Unpacking Agudah’s Attic

Rabbi Moshe Kolodny guards the forgotten treasures of a lost world

Photos: Naftoli Goldgrab

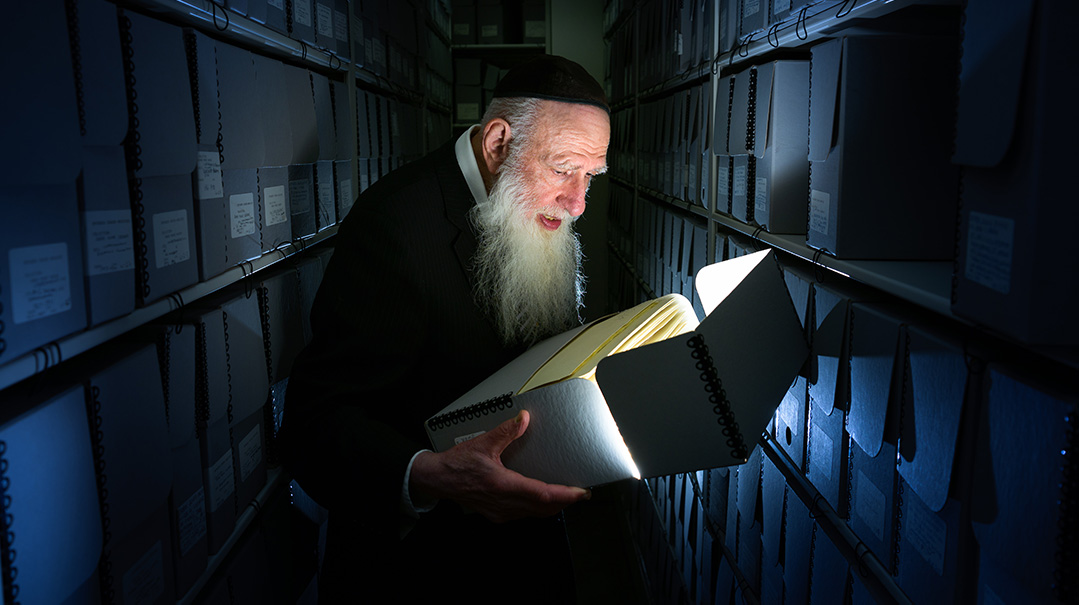

Fourteen stories above Lower Manhattan, in an unexceptional room at the far end of a hallway in Agudath Israel’s headquarters, is Rabbi Moshe Kolodny’s fiefdom. Surrounded by 100,000 books, documents, photos, and audio recordings, the heroes and villains, the bravery, the malevolence, and quirkiness of the human race, are at his fingertips.

“He knew all these things before Google,” Rabbi Labish Becker, Agudah’s executive director, tells me.

But Rabbi Kolodny could have one advantage over Google — his memory might be better.

When Mishpacha writer Dovi Safier was conducting research for his article last year on Rav Leib Malin, he did an exhaustive search for an elusive recording of the Beis Hatalmud rosh yeshivah’s levayah. He finally called Rabbi Kolodny.

“No, I don’t have the recording,” Rabbi Kolodny said. “But I was there.”

He then proceeded to recite Rav Yisroel Gustman’s hesped of Rav Malin, word for word, by heart.

“To me,” says Safier, who loves to spend time among the archive’s treasures, basking in Rabbi Kolodny’s knowledge, “it was one of the most powerful parts of the article. It was the night before I closed the article, and it was the last thing I put in. He really made it all come together.”

“Rabbi Kolodny’s knowledge of American Orthodoxy is only surpassed by his kindness,” says Dr. Zev Eleff, president of Gratz College and a noted frum researcher and historian. “On so many occasions, Rabbi Kolodny welcomed me into the archives, talked about the old days at Chaim Berlin, and shared the treasures that he and the Agudah have collected over the decades.”

Classes visit. Researchers comb its shelves. A bookworm could be busy for a month there. The smell of paper is intoxicating.

“You have to be interested in this,” Rabbi Kolodny muses. “If you’re not interested in it, then it’s boring. But if you are interested...” His voice trails off in nostalgic delight. “It’s a kosher yetzer hara.”

Rabbi Kolodny, who lives in Flatbush, didn’t offer his age, and I didn’t ask. But he had Rav Yitzchok Hutner as rosh yeshivah and Rav Avigdor Miller as mashgiach, which would put him in his mid-80s. His thin face is framed by a snow-white beard, and he speaks with a Brooklyn twang.

The walls of the room, which I estimated is about 40 feet by 40 feet square, display large, nearly life-sized photos of Jewish life of the past — girls in studious concentration at Bais Rochel of Williamsburg in the 1960s, a line-up at Yeshiva of Eastern Parkway in 1965, celebrating Succos in the then-heavily Jewish neighborhood of Brownsville in 1949, the pushcart market on Osbourne Street (today called Mother Gaston Boulevard) in Brownsville, a 1935 rally on Division Avenue in Williamsburg.

“Who knows what they were protesting?” Rabbi Kolodny says with a shrug.

Pictures, I notice, are ubiquitous at Agudah’s offices. The long hallway leading to its conference room is festooned with historical imagery, and every room has photos of gedolim or bygone events. If the Capitol in Albany has its Hall of Governors, Agudah has its Hall of Gedolim.

One large picture depicts, in surprisingly high-resolution, the 1923 Knessiah Gedolah in Vienna, which came back into the headlines several years ago when footage was discovered of the Chofetz Chaim, the Chorktover, and other gedolim at the event. Faces and other details were readily recognizable, as was a sign near the entrance declaring “Rauchen Verboten” — the original “no smoking” sign.

I notice one remarkable detail I hadn’t seen before — organizers set up a press section in the front of the hall, where writers sat, pens in hand.

“Yossel Friedenson told me,” Rabbi Kolodny says, observing my reaction, “that the Agudah events had the yekkehs there, so they were more organized and had a press section. But the Zionists were all Russian, so they didn’t think of this. That’s why the Agudah conventions had more press than the Zionist conventions.”

History or Junk?

The documents, books, Yizkor books, microfilms, photos, audio recordings, journals, and reports in the archive had to meet criteria that are detailed, yet broad.

Rabbi Kolodny tells me that for an item to be accepted to the archive, it must be “something whose history reflects on the contributions of Orthodox Jewry.”

But that grandiose mission statement is usually accompanied by a hidden asterisk — anything that comes to the Agudah office and has no other place will invariably end up in the archive. This explains the box of old Jewish Observers lying in the corner, or the pile of recent Torah journals, such as Yeshurun or Kovetz Beis Aharon V’Yisrael, atop a side table.

“Yeah, sometimes we just have things because people brought them in here,” the archivist concedes. “But generally things are here because they fit the criteria.”

For nearly 45 years, Rabbi Kolodny has been collecting, cataloguing, preserving, and presenting his work. He has an eye for what is historically important and what is junk in the basement that he can’t throw out.

“Moshe Prager used to say,” he said, referring to the famed Polish-Jewish author and historian, “95 percent of an archive is junk, and only five percent is needed. But you never know where the five percent is.”

I ask him if he can identify that necessary five percent in the Agudah archive.

“With the Agudah, things are different,” he asserts. “Take the Rosenheim file” — referring to papers of Agudah’s first world chairman, Rav Yaakov Rosenheim. “It’s important for people who want to know what happened. We have researchers coming in here all the time.”

“You have to be interested in this. If you’re not interested in it, then it’s boring. But if you are interested,it’s a kosher yetzer hara”

A Day in the Life

What does an archivist do?

“First of all,” Rabb Kolodny said, “I try to get material. Second of all, there are ways of preserving documents — it never was a whole college degree, but there are basic rules.”

Storing materials in acid-free boxes is one rule, for example. The archive is climate-controlled, since some of the documents are sensitive to the slightest change in temperature.

“Anything that needs more preservation than that,” Rabbi Kolodny says, “I send away.”

One such item was the original handwritten notebook of Rav Elchonon Wasserman, which eventually was published as Ikvesa d’Meshicha.

“He had a really nice handwriting,” Rabbi Kolodny adds, parenthetically.

The precious notebook was sent to the same company that preserves the original copies of the Declaration of Independence. The company’s personnel came with a car, took it to their laboratory to be treated, and sent it back. The notebook is not currently held in the archive.

Rabbi Kolodny also hosts regular tours for schools, usually of classes full of girls, who come by every once in a while to peruse the archive.

“They mostly want to know if I have information about their grandparents,” he says. “But these visits have tapered off recently. It’s a different dor today.”

Rabbi Kolodny considers the Rosenheim file one of the most valuable in his archive. Rav Rosenheim, known as “Moreinu,” led Agudah from its inception through the turbulent war years, and had his hand in every pot. His records have shed new light on that era, and are among the most requested by researchers visiting the archive.

Doctorate students make up the bulk of visitors. The summertime, when students generally begin their research for their PhD theses, is his busiest season.

For example, a PhD student from Chicago once stopped by. He was researching the contributions of Jewish scientists and wanted to know the attitude Rav Moshe Feinstein had toward science. Rabbi Kolodny was able to give him an original teshuvah from Rav Moshe on the topic.

More recently, representatives from the Japanese government came to the archive. They are planning to commemorate Chiune Sugihara, Japan’s consul general to Lithuania who is credited with saving thousands of Jews, including the Mir Yeshivah, and they were researching his life.

Such a quantity of dry paper presents a serious risk for fire. Indeed, the room has had its fair share of conflagrations, most of which afflicted the photo archive. A 1988 New York Times article reports on one such disaster, recounting that 70 percent of the archive, including “journals, newspapers, letters, and diaries, some smuggled out of death camps in Europe, are in ashes in a charred room. Other documents are singed and brittle.” Today, images are mainly stored on microfilms.

Some of the most interesting questions he has received over the years involve the complicated relationship German rabbanim had in the early years with Moses Mendelsohn, the father of modern Haskalah. A learned man, Mendelsohn published a commentary on the Torah that deeply impressed many rabbanim. It was only later on, when his movement shifted away from traditional Jewish practice, that the schism became apparent.

Archivist Rabbi Moshe Kolodny was around for research long before Google – and his memory is better

Building from Scratch

The germination of the archive came in the 1970s, when the records of the organization’s first president, Elimelech “Mike” Tress, were transferred to the Agudath Israel office. They lay in storage at the eighth floor office at 5 Beekman Street for years, untouched.

In 1981, Agudah received a one-time $34,172 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities “to support cataloging of collections at the Agudath Israel Archives concerning Orthodox Jewish America in the 20th century.” Agudah accepted the grant and began looking for someone to begin the process of cataloguing its history.

Rabbi Kolodny was davening at the time at the Agudas Yisrael minyan on Kings Highway, near where he lived.

“I was in between jobs, they were looking for somebody, I decided that I liked this stuff, so I took it,” he recalls. “It was supposed to be for one year, but it stretched to over 40 years. And now here we are.”

For both Rabbi Kolodny and the Agudah, it was a Goldilocks moment that cemented the arrangement. Rabbi Kolodny, a seforim connoisseur, had just ended an 18-year teaching career.

“From the days I was in Chaim Berlin in the ’50s, I liked seforim, and I was the librarian there,” he says. “I liked this kind of stuff, but I didn’t think it would be a career. But life happens. It earned me a parnassah, and it married off my kids.”

After his marriage, he had given a shiur for ninth grade at his alma mater, which was then located in Far Rockaway. The yeshivah had received an offer from the city to purchase a former public school building for one dollar. The thinking at Chaim Berlin was that they would bus the students in.

But parents objected to the arrangement, which had children commuting for 45 minutes twice a day, and enrollment plummeted. Chaim Berlin eventually relocated to Flatbush and is today a premier yeshivah in the area. In the meantime, though, left without a job, Rabbi Kolodny returned to kollel. It was at that point that he was approached about becoming Agudah’s archivist.

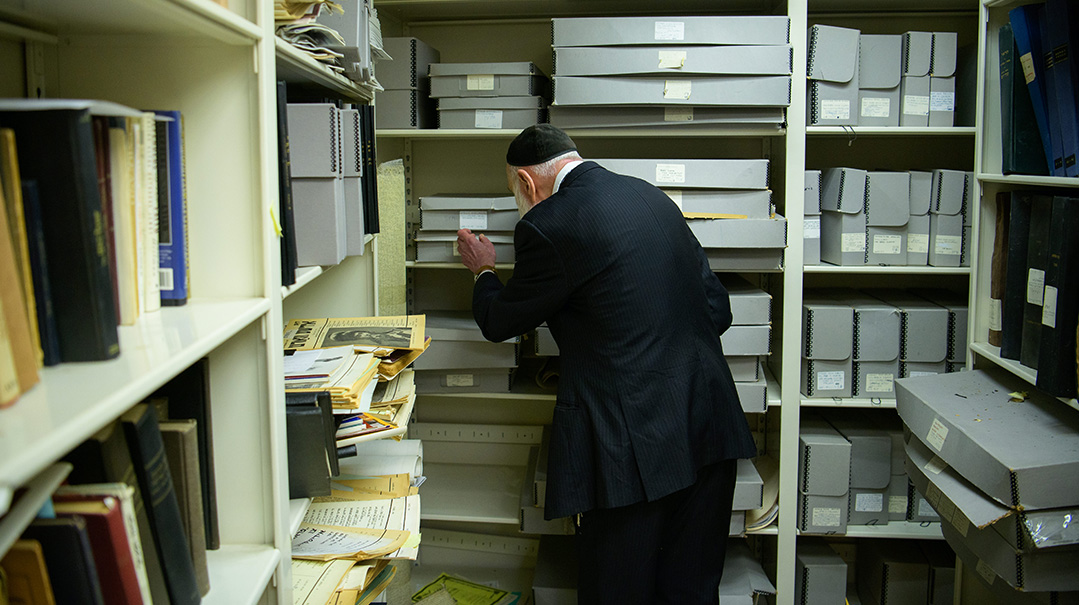

When Rabbi Kolodny came in for his first day of work, he literally had to start from scratch.

“It was just a bunch of files piled up in two-foot-tall boxes,” he says. “There were the Tress records, and then a whole file of records from Rabbi Moshe Sherer came in. From there we were able to branch out and make an archive of Orthodox Jewry in America. And along the way we picked up some very interesting things.”

Keeping it Simple in Prague

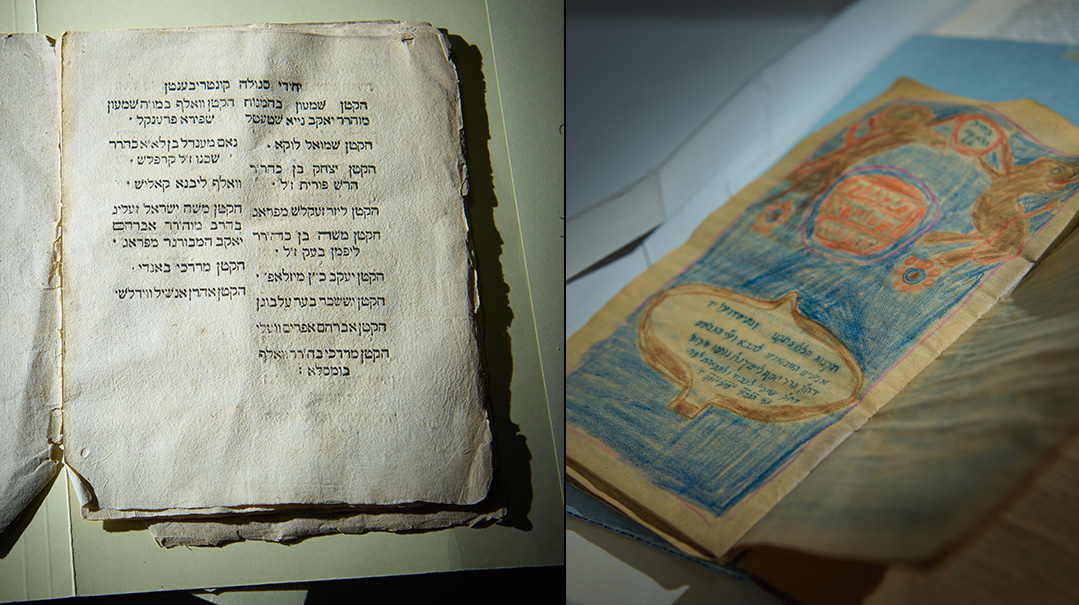

The Noda B’Yehudah’s takanos, 1767

Coronation announcement for Emperor Francis II, 1804

The crown jewel of the collection is also its oldest file — a printed list of takanos to scale down ostentatious simchahs in Prague. Dated in 1767, for parshas Ki Seitzei — apparently in advance of Elul — the first signature was that of Rav Yechezkel Landau ztz”l, author of Noda B’Yehudah. “Mit den unwissenheit excuseren nisht,” the title page warns in bold, archaic, calligraphic script — 250-year-old German for “ignorance of the law is no excuse.”

“This is the original document published by the Noda B’Yehudah,” Rabbi Kolodny declares. “And they wrote on the cover, ‘We printed it, and there is no excuse for not following it.’ ”

The list of takanos is extensive, eight pages touching on such familiar topics as the number of invitees permitted for a bar mitzvah — “from the largest to the smallest” — how many musical instruments may be played at chasunahs, and how much money may be spent on these events. The calligraphers of the day certainly did not lack for parnassah.

The proclamation was addressed to the “Prager Judenschaft” and issued by “Uber Rabbiner Ezekiel Landau.” Prague at the time was the crown of the Jewish world, one of the three most populous kehillos in Europe, along with Frankfurt and the combined kehillah of Altona-Hamburg-Wandsbek.

Another document from Prague is dated December 8, 1804, and was published in honor of the day of thanksgiving called by the rabbanim to mark the coronation of Emperor Francis II of Austria. The “herzengefuhl und gebet,” or thoughts and prayers, of the Jews of Prague were firmly with the Kaiser Franz der Zweiten, the “Roman emperor,” on his big day.

Also on Jewish minds that day was his empress, Maria Theresa, later notorious for her expulsion of Jews from parts of her realm. But on that day, it was all wine and roses. The entire community, the proclamation proclaimed, would gather before davening on Shabbos to recite six perakim of Tehillim, and later say a special tefillah composed for the occasion.

“Rejoice, O nation of Bohemia!” proclaimed the pamphlet. “Long live our master, Kaiser Franz. Long live the queen, the Kaiserin Maria Theresa. May they and their children rule over Austria until the end of days.”

“Ach, she was such an anti-Semite,” Rabbi Kolodny says in disgust. “But they did what they had to in those days.”

The pair of rare documents was gifted to Agudah by the late Rabbi Dr. Elie Munk of Berlin, the chief rabbi of Ansbach, Germany, who in 1936 fled to France and became rav of Paris. He bequeathed parts of his library to Rabbi Kolodny before his passing in 1981.

A Meeting With the Fuehrer?

Dankschift far dem Reichskanzler, from German rabbanim, October 1933

One of the most astounding items in the archive was a 14-page missive penned by a consortium of rabbanim in Germany upon Adolf Hitler’s appointment as chancellor on January 30, 1933. Hitler’s victory had caused great consternation in the West, and the secular Jewish establishment organized rallies to push for official boycotts of German goods.

Hitler, who still faced a parliamentary election and had won without a majority, had been furious at the calls for a boycott. The rabbanim — Rabbis Elie Munk and M. Auerbach of Berlin, Rabbi Moshe Schlesinger of Halberstadt, and Rabbis Shlomo Ehrman, Yaakov Rosenheim, and Joseph Breuer of Frankfurt — were aware of Hitler’s hatred for Jews and were concerned he would retaliate by making Jewish life even more tenuous in Germany.

The letter, dated October of 1933, would have been written a little over a half year after Hitler took office. It was titled “Dankschift far dem Herr Reichskanzler — Thank you to the Chancellor.” It is hard to imagine Hitler getting a letter from a group of rabbis. Moreover, it begins with the eerie statement that the rabbis feel “required to present to you an honest opinion on the German Jewish question.” The question, as history tragically bore out, had a final solution.

The letter is aimed at addressing Hitler’s frustration with the boycotts, while informing him of the hardships his draconian series of laws were causing the Jewish community. I read the letter through a translation app, and later found a small part of it translated on Yad Vashem’s website. The original, though, is at Rabbi Kolodny’s archive.

The letter declares the eternal allegiance of German Jews to the government, especially in battle against “godless Marxists.” It pronounces the boycotts against Germany a “catastrophic error and a grave injustice,” but noted that they have no control over what Jews in other countries do.

“The position of German Jewry today, as it has been shaped by the German people, is wholly intolerable,” the rabbis write, “both as regards their legal position and their economic existence, and also as regards their public standing and their freedom of religious action.” It enumerates the Nazis’ early persecutions of German Jews, excluding them from public service, culture, science, medicine, law, and academics. An anti-Jewish boycott had decimated the ability of Jews to earn a living, and thousands of Jews had been laid off from their jobs.

“The Jews are excluded everywhere from the occupational structure of the new Reich,” it laments. “This means, then, that the German Jew has been sentenced to a slow but certain death by starvation.”

The letter also mentions the ban on shechitah and restrictions on religious life.

“Thus the position of German Jewry must be perceived as altogether desperate by the most objective of observers the world over, and one must understand that the German National government might all too easily be suspected of aiming deliberately at the destruction of German Jewry,” the letter — incredibly — states, adding in italics that “this false concept must be disproved with concrete arguments if an information campaign is to have any effect.

“Orthodox Jewry is unwilling to abandon the conviction that it is not the aim of the German government to destroy the German Jews. Even if some individuals harbor such an intention, we do not believe that it has the approval of the Fuehrer and the government of Germany. But if we should be mistaken, if you, Mr. Reich Chancellor, and the national government which you head… have indeed set themselves the ultimate aim of the elimination of German Jewry from the German people, then we do not wish to cling to illusions any longer, and would prefer to know the bitter truth.”

The letter concludes with a request for a personal meeting with Hitler.

There is no record of that request being fulfilled. I ask if Hitler responded to the letter.

“It should be somewhere, but we don’t have it,” Rabbi Kolodny says. “Maybe he didn’t respond. They probably thought it would pass over, like all the other gezeiros that happened.”

Like those of Maria Theresa.

Frau Schenirer’s Nachas Call

Bais Yaakov Almanac, ca. 1917

Dispersed throughout the smallish room are hundreds of books and journals documenting every incident, controversy, community, culture, and clash related to Jewry in America and around the world the past two centuries.

I scan the shelves, discovering books about subjects I’ve never heard of. The Unfinished Story of Yiddish, Jewish Farmers of the Catskills, The Jews of Oregon, History of the Jewish Experience in Arkansas from 1820s to 1890s. There are some more familiar titles such as The Jews of Brooklyn. Two books lie side by side, perhaps intentionally — Faith Amid the Flames by Yossel Friedenson, and Faith After the Flames by Rabbi Yaakov Avigdor. The Ksavim of Yaakov Rosenheim rubs jackets with Rabbi Paysach Krohn’s Traveling With the Maggid.

Boxes of old Jewish Observers lie in a corner, stuffed there by an office mate looking for somewhere to stash them (where else should they go but the archive?), next to a collection of Dos Yiddish Vort, Reb Yossel Friedenson’s life project. Tens of thousands of documents, housed in floor-to-ceiling adjoined cabinets that take up most of the room, are accessed by a pulley system separating them.

Many of the files have names that clearly identify the contents. Then there are binders merely marked “Tress collection,” “Sherer collection,” “Silbermintz collection.”

“Josh Silbermintz saved everything under the sun,” Rabbi Kolodny tells me as he slowly wheels open the closet doors, referring to the legendary founder of Pirchei.

There is an entire shelf documenting Torah Umesorah’s fights to establish day schools in cities and towns that did not want them. A bulging binder marked “Isaac, Recha Sternbuch collection” contains telegrams in all-caps text and letters, ranging from the ambitious proposal to the Nazis to trade trucks for Jews, to requests for siddurim and food.

“Anyone who wants to know the history of the Bais Yaakov movement has it right here,” says Rabbi Kolodny, tossing several binders onto the table. “We’ve got the minutes of Sarah Schenirer’s meetings.”

He says this material was given to the archives by Rebbetzin Judith Grunfeld, who started the Bais Yaakov movement along with Sarah Schenirer.

One paper is titled the “Bais Yaakov Almanac” and it contains letters by “Frau Schenirer.”

“Every day,” one entry from 1917 declares, “new children arrive to be registered. … When I sewed clothes for Jewish girls, I would ask their mothers whether they would agree to give me their daughters to sew up their neshamos. The mothers agreed, I rented a room and gave my first lecture to 25 Yiddishe girls.”

Frau Schenirer writes of an amusing incident that happened after she taught her students to make a brachah every time they eat “from G-tt’s gift.” If not, they would be stealing, she remonstrated. The next day, she writes, a mother came to her saying that her six-year-old daughter noticed how her five-year-old brother was drinking water without reciting a brachah. “She screamed at him, ‘Ganav! When you drink G-tt’s water, you must make a brachah!’ ”

“And All Its Troubles”

Shanghai rabbanim proclamation, 1946

Rabbi Kolodny brings me a discovery on his desk — a proclamation by the rabbanim of Shanghai in 1946 calling for a “day of mourning and prayer in commemoration of Jewish victims of Nazi terror.” It was signed by every wartime Jewish leader there. Atop the list was Rav Meir Ashkenazi, Shanghai’s chief rabbi since 1926, followed by the Amshinover Rebbe — the typist rendered it as “Amshener” — and Rav Chaim Shmuelevich and Rav Chatzkel Levenstein of the Mir.

Part of that dossier contains newspaper filings of the conversion to Yiddishkeit by Setsuzo Kotsuji, the private tutor of Japan’s Prince Mikasa, Emperor Hirohito’s younger brother. The descendant of a long line of Shinto priests, he used his proximity to the highest echelons of government to convince them not to accede to German requests that Japan persecute its Jews. He was pivotal in Japan’s welcoming the Mir Yeshivah, first to Kobe and then to Shanghai, providing for their welfare and battling Nazi-inspired propaganda.

Kotsuji arrived in Israel in 1966, and at age 60 underwent a bris milah, taking the name Avraham. A picture in Time magazine depicts him in the hospital shortly after the bris, captioned, “Rabbis and Israeli government officials crowded around the open doorway as an elderly man was wheeled into the second floor of the operating room in Jerusalem’s ultra-Orthodox Shaarei Tzedek Hospital, where Mosaic law is observed so strictly that nurses are forbidden to write on patients’ charts on the Sabbath.”

Ultra-Orthodox. “That’s you,” laughs Rabbi Kolodny.

The article adds that Kotsuji became a full-fledged Jew, “with, as one rabbi put it, ‘all its rights and all its troubles.’ ” Kotsuji surely knew a thing or two about its troubles.

Strange Twists

Washington Heights Pirchei minutes, ca. 1930s

The archive also holds some of the strange twists of history.

When Henry Kissinger was President Richard Nixon’s national security advisor and secretary of state, he used those positions to browbeat Israel into making concessions that its leaders felt were dangerous.

But minutes of the Washington Heights Pirchei group that Kissinger participated in as a teenager, prior to his abandoning Yiddishkeit, show a surprising — and unreported — side to him. It depicted a young Kissinger arguing passionately that Yidden are not allowed to govern in Eretz Yisrael if it will not be run according to halachah.

The files also contain a devar Torah that Kissinger said on the subject of muktzeh machmas mi’us, or something that cannot be moved on Shabbos on account of its repulsiveness.

Legacy Media

Issue of the Jewish Observer, 1987

A copy of the now-defunct Jewish Observer from 1987 lay on a table. It was entirely dedicated to Rav Moshe Feinstein, the gadol who had just passed away a year prior.

“Rav Moshe. These two words meant all to each member of Klal Yisrael,” the article begins. “The wound is yet fresh for us.”

I don’t recognize most of the bylines, with the exception of Rabbi Labish Becker, currently Agudah’s executive director. I would not be lying to say that I am astonished when that voice from the past, Rabbi Becker in the flesh, walks in a couple of minutes later. He explains that he used to write book reviews for the Jewish Observer.

Even the advertisements call to mind a different era. There is an ad for “kosher fairy tales” that can be purchased “wherever Jewish records and tapes are sold.” The publisher insisted it was a “must for every Jewish home.” Mordechai Neustadt, the pioneer in sending shluchim to learn with Yidden in Soviet Russia, who passed away about three years ago, was advertising his Perfect Travel agency.

A hulking microfilm scanner looms in a corner, its size calling to mind the early computers. Shelves packed with microfilms — I estimate about a thousand — are piled high in a nearby closet, containing the tombstones of Orthodox Jewry’s first stabs at its own media. Names from newspapers of centuries ago are taped onto the cases. Here are the Machzikei Hadas newspapers in Poland; Rav Isaac Leeser’s The Occident from the mid-19th century America — it is labeled 1843-1857 — Dos Yiddishe Tagblatt from prewar Warsaw, the entire collection of Bais Yaakov journals from Lodz.

It appears that beginning from the mid-1800s, a vibrant Yiddish press competed for readers. Der Yid and Menorah in Warsaw, Hamodia in Poltava, Chassidishe Freint in Chernowitz, Der Yiddishe Shtime in Munkacs, Chassidishe Shtime in Krakow, Unzer Vort in Lomza, Halevanon in Paris and Mainz. A pile of LP records and equally antique cassette tapes of Rav Yaakov Kamenetsky, Rav Shalom Schwadron, and others lay in a pile.

A Piece of Cake

Chavatzeles report on Rav Shmuel Salant’s birthday, 1909

Rabbi Kolodny directs me to the microfilm machine — he wants to show me something he finds interesting. Rav Shmuel Salant, who served as Yerushalayim’s chief rabbi for 70 years until his passing in 1909, was niftar at age 93, and at his birthday several months prior, he was feted with a party and a cake decorated with icing, the Chavatzeles periodical reported. Rav Chaim Berlin brought the cake along with a poem, and the report indicated that the party took place annually.

Alongside kol koreis from rabbanim in honor of the upcoming shemittah year and advertisements for tea — “Don’t drink anything besides the Tea B-Brand, the beloved tea in Europe, America, Asia, Africa, and Australia” — we find the article. Terming him the Saba Kaddisha, the holy grandfather, the cover feature describes the attendees and activities at Rav Shmuel Salant’s final birthday.

And so it was, in its 39th year of publication, on February 3, 1909, Chavatzeles editors described in detail the rav’s simchah as front page news.

“Yerushalayim — On 2 Shevat, after midday, the greatest rabbanim and administrators of the mosdos of the holy city gathered in his home,” the article reports. “This year as well, a maaseh ha’ofeh” — a cake — “was sent by Rav Chaim Berlin, made in the shape of a tower and adorned with flowers, blossoms and decorations.”

No picture of the cake accompanies the article, but little is left to the imagination.

“This will make a splash,” Rabbi Kolodny predicts. “People say, ‘Oh, we only find a birthday in the Torah for Pharaoh.’ Here we see how the biggest rabbanim threw a birthday party for Rav Shmuel Salant, including Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, and they ate cake.”

Taking Care of Klal Yisrael

Letter from Mike Tress, 1957

“Do you know that there were rabbanim in Cleveland in 1854 who were talmidim of Rav Betzalel Regensburg — he’s in the back of the Vilna Shas — who had a get controversy with rabbanim in New York?” Rabbi Kolodny asks me. “There were tremendous talmidei chachamim there.”

The rabbanim of Cleveland had written a get, and their colleagues in New York questioned its legitimacy.

“He writes that the rav from Cleveland came with an Even Ha’ezer, he came with a Noda B’Yehudah, he has ksavim on Horius — he knows what he’s doing,” Rabbi Kolodny says with a laugh.

I expected to get the shivers when reviewing records of the Holocaust years. Instead, I get them when examining the files from its aftermath.

The Tress collection, stored in several thick binders, contain the mind-numbing stats of what went into the work of transplanting thousand-year-old communities, of restoring bodies and souls, of rebuilding a world of Torah on soil disparaged a few short years before as a treifene medinah.

“Please give bearer of this letter one 58” tallis and charge us,” one letter dated April 13, 1957, signed by “Michael G. Tress,” requests of the Chuster Tallis Manufacturing Company in Brooklyn.

The letter, in a way, encapsulates the Agudah mission that continues to this day — taking care of Klal Yisrael and Reb Yisrael, as Rabbi Moshe Sherer loved to say. The community as a whole and each individual separately. Mike Tress, who ran the Orthodox community’s largest organization, was signing letters for people, likely those who fled Hungary after the 1956 revolution, to get them a tallis — 58 inches across.

“This is to confirm,” says another letter, signed on March 19, 1957, by a Mr. Rosenberg from 116 Rutledge Street, “that I received a pair of tefillin.” A second letter confirms that he also received a tallis.

When Rabbi Kolodny began, it meant digging through files piled into huge, unlabeled boxes. “It’s said that 95 percent of an archive is junk and only five percent is needed. But you never know where the five percent is”

Future of the Past

At this point, Rabbi Kolodny has given the majority of his life to his beloved archive. He wants to retire. But the thought of what will happen to the files, photos, folders, and films endlessly occupies his mind.

Agudah, for its part, had begun digitalizing the archives, a project that is proceeding apace, and hopes to bring in another archivist to replace Rabbi Kolodny after he retires – although, say Agudah officials, his unique talents are quite irreplaceable. They hope to make use of his knowledge and special gifts in capacity as their consultant for many gezunte years to come.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 917)

Oops! We could not locate your form.