Vaad Hatzalah Mitzvah Tank

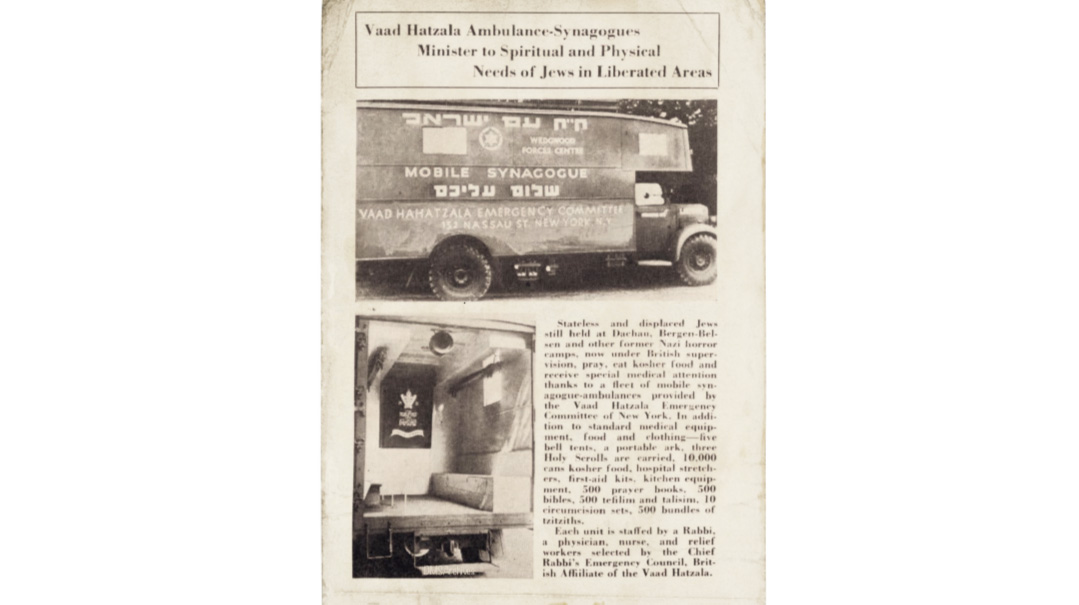

| July 5, 2022One of the Vaad Hatzalah’s innovations was the “ambulance synagogue”

Title: Vaad Hatzalah Mitzvah Tank

Location: Germany

Document: Vaad Hatzalah Circular

Time: 1945

When General Alfred Jodl signed the German Instrument of Surrender in Reims, France, on May 7, 1945, and Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel did so the next day in Berlin, the guns finally fell silent on the European continent after nearly six years of devastating bloodshed. While the world celebrated V-E Day on May 8 and 9 and servicemen began returning home, the few Jewish survivors of the Holocaust only began to internalize the full scope of the tragedy they had experienced.

A period of physical rehabilitation was soon followed by searches for relatives, attempts to return home, and the dawning realization for many that they were alone in the world with nowhere to return to. The Allied militaries established Displaced Persons (DP) camps, which were administered by UNRRA. As attested by the Harrison Report in the summer of 1945, the survivors were kept in horrid conditions, and it was up to Jewish American philanthropic organizations — primarily the Joint — to provide for the physical needs of the survivors.

The Vaad Hatzalah was an American organization established by the Agudas Harabbonim in November 1939 to assist refugee rabbis and yeshivah students. In late 1943, the Vaad expanded its activities to include Holocaust rescue. With the war over, the Vaad focused its activities on physical and spiritual rehabilitation for the survivors in the DP camps. This would later come to include provision of religious articles, kosher food, Jewish educational facilities, printing of seforim, and more.

In its initial stage, however, it was imperative to expedite relief and reach those who needed it most. One of the Vaad Hatzalah’s innovations was the “ambulance synagogue” — a standard ambulance stocked with standard medical equipment and staffed by physicians and nurses, augmented with supplies of sifrei Torah, siddurim, talleisim, tefillin, tzitzis, and kosher food, with a rabbi attached to the staff for good measure. These mobile synagogues were able to reach a wide number of survivors, providing critical relief during the early months after liberation.

While their physical needs were being tended to, the survivors had the opportunity to reignite their religious identities, which had lain dormant during the terrible years of war, ghettos, camps, and hiding. The Vaad Hatzalah extended a lifeline of hope to many survivors, many of whom had despaired of ever returning to their heritage following the loss of their families and communities. These mobile synagogues made their rounds of the DP camps, and for many survivors served as the impetus for a return to mitzvah observance.

A Defining Dinner

On December 17, 1945, Vaad Hatzalah hosted a dinner for 1,800 guests to raise funds and honor Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau. Irving Bunim made an appeal, reminding his audience that there remained much work to be done in Europe. Using a compelling anecdote, he asked the audience’s permission to read a newspaper advertisement for winter coats for dogs, priced at the then-princely sum of $260.

“Can you imagine,” he said in a voice choked with emotion, “what our downtrodden brothers in the camps would think of such absurd luxury while they are struggling to pull together the broken pieces of their shattered lives?”

The audience’s shock and sorrow rose with Bunim’s. The night’s appeal netted over a quarter of a million dollars.

Rehabilitative Chocolates

In the fall of 1946, on the urging of Rav Aharon Kotler, Vaad activist and famed philanthropist Stephen Klein embarked upon a three month fact-finding mission at his own expense. Before he left the States, he shipped clothing, shoes, underwear, candies, and seforim through the Vaad Hatzalah Committee in Paris. Klein brought chocolates from his own factory, a luxury in postwar Europe, and used them to thank officials who provided assistance.

After six weeks in Europe, Klein wrote to his friend Benjamin Pechman that he was working an average of 18 to 20 hours a day. To save time, he worked during the day and traveled by train or car at night. He visited embassies and consulates to determine how to facilitate the immigration process.

“You cannot imagine the sort of conditions that these unfortunate people are in, especially those that have arrived in Germany during the last few months. They are mainly Orthodox Jews. I cannot understand how I can remain sane after seeing all the terrible tragedy that is happening to our people. How big the Zores Israel is suffering cannot possibly be described on paper.”

In honor of Elliot Mandelbaum for all that he’s accomplished on behalf of the Vaad Hatzalah for Ukrainian Jewry.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 918)

Oops! We could not locate your form.