Twins Apart

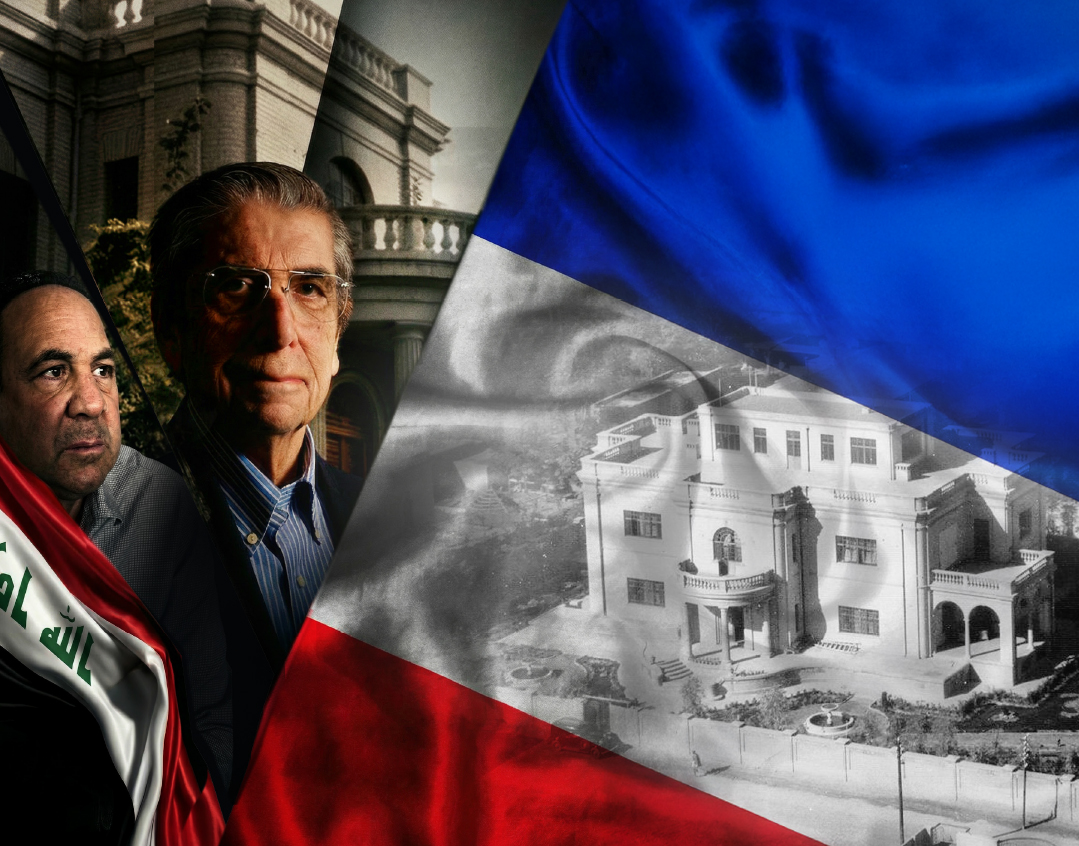

Jack Yufe and Oskar Stohr were born identical twins, yet one brother was raised as a Jew, the other a member of Hitler Youth.

I

t could have been a plot for a blockbuster film: Identical twins separated after birth — one growing up as a Nazi, the other raised as a Jew. Yet the true story of Jack Yufe and his twin brother Oskar Stohr were not just about the radically different worlds in which they grew up, but about their similarities in nature despite the incongruence in nurture.

During their first meeting, when the twins were 21, they discovered they looked alike, dressed alike, walked alike, loved the same spicy foods, and had the same hot temper, fiercely competitive nature, and various quirks.

“They were a great example of how twins, no matter where each grows up, are in fact very much alike,” Professor Nancy Segal, who studied the brothers in the 1980s as part of a 20-year research project on separated twins, told Mishpacha.

Yufe passed away November 2015 at age 82, generating a renewed interest in one of the world’s most unusual cases of separated twins.

Jack and Oskar were born in January 1933 in Port of Spain, Trinidad, to a Romanian Jewish father and a German Catholic mother. The parents split up six months later. Their mother, Leisel Stohr, returned to Germany with Oskar and a two-year-old sister during the years the Nazis rose to power. Like his fellow students, he greeted the school principal with “Heil Hitler,” and was warned by his grandmother to never let on that his father, Joseph, was Jewish. As an act of survival, Oskar joined the Hitler Youth movement like all the other young boys his age (he was just 12 when the war ended). Jack remained in Trinidad with his father, Joseph Yufe, as a British subject.

What’s in a Name

In her 2005 book, Indivisible by Two: Lives of Extraordinary Twins, Professor Segal explains that the twins’ father chose to take Jack with him because he was easier to raise; Oskar, in contrast, was a loud and frequent crier — a tiny difference that had an incalculable impact on their lives. While Jack grew up in Trinidad, far away from war and worry, Oskar grew up under the Nazi regime. While his mother worked, he was cared for by his grandmother, who was quite displeased by the fact that her grandchildren had a Jewish father. When he was eight, Oskar once heard something in school about “Juden” and asked his grandmother what the term meant. She responded by ordering him never to utter the word again.

But ignoring his Jewish roots didn’t help Oskar or his sister Sonia. Oskar was once summoned to the principal’s office at school. After Oskar saluted “Heil Hitler,” the principal asked him about the origin of his surname. “Isn’t Yufe a Jewish name?” he asked.

“No,” Oskar said, quickly improvising a response. “It’s French; it’s pronounced yu-fei.”

When Oskar was a little bit older, an officer with the Nazi registry discovered the brother and sister who were children of a Jewish father and were being raised as part of the Aryan race. Gestapo officers were dispatched to their home, and Oskar and Sonia, who had been raised and thought of themselves as devout Catholics and Germans, were taken into custody and scheduled to join a large group of Jewish children being deported to the death camps. The two children, who had been raised with a burning hatred of Jews, suddenly found themselves labeled as part of the Jewish people.

It was their grandmother who saved them, enlisting the aid of Oskar’s uncle, Max, a high-ranking Nazi party member. Max managed to pull some strings and to convince the officer in charge that the arrest of the children had been a mistake, and his niece and nephew were released.

At that point, in order to save her grandchildren, Oskar’s grandmother saw to it that the two were baptized, and changed their family name to their mother’s surname. Oskar was no longer Oskar Yufe but Oskar Stohr, the nephew of a Nazi party VIP.

Mirror Image

Oskar was five or six when he first learned that he had a twin brother somewhere in the world; Jack was eight when he was told. Neither of them grasped the full significance of that fact, but each later related that he had dreamed about his twin — dreams that bespoke a fear that the two might come to harm each other. Jack dreamed that he was a soldier fighting in Germany and stabbed his twin with a bayonet. Oskar dreamed he was a German fighter pilot who shot down his brother’s plane.

Once the war ended, correspondence between the two parents was renewed. Jack’s mother wrote to his father asking for help supporting her children in poverty-stricken postwar Germany. Jack took that responsibility upon himself and began purchasing basic items with his own money and sending them to his mother and brother.

Meanwhile, Joseph Yufe discovered that his entire family had been murdered in the death camp of Dachau. His only surviving relative, an aunt, left Germany to settle in Venezuela. Jack was sent to live with her, and the two made their way to Eretz Yisrael after the War of Independence in 1948, where Jack — who had been raised Jewish and considered himself as such — enlisted in the Israeli Navy. Meanwhile Joseph had moved to America, and once Jack completed his service, he and his aunt decided to leave Israel and join him in California, where he settled. They decided to take advantage of their trip to make a stop in Germany, where Jack would finally meet his immediate family members: his mother, his sister, and his twin brother.

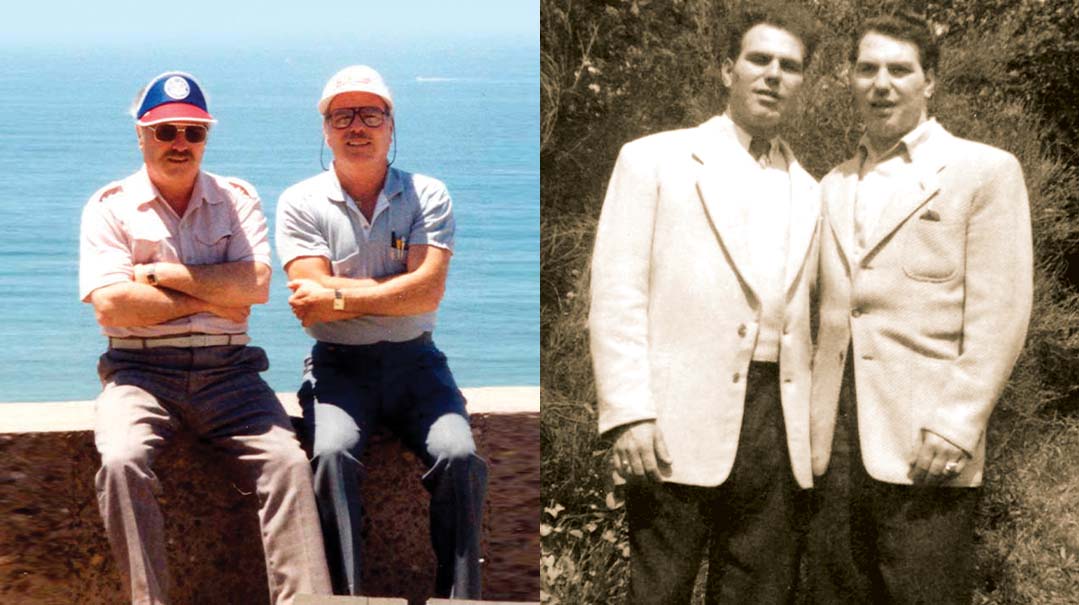

When Jack Yufe and his aunt emerged from the train, they had no trouble locating Oskar on the platform. As soon as they spotted each other, each twin had the distinct sense that he was looking at his own face — and it wasn’t a pleasant feeling. Their discomfort was intensified even further when the twins noted with surprise that they were each dressed identically.

Jack and Oskar were both wearing suits of the same color and cut, even though Oskar had bought his clothing in Germany and Jack had purchased his in Israel. “I asked Oskar, ‘Oskar, why are you wearing the same shirt and the same eyeglasses that I’m wearing?’” Jack related during the study. “And he said to me, ‘Why are you wearing the same things that I am wearing?’

“I never gave him permission to take my face, and he never gave me permission to have his. We did not enjoy being identical twins,” Jack went on, explaining the agitation both brothers experienced when they met for the first time.

Adding to the unpleasantness, Oskar hurried to remove the luggage tags from Jack’s suitcases — since they indicated that he had come from Israel. Oskar was fearful of anti-Semitic reaction and the wrath of his German stepfather, and Jack was uncomfortable with Oskar covering up his Jewish roots.

The two brothers tried hard to make the following six days, which they spent together in Germany, as comfortable as possible for each other, but there were certain things they just couldn’t overcome. Oskar feared that others would learn about his Jewish relatives; nine years after the end of the war, he was still disturbed by the fact that his father was Jewish. Both brothers quickly discovered that their most salient shared trait was a fiercely competitive nature; each of them always wanted to be the better of the two, a goal that proved to be virtually impossible for two twins who had the same genetic makeup and thought in exactly the same way. Their first meeting left the two with such onerous emotional baggage that they didn’t meet again until 25 years later.

Identity Crisis

Jack and Oskar ultimately reconnected as the result of a wide-ranging study on the behavior of identical twins.

“The study, which began back in 1979, was very important because it gave us a way to understand the interplay between heredity and the environment, and how they affect human behavior,” Professor Segal explains. “Jack was living in San Diego, and his wife heard about the study and thought it would be fitting for him and his brother to participate.” Jack contacted the University of Minnesota, where the study was taking place at the time, and asked to be included. The researchers were excited; they had never encountered such an extreme case, in which a pair of twins were separated in their infancy and raised in such diametrically opposed environments.

“There is no question that Jack and his brother had the greatest differences in background of any separated twins I have ever seen,” Thomas J. Bouchard, a psychologist at the University of Minnesota and head of the study, commented at the time. Bouchard began the study when he learned of Jim and Jim, two Ohio men reunited that year at age 39. They not only looked remarkably similar, but had also vacationed on the same Florida beach, married women with the same first name, divorced those women and married second wives who also shared the same name, smoked the same brand of cigarette, and built miniature furniture for fun. Similar in personality as well as in vocal intonation, they seemed to have been impervious to the effects of parenting, siblings, and geography. Bouchard went on to research more than 80 identical twin pairs reared apart, comparing them with identical twins reared together, fraternal twins reared together, and fraternal twins reared apart. He found that in almost every instance, the identical twins, whether reared together or reared apart, were more similar to each other than their fraternal counterparts were concerning traits like personality and, more controversially, intelligence. One unexpected finding in the Minnesota research suggested that the effect of a pair’s shared environment — say, their parents — had little bearing on personality. Genes seemed to be more influential.

“We invited Jack and Oskar to spend a week with the researchers, and we used that time to learn about every aspect of their personalities,” Nancy Segal relates. Segal, a professor at California State University, Fullerton, worked with Bouchard from 1982 to 1991. “We learned about their intelligence, their character traits, and their habits, and we found that they were strikingly similar in all three respects.”

The researchers were also quick to identify the twins’ shared penchant for competition. Some of the tests were performed separately, but whenever one of the twins discovered that his brother had outperformed him, he immediately began trying to tip the scales in his favor. The researchers also discovered that the two brothers shared many unusual habits they’d incorporated into their ordinary behavior.

They discovered, for instance, that both Jack and Oskar liked to read books in reverse, from the end to the beginning. In addition, both twins had a bad habit of frightening people and drawing attention by loud, ear-blasting sneezing. Jack also had a nervous habit of fidgeting with rubber bands and paper clips, a tendency he assumed he had picked up by imitating his father — until he met Oskar and discovered that his twin had the exact same habit. And then, of course, there was the discovery that the two made when they first laid eyes on each other: their identical taste in clothing.

“The study taught us that twins who are brought up in different environments are drawn to the same things in their respective environments,” says Professor Segal, who has continued studying twins — especially the unusual cases of twins who were separated —– to this day. “This seems to indicate that the things that interest us are based on our genes. That’s why Oskar and Jack were so similar in so many ways.

“There are two factors that affect us in life: heredity and environment. Our research has found that the genetic factor has more of an effect on behavior than we imagine. It doesn’t only influence our intelligence or our tastes; it even affects things such as how religious we will be — not in the sense of whether we will observe the mitzvos, but in terms of how involved we will be, how spiritual we will be, and so forth. The environmental factor, in contrast — such as the people we live with — doesn’t have the same effect. The level of similarity between twins who were raised separately was almost the same as the degree of similarity between twins who grew up together.”

Interestingly, Segal notes, it was clear to both Jack and Oskar that the differences that did exist between them were due to the way they were raised. “Both Jack and Oskar felt that they’d traded places — if Jack had gone with his mother and Oskar had stayed with his father, each of them would have turned out exactly like the other, and adopted ideas that were anathema to each.”

Regards from a Different World

After they were reunited by the researchers, Jack and Oskar participated in other studies, newspaper interviews, and a documentary. They continued meeting from time to time over the years, spending a number of vacations together in various parts of the world, sometimes alone and at other times in the company of their wives and children. They grew somewhat closer over the years, but their competitive natures, according to their family members, continued to create barriers between them for the remainder of their lives.

“They had an extraordinary love-hate relationship,” said Segal. “They were repelled and fascinated by each other. They couldn’t let go of the twin thing.” Oskar, who spent many years working in mines, died from lung cancer in 1997. Jack didn’t attend the funeral; he felt that the sight of his own face, which was identical to that of his deceased brother, would cause pain to Oskar’s family. At the same time, when Professor Segal continued meeting both with Jack and with Oskar’s family after Oskar’s death, the German twin’s family members told her that they planned to visit their uncle in California. When she asked why, they said, “Because he reminds us of our father.”

In 2004, when Professor Segal was working on her book, a surprise from Jack arrived in the mail: a package containing many of the twins’ personal effects and a number of photographs of the two. One of the items in the package was particularly surprising: the luggage tags that Oskar had removed from his twin brother’s suitcase exactly 50 years earlier. Oskar had held on to those tags as a valued memento, in spite of the possibility that they might evoke his stepfather’s fury. Years later, on one of his visits to San Diego, Oskar returned the tags to his brother.

The message was clear: The brothers still shared a bond, in spite of all the barriers that had arisen between them. The twins may have been separated at birth, but somehow, they remained connected in death.

Identical Yet Apart

Professor Nancy Segal was herself born with a fraternal twin sister. In fact, it was the differences between them that drew the professor to her research into the world of twins. “We grew up together but we’re very different, even though we were in the same environment,” she relates. “I was always very curious about the differences between us; I wondered how it could be that we were so different in so many ways.”

The studies she conducted dealt with sets of fraternal twins as well as identical twins. The results demonstrated that fraternal twins, who do not share identical genes, are essentially nothing more than siblings born on the same day, a fact that affects everything related to their genetic predispositions: their responses are those of brothers, not two identical people. This study, she explains, also sheds light on human behavior in general, on the nature of relationships between family members, and on the effects of environment and genetic traits on those relationships. “They are models for research and understanding of social behavior in general, and for understanding the behavior of twins in particular. This can help parents of twins, for instance, when they need to decide if they should place both siblings in the same class.”

Professor Segal believes that the generally strong ties between twins stem from their shared genetic traits. “I think that because twins have the same genes, they understand each other better.”

One special relationship enjoyed by identical twins, she notes, is with their nieces and nephews — the children of their twin. Since twins share each other’s genetic makeup, a child born to either of the twins will have a genetic connection with the other that is almost the same as his connection to his own parent. Indeed, an updated edition of Segal’s study in 2010 found that twins tend to have closer relationships with their twin sibling’s children.

That connection became particularly strong in a certain real-life case, in which two identical twin boys married a pair of identical twin girls. In that case, the children of both marriages were, from a genetic angle, essentially siblings with each other.

In addition to Indivisible by Two, Segal has authored a number of books dealing with the relationships between twins. Her book Born Together — Reared Apart, on the University of Minnesota study in which Jack and Oskar participated, won an award from the American Psychological Association. Her book Someone Else’s Twin tells the story of a case in Spain’s Canary Islands, in which one of two identical twin girls was accidentally switched at birth with another baby. Another book, Entwined Lives, is a compendium of all the information that could possibly be of use to a researcher studying twins.

To help all the parents who have encountered innumerable misguided ideas, and to address all the subjects on which there are too many preconceived notions about twins, Segal is currently working on a book on the various misconceptions that exist about twins. Another upcoming book tells the incredible story of two pairs of twins from Bogota, Colombia, who were switched at birth. Their shocking story —– of how one twin from each set was accidentally switched in the hospital, how the “twins” in each family weren’t really brothers at all, and how they came to discover their true identities — made headlines when it was uncovered last year.

Segal has spent years of fascinating research analyzing behaviors and traits of separated twins, but nothing has been quite like her most recent research on the two sets of switched Bogota twins — Jorge and Carlos and William and Wilbur, or Jorge and William and Carlos and Wilbur. ‘‘It’s an experiment within an experiment,’’ she said, not mitigating the pain and confusion of the discovery, yet comparing it to one of those Russian dolls: “Crack open one, and there would still be another, and another, and another.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 592)

Oops! We could not locate your form.