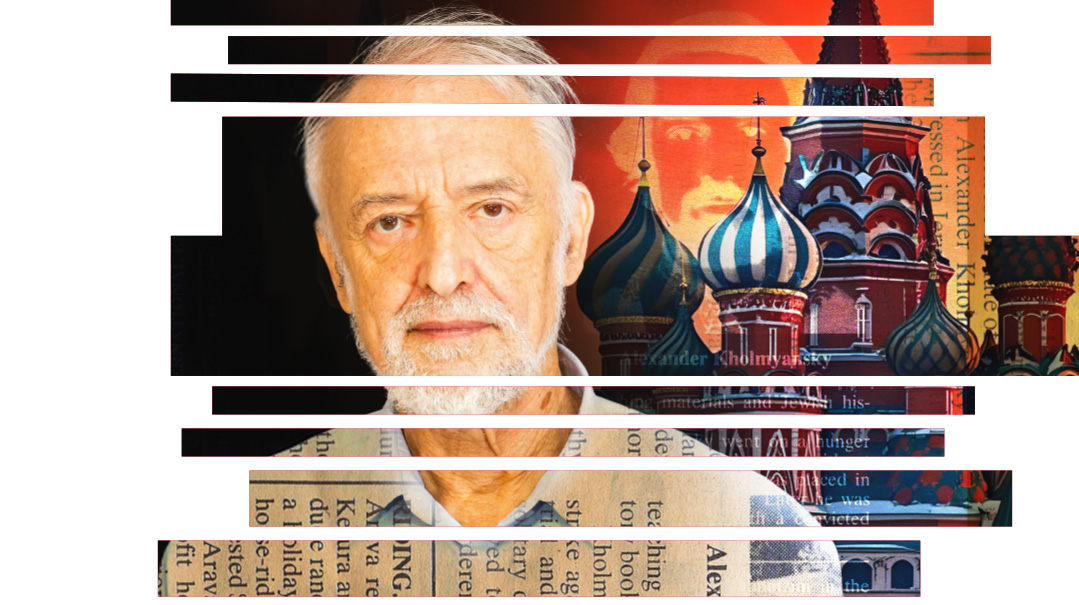

Underground Whispers

From his rat-infested cell, Ephraim Kholmyansky outsmarted his KGB captors

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, family archives

As a child in Moscow, Ephraim Kholmyansky knew nothing of his Jewish roots, but like so many others of his generation, a spark was somehow ignited. And not only did he learn Hebrew and Jewish observance, in the 1970s and 80s he headed a clandestine network of Hebrew teachers all over the USSR — until he was arrested and thrown into a rat-infested cell, where, during months of incarceration, he learned to outsmart his KGB captors

Võru, Estonia, July 1984

“Where do I take him?” the policeman on duty asked his superior.

“Take him to number one.”

The door of the nearest cell swung open with a grating shriek of metal, and a moment later, I found myself inside. The door slammed shut. Stunned, I stood there in the dark… Hashem yeracheim, the stench! This was a nightmare. I felt sick, unable to breathe. Suddenly, a wild rage seized me, and I began pounding furiously on the metal door, but to no avail.

It’s been 40 years since Ephraim Kholmyansky was arrested by the KGB on trumped-up charges. Kholmyansky, a computer hardware engineer who organized a massive network of Hebrew language and Judaic classes throughout the USSR, endured brutal conditions and psychological torture during his 18 months of imprisonment. But he did not only endure; he heroically defied his captors. With constant prayer, bitachon, and a keen understanding of the KGB’s psychology, Kholmyansky managed to beat the KGB at their own game.

How did someone who, growing up, was barely aware that he was Jewish, become such a passionate activist for Torah, Judaism, and Israel?

How did he run a vast Hebrew network in 20 cities across the USSR, right under the nose of the KGB?

And how did he manage to hold his own against the KGB even in the most inhumane conditions?

B

orn in 1950 in Moscow, Ephraim (then Alexander, or Sasha) Kholmyansky grew up with virtually no knowledge of Judaism. Hoping to shield their son from the anti-Semitism prevalent at the time, Ephraim’s parents never even told him he was Jewish. He discovered the secret by accident — through a government census survey — and was aghast to learn that he was part of the “mysteriously evil, sinister, and greedy” race that he associated with Judaism.

But after years of concealing his Jewish identity, Ephraim gradually began to take pride in his national heritage, though due more to its famous Jewish scientists than to the Jewish religion. In time, the idea of moving to Israel — where Jews could live freely as Jews — began to capture his imagination.

Today, his home in Maaleh Adumim outside Jerusalem is a world away from where that dream began: One day when his mother was cleaning his brother Misha’s room, he noticed in an open desk drawer a small, tattered booklet with Hebrew letters. Ephraim had seen Hebrew letters before, in an old prayer book left by his deceased grandfather. But this was different — it was a calendar in very small print, in both Hebrew and Russian, and it came all the way from Israel. So alien and remote, yet so full of hope.

After the 1967 Six-Day War, 17-year-old Ephraim’s heart was ignited. Like so many other young people across the Soviet Union at the time whose souls, cut off from their heritage for decades, slowly became aroused, his dream of making aliyah intensified. He and his family managed to tune into the Voice of Israel broadcast that announced Israel’s stunning victory, and he felt a growing yearning for that faraway Jewish land. But leaving Mother Russia, especially for someone in a profession that was considered “classified,” was nearly impossible. Although he opted to study computer engineering, he tried to stay under the radar with the lowest level of security clearance, hoping it would not be an obstacle to his dream.

In nurturing his dream of emigrating to Israel, Ephraim was determined to find himself a Hebrew teacher. “Of course, going to the main synagogue to ask about Hebrew lessons under the watchful eye of the KGB was not an option,” Kholmyansky relates. Young people weren’t even allowed into the synagogue, and only the old-timers were allowed to learn Hebrew. It took six months of discreet inquiries before he finally found someone who could teach him, and those studies soon led to an interest in Yiddishkeit as well, as his level of observance began to grow along with proficiency in Hebrew.

But Ephraim’s new avocation did not go unnoticed by his superiors, and one day he was summoned for a meeting with his department head. Ephraim had to do something to scotch the rumors, and thinking quickly, he “let it slip” to the biggest gossip at work that he was studying… Japanese. “Don’t tell anyone,” he added for good measure — effectively ensuring that everyone would hear about it with all due haste.

But Kholmyansky’s reprieve at work was all too short. After he received his letter of invitation from Israel, the first step in the emigration process, he had to gain clearance from his workplace — a much greater hurdle. As expected, Kholmyansky was ineligible to emigrate because of the “state secrets” he was holding — even though he had never touched a classified document in his life. “A man with your experience might glean classified information simply by overhearing his colleagues chatting in the hallway,” he was told. Moreover, from that point on, Ephraim became a pariah in his workplace.

Ephraim’s rebuff had an unexpected benefit, however. Ostracized at work, he threw himself into his Hebrew studies. He realized that this was an opportunity to teach others, and started with just one student — whom he warned would be his “guinea pig” for formulating his own teaching methodology.

Kholmyansky’s teaching opportunities grew, and he used everything from Agatha Christie mysteries he translated himself to simple Hebrew jokes to keep his students engaged. Printed material, however, was nearly impossible to come by.

“In offices and factories, copy machines were under the vigilant eye of the KGB,” Kholmyansky recounts. And so, Jewish activists had to resort to more creative means. “Most of the materials produced by the Jewish movement were photographed with a camera, then developed and printed on thick photo paper in home darkrooms, mostly in people’s bathtubs. People passed them around in secret.” When Ephraim managed to get a hold of 20 photocopies of a Russian-language brochure about the Jewish holidays, he was ecstatic.

By the late 1970s, a strong Jewish revival had started to take root in Moscow, but Kholmyansky realized that a majority of Soviet Jewry lived outside the two main cities of Moscow and Leningrad. These Jews had no Jewish infrastructure, and Kholmyansky decided to turn his attention to them. Logistically, though, this would entail a whole new level of organization: locating potential students, teachers, and materials on a much wider scale.

In 1979, Ephraim met with fellow teacher Yuli Kosharovsky in the latter’s apartment to start planning, but they couldn’t say much — the apartment, they knew, was bugged. So they communicated via a children’s erasable drawing tablet that could be quickly wiped clean in case anyone came knocking. They divided the USSR among the key Hebrew teachers, with Ephraim taking the southern part of the country, his brother Misha organizing classes in Leningrad and the Baltic states, and famed refusenik Yuli Edelstein — today a Likud MK and former minister and Speaker of the Knesset — in charge of Belarus. (Yuli Edelstein was then expelled from university, harassed by the KGB and local police, and found odd jobs as a street cleaner and security guard before his own arrest and brutal incarceration several years later.) Yuli Kosharovsky was in charge of managing their relations with Israel and Jewish communities abroad. They dubbed it “The Cities Project.”

One Step Ahead

Ephraim’s success in awakening Jewish identity did not go unnoticed by the KGB. Despite taking every precaution to evade suspicion, Kholmyanksy was called in for a “chat” with the district KGB officer in June 1980. The charge: “conducting anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda.” While Kholmyansky vigorously denied the charges, his interrogators told him that his longstanding application to emigrate would be denied, and that instead of leaving the USSR, he should familiarize himself with the Soviet criminal code.

That little conversation was just the beginning. More summons to the police began to arrive, first by mail and then in person.

“I began receiving anonymous phone calls. Heavy breathing in the receiver, vague threats such as ‘I wouldn’t stay out late if I were you… you never know what can happen.’ They would hang up and call back right away, several times in a row, alternating threats with the foulest curses,” Kholmyansky recalls. His apartment, too, was under constant surveillance. The mother and son who lived next door made no secret of their assignment — she sat perched on a stool in front of her door, watching anyone who came to visit the Kholmyanskys, while her son (a PhD student at Moscow State University) stood on the landing for hours pretending to read the newspaper.

Outside proved to be no better. When meeting with fellow activists or students in public places, Kholmyansky began to notice a trail of “uninvited guests” appearing each time. “As soon as we sat down on a bench, a guy in a jogging suit plopped down on the next bench.”

Undeterred by the KGB’s tactics, Kholmyansky developed strategies to continue teaching. He developed a code for arranging meeting times and places. He organized a list of meeting locations and assigned a number to each. When someone mentioned a location over the phone, the others would know to arrive at the place of the next number on the list. As for times, a coded conversation might go something like this:

Felix Kushnir, a fellow activist: “Hey, are you coming tomorrow night?”

Ephraim: “I think so.”

Felix: “What time?”

Ephraim: “Oh, I don’t know, maybe eight or nine — I’ll have to see how it goes.”

This meant that they should meet today at five (minus three hours from the time mentioned).

Ephraim also had to cope with the challenge of storing vast amounts of material under the nose of the KGB. Anything relating to the Cities Project would immediately incriminate him as well as his fellow teachers. Ephraim encrypted the most vital information on a small, thin piece of paper which was alternately kept between the leaves of a book in his bookcase, or in a secret pocket of his clothes. If all else failed, it could easily be swallowed. Other second-tier information was kept by Ephraim’s mother or with loyal colleagues, and often changed hands.

But finding couriers to send materials to teachers across the USSR was another headache. In 1981, when he was scrambling to get materials to a new teacher in Moldova, someone suggested a potential courier, a young woman who was known to be trustworthy. Her name was Anya Yerukhimovich; she was not currently involved in any Hebrew activities, and thus not likely to be on the KGB watch list. In time, Anya would become Ephraim’s wife.

Despite the constant cat-and-mouse game with the KGB, Ephraim managed to organize a summer Hebrew camp for adults in Estonia in July 1984. The full-fledged immersion in Hebrew studies worked its magic.

“A few days in, and I could already feel the change,” he says. “The students were absorbing the material, speaking more fluently and freely, and their eyes had acquired a special gleam.”

The camp grounds, nestled between dense trees in a holiday village, seemed ideal, as it was far from the eyes of the KGB. The only other tourists in the village were a friendly middle-aged man and a group of truck drivers who were usually drunk and never bothered Ephraim’s group.

On Monday, July 22, everything came to a crashing halt. At 7 p.m., a policeman, accompanied by two men in civilian clothes, burst into the camp building. With the flimsy excuse that a flower bed had been vandalized nearby, they searched the premises for the next seven hours. And with the suddenly sober truck drivers waiting to take the group to police headquarters — to be questioned by none other than the middle-aged “friendly tourist” — it soon became clear that the KGB had known about the camp all along, and was just waiting for the opportunity to pounce.

But while Ephraim’s students and fellow teachers were released soon after their interrogations, he faced a different fate. Barely ten minutes after returning to the camp, a burly police officer and soldier showed up, claiming that Ephraim needed to return to headquarters that night to fix some irregularities in his ID papers. Arriving at the police station, Ephraim’s belt and shoelaces were forcibly removed, and he was shoved into a dark, fetid-smelling cell. A chorus of scratching and gnawing noises — indicating the presence of hungry rats — added to the horror scene. This was Ephraim’s initiation to what would be an 18-month prison sentence.

Stare Down Your Fear

Transferred to a detention facility in Tallinn, Ephraim soon realized that he wouldn’t be released anytime soon. The allegations became much more serious — from vandalizing a Soviet flowerbed in Estonia, he was now accused of concealing a cache of weapons and anti-Soviet literature in his family’s Moscow apartment. This last charge was also a fabrication — Ephraim’s mother, who was present during the house search, witnessed how the KGB agents “found” the weapons, which they had planted under a bookcase.

To ramp up the pressure, Lieutenant-Colonel Chikarenko from the major crimes unit arrived from Moscow and took over Ephraim’s interrogations. But Ephraim, who was 34 at the time, was no novice to KGB tactics and refused to be manipulated or lose control.

In fact, Soviet Jewish activists often hashed out the best way to conduct oneself during a KGB interrogation. One school of thought was to answer the interrogator’s questions, but to ignore any of his attempts to get off-topic — a typical ploy of the KGB to gather incriminating information. Another school of thought was to speak as little as possible during the interrogation.

“The point was to show the KGB that they’d get nothing out of you, so they would give up and perhaps not summon you again,” Kholmyansky explains.

But after considering both methods, Ephraim came up with his own — which the KGB soon learned to recognize as his trademark when his colleagues and students were brought in for questioning.

“My approach was to talk in blocs of words, preferably repeating them, not varying the subject and the words too much.” Repeating completely illogical statements, such as, “Decent people don’t talk to ladies in that tone!” was part of his tactic for getting the KGB to back off. Ephraim knew from experience that it was impossible to remain completely silent during an interrogation, but realized that staying strictly within the topic was extremely difficult — so this was a hybrid method that was doable yet revealed little information.

Oddly enough, Ephraim also advocated admitting to the interrogator that you were afraid of them. “Hearing the words ‘I’m afraid’ tended to annoy the investigators a great deal, because they knew perfectly well that anyone who recognized his fear enough to actually describe it wasn’t all that frightened or intimidated,” Ephraim says. “It meant he was self-aware, he was resisting, and therefore he hadn’t broken. Plus, threats and intimidation were officially prohibited by the code of criminal procedure, and even though the KGB acted as though they were above the law, they liked to play lip service to it.”

Bearing all this in mind, when tasked with filling out his testimony, Ephraim did so — but not in the way Chikarenko expected. “I affirm that I did not keep arms, ammunition, or anti-Soviet literature at home,” he wrote. Ephraim refused to answer questions about the summer camp, as they were irrelevant to the charge against him.

Still, Chikarenko wasn’t cowed. He hinted that Kholmyansky could face five years’ imprisonment for illegal weapons possession, plus more for the anti-Soviet literature if he didn’t cooperate with the investigation.

“Nothing good will come of being stubborn. We’ll chat again soon,” Chikarenko said as he ended the interview.

At that point, with a fabricated charge and looming sentence against him, Ephraim decided to declare a hunger strike.

“They wanted to break me and use me as an example to intimidate all the other members of the Jewish movement, so that everyone would give in and stop resisting,” Ephraim says, explaining his motivation at the time. This was his way of fighting back – to show that he rejected their false charges, and to give hope to his fellow Jews behind the Iron Curtain. “True, I would suffer, but so would the KGB. I was ready.”

Suffering was not long in coming. Realizing the potent PR power of a hunger strike, the KGB was determined to end it at all costs. Kholmyansky was thrown into the punishment cell. “‘Make yourself at home,’” the guard gestured, as he clanged the door shut.

“I found myself in a stone pit. The guard lifted a cot — made of bare planks held in a metal frame, with no bedding on it — and pressed it flat against the wall. A metal pin was pushed through from the outside, locking the cot tightly in place.”

Ephraim’s new “home” was a tiny, freezing cell with room to walk two steps in each direction. There was no place to sit down. The only reprieve was from 11 at night until five in the morning, when the guards opened the cot. For the remaining 18 hours of the day, even sitting on the cell floor was off-limits.

“‘Don’t ever lie down on the cement floor,’ the zeks [fellow prisoners] had told me,” Ephraim remembers. “‘You’ll catch tuberculosis right away. Whatever you do, don’t lie down.’” Ephraim spent more than four months in that cell, from September 14, 1984, until January 30, 1985. Much of that time was spent standing, alternating positions and telling himself Chekhov stories to pass the hours that ticked by with excruciating slowness.

One More Hour

Shabbos was a particular challenge. Ephraim, though, was resourceful. Deciding that some interior decorating would go a long way toward creating a Shabbos atmosphere, he would prop three nice postcards from the prison store against the wall, and would wash out the cell with an old rag. Then he’d sing whatever he could remember from Kabbalas Shabbos and zemiros.

“My singing was far from perfect,” he recalls, “but still I felt as if the space above my head had opened up, reaching all the way up to the Source of Holiness, and energy flowed down to me — an encouraging, nurturing, uplifting sensation that gave me hope and support.”

News of Ephraim’s hunger strike soon got around the prison and gave him celebrity status. Fellow prisoners began to slip him old newspapers and rags — gifts, which in prison currency, were invaluable for insulating his freezing cell. Some of the guards also became more compassionate — occasionally letting his cot remain in the open position for longer, so he did not have to remain standing for 18 hours a day.

But one of the biggest boons of the hunger strike was that he finally found a way to communicate with his family. A few days into the strike, a passing prisoner whispered into Ephraim’s cell: “Hey, you want to get a note out to the outside?” Ephraim was incredulous — how was it possible? The fellow prisoner gave him two minutes to scribble and address a note home, and instructed him to squeeze it through a crack in the upper right corner of the door. His new friend knew of a transport leaving that day, which would be able to get the letter out.

But while Ephraim’s status improved among his fellow inmates, it took a sharp turn for the worse with the prison administration. Initially, they tried to end his hunger strike by improving his living conditions — leaving his cot down full-time, and even giving him sheets and blankets — so they could threaten to take those privileges away if he didn’t cooperate. But when that didn’t work, they ramped up the pressure. Ephraim was moved to a new punishment cell — this one encased in metal walls.

“I felt as though I were sitting inside a refrigerator, freezing from the inside,” Ephraim remembers. “It was a cold death chamber.”

Ephraim spent just three days in this metal cell, but his physical condition deteriorated drastically during that time. His hearing, sight, and coordination all became markedly weaker — much to the KGB’s delight. “Kolk and Mailboroda, the warden and his deputy, kept staring at me during our endless meetings, wondering if I was near the breaking point and one last push might tip me over, make me give up,” Ephraim says. But even in his weakened state, he refused to give up his hunger strike or admit to the false charges.

When he was dragged to the prison hospital where he was force-fed, his weight was just 42.5 kg (93 pounds).

Incredibly, Ephraim not only refused to yield to KGB threats, but he also demanded just treatment. Force-fed via a feeding tube according to prison regulations, Ephraim protested to his interrogator when one particular nurse shoved the tube mercilessly down his throat. Two days later, the nurse was gone. And when Ephraim was informed that he would be moving to a new cell, only to discover it contained the most awful smell — with flies buzzing around for extra effect — he refused to step foot into it.

“Are you refusing to obey a direct order?” Litvinov, the block commander, hissed furiously.

“You can do whatever you want, kill me, hang me, but I’m not going in there.”

The block commander, shocked at being challenged by a prisoner, started yelling at nearby prison cleaners to scrub the cell. “I made them wash it over and over again, until all the visible filth was gone before I would enter the cell,” Ephraim recalls.

The horrors of Ephraim’s imprisonment produced some humorous moments, too. Ephraim’s family knew of his hunger strike from the letters he managed to smuggle out, and were desperate for updates regarding his health. They knew that the prison doctor was an elderly Jewish woman, and felt sure that she would help them — if only they could find a way to make contact with her. Ephraim’s father, Grigory (Grisha), decided to take matters into his own hands. Dialing the prison’s front office from a telephone booth, Grisha asked for the doctor’s telephone number.

“Who’s asking?” demanded the soldier on duty.

“Andreyev!” Grisha barked into the phone.

“Andreyev” was, in fact, a figment of Grisha’s imagination. Ephraim’s mother Rosa recalled her reaction when her husband identified himself on the phone: “He sounded just like a big boss, angry that people didn’t immediately recognize his voice,” she remembered. “The Soviet mind is programmed to obey the commanding shout of a superior without question. The Estonian soldier couldn’t be sure this wasn’t, in fact, some big boss in his own chain of command.” The doctor did speak to them a bit, and they were able to get occasional updates on Ephraim’s condition.

And his condition was dire. “It was getting harder to open my eyes and to keep them open,” Ephraim remembers. He was so weak he could barely concentrate, but he knew that he must not give up his hunger strike — doing so, he felt, would be a major defeat for Soviet Jewry.

“There were several times that I felt I couldn’t endure anymore,” Ephraim relates. “But each time, something happened that gave me the encouragement to continue. There was this internal dialogue where I told myself, ‘I cannot continue, cannot endure anymore.’ And then I’d tell myself, ‘That’s correct. You did a magnificent job. Could you please endure one hour more? And then one hour more?’”

Free to Be

Ephraim’s trial was scheduled for January 1985. He was shocked to discover that he was permitted a family-appointed lawyer.

“The very concept of defense, of fair trial, seemed utterly alien within these thick, lifeless walls, in this world of lawlessness and oppression,” he recalls. At the first meeting with his kindly lawyer, Mart Rask, Ephraim was so shaken that he began to cry.

At the trial, though, he was completely in control. He vigorously denied the charge of storing weapons in his Moscow apartment, and exposed many procedural violations that had been committed during the “search.”

Ephraim and his family waited with dread for the verdict and sentencing — “seven years of imprisonment plus five years of judicial deportation” — that hung like a sword over his head. But the publicized hunger strike, combined with Ephraim’s many tefillos, had accomplished something. The final verdict was surprisingly mild: one year and six months imprisonment. For Ephraim, as well for his grassroots supporters, it was considered a victory.

Even with an end in sight, Ephraim faced many new hurdles in his remaining year of imprisonment (he’d already spent six months in prison by the time of the verdict). Transferred to a Siberian labor camp, Ephraim was forced to join a work gang in his emaciated state. Although his job — weaving giant mesh bags by hand — didn’t seem inordinately difficult, Ephraim soon realized that it was an impossible task. His fine motor skills and coordination had completely deteriorated from his monthslong hunger strike, and he could barely finish half a bag out of his daily quota of six. And to complicate matters, Ephraim was determined not to work on Shabbos — which would only be possible if he fulfilled more than his quota during the rest of the week. But with a combination of bartering goods from home for fellow convicts’ extra bags, and making friends who were willing to help out, Ephraim managed to meet his daily quota — and stash away an extra bag each day so he would not have to work on Shabbos.

On February 2, 1986, Ephraim was finally released. Greeted by his family and fiancé Anya Yerukhimovich — with whom he had corresponded while in the labor camp — Ephraim lost no time in acknowledging the Source of his newfound freedom.

“I know that You made this miracle, that You gave me the stamina to endure, to overcome, to withstand things that were utterly beyond my humble human abilities,” he told G-d straight out. Months later, after he recovered, Ephraim and Anya were married in his Moscow apartment.

After leaving prison, Ephraim continued his activism. He lobbied for the release of Yuli Edelstein (who had been imprisoned on fabricated charges of drug possession and sentenced to three years of hard labor) and for the release of other refuseniks, and actively promoted Jewish emigration from the USSR, even as his own application was continuously refused. Even a cadre of top-tier politicians and diplomats — including famed British historian Sir Martin Gilbert, Massachusetts Senator Edward Kennedy, US Secretary of State George Shultz, and Israel’s UN ambassador Bibi Netanyahu — failed to secure his release.

It took two more years until Ephraim realized his years-long dream. In January 1988, he, Anya, and baby Dora boarded a plane to Eretz Yisrael. Among the many triumphant greetings and special moments, perhaps the most meaningful was Ephraim’s first visit to the Kosel.

“My cheek pressed into its rough surface,” he recalls. “Only a little while before, this cheek had pressed into the rough wall of a punishment cell.”

With the fall of the Iron Curtain, Ephraim began to help the wave of new immigrants from the Soviet Union, a position he was offered by Israel’s Education Ministry. Later, he worked for a number of startup companies, and he currently works with a company that’s involved in testing the antiviral qualities of cinnamon. Anya works as a computer programmer for the Central Bureau of Statistics. They have two daughters and three sons, the youngest of whom learns in the Mir yeshivah in Jerusalem.

Three years ago, at the age of 71, Ephraim finally published his story. Called The Voice of Silence: The Story of the Jewish Underground in the USSR, the memoir is a document to the decades of resistance, as well as a tale of Divine kindness. When asked why he decided to write it, Ephraim replied that he was just the conduit to reveal Hashem’s miracles.

“And you know,” he continues, “there have been quite a number of memoirs written by former Prisoners of Zion, and while some of them are written primarily as material for historians, I wanted, as much as I could, to reach a wider readership, to invite the reader to be part of this incredible period where we saw the Hand of Hashem in the entire chain of events.

“You know, people still ask me, ‘Was it worth all those years of suffering?’ And the answer is yes. I’m a happy person. My dreams came true. I did impossible things and I saw the Divine blessing. Who could ask for more?”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1040)

Oops! We could not locate your form.