Tunnel Vision

| October 5, 2021Deep in the crevices of the Kosel Tunnels adjacent to the Western Wall, we’re about to step into a time warp

Photos: Elchonon Kotler

Within the walls of the Har Habayis, the Muslim Waqf might at this very moment be working on eliminating even more traces of Jewish life amid the ancient stones and structures, as they’ve shamelessly and systematically been doing since being given authority over the Temple Mount five decades ago. Yet while they’ve been trying to change the facts above ground, determined to create a new narrative that excludes any historic ties to Judaism’s holiest site, history is indelible: The truth lies within every layer of soil. Dig down through the layers of time and you come face to face with the area’s glorious Jewish past.

There’s drilling to the left, excavating to the right, and banging above our heads, and here we are, in the deep crevices of the Kosel Tunnels adjacent to the Western Wall, about to step into a time warp. Many readers are surely familiar with the Tunnels, an underground excavation wonder that bears testimony to Jewish life during the Hasmonean and Second-Temple eras. And if you’ve been there, you’ve undoubtedly noticed some curious digging and reinforcing going on dozens of feet beneath the wooden ramps, walkways and bridges. Now we’re about to descend and find out what secrets lie so many meters deep.

Every Stone a Story

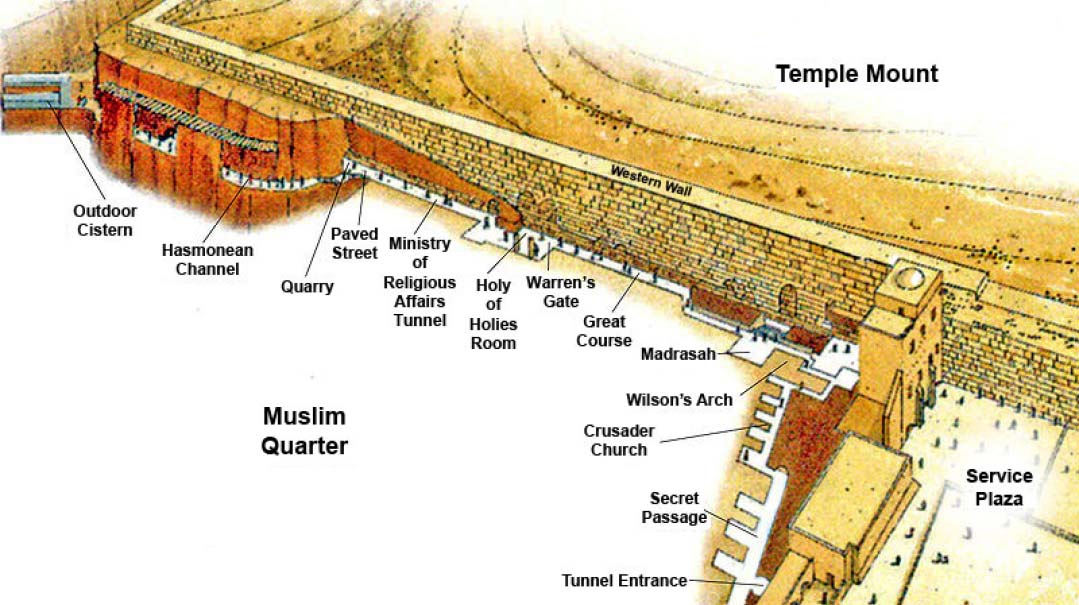

Not a week goes by without some discovery or fascinating find,” says Mordechai (Soli) Eliav, director of the Western Wall Heritage Foundation, whose organization, together with the Israel Antiquities Authority, has recently uncovered two impressive ancient buildings that abutted the Western Wall until the destruction of Jerusalem. (The original street level was at least 45 feet below where it is now, and the part of the Kosel we see today is really just the upper layer, and only 200 feet of it at that; the original Wall begins many dozens of feet below, the remaining 1,600 feet running underground, underneath what today is the Muslim Quarter. The Tunnels reveal hidden sections of the Kosel, with its mammoth stones, as it follows along underground passages, mikvaos and ancient water systems.)

The first thing Soli points to during our descent is what they call the “cliff,” a huge rock upon which one can still see the remains of an aqueduct that carried spring water to the mikvaos near the Temple Mount.

“That’s one of the main spots where the surviving Jews took shelter immediately after the destruction of the Beis Hamikdash, and from there they set out to 2,000 years of galus. So we’re standing at the Jews’ last holdout after the burning of Jerusalem,” Soli says. “You know, I’ve had the opportunity to guide some pretty distinguished people here, from all over the globe, and I always ask them one question: ‘Where else have you seen a people that for 2,000 years hasn’t given up their land, that continues believing and praying several times a day, Next year in Jerusalem?’

“When I put this question to the head of the OECD, he had an interesting answer. ‘That’s a good question,’ he told me, ‘but I have a question for you: Do you yourselves understand how this happened?’ And then it hit me — Ein ba’al haneis makir b’niso (the beneficiary of a miracle doesn’t recognize it as a miracle). We really don’t sufficiently appreciate that our very existence as a people who have survived in galus and still believe in the Geulah is completely miraculous. There’s no rational explanation for it.”

Soli steers us to a wooden staircase leading underground, so we can have a look at the findings unearthed in the recent excavations.

A quick look around reveals the extent to which every stone tells a story, every untouched layer contains the history of an entire period. Soon we feel as if we’re standing smack in the middle of ancient Jerusalem.

“Try to imagine the Ramban, who couldn’t find a minyan when he arrived in Jerusalem in the 13th century, standing on top of this place,” Soli says. “He sees the ruins and tells his few talmidim that the Geulah will yet come, and even if it’s a thousand years, a day will come when the Jews will return and tell the story of what happened here. Lo and behold, here we are, standing on the shoulders of our ancestor’s faith.”

Oops! We could not locate your form.