Turning a New Page

Dirshu’s Amud Yomi revolution fuses past, present, and future

By Gedalia Guttentag, Vienna

Photos: Dirshu archives

For a few hours last week in Vienna, the glories of the first Knessiah Gedolah a century ago seemed within touching distance as Dirshu celebrated the massive uptake of the Amud, heir to the Daf Yomi program that was launched within these very halls

Close your eyes amid the ornate, gold-leaf splendor of Vienna’s Sofiensaal concert hall, and a century falls away. The year is 1924, and the historic venue is preparing for Agudas Yisrael’s first Knessiah Gedolah. Inside the large auditorium, cigar smoke curls as chassidim rub shoulders with yekkes, and Hungarian delegates take their place alongside representatives from Eretz Yisrael. Outside, the occasional car passes through Vienna’s elegant streets, which are temporarily painted black and white by the masses of chareidi Jews.

One after another, Torah legends enter the hall. The Tchortkover Rebbe is princely as he arrives with his attendant. Crowds part to let through Rav Meir Dan Plotzki, author of Kli Chemdah. Next is the Sfas Emes’s son-in-law, Rav Yaakov Meir Biderman, followed by German Agudah leader Moreinu Reb Yaakov Rosenheim, in his distinctive bow tie and spitzbard.

The crowning moment comes as a diminutive figure walks in quickly with his head down. The Chofetz Chaim, destined to play a historic role in this great assembly by backing Rav Meir Shapiro’s call for the establishment of the Daf Yomi program, enters the hall and heads for the dais.

For a few hours last Monday afternoon, those near-mythical scenes — brought to life with the recent discovery of black-and-white newsreel footage of the event — seemed within touching distance.

One hundred years after the Knessiah Gedolah saw those gedolim grace the Vienna stage, their spiritual heirs — leading roshei yeshivah and poskim from across Israel and Europe — came together to mark the founding of the natural successor to the Daf Yomi.

What was meant to be a launch event for Dirshu’s new Amud Yomi program, delayed for months because of the war in Gaza, turned into a siyum of Maseches Brachos and a celebration of the stunning uptake of the new initiative. Over the last few months, more than 1,200 new chaburos with tens of thousands of members have taken off worldwide, based on the organization’s proven formula of tests enabling participants to master large areas of Shas. “The Amud has taken off like wildfire, among both balabatim and bnei Torah,” says Dirshu founder Rav Dovid Hofstedter.

“In previous generations, people used to go through masechtos and finish Shas,” Rav Chizkiyahu Mishkovsky, mashgiach of Bnei Brak’s Yeshivas Orchos Torah tells me. “But our generation needs tests and a program to motivate us to do the same thing.”

That link between the pre-war Torah world and the one that has risen from the ashes to replace it, was a theme of the two-day Dirshu tour that began in Vienna, moved on to the Chasam Sofer’s kever in Pressburg (now Bratislava), and finished in Kerestir, Hungary.

Given the worldwide sense of crisis enveloping the Jewish people amid the ongoing war in Israel, the road journey eastward across the lands of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire was as much about Tehillim as a celebration of the new Amud Yomi program; the presence of so many leading gedolim lent the tefillos the fervency of those first, post-Simchas Torah days of the war.

Two days spent in the great Dirshu convoy rolling across the heartlands of the bygone Torah world was a golden chance to hear from gedolim about the contrast of old and new, and for personal musings about the nature of today’s vibrant Torah world. Against the background of the Chasam Sofer’s “Chadash Assur Min HaTorah” — the staunch opposition to modernity and change that characterizes so much of the Torah world — the road journey illustrated the way that mesorah doesn’t mean stagnation, and that Torah requires constant innovation to reach a new generation.

“Today’s world is constantly busy,” Mirrer mashgiach Rav Binyamin Finkel told me as we were airborne enroute to Austria. “We have to channel that into busyness around Torah, with one mitzvah after another, one Torah program and then another.”

So yes, it’s easy to poke fun at our generation’s lavish tours to Kerestir and kumzitz-fueled kevarim pilgrimages. But after two days underway with groups from America, England, France, and South Africa who are part of a giant new undertaking, it’s clear that amid all the fanfare, a new reality has arisen: thousands of people – both avreichim and balabatim — are eager to know Shas and willing to put in the time to make it happen. Generation Kerestir is writing a new chapter in the Torah’s ancient story.

Inside the ornate splendor of Vienna’s Sofiensaal concert hall, the reporters of yesteryear wrote of the arrival of the Chofetz Chaim. A century on

Great Gathering

Perhaps inevitably, Vienna’s ancient Jewish history is almost totally subsumed by secularism and the Nazi era. This was the city of the 13th-century Rishon, Rav Yitzchak ben Moshe, known as the Or Zarua, who was the rebbi of the Maharam of Rothenburg. Like any self-respecting medieval Jewish community, it had its own persecution — the 1420 “Vienna Gesera” in which the city’s Jews endured expulsion, forced exile, and death in the name of Christian charity. In 1625, The Tosfos Yom Tov became Vienna’s rabbi, obtaining rights of settlement for the community in Leopoldstadt, the city district which became the capital’s Jewish hub.

But today, a Jewish tour of Vienna’s beautiful center — reconstructed after heavy World War II bombing — often focuses on the city’s famous secular intellectuals such as Sigmund Freud, or its Holocaust history. That’s perhaps natural given the proximity of the Mauthausen concentration camp, the city’s antisemitic history under the Jew-hating Mayor Karl Lueger, and in a country that until 1988 subscribed to the theory that Austria was Hitler’s first victim, not a Holocaust perpetrator.

Across the Donaukanal, an arm of the Danube River from Leopoldstadt, Marxergasse 17 is unlikely to be included on the itinerary. And yet here in this concert hall — Jewish owned until it was expropriated by the Nazis — was one of the defining events of the 20th century Jewish world.

As surviving photos and newsreels indicate, the turnout was impressive — a show of Orthodox force in a Jewish world in which secularism was in the ascendant.

“The city — decorated with many flags and signs in Hebrew, Yiddish, and German —temporarily turned Jewish,” wrote Israeli Agudah leader Rabbi Menachem Gevirtz. “Many Jews filled its streets and squares and chareidi Jews were seen everywhere in the streets discussing learning. The few shuls in the city filled day and night with the sounds of Torah study and Tefillah.”

The main conference auditorium, recall newspapers of the era, was decorated with large posters bearing the legends “Sha’alu Shelom Yerushalayim,” “Veheishiv Lev Avos Al Banim,” and “Beruchim Ha’baim.” Sitting in the front row were non-Jewish dignitaries, such as ambassadors and local politicians.

Elul of that year was singularly warm —enough so that there was a fear that in those pre-air conditioning days, the venue would be too stifling for the Knessiah to take place. But as Rabbi Yisroel Friedman, rav of the Tchortkover kloiz in Manchester says, his forebear Rav Yisroel of Tchortkov allayed the concerns with a clever play on words.

The regal scion of the Ruzhin dynasty —who along with other members of his extended family made Vienna their home as they fled from World War I, and is buried in the city — calmed the organizers’ nerves. “Kdeirah d’bei shutfe — a pot owned by two people, says the Gemara — is always lukewarm,” the Rebbe said. “So too,” he promised, “since this gathering has so many partners l’shem Shamayim, it won’t be too hot.”

Besides the temperature, other things fell into place at the First Knessiah Gedolah, which was no talking-shop. Twelve years after Agudas Yisrael came into being in 1912, the gathering was conceived as the vehicle to galvanize the Agudah as a world movement to regenerate the body of Klal Yisrael, which had been ravaged by two centuries of Haskalah, assimilation, and Jewish secularism.

As the great Agudah leader Reb Yaakov Rosenheim said in an address at Kattowitz in 1912, the Agudah had a sweeping vision. “For it is not an organization at the side of other organizations we are setting up. Our aim is rather to revive an ancient Jewish possession; it is the traditional conception of Klal Yisrael — Israel’s collective body, animated and sustained by its Torah as the organizing soul — which through our Agudas Israel we seek to realize in the midst of the civilized world.”

That Klal Yisrael mandate — baked into the fledgling organization’s DNA at birth —led directly to a focus on Torah study for the masses. One of the gathering’s main decisions was the establishment of a fund to support the Eastern European yeshivahs whose financial situation was dire in the interwar period.

Another was the Daf Yomi. Famously conceived by Rav Meir Shapiro, founder of Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, it was only through the backing of the Chofetz Chaim that the groundbreaking project gained a proper hearing.

On the opening day of the Knessiah Gedolah, which was the 3rd of Elul 1924, Rav Shapira met the aged gadol from Radin, and suggested the idea of the Daf. Struck by the program’s potential, the Chofetz Chaim agreed to get behind it.

“The Knessiah Gedolah begins at four o’ clock p.m.,” he told Rav Meir Shapira, who was decades his junior. “You wait until four-twenty p.m. to come in.”

The Daf Yomi founder did as he was told, and 20 minutes after the 83-year-old Chofetz Chaim’s own entrance, Rav Shapira entered the hall. When the Chofetz Chaim saw him arriving, he stood, at which point the thousands present also rose to their feet, craning their necks to see who it was that had caused the elderly sage to stand. That royal greeting ensured that when it was time for Rav Meir Shapira himself to speak and propose his new system, he was greeted with utter silence.

Rav Avrohom Mordechai Alter, the Gerrer Rebbe known as the Imrei Emes, was another driving force behind both the Knessiah Gedolah and the uptake of the Daf Yomi. On Rosh Hashanah, shortly after the conclusion of the week-long gathering, he announced after the end of davening on Rosh Hashanah night that the first daf of Maseches Brachos would be learned — and so the initiative caught on among the legions of Gerrer chassidim from where it spread far and wide.

A delegation of Gedolim headed the Dirshu mission

Jewish Heartbeat

It was the Chofetz Chaim himself who provided the rationale for the Agudah’s focus on Torah learning as the foremost priority for Orthodox activism. Speaking to the large crowd despite his taanis on the Knessiah Gedolah’s opening day, as so often, he conveyed his ideas through a mashal.

“Once there was a man who was sick in various parts of his body,” he said to the spellbound audience, “and when the doctor examined him, he saw that the patient’s heartbeat had suddenly stopped. Abandoning his examination of the rest of the body, the doctor immediately began to work on restarting the heart.”

The nimshal, explained the Chofetz Chaim, was to the emergency situation of the Jewish people which demanded immediate action. “We’ve gathered here today to find a cure for Klal Yisrael’s weakness,” he said. “The most urgent cure, to restore the blood flow in the veins of the Jewish people is Torah. When Torah learning is in danger, our entire existence as a people is in danger. We must save the Jewish pulse! Build the chadarim and yeshivos, allow Jewish children to be educated in the way of our fathers!” the Chofetz Chaim concluded his appeal.

Those urgings were heeded in the decades that followed. Amid a host of different community problems, organized Orthodoxy turned its collective power on supporting Torah institutions. The Vaad Hayeshivos — a body that provided crucial funds and coordination for the Lithuanian and Polish yeshivos during the interwar years — was one example.

Others were more localized efforts to build schools and Bais Yaakovs across Europe. But the spirit of the Chofetz Chaim’s prescription for the ailing corpus of the Klal underpinned all those efforts —including the Daf Yomi, which grew steadily in the postwar Torah world into the juggernaut that it is today.

The Amud Yomi program very consciously seeks to emulate its Daf predecessor, as the Vienna congress emphasized. “In Rav Meir Shapiro’s generation, people had more time for learning,” says Rosh Yeshivas Chevron Rav Dovid Cohen. “They would spend hours in the shtibel every day and the Daf Yomi was therefore an ideal limud. Today, people are much busier and need a limud with more geshmak to engage them. Even avreichim need that to enable them to sustain their goals in bekius. The Amud Yomi, which gives a person more time to cultivate a real enjoyment in learning, fulfills these needs.”

A random sampling of the Vienna convention participants showed that dynamic in action.

One attendee — a man in his 60s with no yeshivah background — had made his first siyum on a masechta after taking up the challenge of the Amud Yomi at the beginning of Berachos.

Chaim Immanuel of London, a graduate of Gateshead and Mir now in business, spoke of how the framework of obligation imposed by the Dirshu test cycle had fundamentally transformed his learning and life. Beginning with a 5:00 a.m. pre-Shacharis seder, where he goes through the daf, and then with a seder at 6:00 p.m. for chazarah, he now spends about five hours daily learning and reviewing the daf.

“I urge everyone not only to learn — whether daf or amud – but to enter the testing framework. It’s like a drug, and will change your life.”

Further afield, Rabbi Daniel Cohen-Talgum, South America director for Dirshu, gave an example of the revolution that is underway on the continent. “Several years ago, I met a frum real estate developer and philanthropist in Buenos Aires who didn’t dedicate much time to Torah. I urged him to start learning the Daf HaYomi B’Halachah, and he reluctantly agreed, but when I encouraged him to take the test, he was too embarrassed because he knew that he wouldn’t do well.

“I told him, ‘Please take it! Even if you get a low mark, it will be a catalyst for more growth in learning.’ He agreed and with time, he began to score higher and higher marks. Now he doesn’t get below a 90.

“That’s not the end of the story,” says Rabbi Cohen-Talgum. “When the Amud Yomi began a few months ago, he decided to join and is now among our highest scorers. This is from a man who told me that he was so busy he didn’t even have enough time to learn an amud of Mishnah Berurah a day! Now, he utilizes every free second of his day to learn and chazer the amud.”

But whatever the comparisons to the founding of the Daf Yomi, one key difference exists between now and a century ago: the sense of emergency is gone.

At the Knessiah Gedolah, Orthodoxy was on the defensive, seen as a thing of the past, whose very ability to pull off an event as sophisticated as the Vienna gathering surprised onlookers. It was only a sense of dire common emergency that pulled together such an array of rabbanim from such diverse backgrounds under the flag of fighting for Torah.

A century on, the frum world is robust, and Torah life is the future of Israeli, American, and European Jewry — by pure demographics alone. That has led to a world of fragmentation, of multiple groupings of gedolim, never rallying under the same flag, beyond sharing a table at Torah events such as in Vienna. It’s at once a sign of disunity, but also of strength; the crisis of old is gone, and the age-old division into shevatim has reasserted itself.

Torah Infrastructure

The story of how Dirshu founder Rav Dovid Hofstedter took his fledgling Toronto office shiur start-up to international Torah conglomerate isn’t new, but the organization’s sheer-reach and ambition simply to spread Torah learning, is worth noting anew — simply because it keeps breaking new boundaries.

Over the past quarter-century, more than 260,000 people have taken at least one bechinah in one of 16 core programs — some people, many more.

Some such as the popular Mishnah Berurah program — which operates 1,800 official shiurim — are open to all comers. So is the massive Daf Yomi program, which has brought Dirshu’s signature tests-and-stipends method to Rav Meir Shapiro’s enterprise. There’s no such thing as a free lunch at Dirshu: tests are rigorous, and there’s no attempt to help stragglers across the line.

Dirshu has another face as well: Its programs for elite lomdim are famed for their rigor. The Kinyan Shas program, created under the direction of Rav Aharon Leib Steinman, accepts 400 avreichim for a seven-year program in which they are tested cumulatively on all of Shas. Now in its fourth cycle, the program is so demanding that a mere 150 participants graduate. The entry bar for Kinyan Halacha, a program to train poskim, is also prohibitively high. But despite the caliber of the 3,000 applicants to the program, after five years, only 400 graduate. A new program is Kinyan Yerushalmi which follows Rav Chaim Kanievsky ztz”l’s system for mastering the Bavli’s counterpart.

But while impressive, the dry statistics don’t do justice to what this one organization has done. Like a spiritual version of Coca-Cola, which is both ubiquitous and a sign of an entry-level modern economy, the Dirshu logo — seen in shuls from North Miami to northern England — is a symbol that the community that hosts the chabura is part of the Torah world.

Dirshu doesn’t simply pay people to learn and be tested — it has become an indispensable part of the Torah infrastructure the world over. In the case of the yeshivah and kollel worlds, that’s all the more surprising given the resistance to any outside change. Today, though, Dirshu’s programs are considered an organic part of learning; its innovative tests and benchmark system so natural that it’s hard to remember a yeshivah world without them.

That was all pre-Amud Yomi. The launch of the new program after Succos defied even the hungry organization’s large appetites. The program launched with 600 new chaburos, and with the start of Maseches Shabbos, that had climbed to 850 official shiurim connected to Dirshu’s central system. Together with the independent chaburos that follow the cycle without official registration, the total is thought to be around 1,200, with 38,000 daily downloads of the Amud Yomi shiur.

Driving that vast uptake is, as ever, Rav Dovid Hofstedter himself. The aim, he says, is to learn with clarity and depth, and to retain the learning. And in the timing of the program’s launch, with the advent of the Gaza war, when the Jewish people need so many more merits of Torah study, he sees a message that it’s time to build.

“We’re living in a time of shlichus,” he told the Vienna convention. “Go to your kehillos, open shiurim and gather people to take tests. It’s all of our mission to build Torah.”

SPIRIT OF YOM KIPPUR At the underground tziyun in Pressburg, the Chasam Sofer’s wartime Tefillah was a reminder of where the true salvation lies

Reform Reversed

Spilling out en masse onto and Maxerstrasse in the crisp evening air — probably to the identical bemusement and irritation of their forebears a century ago — the Dirshu convoy boarded a fleet of buses for the 45-minute journey to Bratislava. Today the capital of Slovakia, the city is better-known in Jewish terms as Pressburg, seat of the Chasam Sofer and his dynasty.

Only 50 miles to the east along the Danube River, distance nevertheless matters in this part of the world. Vienna was both a fount of German culture, and the last stop of civilization before the barbaric east. Famed Austrian statesman Prince Metternich once remarked that “the Balkans begin at the Rennweg,” a Vienna thoroughfare not far from the Dirshu conference venue.

Jewish culture had another way of putting that same idea. Many Eastern European Jews who immigrated to the old Austro-Hungarian empire’s capital sought to blend in with their more assimilated local counterparts. That effort gave rise to the ironic Yiddish observation that a particular Jew was “nisht azoi Viener vi Bukovina — not so much Viennese as Bukovinian.”

Leaving Vienna, we enter landscapes straight out of a Marcus Lehmann novel. In this land of elegant palaces and Bohemian castles, it’s easy to imagine the imperiled Jewish communities and heroic shtadlanim who once existed in the shadow of the autocratic system that dominated here for hundreds of years.

As we drive east, to what were the former heartlands of the Torah world, we are unconsciously traveling the opposite direction from that taken by millions of Jews over the century leading up to the Holocaust who perceived that the light of advancement lay west. History has revealed that fascination with German culture — spearheaded by the Reform movement — to be a false messiah.

The preeminent foe of those Reformist tendencies was the Chasam Sofer, at whose kever in downtown Bratislava we arrive when the darkened city streets are already emptying.

Access to the kever today means entering an underground space effectively hollowed out inside an earth mound. The origin of the structure dates back to 1943 when Slovakia lay under Nazi control. As part of the construction of a nearby tunnel and bridge, many buildings were destroyed in the old Jewish quarter, including the city’s old shul. The construction work took place near the old Jewish cemetery and because of this most of the graves were moved to a new cemetery. Only the Chasam Sofer’s grave and 22 others of leading rabbanim were untouched. Due to the construction of the adjacent road, the area was elevated, leaving the remaining graves in an underground complex.

At the late-night tefillah held at the tziyun for the ongoing war in Israel, the effect of the dimly-lit subterranean location and the incredible gathering of gedolim was something like a mix between Tishah B’Av and Yom Kippur.

The effect was heightened by the rare employment of a tefillah prescribed by the Chasam Sofer himself for wartime. Back in 1809, Napoleon attacked the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the battle of Pressburg was fought, endangering the city’s inhabitants. As Rav Avraham Sha’ag, a talmid of the Chasam Sofer recorded, Pressburg’s rav and rosh yeshivah instructed that the community say the four Tehillim beginning with the words “Al Tashcheis.”

The concluding selichos, led to the Neilah tune by Rav Shmuel Eliezer Stern, rav of western Bnei Brak and a leading talmid of Rav Shmuel Wosner, were some of the most electrifying tefillos I’ve heard since the beginning of the war. Despite the centuries and the gulf in Jewish power separating the peril of Pressburg in 1809 and that of Gaza in 2024, it was a reminder that the key to our salvation has never changed.

Small Change

Eastward-bound the next day on the way to Kerestir, about 280 miles away in northern Hungary, the topography is flat, and the names of towns in the distance are like a shtibel map of Williamsburg, or Oberlander Jewish life. Nitra, Miskolc, Debrecen, are all a road-trip away, physical locations which have long since transcended their birthplaces as shuls, yeshivos, and chassidic communities in the new world.

Traveling across Hungary, we’re deep in Chasam Sofer territory — where the many talmidim of the great Sofer-Schreiber family held sway. Unlike its counterparts in Lithaunia, the Pressburg Yeshiva focused on producing rabbanim, and many of the hundreds of talmidim who graduated became rabbanim across Austro-Hungarian lands.

Followers of the Chasam Sofer’s dictum of “Chadash Assur Min HaTorah” — a halachic play on words which indicates opposition to any innovations in Jewish practice, and which is inscribed at the entrance to the kever complex — they were noted for their staunch battle against the encroachment of Reform, which in Hungary took the form of the Neolog movement.

“No community is the full heir to the Chasam Sofer,” says Bnei Brak’s Rav Stern, who was himself born in Budapest, and has written many works on the Chasam Sofer and his legacy. “Postwar, the Oberlanders gravitated to the litvish or chassidish worlds, but nevertheless, the Chasam Sofer changed the world. He very literally saved a large portion of Klal Yisrael from the inroads of Reform and secularism. By creating rabbanim who successfully blocked the takeover of communities in Hungary as had happened in Germany and Western Europe, he paved the way for many of the Hungarian-origin kehillahs that exist today, many of whom are defined by their rejection of modernity.”

“We have no idea why they decided in Shamayim that this should happen” Mirrer Mashgiach Rav Binyamin Finkel at the kever of Reb Shaya’leh of Kerestir

Food for Thought

Kerestir — or Bodrogkeresztúr, for Hungarian pedants — is both a small village and a big phenomenon. Once home to the tzaddik Rav Yeshaya Steiner, who was niftar in 1925, his kever lay forgotten for decades. But in recent years, the small trickle of mispallelim has turned into a mighty flood. 150,000 people now come to the grave of the man who gave all away to feed one hungry Jew and then another.

Kerestir lies deep in the rolling hills of Tokay wine country, which at this time of year means empty vines, mountain mists, and sodden fields. The village of 800 souls is primitive, but gentrifying in places where Jewish money is rolling in.

As the Dirshu delegation hikes up through the village to the tziyun — or takes one of many Merecedes vans driven by locals happy for employment — it’s apparent just how much Kerestir has been integrated into the global map of kevarim tours.

The Israeli men with the white kippahs busy barbecuing near the walled-off Beis Olam and handing out candies from a duffel bag while urging passersby to say a brachah in the zechus of the tzaddik is a scene straight out of Meron. It’s a reminder that for the Torah world, the roots of the present — the consciousness of what makes us tick — stretch back to the old world, which is never far away.

Inside Reb Yeshaya’s small tziyun is an intense scene. Mirrer mashgiach Rav Binyamin Finkel has his hands over his eyes as he urges the delegation around the kever to daven in the merit of Rav Yeshaya ben Rav Moshe, followed by fervent Tehillim, and the singing of “Tehei Ha’Sha’ah Hazos.”

And then it’s down to the village once more, where we’re welcomed at one of the two guesthouses operating in the town, which hosts anywhere from dozens to hundreds each week. Greeting us is Reb Moshe Friedlander, from Monroe in New York, whose father was from Kerestir and was descended from Reb Shaya’leh as the tzaddik was known.

Inside the guesthouse is a shul — and naturally, given the location, a meal. But perhaps the biggest surprise comes in a slightly-hallucinatory conversation with a local non-Jew who speaks a fluent Yiddish due to the influx of chassidim from around the world. The skin-headed man with a leather jacket in his 30s is one of the waiters at the Kerestir complex who has come to venerate the tzaddik.

“Ich heis Christian fun Kerestir,” he says with a smile. “Our parents and grandparents always knew about the csodarabbi,” using the Hungarian for Wonder Rabbi. “Then the Jews started to come back, and we started working for them.”

Christian’s turn to believe in the miraculous powers of “Reb Shaya ben Reb Moshe” as he says fluently, came about when his wife was diagnosed with cancer.

“She was scheduled for surgery on Monday, and a day before, I visited the tziyun, wrote a kvittel, and davened for my wife. The next day, at a pre-operative CT, the doctor saw that the growth had shrunk. ‘I don’t know how this could happen from Friday to Monday,’ he said, “but we’re not going to operate now.’

“Baruch Hashem, the growth disappeared without medication,” Christian concludes his jaw-dropping narrative before going back to his job.

Time Travel

Like the wagon driver in some chassidic tale of yore, whose job involves transcending time and space, the minivan operator taking our part of the delegation to Budapest airport that night is expected to defy the laws of nature (and of the road).

“Yoo,” says the group guide whose expertise in Hebrew and Russian allows only scant communication with the Hungarian-speaking driver, “Gaz!”

The driver gets the universal message and his foot goes down on the accelerator, leaving us bouncing up and down over the potholes of northern Hungary.

In between the jolting, it’s an opportunity to ask the Mashgiach, Rav Binyamin Finkel, about the very phenomenon we’ve just witnessed. How is it that a long-forgotten tzaddik buried in the remote fastnesses of central Europe has suddenly merited the arrival of such numbers? Surely frum wanderlust, kever tourism and marketing don’t explain the sheer randomness of it all?

“We’ve got no idea of why they decided in Shamayim that this should happen, but there’s no question that it’s wondrous. Like the success of a particular sefer, these things have Heavenly roots.”

Remote as Kerestir is from the grandeur of the Vienna concert hall and its celebration of a wildly-successful new Torah learning initiative, counterintuitively, they’re related.

Although not equal, both are manifestations of the same drive to find inspiration for the modern Torah world in the glories of the old world which were brutally snatched away from us decades ago.

From the power of a new Amud Yomi program which is enabling many people to dream of knowing Shas, to those finding a connection at a distant tzaddik’s grave, the new is definitely built on the old. Since that Elul in Vienna a century ago, we’ve come a long away, and hardly any distance at all.

Young at Heart

Sitting in the Sofiensaal auditorium beneath the balconies from which onlookers — presumably the many Jewish journalists who covered the events for the contemporary Yiddish and Hebrew press — would have gazed down on the congress participants, an item of family history comes to mind.

Doar Hayom, a secular Hebrew newspaper edited by Itamar Ben-Avi (Avi is an acronym for Itamar’s father and founder modern Hebrew Eliezer Ben Yehudah) sent a correspondent to the event, which it covered with a series of in-depth reports detailing the speeches. One feature — notably absent in today’s far-more scripted conferences — was a lively, even rancorous, debate among the delegates on hot topics of the day, such as the relationship of Agudas Yisrael to the Mizrachi religious Zionist movement. Speeches were interrupted with calls of “No peace for the wicked!” from the more zealous attendees, followed by responses from senior rabbanim that machlokes had no place in the proceedings.

In the paper’s initial report — dated the fifth of Elul — the lineup of gedolim was listed, including Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzinski, the Chofetz Chaim, Gerrer Rebbe, and others. Sandwiched in between those with rabbinic titles was one without: “Nosson Birnbaum” it read, and in parentheses, “Mattisyahu Acher.”

This was the famed baal teshuvah, Dr. Nathan Birnbaum, a Vienna native who had founded the pre-Herzlian Zionist movement, abandoned it to found a Diaspora Nationalsit movement centered around Yiddishism, and eventually returned to full Torah observance around the time of World War I. His pen-name, Mattisyahu Acher, was an ironic reference to the “Acher” or “other” of the Gemara who was a famous apikores.

The prominence that the Palestine-based newspaper gave to Birnbaum’s presence was a sign of the astonishment and fury in Zionist and secular Jewish circles that a leader of his eminence should have betrayed the cause to join the backward-looking Orthodox, those enemies of Jewish progress.

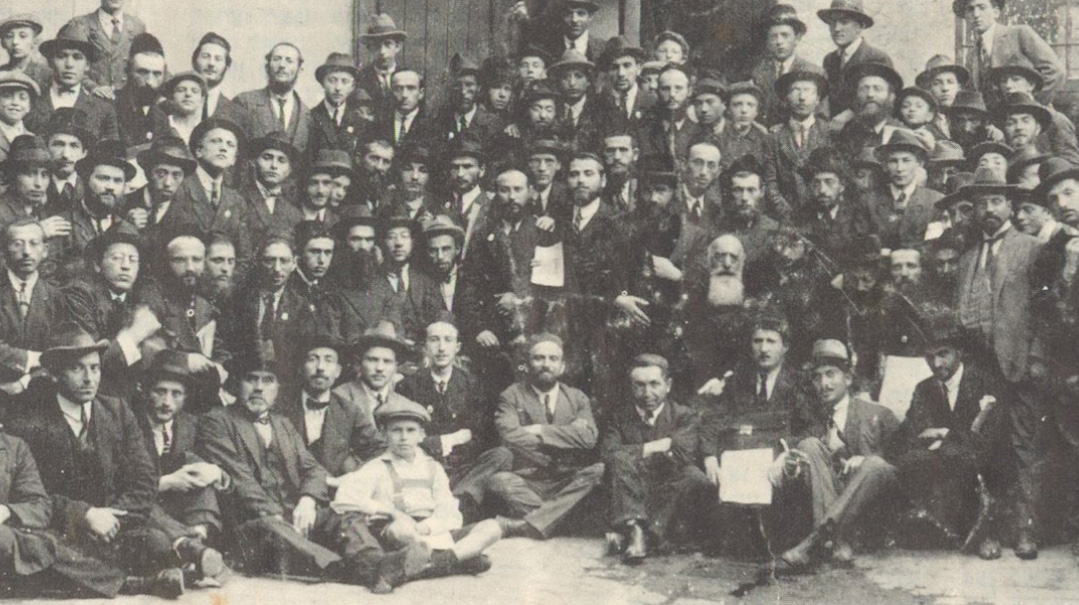

But that is indeed what happened: Nathan Birnbaum — known as der Baal Teshuvah —rose to a leading position in the newly-constituted Agudas Yisrael. His attendance at the conference is immortalized in a famous joint picture with Rav Meir Shapiro and many younger conference attendees.

The image in which it appears that the group gathered around Rav Shapiro and Dr. Birnbaum is misleading, because according to an account of the backstory, the reverse was true.

At one stage, the group posed for one of the rare group photos that took place on the margins of the conference, of which there are only a few visual tokens. Before the photographer pressed the button, a voice was heard, “Wait, let me join! I’m also young!” It was the Lublin rosh yeshivah, Rav Meir Shapiro, who indeed passed away at a young age. The camera shows him with a black beard, possibly holding the Sefer Torah which he famously carried.

Then, when the group had rearranged themselves once again around the Daf Yomi founder, there was another interruption. “I’m also young — young at heart!” came the voice.

It was Dr. Nathan Birnbaum. Then 60 years old with a majestic white beard as evidence of advancing years, his restless, youthful spirit was memorialized in a life of constant change and this photo.

HIGH HONOR Rav Hillel David, Rav Dovid Hofstedter and Rav Shlomo Eisenberger (L to R), at Dirshu’s Shabbos convention in America honoring the maggidei shiur of the new Amud Yomi program

Where Honor Lives On

By Eytan Kobre

Surprising as it may seem, what sets the experience known as a “Dirshu Shabbos” apart from other events on the frum calendar isn’t Torah. There’s a full program of shiurim and speeches chock full of divrei Torah, to be sure, but many organizations’ hotel weekends feature that, too.

Now, standing in the afterglow of a Dirshu Shabbos of Chizuk for Lomdei Torah — the seventh of its kind, held last week at Stamford’s Armon Hotel — it occurs to me that its uniqueness is not its focus on Torah, but on kavod haTorah.

In the decades since Rav Dovid Hofstedter founded this worldwide engine of Torah study, “Dirshu” has become a veritable synonym for high-intensity limud and harbatzas Torah. But in giving the gift of serious, systematic, and sustained Torah learning to tens of thousands around the globe, Dirshu has also wrought a revolution in the status of Torah learning, elevating it to a new, rarified plateau in the mind of the average frum Jew.

Dirshu has given that aspect of learning which is crucial as it is difficult — chazarah of one’s learning — a new cachet, and has turned those determined souls who learn vast amounts of Gemara and master the intricacies of halachah into an envied elite of our people, just as they ought to be. Reb Dovid has chosen to use the blessings Hashem has granted him not to emblazon his name on brick-and-mortar edifices, as others might have done, but to build instead an international palace of Torah, a royal abode for generations of lomdei Torah who are rightly regarded in their communities as princes of the realm.

Every believing Jew is raised to believe that Torah is Creation’s very purpose and that those who toil in Torah as our nation’s heroes, and their supportive wives, its heroines. But at Dirshu, these beliefs aren’t merely affirmed — they’re celebrated. Dirshu Shabbos is 48 hours of proclaiming loudly, proudly, joyously, to anyone who’ll listen, “T’nu kavod laTorah!” Not “Torah, too,” or even “Torah and…” but nohr Torah, a preeminent ideal, a value above all others.

There’s one sole reason Dirshu offers this special weekend getaway to those who take part and excel in its numerous programs of rigorous Torah study — kavod haTorah, to fete the true celebrities among us. Lots of people pay lip service to how important it is to give lomdei Torah their due recognition, but all too often the communal choices of whom to lavish with honor and acclaim send a different, conflicting message about where our real priorities lie.

Not here: Dirshu puts its money where its mouth is, sparing neither cost nor energy nor creativity and leaving no luxurious detail overlooked. The result is an experience so energizing, so uplifting that its memory lingers on through all the early mornings and late nights spent pounding bletter Gemara, the long hours spent holding down the home fort while Tatty reviews for the monthly bechinah, the missed simchahs and abbreviated vacations and all the rest of the many sacrifices large and small that Dirshu’niks and their families offer up with regularity on the altar of Torah.

Were there affluent businessmen in attendance last Shabbos? Probably. Were there lots of others who get by on a tighter budget? Most likely. But at a Dirshu Shabbos, it’s all quite irrelevant. Here, Yidden sit shoulder-to-shoulder talking not about what homes and vacations they can and can’t afford but about what they all agree they definitely can’t live without: achieving ever more ambitious goals in Torah.

Sitting together at the seudos or on the couches in the capacious lobby on Shabbos afternoon, they share with each other their personal dreams of the next Torah vista, the next mountain to conquer. Maybe it’s another go-round through Mishnah Berurah, but this time with all the Biur Halachos and Shaar Hatziyuns, or upping one’s game from covering 30 blatt Gemara a month by adding in all the Tosfos, too. Perhaps it’s to set sail on a journey of learning and testing one’s way through Yerushalmi — yes, there’s a Dirshu program for that, too.

Things happen at a Dirshu Shabbos of a kind that just don’t exist anywhere in the world outside it. Case in point: It’s a Dirshu tradition that at Minchah on Shabbos afternoon, the third aliyah is auctioned off to the highest bidder in the only currency recognized in these parts: pages of Gemara. This year, a Chassidishe yungerman named Reb Yoel Teitelbaum prevailed with a pledge to learn 7,400 blatt by this time next year. At that, an electric charge shot through the crowd, and so, moments later, so did a second one when it was announced that Reb Yoel was bestowing his treasured aliyah on the chavrusa who’d first introduced him to the amazing world of Dirshu.

There’s a genuine camaraderie that’s in the air here wherever one turns. Many of the speeches referred to “Mishpachas Dirshu,” the Dirshu family, and it’s no rhetorical exaggeration, but a palpable reality. Rabi Akiva, the Gemara (Sotah 49a) teaches, was the paragon of kavod haTorah, and perhaps that explains why during the Sefirah period his disciples suffered their grievous fate for failing to accord each other the kavod due them. The same Gemara states that when Rabi Akiva left the world, the last semblance of honor for Torah departed with him.

But at a Dirshu Shabbos, Rabi Akiva yet lives.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1001)

Oops! We could not locate your form.