and intensity of Aharon Halevi, but instead they got a rookie singer. My wunderkind voice was gone, and I hadn’t fully grown into my new capabilities. I was pretty raw.”

As far as he is concerned, Aharon and Motty are two separate personas. “Aharon Halevi was its own brand,” says Motty, who is 33 today and lives with his family in Elad. “When I re-entered the music world, that brand was gone. It wasn’t a success I could ride on.”

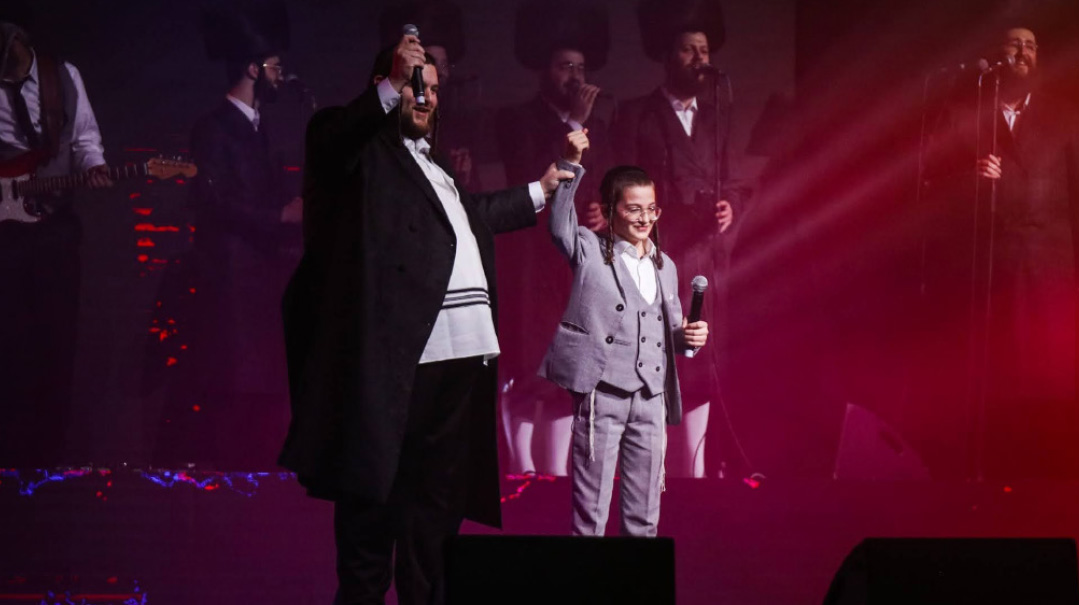

Motty and Bentzy are used to sharing the stage together, and this Yamim Noraim production with Malchus Choir opened hearts in a whole new way

Singing in Secret

Once Motty’s voice changed, his musical career basically petered out. “Part of being a child star is knowing you have an expiration date,” he says. Bentzy Kletzkin nods in agreement, but his expression says, “Na, this will never happen to me.”

“Every artist faces a ticking clock, a certain knowledge that his talent will fade at some point — but with child singers it’s pretty black and white,” Motty explains. “By age 16, a boy’s voice is usually gone. It happened to me at age 15 and a half. The entire career of ‘Aharon Halevi’ lasted three and a half years, beginning when I was 12. It was a short window, and the producers really maximized it. I sang on dozens of albums, about 50 songs. Still, I sometimes feel that at I could have recorded more.”

Bentzy says he’s not worried, even if and when his voice changes. “I plan to continue to perform after my bar mitzvah b’ezras Hashem, and once my voice changes, I hope to stay involved in the music world — playing rather than singing. I don’t think I’ll feel like I’m missing out, because in all honesty, creating music sometimes appeals to me even more than singing. Once I’m in yeshivah, I’ll be happy to play, compose and make musical arrangements, but mostly, I think I’ll be happy just being a regular bochur.”

Looking back, would Motty have liked the spotlight as well? “In retrospect, I realize that at that point in my life, it wouldn’t have been good for me to be involved with stages and audiences,” he says. “A kid has to be very strong to emerge from all the public exposure with a healthy sense of self, and my father didn’t want me to go through that struggle. He encouraged me to sing and use my gifts — he definitely saw singing as a mandate and a lofty goal — but preferred to keep it behind the scenes.

“And because of that,” he continues, “it was really a bit ironic. I remember that a bus passed right by me with an ad about a new disc ‘featuring wunderkind Aharon Halevi.’ I smile to myself, but couldn’t really share the reason for my smile with anyone.”

It wasn’t until shiur beis in yeshivah ketanah that Motty’s secret was out.

“The booklet that came with a disc mentioned my brother-in-law Zevi Fleigman, who was my agent, so someone figured out that Aharon Halevi was actually me. But I didn’t really mind at that point, because I knew that my time in the music industry was coming to an end. A very short time later, my voice changed, which was fine for me because I could finally focus full-time on my learning.”

Bentzy confirms that even in the music world, the identity of Aharon Halevi isn’t universally known. “The truth is that I didn’t know that Aharon Halevi was Motty. In my house we still listen to L’chaim Tisch on Erev Shabbos, but I never made the connection. Yanky Levinger told me — he just assumed I knew — and I couldn’t believe it….”

“Pinchas Bichler gave the sign, and I stepped away from the choir to sing alone.” Once the industry got wind of Bentzy, the spotlight was his

Then and Now

Motty, whose career was limited to closed rooms and occasional internal events of the Dushinski mosdos, had a pretty standard childhood. “My life as a boy and as a yeshivah bochur was pretty regular,” he says. “I didn’t feel unusual at all.”

Bentzy, who chose to become a stage presence, is experiencing a different kind of childhood. Music has always been part of his family culture; he belongs to a large Yerushalmi family with many talented and well-known musicians. His father, Reb Binyamin Kletzkin, is a well-known clarinetist and wedding singer, and his grandfather Reb Bentzion Kletzkin a”h was a chazzan and musician who brought joy to thousands of homes.

But he’s charting his own path, performing across the world in grand venues with enormous orchestras and videographers capturing every note. Performances are demanding in so many areas, and for a young boy, life as a singer can be overwhelming — whether it’s the numerous rehearsals, the flights abroad, or juggling schoolwork with weddings and dinners.

He claims, though, that he’s still a typical cheder boy. “I don’t feel different from my friends,” he says. “But the fact that so many people know me and have heard me sing does affect my social standing. I know there are kids who want to be friends with me because I’m famous. But there are always the real friends, the ones who like you for yourself. Sometimes it’s hard to figure it all out.”

Today’s wunderkinds can’t realistically keep a low profile. Virtually every performance is recorded and posted online, and almost every popular song has some kind of clip along with it.

The role is also more demanding than ever. “It’s not enough to have a nice voice anymore,” says Motty. “You need a huge skill set. You need to perform flawlessly for an audience, and everywhere you go you have to put up the perfect appearance with the perfect behavior — because everyone recognizes you. On the other hand, living in the shadows had its own challenges. It wasn’t easy for me to live a double life, to hide my secret studio time from my closest friends.”

On the plus side, Motty points out, the work he did as a child had real staying power. “Once an album came out, you’d listen to it over and over — at home, in the car, on trips. Those songs lasted and lasted. Today’s singers release singles that are super-popular for a short while — and then fade away and get replaced by others. The turnover is very high, people have less attention and patience, and they just skip from album to album. Songs don’t have a long shelf life today — even high-quality songs. People get bored so quickly, they’re always looking for something new.”

As Long as

A good child vocalist — called a “yeled hapele” in Hebrew — is a sought-after commodity in the chassidic music world. These kids contribute unique musical timbre that adults can’t generally duplicate, and there is something special about their innocence and heartfelt singing.

The children in the albums of our youth remain frozen in our consciousness as children, but in the real world, their careers are rather short before they fizzle out. A rare few, like Motty Vizel, re-emerge for a second round in the music world after their voices change — singers like Ari Goldwag, Mordechai Shapiro, and even Avraham Fried are a few names that come to mind — but for the most part, these kids know that once their vocal cords thicken, the show is over. How do impressionable teens at the height of their fame deal with the forced fadeout? Is there a healthy way to become anonymous after years in the spotlight?

“I’m not afraid of the day after,” Bentzy Kletzkin says with an air of 13-year-old confidence. “B’ezras Hashem, I’ll continue to sing as long as my voice will allow. The minute it stops, I’ll be able to focus on playing. I’m actually planning to release a song I composed and arranged myself. People are already telling me, ‘Brace yourself, because you’re going to miss these days.’ Some of them, including my manager, Yanky Levinger, tell me, ‘Record as much as possible now, so you won’t regret that you lost your chance after it’s too late.’ The truth is, I’m not such a studio person. I happen to love the action and energy of singing live and being onstage.”

But his alter ego, Motty Vizel, would encourage him to stick it out in the studio. “The same thing happened to me,” he says. “People in the industry wanted me to record more, but I basically told them I’d had enough. Today, though, I regret every song that I didn’t record then and I look for any memento I can find from that time. Aharon Halevi is a figure that was, but is no longer. So Bentzy, don’t forego this gift that you have. Grab what you can, record as long as you can, as long as you have your voice.”

If he’s looking for mementos, Motty says there still is recorded material from Aharon Halevi that was never released. It was a song recorded with Mona Rosenblum. “Maybe one day it will be released,” he muses. “That would really be a blast from the past.”

Fallen Stars

All this talk about voices changing and careers fading isn’t lost on Bentzy. He turns to Motty and asks, “Is it true that your voice changed in one day? I heard once that it just caught you by surprise, and it was all over in one day.”

Motty gives what he hopes is a comforting smile. “It didn’t happen in one day. What happened is that we were working on a new L’Chaim Tisch album, recording the Vizhnitzer Menuchah Vesimchah, and I realized that it just wasn’t going. It wasn’t a crisis, my voice didn’t disappear entirely or anything dramatic like that — but I wasn’t able to produce the sounds that used to come so easily to me. It’s like, you suddenly feel something shift in your world. You realize that you had something, and now it’s not there anymore.

“Of course, my friends and family were supportive and encouraging. They told me that it would come back, that soon enough I’d be singing again. But the wider public isn’t so forgiving. I would get comments like, ‘You used to have a really nice voice, you know?’ ”

He smiles in resignation. “You could be the biggest hit, the most popular child star, but when your time is up, it’s over — no one’s interested in you anymore. The truth is that even now, as an adult, I get comments like, ‘Enjoy your voice while you have it, by the time you’re 50 no one will be interested in hearing you sing.’”

“And just like every king needs subjects in order to feel his power, every performer needs an audience. The audience is your feedback, the metric of how you’re doing. Once you lose that, you can feel very lost. So you need to build up other interests, other sources of fulfillment, besides music. For me personally, after my voice changed, I threw myself into my learning and got a lot of satisfaction from it.”

Bentzy understands the impact of feedback. He knows how much power a good word can hold — even at his stage, with his best years ahead of him. “I get the motivation to push ahead when people tell me I’m going in the right direction and that there’s a purpose to what I’m doing. And then there are those who come up to me and say, ‘What are you doing here? Go to cheder.’ Once, a rebbi told me in front of a few talmidim, ‘You’re a child, why are you up on stage? Go learn.’ Later, he called me to apologize.”

For now, he’s focusing on the opportunities he has. And, he says, he’s learned a lot working with Motty. “I learned from him how to perform. How to pace myself. To connect with the audience. I looked at how he does it, how he draws the audience in. There’s a real skill to it.”

Motty has kind words for his young protégé, Bentzy, and also some practical advice: “Later, when your voice will change, they’ll try to preach to you. They’ll say you were just wasting your time with all that singing, and what did you gain from all those performances anyway?

“But you constantly need to remind yourself that Hashem gave you this voice, this talent, and you’re using it to serve Him. You’re singing songs that strengthen and inspire Yidden. True, the gift won’t last forever — every wunderkind loses his voice at some point and has to step off stage. But while you have it, try to value every note.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 956)

Oops! We could not locate your form.