Ulpan

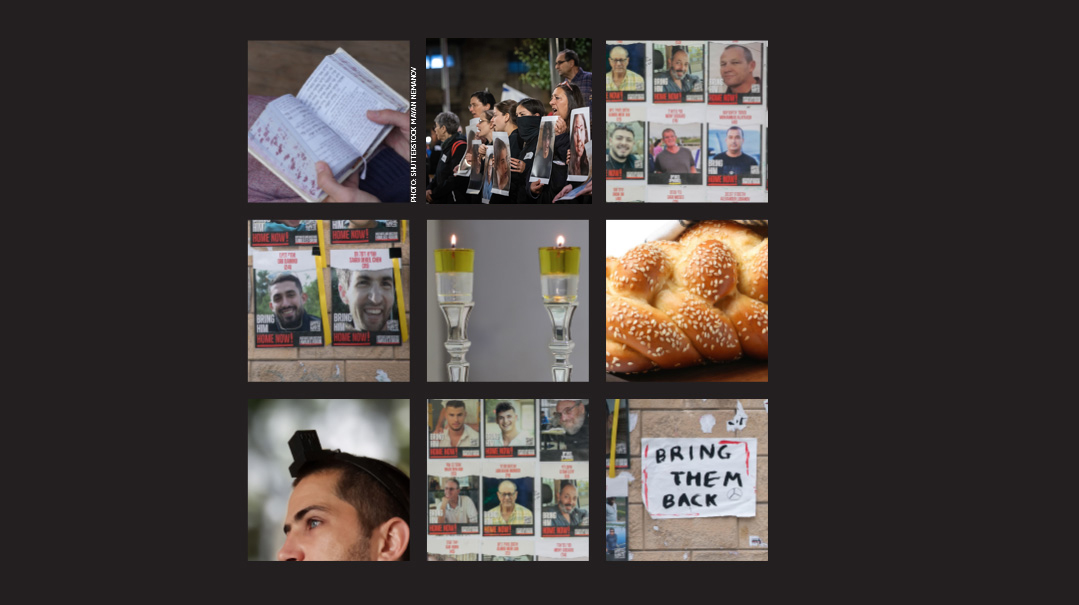

| March 12, 2024Recent months have handed Israelis a new script, and the words I’m learning have… a different flavor

I

teach English in an Israeli high school, and my students and coworkers teach me a lot of Hebrew. Recent months have handed Israelis a new script, and the words I’m learning have… a different flavor. Below, I present five words (the maximum number of new words I’ve found students can learn in one sitting), using research-based methods for vocabulary instruction: providing a definition, a synonym, an antonym, and, wherever possible, repeated exposure to the word in context.

קשוח (adjective): tough

This word is not to be confused with kishu, zucchini, which, if you’ve ever sauteed one, you’ll know is actually the opposite of kashuach.

I first encounter this word in our teachers’ room. The day before, a relative of a faculty member had fallen in Gaza, and the funeral was interrupted by an air raid siren that sent the mourners to the ground with their hands over their heads, shielding each other with their bodies.

“How was your day yesterday?” one teacher asks the other.

She leans on the counter, hunched, cupping her warm coffee, and sighs: “Yom kashuach.”

I sense that the word is something of an onomatopoeia: the long middle syllable, the “shu” that casts ripples through her cup — is her inhale, and the culminating sound — the guttural, despairing “ach”— is her exhale.

I hear in that word the strain of having a husband in miluim and a home full of young kids (whose well-being she confirmed with panicky fingers when the siren went off and she was pressed to the ground on Har Herzl).

Soon, she’ll put down her cup, smile, and go out into the hallways, but for now, in the quiet of the teachers’ room, she allows herself a sigh: kashuach.

המצב (noun): the situation

“Hamatzav” is the catchall term for the state of affairs in Israel post-October 7. Anything and everything that is not as it was is attributed to the matzav. It’s the reason the grocer gives for the inferior quality of the potatoes (the fields in the south were damaged); the reason our test schedule is canceled; the reason we write report cards with an extra ayin tovah — since many students have fathers and brothers in the army, schoolwork understandably yields to the added responsibility they shoulder at home and in their communities. It’s the reason, in the early days of the war, that I arrive at school and rub my eyes: Did the students shrink?

They didn’t; a gan whose bomb shelter is being renovated has moved into our school, which is why, walking down the halls next to towering high schoolers, there are little understudies with brightly colored tiks.

In come their set pieces: little tables and chairs, craft supplies, puppets.

During circle time, I hear a little boy monologue about his cleaner, who, as it turns out, is not Jewish but is still a good person who doesn’t want to hurt anyone. Several other kids sagely attest that they, too, have non-Jewish cleaners who are also not bad people.

This scene, this set, this theater of the absurd: the matzav.

שגרה (noun): routine

For me, shigrah evokes the faintly nauseating staleness of air under a face mask. The word was ubiquitous in Israel during Covid, as public policies (learning capsules, vaccinations, etc.) were directed toward returning us, finally, to shigrah. Now, with the word’s reemergence, the only shigrah my students expect in life is the total lack of it. One said she wouldn’t know what to do if she had a school year with the same timetable from beginning to end — would it feel too boring?

Yet that’s precisely why renditions of the show “Shigrah” are currently being staged in households, workspaces, and schools across the country: When everything is off-script, there’s comfort in reading predictable, familiar lines. On one particularly challenging day, a teacher tells me that she could barely get out of bed after hearing the news from the battlefield. But she had to get up and teach. Being in the classroom, she says, gives her back her breath.

Shigrah, then, is nothing short of oxygen. But it is also always in tension with its enemy — hamatzav. To harp on commas versus semicolons, or stress over the tests seems almost farcical when hostages stand center stage. Also, as much as we try to keep the school day an oasis of shigrah by not dwelling on the war during our lessons, the “matzav” — whether through the armed guard who now accompanies us on class trips or through the harrowing news story the students hear on the bus to school — inevitably breaks the fourth wall.

דקת דומיה (noun): moment of silence

I first hear this alliterative phrase 30 days after October 7, when our school observes a moment of silence in memory of the fallen. We gather in the hallway between classes, and the students stare at the floor and shift their weight from side to side as the curtain on our joint performance slowly descends.

We are all backstage now. Gone is our sustained, exhausting effort to maintain that crucial pretense, day in and day out, of shigrah — to play to perfection our respective roles of teacher and student. In that dakat dumiyah the masks come down, the props fall away, and we are left to face the pain.

It’s a very long minute, the length of a sigh that stretches back centuries to our High Priest accepting the loss of his two sons with dignified silence.

Then the masks come back on. Intermission’s over. The next class period is about to begin.

מאיזה חומר קורצו (phrase): from what are they carved?

I get an email that my class is being canceled because of a lecture on the topic of eisek habish. There are no students around to consult with, so I dutifully plug the words into Google Translate: “the laundry affair.” Hmm… something’s just not adding up. My class is not being canceled for a lecture about spin cycles.

I do a little more research and discover that eisek habish was a covert Israeli spy operation in Egypt in 1954. (Read up on it, but know that the story was so recently declassified that there are Israelis who will still instinctively whisper when talking about it.) At one point in the lecture, the speaker shows an old newspaper article from the 50s. The headline, marveling at the fortitude of captured Israeli spies, reads: Me’eizeh chomer kurtzu? From what supernatural, invincible material are these people carved or hewn? (Kortzanim is Hebrew for cookie/dough cutters.)

Me’eizeh chomer kurtzu is a rhetorical question, to be asked with a touch of incredulity. As in: Can you believe these amazing people? Where do they come from?

Before hamatzav, I thought I worked, traveled, and shopped with ordinary people. It’s only now, under the glare of the stage lights, that I see the true caliber of this cast and crew.

What compels a stagehand to step into the role of “The Queen,” donning the royal costume and entering the king’s inner chambers at the risk of death? To proclaim that in defense of this land and this people, if I perish, I perish — but, still, I won’t be deterred? To respond to a matzav that is kashuach in every conceivable way with the attitude of, This is my cue! — who knows whether it was just for such a time that I have been cast in this role?

It can only be because these actors are made from a material that is both of this world and beyond it; that in playing the role of the hero, they have finally shed their costumes and are actually playing themselves.

Kashuach. Hamatzav. Shigrah. The words are new, but the script is very old.

My students and I await the curtain call after its final act, when the theater will reverberate, not with dakot dumiyot, but with the sounds of orah, v’simchah, v’sasson, v’yikar.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 885)

Oops! We could not locate your form.