Between Bohemia and Moravia there were about 400 shuls in the country at the turn of the 20th century 60 of which were eventually burned by the Nazis. Yet today in the entire Czech Republic there are only four functioning shuls — three in Prague and one in Brno the Czech Republic’s second-largest city. What happened to the rest?

W

e had spent a few days in Prague seeing the classic Jewish sites — shuls cemeteries and museums that showcase the rich and lengthy Jewish presence in the city. We met some members of the current Jewish community our 13-year-old was privileged to lead Shabbos Minchah in the Altneuschul — which may be the oldest shul in continuous use — and we took in Prague’s famous zoo and other sites. But chances are you’ve also visited or read about Prague and don’t need our account of this ancient and now-popular tourist city to enlighten you.

Indeed Prague was the sideshow to the main point of our trip to the Czech Republic with my wife’s extended family. Her father a Holocaust survivor shared his story with all his descendants at the Theresienstadt concentration camp where he was held for a year and a half during World War II. We thus spent a very moving day in the once German-occupied Terezin where much of Czech Jewry was killed or sent onward from there to almost certain death. And once in the area how could we not explore the expansive Czech lands through a Jewish lens?

The Czech state today comprised of the regions Bohemia Moravia and Czech Silesia was originally formed in the late ninth century and over the subsequent centuries was under the rule of a series of kings the Holy Roman Empire and the Austrian Empire. In 1918 following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after World War I the Republic of Czechoslovakia was formed. But it was occupied by Germany in World War II and then afterward fell under the Soviet sphere of influence and eventual occupation.

Finally in 1993 on the heels of Communism’s demise and the country’s 1989 Velvet Revolution Czechoslovakia peacefully split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Although there were always Jews in Bohemia and Moravia numbering up to 120 000 before the Holocaust there are only about 4 000 today (most of whom are in Prague). But testimony to the rich Jewish past remains and we wanted to investigate the history with our own eyes.

Neighbors Forever

Our first stop was Nikolsburg also known as Mikulov close to the Hungarian border in southern Moravia. The name conjures up some of the greatest luminaries of the previous centuries including the Maharal (who was the rav of the city for 20 years before moving back to Prague) the Tosafos Yom Tov Rav Mordechai Benet and Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch (he was the city’s rav for five years before moving to Frankfurt). One of the city’s most famous rabbis was Rav Shmelke of Nikolsburg (1726–1778). Originally called Shmuel Horowitz he spent time learning with the Baal Shem Tov’s star disciple the Maggid of Mezritch and became one of the greatest of the early chassidic rebbes. Today’s chassidic groups of Nikolsburg and Boston are descended from him.

In many ways Nikolsburg still looks as it did hundreds of years ago. The local shul the only extant one of 12 that had graced the town has been renovated twice and serves as a tourist site and a small museum of the local Jewish history. A short distance down the block stands Rav Shmelke’s yeshivah building and a further two-minute walk brought us to the town’s historic cemetery where we stood facing the graves of Rav Menachem Mendel Krochmal (d. 1661) Rav Shmelke (d. 1778) and Rav Mordechai Benet (d. 1829) one next to the other. With so many years separating each of them we wondered how that happened. In fact it was no simple matter.

Before his passing, Rav Shmelke requested that he be buried next to Rav Menachem Mendel Krochmal — a prior rav of Nikolsburg from the previous century, student of the Bach, and author of the (original) Tzemach Tzedek. As Rav Shmelke’s grave was being dug, an old man approached the chevra kadisha and said that he remembered hearing from his father that he had heard from the Tzemach Tzedek himself that no one should be buried next to him. Now, 117 years later, the chevra kadisha was in a quandary — this man and his father were both known as trustworthy, upstanding members of the community, which was thrown into turmoil not knowing whether to heed the wishes of the earlier sage or the recently deceased rebbe.

Before coming to a decision, they decided to open the archives of the chevra in the hopes of gleaning some direction. Maybe there would be some record of what the Tzemach Tzedek had said. Indeed, they found that the Tzemach Tzedek had left instructions that no one should be buried next to him — until a certain date. And that day was the very date!

Fifty-one years later, another burial saga took place in Nikolsburg. Rav Mordechai Benet, the longtime beloved but overworked chief rabbi of Moravia, centered in Nikolsburg, was already in his late 70s in the summer of 1829 when he traveled to the spa town of Carlsbad for treatment — where he passed away. As transporting bodies at that time was no trivial matter, the Lichtenstadt Jewish community decided to bury this well-known tzaddik in their cemetery. But that wasn’t the end of the story.

A huge fight ensued, involving many of the leading rabbis of the time: the Nikolsburg kehillah demanded the return of their rav’s body and Lichtenstadt, supported by the beis din of Prague, argued that a body is not exhumed once buried. On the “Nikolsburg side” were Rav Akiva Eiger and the Chasam Sofer — one of Rav Benet’s greatest admirers — who wrote a lengthy, complex teshuvah filled with superlatives describing Rav Benet and permitting his reinterment in Nikolsburg. Seven months later, he was in fact brought to rest in the city he had served with devotion.

Fossilized Ghetto

We left Nikolsburg with a taste of what these lands had to offer — a shul that looks like a museum, a cemetery full of luminaries, and a ghetto still fairly intact. But all with no Jews.

There was once a time when Jewish ghettos and shtetls were spread across much of central and eastern Europe, but today, most of them are gone without a trace. There are a few cities, though, where the ghetto stands as it did a hundred years ago (minus the Jewish inhabitants), an echo of a bygone era. One such town is Boskovice. A quaint village of about 12,000, it once had one of the oldest and largest Jewish communities in Moravia. Arriving after dark, we found a charming old mill converted into a hotel, which had room for us to stay. With its high ceilings, no elevator, and still-turning watermill on its grounds, it was a presage to the old-world ghetto we would visit the next day.

Jews settled in Boskovice in the 14th century, and the ghetto we saw, with its winding alleys and old buildings, was likely established about 100 years later. The town was home to a famous yeshivah, and it is known that in the mid-19th century, the 2,000 Jews in the city were a third of the population. Yet only 14 local Jews survived the Holocaust, and while they briefly attempted to revive the community, it no longer exists.

The ghetto, also referred to as the “Jewish Quarter,” has become a significant attraction for tourists, who can follow a map showing 27 different buildings and landmarks along a walking trail. The fact that so much has been preserved is quite surprising, considering the town’s history of fires (in 1823 over half the town burned down) and plague.

The last stop on the walk leaves no doubt that this was once a ghetto, and not merely a Jewish neighborhood — the original ghetto gate, which was locked nightly. On the way, we passed several ancient residential buildings, the former house and yeshivah of the town’s rabbi, Rav Shmuel HaLevi Kolin — author of the Machatzis Hashekel, the butcher (and slaughter?) house, an iron bar marking the ghetto boundary, and a distillery.

What is not mentioned in the guide booklet are some of the smaller finds that piqued our interest. One of the un-renovated original private houses had a mezuzah klaf still tucked in a niche dug out in the stone doorpost. On one renovated house, the new owners must have noticed the mezuzah, because they reaffixed it — albeit upside down and too high. Above the doorway of another house was a plaque with the Hebrew words, “Shachor al lavan — zecher lachurban 5592/1832.” The curators assume that this is related to the reconstruction following the 1823 fire, although in our mind, it is certainly possible that it was a standard zecher l’churban for the Beis Hamikdash.

Another building sported a large sign with a picture of a white-bearded, black-hatted rabbinic figure and the words “Rabinuv Senk” — which means “Rabbi’s Bar.” After making a l’chayim, tourists can step into an eatery named “Makkabi,” with menorahs and Magen Davids on its sign (a poor substitute for a kashrus certificate, but it doesn’t seem to hamper the tourist business).

For us, one of the highlights was the mikveh. Located in the basement of a house that does not seem to have been renovated in years, but which is occupied nonetheless, the pool still contains flowing water and most likely could still be used.

On the edge of town is the large cemetery of about 2,400 tombstones in fairly good condition — the most famous of which is that of Rav Shmuel HaLevi Kolin. Another is of Rav Avraham Placzek, who succeeded Rav Samson Raphael Hirsch as chief rabbi of Moravia and was considered one of the leading halachic authorities of the time.

Not all cemeteries in the Czech Republic have fared as well. Many have no oversight and are in a state of total disrepair; others were intentionally destroyed. While the classic tours in Prague include the historic cemetery in the old city that contains the grave of the Maharal, fewer tours venture out the mere three further metro stops to the Old Jewish Cemetery in Zizkov (used from 1680–1890) to see the graves of Rav Yechezkel Landau (1713–1793, author of Noda B’Yehuda) and many tombs with unusual drawings that reveal something about the interred person’s life.

Yet while the tombs have survived, much of the cemetery itself hasn’t. Zizkov Tower, a skyscraper with a restaurant observatory and huge statues of babies scaling the sides (and dubbed one of the world’s ugliest buildings), sits on part of that cemetery. To build it, they simply dug up the cemetery, with stone and bones being tossed about. The workers apparently found a few of the tombstones interesting and made some sort of monument out of them. On another section of the cemetery now sits a miniature golf course (and all this, in a large city with an identifiable cemetery and a continued Jewish presence).

Writing on the Wall

Unquestionably, the main site in Boskovice is the shul. Called the Synagogue Maior, it was built in 1698 and over the years underwent expansions and repairs. What makes it so unusual is that the interior walls are covered with Hebrew inscriptions of biblical verses and numerous prayers. This is not your typical shul with a poster containing Modim D’rabbanan. Rather, its arches and walls are covered with exceptionally decorative paintings and liturgical texts.

The painted shul in Boskovice was not totally foreign to us. On our visit to Theresienstadt concentration camp, we davened Minchah in the “hidden shul” of Terezin, with its walls adorned with texts — including a particularly poignant “Mimaamakim kerasicha Hashem.”

Rav Meir Eisenstadt, also known as Rav Meir Ash (d. 1744) was a highly influential posek, well known for his responsa Panim Meiros, as well as for his most famous student, Rav Yehonasan Eybeschutz. He discusses (Panim Meiros 1:45) a question he received from the Moravian town of Prost?jov (25 miles from Boskovice) where he was rabbi from 1701 to 1711. They had a shul whose walls contained prayers that included G-d’s name, and the townsfolk desired to plaster the walls and paint over them with nicer works. In a tour de force of sources and reasoning, he explained how and why he permitted the plastering. Already in the early 18th century, this seems to have been a common way to “decorate” a shul in Moravia.

Our research indicated that if we were impressed with the painted shul in Boskovice, we’d really appreciate the one in the more remote but larger town of Trebic. This Moravian town of 40,000, located on the Jihlava River, had hosted Jews since the 14th century (and made up half the population in the 1600s), and its well-preserved Jewish quarter is a significant tourist site — although the few surviving Jews who returned after the Holocaust were gone by 1952, when it became a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Having already seen a ghetto in which tens of former Jewish buildings such as the Jewish council, the rabbinate, hospital, poorhouse, school, and many homes, are still standing minus the Jews, we were mostly interested in the main shul. Winding our way through the extremely narrow streets of the picturesque old town (where we received a parking ticket that the local police later forgave), we found the shul and were awed by the painted interior.

In Boskovice, some of the painting had been restored, but here in Trebic it was original — where whole sections of the davening were painted on the walls, and the utter variety and quantity of painted texts was staggering. Of course, there were typical pesukim and tefillos. But then there were also more obscure texts, such as the Keil Melech introduction to Selichos, and even the text of vidui ma’aser — what would that be doing in a shul in Moravia?

The Trebic shul building also contained a Holocaust memorial to the Jews of the town who were murdered and a museum of Judaism, but it was a strange feeling seeing on display how you live your life as if you were some ancient dinosaur. There was a “Shabbos room” with a set table, plastic challah, and candles; a holiday room with details down to the pretty hamantaschen. And on it went. Truthfully, it was done tastefully, and the women running the museum and tours were pleasant, well-educated, and competent. And without this museum, the majority of people who come will never meet a Jew or know anything about Judaism. In fact, all those we met there, both the guides and tourists, were thrilled to meet a “real Jew.”

Several years ago, while renovating one of the nicer hotels in Trebic, workers came across what was thought to be the remnants of the town’s mikveh. We wanted to see it for ourselves, and the gracious front desk clerk walked us down to the basement to see it. Although we couldn’t tell for sure, we know that there are surely remains of many old mikvehs all over the country.

Untouched Reminders

Between Bohemia and Moravia, there were about 400 shuls in the country at the turn of the 20th century, 60 of which were eventually burned by the Nazis. Yet today in the entire Czech Republic there are only four functioning shuls — three in Prague and one in Brno, the Czech Republic’s second-largest city. What happened to the rest?

Some, including the ones we saw, had been reconstructed to look like their former selves and serve as museums and Jewish cultural sites. Others are part of the “Ten Stars Project,” an €11 million project commissioned by the EU in 2010 to restore and highlight synagogues in ten towns around the Czech Republic. Some former synagogues are used as churches, municipal buildings, concert halls, libraries, schools, and museums. Others, especially in rural areas, have been turned into private houses, apartments, storage facilities, fire stations, shops, or even discos.

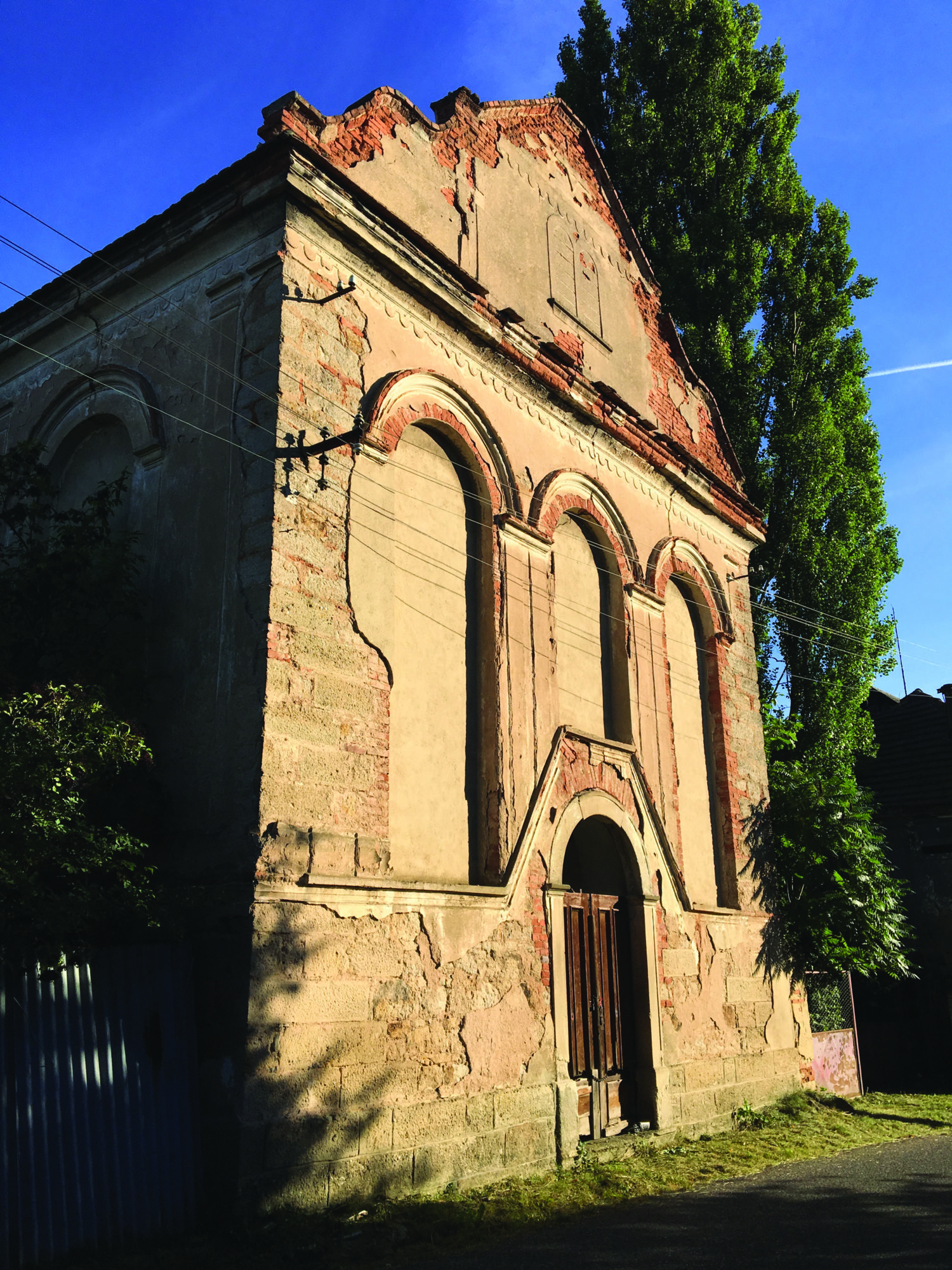

But what about all the defunct shuls that are neither rebuilt as shuls nor transformed for another use? Where are they? What do they look like? While the restored shuls look magnificent and enable us to envision the glory days of those communities, there is a feeling of something fake, something artificial. These shuls are the remnants of once-vibrant communities that were obliterated, but our goal was to find a churvah, a shul that had not been tampered with.

As part of the search we came across two amazing Wikipedia websites, one entitled “a list of Jewish monuments in South Bohemia” and the other “a list of Jewish sites in the Central Region [of the Czech Republic].” The list of synagogues and cemeteries is truly staggering; one can spend weeks crisscrossing the region visiting nothing but cemeteries and former shuls. Every entry on the list includes a statement about the current condition of the site, its precise location, and often a photo.

We were curious who was doing all that work, and eventually tracked down the responsible person, a devoted woman named Jitka Erbenov?. Her daytime job is English lecturer in the University of South Bohemia in ?esk? Bud?jovice, a major city that no longer has a shul. A non-Jewish married woman in her mid-30s with a teenage son, Jitka speaks excellent English, and for the last five years she has been devoted to documenting the Czech “Jewish monuments” using a Wikimedia sub-grant she initiated. A team of volunteers help upload material to these websites, while Jitka has taught herself the Jewish history of the region and travels around with her camera and laptop noting the current state of old synagogues and cemeteries.

Jitka knows of no Jewish roots in her family tree, and knew no local Jews until she got involved with this project. She began simply taking photos for Wikipedia, specialized in Czech villages, and after coming across some Jewish cemeteries, felt a sense of sorrow at the general absence of knowledge about the Jewish community that had for centuries been part of Czech history. Although her son and husband don’t usually travel with her, her husband bought her a book about Jewish history, and she has made an effort to learn about Jews, Judaism, and Israel.

One place Jitka helped us explore was a tiny village that appeared to have an untouched shul and a cemetery. Zderaz, located about an hour west of Prague, has a population of 275, average age of 40, and no Jews. But like so many of the towns and villages dotting the rural landscape, Zderaz did once have a Jewish community. Just finding the town was no easy feat, but once we were on its main — really only — street, finding the shul was no problem. It was a large building with two “luchos” adorning the front, and had clearly not been visited or cared for in decades. The locks were rusty and the property surrounding it heavily overgrown.

In such a small rural village, we tried to envision what this community must have been like. It was clearly agricultural and seemed far from wealthy. And there is no question that the financial and physical efforts that went into constructing the shul were a demonstration of the kehillah’s deep commitment to their Jewish heritage.

Jitka did her best to find the owners of the property for us. She contacted the mayor of the nearest large town, Kolesovice, and was informed that the shul was privately owned by an individual living elsewhere, with no contact information available. However, the owner’s brother lives next door to the shul, and Jitka was given the phone number of the company where he worked. The next day she actually called the company for us, but the brother was no longer employed there. Despite having the name of the owner and his brother, we were unsuccessful in finding anyone who could grant us access.

Determined not to leave without seeing the interior, and offering what might be the last tefillah to be recited within, we cased the joint for its weak point. While some of us methodically attempted to use logic, our 19-year-old used his brawn. Making his way through the thorny thicket, he was able to untwist heavy metal ties holding closed a courtyard gate, permitting the rest of us to enter.

Indeed, this was no beautified corpse. Dusty and neglected, with nothing of its original furnishings remaining, this shell of a shul boasted a two-tiered balcony for the women and a men’s section that probably held 80 people. The structure had gone through several phases since it was used as a shul. At one point it seems to have been used as a storage facility, and subsequently, it looks like it housed a vagabond.

Tucked in a corner on the second balcony were a few pieces of the mechitzah with metalwork Magen Davids. But there were no Jewish books or even mezuzahs to be found on the premises. Where the aron kodesh had once been attached, someone had the gall to graffiti a cross. We made sure that subsequent visitors would not find that cross. The least we could do was recite a silent prayer, document the state of affairs, and reverentially close the doors behind us.

Our next step was to find the cemetery. We continued on to the country road that meandered through the plowed fields, and midway to the next town, several hundred meters off the road, our daughter spotted what looked like an oasis. Surrounded by a stone wall and with trees growing within, the Jewish cemetery stood out in the flat, open field. A ten-minute walk off the rural road led us to a gate of this poorly tended but largely intact cemetery. Most of the gravestones were faded and difficult to read, but seem to date from the 18th to the 20th centuries. The most recent tombstone that we could find appeared to be dated shortly after the Holocaust, indicating that either someone had survived and returned, or a native had requested to be buried in her hometown.

We left intrigued, feeling connected to the town, wishing to know more about the individuals who lived there — but despite great effort, we’ve come up mostly empty-handed. According to the 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia, the Zderaz Jewish community, known then by its German name Dereisen, together with its six smaller (!) neighboring villages, had 213 Jews, its own synagogue, cemetery, and chevra kadisha, but no local educational institution.

The International Jewish Cemetery Project of the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies notes that the earliest known Jewish community in the town was in the mid-17th century, when the existence of a prayer room was recorded. The peak seems to have been around 1893 when there were 238 Jews there. That number rapidly declined as Jews made their way to larger cities — such that by 1921, the Jewish population was down to three, and the last Jew was gone by 1938. The Cemetery Project notes that this cemetery has indeed been frequently vandalized, but due to its secluded location, it is essentially impossible to protect. There seems to be no current care, although locals did clear vegetation from the cemetery in 1983.

We passed along the information and photos to Jitka for her to add to the database. This village is representative of so many other towns like it, dotting the central European countryside. While we often associate the large cities with the sizable Jewish communities and learned chief rabbis, how many of our own great-grandparents and ancestors came from villages like Zderaz — where the Jews were often poor in knowledge and finances, but — as the shul we saw testifies — were deeply connected to their Jewish heritage?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 668)