Voice of History

Rabbi Berel Wein: An unquenchable love for the greatest saga of all — the survival of his people

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Mishpacha and family archives

For Rabbi Berel Wein, the historical narrative wasn’t just about the past, but about the present and future — about life itself, woven with the dramatic chronicle of unshakable Jewish faith. Yet his scholarly and rabbinic achievements rested on the foundation of his early life, growing up in Chicago among the previous generation’s gedolim — and on an unquenchable love for the greatest saga of all: the survival of his people

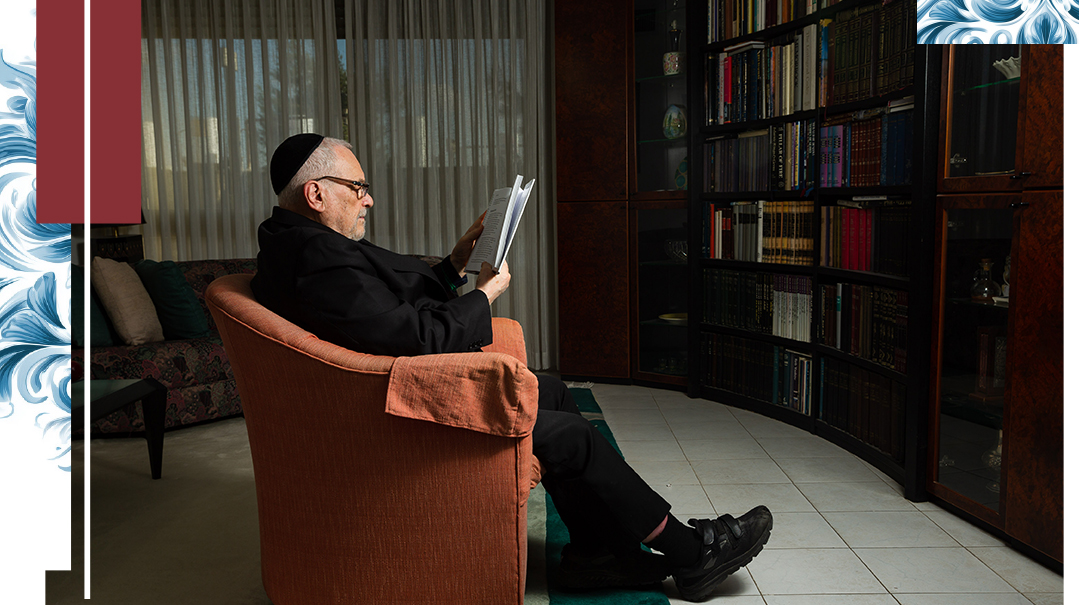

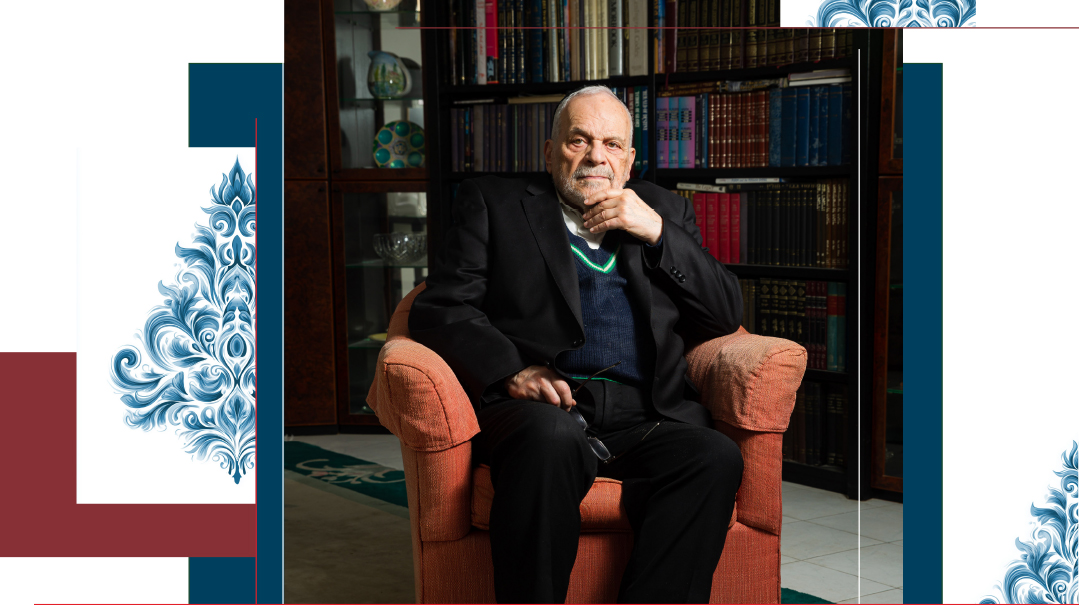

IF you walked into Rabbi Berel Wein’s Rechavia apartment in recent years, chances are you caught a glimpse of something rare: the sight of real thinking.

Not the mere brain activity that most of us engage in, but sustained, active thought. Head in hand, withdrawn from the surroundings, pondering something deep — that was my first impression of Rabbi Wein a few years ago, when I asked for some time to discuss a Jewish history project.

When I entered, I beheld a legend. The larger-than-life rabbi, rosh yeshivah and raconteur who’d placed volumes on all of our shelves, and Jewish history on the Orthodox world’s curriculum. There he sat, his sight failing but his penetrating vision ranging through the Jewish ages.

What I discovered in that first conversation was that for Rabbi Wein, history wasn’t about the past for its own sake. It was about the present and future — about life itself.

The way he made sense of the world was by unlocking the treasure-houses of what had already been. The conviction with which he lived — what drove him through a career of unusual variety and creativity — were those thousands of years of Jewish history.

History undergirded his sense of netzach Yisrael, the call of the Torah ranging across time, the awareness of Jewish destiny.

Shaped by Lithuania

Rabbi Wein, who passed away last Shabbos at 91, was born in 1934 into a house with a pedigree of greatness. His father, Rabbi Zev Wein, was a talmid of Rav Shimon Shkop in Grodno, and later of Rav Kook in Yerushalayim, who emigrated to Chicago and served in its rabbinate until the 1970s.

That lineage afforded Rabbi Wein junior a second-hand encounter with the masters of the prewar yeshivah world. Those impressions were reinforced by his rebbeim at Hebrew Theological College, later known as Skokie Yeshiva, founded by his maternal grandfather, Rabbi Chaim Tzvi Rubenstein.

Rabbi Rubenstein — whom Rabbi Wein described as his “hero” — was no ordinary personality either. He had been a chavrusa in Volozhin Yeshiva of the famous Meitscheter Illui, Rabbi Shlomo Polachek. It was he who set his grandson on the path to lifelong Torah scholarship.

He urged young Berel’s parents to remove their son from public school when he was 11 and place him in a class of 16-year-olds in the yeshivah. Until then, Mrs. Wein used to review her son’s school lessons with him every day, telling him what he should ignore.

The milieu that Rabbi Wein was raised in was that of Litvaks transplanted to American soil — an environment that was inhospitable to Orthodoxy until the great rise of the postwar yeshivah world. It manifested the complexity of Jews who came from a storied past, yet struggled with observance in the present.

“I can still summon up the atmosphere in my father’s shul on Rosh Hashanah,” Rabbi Wein said in an interview for this magazine. “During the Shemoneh Esreh, one could feel the intensity and that we were truly hanging between life and death, chayim u’maves. And many of those who davened in his shul felt compelled to work on Shabbos.”

The Midwest’s first yeshivah featured an all-star set of roshei yeshivah who were some of the finest minds of the Eastern European Torah world. One was Rav Chaim Kreiswirth, an illui who had been close to Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski in Vilna. Later a legendary chief rabbi in Antwerp, he became Rabbi Wein’s main rebbi. Other strong influences there were Rav Mordechai Rogow and renowned mechanech Rav Mendel Kaplan.

The affinity for old-world greatness nurtured under these teachers meant that Torah leaders as diverse as the Ponevezher Rav and the Satmar Rav saw Rabbi Wein as a figure of stature.

World of Books

Beis Medrash L’Torah, as Skokie Yeshiva was officially called, possessed a magnificent library, with 30,000 volumes, which were housed in a separate building. Since Berel’s classmates were much older and taller than him, instead of playing basketball with them during lunch break, he wandered into the library building.

There he nurtured his natural love of books. The librarian, Mrs. Mishkin, whose husband was head of the Vaad Hachinuch of the Associated Talmud Torahs of Chicago, would hand the young boy books to read, most of them on Jewish history. The first was a biography of the Rosh. Over a lifetime of voracious reading, Rabbi Wein would devour countless volumes.

Blessed with a sharp mind and phenomenal recall, his research on any given topic was informed by the library that he’d ingested.

In 1955, Rabbi Wein married Yocheved (Jackie) née Levin, whose father Rav Eliezer was a product of Kelm and a leading member of the Detroit rabbinate.

An education spanning Skokie Yeshiva, Yeshiva University, and then law school, meant that when he left the legal world, he entered his first rabbinic position at Beth Israel in Miami Beach in 1964 with an unusually diverse skillset. He was a leader, educator, and writer all rolled into one.

Given his background and clear aptitude for rabbinics, why did he practice law at all? In an interview with Mishpacha, he explained that the realities of the time dictated his career choices.

“When I graduated college at 18, my father took me aside and spelled out the facts of life. We had little money. The number of shuls in Chicago was in rapid decline, and the chances of securing a pulpit were slim. A relative told my father that he would bring me into his small firm if I passed the bar.

I was accepted at the University of Chicago Law School, one of the country’s best, but I wanted to continue in the semichah shiur at HTC, and so I went to DePaul Law School at night.”

In the tussle between parnassah and purpose, the latter eventually won out — helped along by a dose of disenchantment with the law as a profession.

“In the practice of law, you tend to see people at their worst, and since most of my clients were Orthodox Jews, I found that extremely disheartening,” Rabbi Wein said.

“Rav Chaim Kreiswirth, who had been my rosh yeshivah, often told me on his frequent visits to Chicago that there were enough Jewish lawyers. And indeed, I eventually started a tool-and-die business to enable me to get out of the practice of law.

“One day, as I was closing the business, I found my old friend from yeshivah Rabbi Aryeh Rottman waiting for me.

“I’m leaving my shul in Miami Beach, and Rabbi Kreiswirth says you should be my successor,” he told me.

“I replied that I wasn’t interested, but Rabbi Rottman was not someone who took no for an answer, especially when on a mission from his rosh yeshivah. Eventually, he prevailed on me to go for a trial, and I was offered the job after a very narrow congregational vote. Fortunately, by the time I left nine years later, I think I would have won a unanimous or near unanimous vote.”

Practice and Preaching

Sometimes, lost in the hindsight of his writing career was the very practical and multifaceted nature of decades of previous work. From 1964 to 1972, Rabbi Wein served as Executive Vice President of OU Kashrus, a period in which the organization attained its global prominence thanks to Rabbi Wein’s work.

The OU position came about through a connection formed in Miami Beach. Rabbi Alexander Rosenberg, the director of the OU Kashrus Division, appointed Rabbi Wein as a mashgiach at various nearby food producers. Over the course of two decades, Rabbi Rosenberg built the Kashrus Division from 40 mashgichim, certifying 184 products of 37 companies, into an organization with 750 mashgichim, 2,500 products, and 475 companies. The two rabbis struck up a close relationship, which paved the way for Rabbi Wein to enter the OU’s top ranks.

The next stop in 1972 was Suffern, New York, where Rabbi Wein became rav of Bais Torah Congregation in Rockland County.

Over the next 25 years, he had a transformative effect on the community. He founded Yeshiva Shaarei Torah, developed chessed institutions, and attracted young families to settle and build Jewish life.

During those years, congregants were exposed to the signature blend of Torah, history, and dry humor that later became famous worldwide.

That groundbreaking combination of erudition and style burst into cars and living rooms across the Jewish world in the 1980s. Rabbi Wein would retell the encounter in Yerushalayim in which he concluded that — as good as his chiddushim as a rosh yeshivah in Monsey were — others could do that job.

His own calling was to tell the story of Am Yisrael. That fateful encounter led to the Destiny series of tapes, books, and movies on Jewish history.

Within a few years, his coffee-table edition trilogy Herald of Destiny, Triumph of Survival, and Echoes of Glory adorned homes and shuls across the English-speaking world. The publishing process turned Rabbi Wein and Artscroll general editor Rabbi Nosson Scherman — who edited many of his books — into good friends.

“The relationship was far deeper than merely professional,” says Rabbi Scherman. “Although Reb Berel was a genius and an excellent writer, he welcomed suggestions and editing. He valued accuracy over ego. It was not only an education, but a pleasure to work with him.”

The landmark 4-volume history series presented the story of the Jewish people across the centuries, leavened by his acute observations, constructive cynicism, and gentle humor.

“He was a master at combining Jewish and general history and showing how our people were affected by, and coped with, the powers and events that surrounded and often subjugated them.”

Along the way were flashes of his trademark wit, Rabbi Scherman remembers. “An interviewer asked him how he arrived at the title, Herald of History. He replied, “Harold is a Jewish name, isn’t it?”

Past Forward

His feat was to transform history — to many, a dusty discipline — into the dramatic narrative of Jewish faith that it should be. The pre-eminent popular Jewish historian, he knew how to retain the grand sweep of a saga, while retaining the accuracy demanded of history as a discipline.

Always focused on the Jewish future, Rabbi Wein believed firmly that the post-Holocaust revival that had two great centers — Israel and America — would tilt ever more firmly in the favor of the Holy Land.

“Every exile ends, and that end is not usually a happy one,” he said. “I can well imagine an America in which the government tells religious Jews what they can and cannot teach in their schools, and in which religious liberty is gradually whittled away. By contrast, in Israel, I have witnessed over the last 30 years, that the society as a whole has become more and more Jewish. That can easily be missed if we focus too much on the day-to-day religious battles and ignore the long-term trends.

“But the one absolute principle of Jewish history is that Jewish communities only flourish when there is a strong core of Torah learning and mitzvah observance.”

Given those beliefs in the Providential rise of Eretz Yisrael as the focus of Jewish history — now rushing toward its conclusion — it’s no surprise that Rabbi Wein chose to put his money where his abundant words were.

That’s where he and his wife directed themselves in 1997, where Rabbi Wein — pulpit rabbi, historian, and visionary — attained the prestigious podium of the Beit Knesset Hanasi in Rechavia.

From that leafy Yerushalmi neighborhood, his prolific output continued to flow, the Torah of destiny emanating from Tzion continuing beyond his own petirah in the form of yet to be published writings.

So prolific was his output — both print and oral — that a standard tribute is largely unnecessary, since Rabbi Wein was himself his own biographer. What follows are tributes from family, students, and colleagues. They paint a picture of a unique rabbi — one who followed his inner calling to amplify the Bas Kol, the booming Heavenly Voice that resonates out of Jewish history.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1075)

Oops! We could not locate your form.