Triumph for the Ages

| December 20, 2022Kiel's iconic menorah returns triumphant to Germany

Photos: Elchanan Kotler

When Rebbetzin Rachel Posner took out her Kodak camera right before lighting candles on Zos Chanukah in 1931, she just had to capture the irony of the menorah in her window facing Nazi headquarters across the street. The Holocaust had not yet swept across Europe, but she knew the photograph held the secret to survival against all odds — and today, her grandson has proved her right

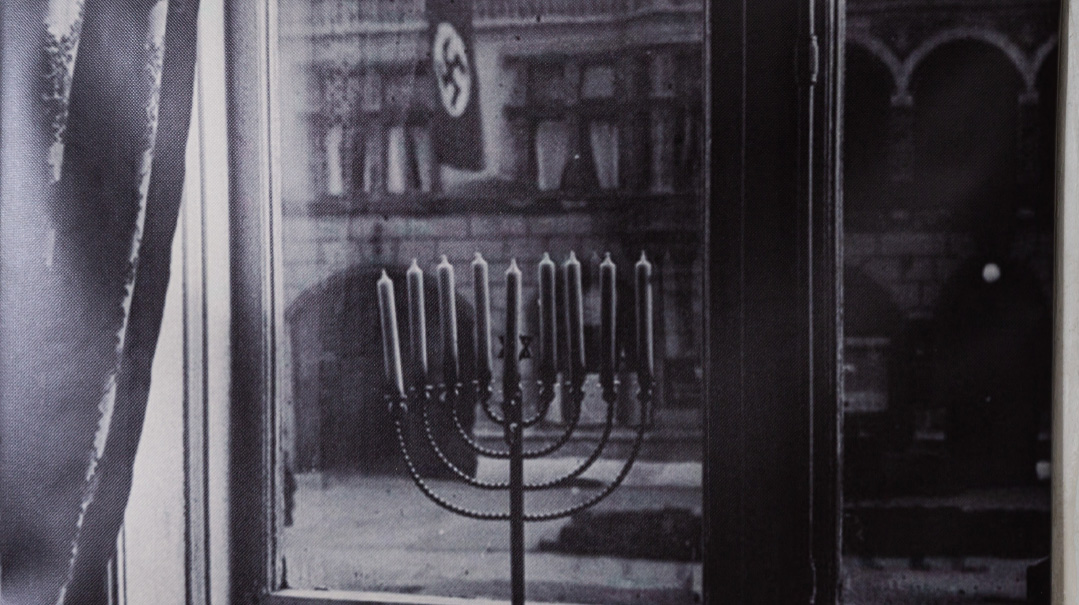

You’ve almost certainly seen the grainy black-and-white photograph.

A small, simple Chanukah menorah sits on a windowsill in Kiel, Germany. The year is 1931. Outside the window, across the street in front of the local Nazi party headquarters, hangs a banner emblazoned with a swastika.

This photo has become an iconic representation of the Chanukah message: the few, the small, against the many, the mighty. The picture is worth a thousand words. But this particular picture has words behind it: literally, in a message penned on the back of the photo, and figuratively, in the stories of the remarkable family behind it.

“Good Germans”

The backstory begins with Akiva Baruch Posner, born in 1890 near the border between Germany and Poland. The young man received semichah from Berlin’s eminent Beis Midrash l’Rabbonim and served as a chaplain in the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I. After the war, he earned a doctorate in Jewish history, and in 1924 he became the rav of Kiel, a large city in northern Germany, with a Jewish population of 500. There he met and married Rachel Wurzburg, who would go on to snap the historic photograph.

Their grandson Yehuda Mansbach has been our friend and neighbor for more than two decades, and he shared the story behind the extraordinary photograph with me.

His grandfather, Rabbi Posner, was insistent that all 500 Jews of Kiel be united as one kehillah. There was no Jewish school, so he established a Sunday program to teach the children Hebrew, Tanach, and Jewish holiday traditions.

“The whole week, the Jewish children had to deal with anti-Semitism in German schools, even before the Nazis came to power,” Yehuda explains. “But on Sundays, they could study peacefully as Jews.”

On Shabbos, the kehillah was free to enjoy Rabbi Posner’s Shabbos derashos. These were delivered in German and were so admired that occasionally even non-Jews would come to hear them.

A great compliment, to be sure, but one that became dangerous as the Nazis rose to power. Rabbi Posner was an outspoken opponent of the movement; he railed against them publicly in his derashos and wrote against them in newspapers. In a debate with a priest, he announced that Jews were good Germans, and the Nazis, who wanted to destroy the Jews, would end up destroying Germany.

Rabbi Posner’s words were prescient. Kiel was an important seaport and shipbuilding center, and late in World War II, Allied bombings nearly razed the entire city. As for the Nazis’ desire to destroy the Jews, that’s where the picture enters the story.

When Rebbetzin Posner looked out her window just before candle lighting, she knew she had to preserve the powerful message for eternity

Against the Darkness

December 1931. The final night of Chanukah, a Friday evening. Rabbi Posner hurries home to light the eight Chanukah candles before the Rebbetzin lights her Shabbos licht.

Zos Chanukah, a time where prayers have special power. Friday night candlelighting, also an eis ratzon.

Rebbetzin Posner stares at the menorah — and at the ominous swastika outside the Nazi headquarters building across the street. And looking out her window, she understands the significance of the moment. Just minutes before candlelighting, Rebbetzin Posner runs for her Kodak box camera and snaps the picture that decades later will become a defining photo of the Shoah.

It takes time to develop the photo, but when she sees it, Rebbetzin Posner immediately appreciates its stark beauty and powerful message.

On the back of the picture, in words that rhyme in German, she writes: “Chanukah 5692 (1931): Juda verrecke, die fahne spricht — Judah will perish, the flag says. Juda lebt ewig! erwidert das licht — Judah lives forever! replies the light.”

Rebbetzin Posner sends the photo to a local Jewish newspaper, where it will be printed, though without the powerful words she’d written on the back. The newspaper will soon be nationalized by the up-and-coming Nazi party, but the photo remains in their archives, where it will be found decades later.

No Future

On January 30, 1933, about a year after Rebbetzin Rachel snapped the photo, Adolf Hitler yemach shemo came to power as chancellor of Germany. The menacing rise of the Nazi party, until now a distant threat rumbling like powerful, faraway thunder, became a raging storm of anti-Semitic laws and actions.

Rabbi Posner owned a large library of Jewish books, some 500 different sets. The police, now controlled by the Nazis, burst into his home one day and confiscated five volumes, supposedly to check them for problematic content.

“Saba was a Yekkeh — he wanted his books back,” Yehuda Mansbach explains. “He wrote to the police, saying there was nothing wrong written in them, and they should be returned. And, unbelievably, one day there was a knock at the door — and there was a German policeman who came to return the books.”

Although Rabbi Posner got his books back, more worrisome developments awaited. On Saturday, April 1, 1933, the Nazis declared a boycott of Jewish-owned stores and closed all the shuls.

“Saba went to shul early on Motzaei Shabbos to daven there one last time before the shul was locked up. He and the kehillah said Tehillim 23 three times: ‘Mizmor l’David, Hashem ro’i, lo echsar — Hashem is my shepherd, I shall not lack… Gam ki eilech b’gei tzalmaves, lo ira ra, ki atah imadi — Though I walk in the Valley of Death, I will fear no evil, because You are with me.”

Yehuda adds that until today, even when he davens on Friday night in a nusach Ashkenaz shul where they don’t recite this perek of Tehillim, he always says it to himself three times in memory of that last prayer in the shul of Kiel.

That night, the shul was closed and locked. And five years later, on Kristallnacht in November 1938, the shul was torched and destroyed.

But painful as the closing of the shul was, that fateful April night in 1933 was to get even darker. A young Jewish man had taken the train to Kiel on Shabbos to visit his father. He reached his father’s store and found police there; the boycott of Jewish businesses had begun, and nobody could enter. The young man insisted he was just there to see his father, but the police stood their ground and wouldn’t let him in. He tried to push past them, so they grabbed him and took him to the police station.

And there, this young Jew, a boy who simply wanted to see his father, was shot to death.

When Rabbi Posner heard the horrific news, he ran straight to the police station. The young man wasn’t from his congregation, wasn’t from Kiel, wasn’t even shomer Shabbos — but he was a Jew, and he needed to be brought to kever Yisrael. For days, Rabbi Posner haunted the police station, pleading for permission to properly bury him.

Finally, days later, the police agreed to release the body, but with two conditions: Rabbi Posner would take the body to a distant city, accompanied by police, and the funeral would take place without anyone else there, presumably so the police could avoid the consequences of their crime.

Rabbi Posner agreed — but before he left, he called the rav of the community where the young man would be buried and asked him to bring every single Jew there to the funeral, to give a final kavod to a young man murdered simply for being a Jew.

Yehuda tells me that when Rabbi Posner left for the funeral, his wife didn’t think she would ever see her husband again, because he had so openly defied police orders. It was a miracle that Yehuda’s grandfather wasn’t detained then and there, but the community realized that it was only a matter of time before their rav’s outspoken resistance would lead to his arrest, or worse. They begged him to save himself and his family and leave while they could.

In June 1933, Rabbi Posner, Rebbetzin Posner, and their three children — including six-year-old Shulamis (Shula), Yehuda Mansbach’s mother — left Kiel, and Germany, forever.

All of Kiel’s Jewish community — 500 men and women — came to the train station to see off the Posners. There, Rabbi Posner gave his final derashah: He told his beloved congregation that the time had come for all of them to leave. There was no future for Jews in Germany. They should find their way out of the country as fast as they could. But they should always remember — they were the Jews of Kiel.

Apparently, his words entered the hearts of those listening at the train station. By the time the Nazis came to make Kiel Judenrein some years later, only a handful of Jews remained. Some of the community had gone to Palestine (many to Kibbutz Tirat Tzvi, the first religious kibbutz), some to the United States. Rabbi Posner’s final derashah helped save the lives of the congregants he had led for so many years.

The Posners spent a year in Antwerp, Belgium, where Rabbi Posner opened a small Judaica store. His siblings had made it to Palestine, and they arranged certificats for the whole family through Chief Rabbi Rav Avraham Yitzchak Kook. Settled in Eretz Yisrael, the man who had demanded — and received — his seforim back from the Nazis became the head librarian at Jerusalem’s Heichal Shlomo.

And what of the menorah that had traveled from a window ledge in Kiel to a home in Eretz Yisrael? It remained a family menorah. Rabbi Posner lit it every Chanukah in his window in the Bukharan neighborhood of Jerusalem, where they now lived, and the menorah fulfilled its mission of pirsum haneis with the family members who watched the candles dancing, and with the neighbors and passersby who admired its twinkling lights.

After Rabbi Posner’s petirah in 1962, his daughter Shula, who lived in Haifa, inherited the family menorah. When Akiva Baruch Mansbach, Shula’s grandson, was born on Simchas Torah 1984, Savta Shula said the family menorah would go to this child who bore her father’s name. The menorah moved to Beit Shemesh with the Mansbachs, where, every Chanukah, it would be part of a continuous celebration of family tradition.

But that would soon change, because the menorah’s story was destined to be shared with a much wider audience.

Yehuda Mansbach and his family members at a Yad Vashem ceremony. The museum couldn’t believe this national treasure was just a few miles away in Beit Shemesh the whole time

A National Treasure

The celebrated photo of the menorah and the Nazi banner reached Yad Vashem years before the menorah — and the story behind it. Early details are blurry, but it seems the photo that had been placed in a German archive somehow made its way to Yad Vashem. A copy was displayed there, but without the actual photo, without mention of Rebbetzin Posner’s strong, almost prophetic words, and without the menorah itself. The archivists at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem had no idea that the original picture and the menorah still existed — and that they could be found in nearby Beit Shemesh.

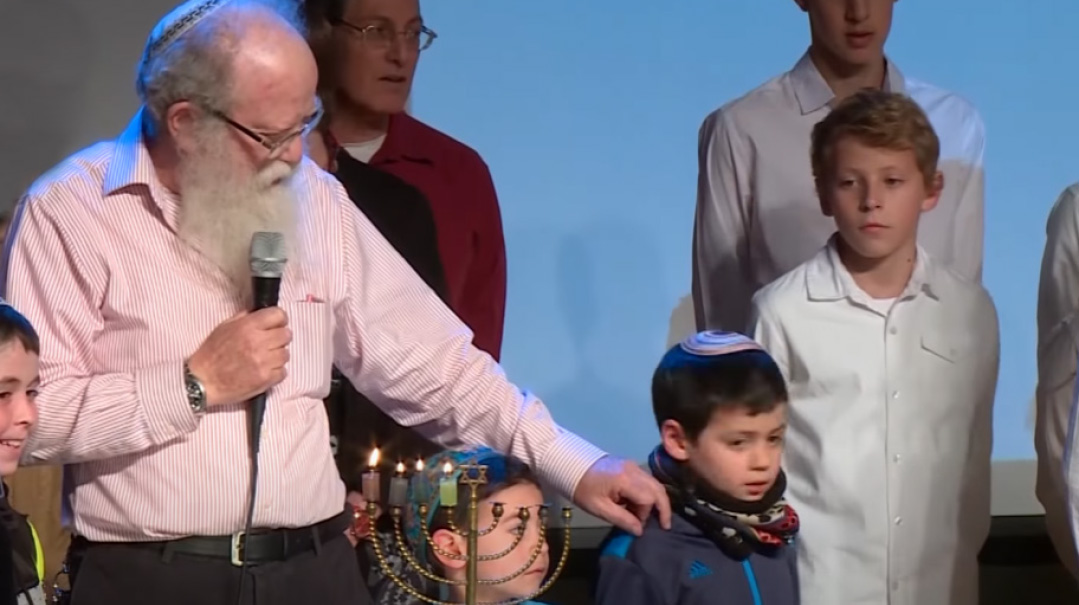

I first saw the menorah and heard its backstory about 20 years ago. We were part of a small kehillah in Beit Shemesh, davening in a miklat, a bomb shelter, while working on constructing a proper shul building. The Mansbachs had recently moved onto my block, and on Chanukah, Yehuda lit the menorah in the miklat. He shared some of his family’s story and showed us the picture.

Sometime later, an old friend, Rahel Jaskow, spent Shabbos with my family in Beit Shemesh. Somehow, the conversation over cholent and kugel turned to Chanukah menorahs. I mentioned that a neighbor of ours owned a menorah with an interesting past, and I described the photo.

Rahel’s jaw dropped. She had seen the photo once before, in a book about Chanukah, credited to a German photo archive. She remembered the photo well, and the knowledge that it had survived and could be found five doors down moved her deeply.

After Shabbos, Rahel knocked on the Mansbachs’ door. She felt a little shy, introducing herself to strangers, but her need to actually see and hold the menorah helped her overcome that bashfulness.

When she returned home, she immediately contacted the author of the book in which she’d seen the archived photo, telling him she had actually held the menorah and the original photograph in her hands. That author’s sister worked in the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., and he wrote her about the exciting find. She contacted colleagues in Yad Vashem, they got in touch with the Mansbachs, and a national treasure was born.

Actually, it wasn’t as simple as that. Of course Yad Vashem wanted to display the menorah — an important exhibit piece and teaching tool — next to the photo. The Mansbachs explained that they saw the menorah as more than that. For them, it was a devar mitzvah, part of a living legacy from their grandparents, meant to be used and not simply displayed.

Eventually, they agreed that the menorah would be given on permanent loan to Yad Vashem — but that every Chanukah, it would return home, where Akiva Baruch Mansbach would use it as his great-grandfather had, to fulfill the mitzvah of hadlakas ner Chanukah and pirsum haneis.

Going Global

Last year, in an extraordinary project, 85,000 stickers of Rebbetzin Posner’s menorah photograph were printed and distributed in newspapers throughout Germany. The organizers of the project asked readers to stick them on a window, stand in front of it, and take a selfie. Thousands of Germans sent in selfies of themselves standing in front of the menorah stuck to their windows.

This Chanukah, Yehuda Mansbach is in Germany for a few days, together with the precious menorah. The itinerary includes Kiel, as well as lighting the menorah in the Bundestag, the seat of Germany’s parliament, with some of the country’s top leaders, including German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier present.

Yehuda, who rarely leaves Israel, had mixed feelings about visiting the country that chased his family out. In Germany he has the opportunity to daven at the graves of his great-grandparents, which weren’t destroyed during the war. But he says it’s the pirsum haneis his visit is creating that makes the trip truly worthwhile.

While Yehuda is in Germany, he’s participating in another unusual tribute to the menorah. Last year, 90 years after the original photograph was taken, renowned illustrator Ali Fitzgerald created a children’s graphic novel retelling the story, based on Mansbach family pictures. This month, the short booklet, written in German, will be distributed to local schoolchildren. (The Mansbachs are also working on a Hebrew and English translation.)

And back at home, I’ll do as I do every year one night of Chanukah: Once Yehuda returns with the menorah, I’ll walk down the block to the Mansbachs’ house. Sometimes it’s just immediate family present, other years, there are children and grandchildren visiting, and sometimes, there are film crews or newspaper reporters intermingled with the family.

Everyone there will watch Akiva’leh Mansbach light the legendary menorah, a menorah with a message of eternal resonance:

“Juda verrecke, die fahne spricht — Judah will perish, the flag says. Juda lebt ewig! erwidert das licht — Judah lives forever! replies the light.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 941)

Oops! We could not locate your form.