Virtual Echo Chamber

I’ve been writing about American politics more than is my wont the past couple of weeks. That is not the result of a sudden upsurge in interest on my part, but out of a desire to clear the docket, and, more important, my mind in advance of Elul.

Political debate in America, such as it is, increasingly sucks one into modes of thought that are profoundly unserious and ways of speaking and writing that lower one. Resisting the slide into partisanship on behalf of one team or another requires ever greater energy.

In particular, I’d like to broaden my scope this week to consider some of the larger societal trends behind our increasingly divisive political discourse. Chief among those is rapid technological change. Economic historian Niall Ferguson argues that one would have to go back to the invention of movable type in the mid-15th century to find another example of such massive disruption of the public sphere as that created by the personal computer and the Internet.

Both the printing press and the Internet sharply reduced the cost of producing material for public consumption and therefore dramatically increased the volume of material available. The graphs of lower production costs and greatly expanded material are almost identical. The only difference: The time span over which those changes have taken place is nearly ten times faster today.

The period immediately following the invention of the printing press, Ferguson notes, was one of ruinous religious wars in Europe. The distance between verbal violence — “You’re a heretic;” “No, you’re a heretic” — and physical violence often proved to be a short one indeed. One hundred and thirty years of religious wars only came to an end with the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648.

Another feature of the earlier period was the proliferation of “fake news” — again, with often disastrous consequences. One of the best-selling works of the 16th century claimed that witches were widespread and needed to be burned to death, a prescription that was frequently acted upon.

Rabbi Daniel Feldman’s new work, False Facts and True Rumors: Lashon HaRa in Contemporary Culture, combines learned halachic discussion with the latest sociological findings. He marshals a good deal of the latter to describe how the Internet has created virtual communities of like-minded individuals, who rarely confront a contrary opinion or any reality testing of their ideas.

While the information-spreading power of the Internet theoretically allows for better error correction than traditional media, as Judge Richard Posner argues, that is only true to the extent that people pay any attention to opposing views or dissonant facts. And the latter becomes less likely due to the tendency of online users to interact primarily with those with whom they identify.

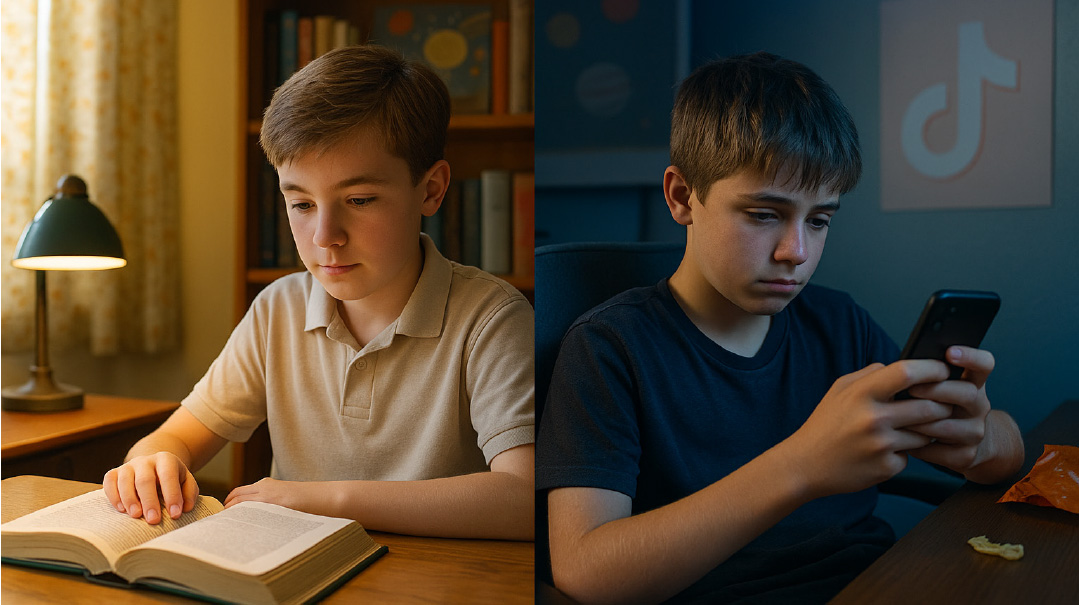

William Davidow argues in Overconnected: The Promise and Threat of the Internet, that the Internet fosters “thought contagion” through the positive feedback processes of like-minded individuals. The segregation effect of people into like-minded groups happens much faster and with more extreme consequences on the Internet than was ever possible before.

One consequence is loss of empathy for those not identified with one’s group. Susan Cain, in Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, cites a 2010 University of Michigan study that college students are 40 percent less empathetic than college students were 30 years ago.

EVER MORE DIVISIVE POLITICS is the result of these virtual echo chambers. And one of the casualties of a debased and angry political discourse is the ability to address the most important issues facing a polity.

Take one such issue: educational policy. Automation, information technology, and globalization are factors resulting in rapidly decreasing job security across all economic levels and a rapid decrease in the demand for low-skilled labor.

Education for a constantly and rapidly changing job market should be at the very top of issues being discussed by those who would lead us. Yet one could listen in vain during the Democratic debates so far for any mention of educational policy. Forgiveness of college loans and free college for all do not count. At a time when higher education appears to be producing more and more non-resilient snowflakes, ill-prepared, in the main, for gainful employment, a compelling argument could be made for less college, rather than more, and a focus on technical education.

The same lack of serious discussion applies to responses to China’s efforts to attain global military and economic superiority employing wide-scale industrial espionage, currency manipulation, dumping, and copyright and patent theft. One need not be in awe of President Trump’s negotiating tactics to think that politicians should be discussing counterstrategies.

The national debt doubled under President Obama, and continues to skyrocket at an unsustainable rate under President Trump. Yet neither major party is even paying lip service to the threat. With bipartisanship a relic from the past, there is no hope of even putting the issue on the agenda. Much easier to continue making unaffordable promises of free stuff, and dare the other party to say no.

A politics centered on virtue-signaling of one form or another to respective party bases and name-calling against the other side is demonstrably incapable of dealing with a rapidly changing world. And for now, no other form of political discourse is on the horizon.

No to Reparations

The call for reparations to descendants of African slaves by the leading Democratic candidates is typical of what is wrong with American politics. Each of those candidates knows that reparations will never be enacted. Three-quarters of Americans oppose them, including about one-third of black Americans.

But as means of stirring the base, increasing the sense of black victimhood, and signaling one’s “wokeness,” reparations are ideal.

But first a question: What about German reparations to survivors of the camps and those who had their property stolen? While there were many in Israel, including Menachem Begin, who were bitterly opposed to the acceptance of German “blood money,” those reparations played a major role in the development of the early Israeli economy.

Two answers. Those reparations were, by and large, paid to the actual victims of the Nazis for damages inflicted upon them and property stolen — as was also the case with reparations paid to Japanese who were interned in World War II. And they were paid by a nation whose government had made the extermination of the Jews its highest priority. By contrast, we are today speaking about descendants of slaves generations removed. And the ancestors of many of the taxpayers who would be asked to foot the bill — including almost all American Jews — arrived in America long after the abolition of slavery by the 13th Amendment.

But the worse thing about reparations is that it would signal the end of the ideal of color-blindness and of the sovereign individual, and its replacement by group identity. And in so doing, it would set racial groups against one another as perpetual adversaries, like union and management, without even the shared interest in the long-term viability of the company.

So long as all differentials, such as median income, are chalked up to “the legacy of slavery,” there can be no closure, only group litigation in perpetuity. The scab of slavery would be constantly bleeding.

Coleman Hughes, a black philosophy major at Columbia, testified against reparations in congressional hearings. He told a subcommittee of the House Judiciary Committee that while the failure to pay reparations to the freed slaves themselves was an injustice, the focus on slavery today only distracts from what black communities require — safer neighborhoods, better schools, an expanding economy. The payment of reparations today would only further divide the country, and prevent the formation of the types of coalitions required to advance those goals.

Hughes attested that he had no desire to be turned into a victim without his consent or to put a price on the suffering of his ancestors. He concluded:

“The question is not what America owes me by virtue of my ancestry; the question is what all Americans owe each other by virtue of being citizens of the same nation.... The obligation of citizenship is not transactional. It’s not contingent on ancestry, it never expires and it can’t be paid off.”

Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 776. Yonoson Rosenblum may be contacted directly at rosenblum@mishpacha.com

Oops! We could not locate your form.