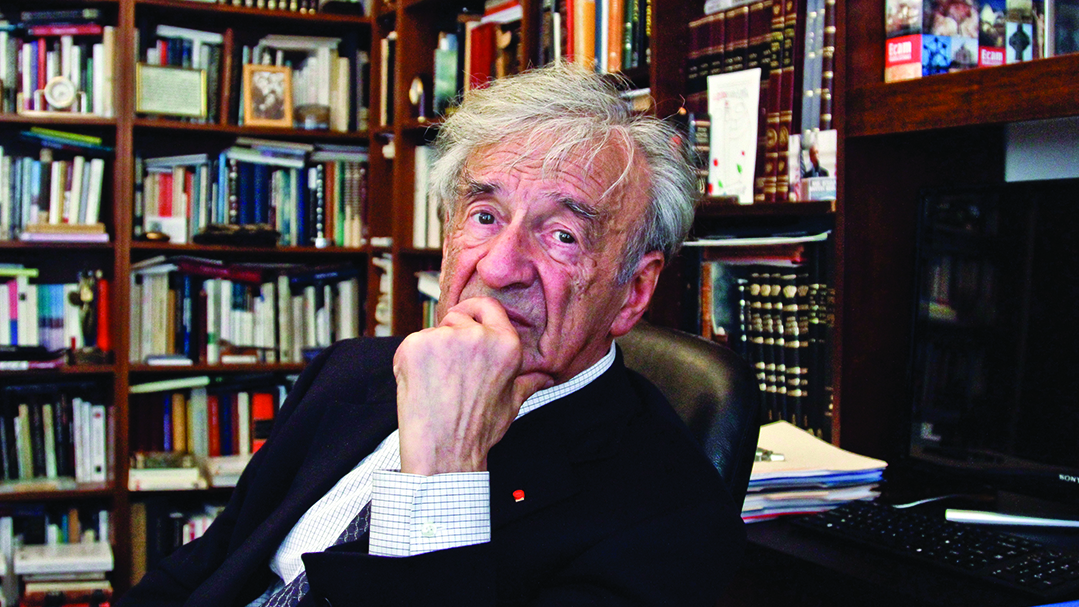

In one of the last interviews before his passing, Elie Wiesel shared his own tortured reflections.

Photo: AP

E

lie Wiesel once said: “I decided to devote my life to telling the story because I felt that having survived I owe something to the dead. And anyone who does not remember betrays them again.” Wiesel was one of the earliest and most masterful chroniclers of the concentration camp experience having experienced it himself in Auschwitz.

Using his gifts as a storyteller to publicize the horrors the world might otherwise have chosen to forget he assumed the role of a universal conscience calling the nations of the world to task against anti-Semitism and hate; assailing injustices such as the oppression of Soviet Jews South African apartheid and genocide committed in faraway lands such as Cambodia Bosnia Darfur and mostly recently Syria.

With his passing on Shabbos at age 87 accolades and condolences poured in from world leaders and opinion makers who hailed Elie Wiesel for his moral fortitude. Wiesel’s popularity was perhaps due at least in part to his willingness to admit his inability to understand extreme evil and human malevolence. During his lifetime portions of the Orthodox Jewish world had not embraced Wiesel who wrote about his personal spiritual battles stemming from confusion over the “hester panim” — Hashem’s seeming silence — in the face of the overwhelming evil he experienced. It was a topic that Wiesel alluded to in a formal but brief interview we conducted in 2014 at the sleek Madison Avenue office of the Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity.

The foundation created after Wiesel won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986 states that its mission is “to combat indifference intolerance and injustice through international dialogue and youth-focused programs that promote acceptance understanding and equality.” The foundation maintains Beit Tzipora Centers (named for Wiesel’s martyred sister Tzipora) in Ashkelon and Kiryat Malachi that help educate and integrate Ethiopian Jews into Israeli society.

The small waiting room at his Madison Avenue office was adorned with a large framed poster for a film by Elie’s wife Marion (Erster Rose) Wiesel entitled Children of the Night.

The foundation’s offices were staffed by a small cadre of bright young interns busy with paperwork and computer screens. One smiling secretary led me down a hallway lined with melancholy photos of prewar Europe and full yet tidy bookshelves into Wiesel’s spacious but equally bookshelf-laden office. He sat behind an enormous desk but rose to greet me elegantly dressed with the rosette of the French Legion of Honor adorning his suit lapel. His trademark tousled gray locks still full he invited us to the couches in the sitting area.

Having undergone serious heart surgery Wiesel had looked thin and frail. I was told in advance that he only had the strength for a 20-minute interview. His voice wasn’t strong and I often strained to catch all of his words.

His parents back in Sighet Romania were Vizhnitzer chassidim. “I had every reason to leave my religion ” Wiesel said “but I don’t want to be the last link in the chain.” Although he drifted from his roots he professed deep attachment to chassidic teachings even though his own books about great rebbes read more like storytelling and history than hagiography. He davened in the Fifth Avenue Synagogue near his home on Manhattan’s East Side but when he visited Israel as he did up to three times a year when he was well enough he enjoyed davening in a chassidic shtiebel. “When I came to the US in 1955 there was almost no chassidic world — just a few shtieblach. Today ” as he made a sweeping gesture with his arm “it’s an empire.

“Kein yirbu” he added with a sincere smile. “They are the religious edge that influences the middle.” Probing further I suggested that this flourishing of a vibrant religious community is the best revenge against the Nazis. Wiesel deflected that. “Religion, davening is not revenge ” he said.

“If there’s a line that goes through all my work,” he continued, “I think it would have to be ahavas Yisrael. The Vizhnitzer Rebbe wrote a sefer called Ahavas Yisrael. It’s a theme that is part of the chassidic movement, going all the way back to the Baal Shem Tov.”

Although Wiesel struggled with his faith during and after the war, he didn’t break the connection with Torah study. He claimed to begin every class he taught with something from the Chumash. He wrote a book on Rashi. “I love Rashi!” he declared. “Without Rashi, the Gemara could not have continued to spread in the way that it did.”

He waxed enthusiastic about the deep wisdom of our sages, their profound grasp of human nature, as exhibited by the laws of aveilus, which he termed extraordinarily sensitive and sensible, allowing the mourner to grieve yet forbidding him from unduly prolonging his grief and withdrawing from the world. “When a person is sick, he becomes the center of the world,” Wiesel said. “But as soon as he dies, his mourners become the center of the world.”

Wiesel himself was deprived of the opportunity to sit shivah for his murdered parents and sister.

His father owned a grocery store in Sighet, but considered helping other Jews to be his principal goal in life. Hungarian police once arrested and tortured him for helping Polish refugees obtain false papers.

The Wiesels were forced into the Sighet ghetto in 1944, and deported by the Germans to Auschwitz in May of that year. There the 15-year-old Elie became number A-7713. His mother and younger sister were killed, although his older sisters survived. His father, after enduring starvation, dysentery, and beatings, was sent to the crematorium just a few weeks short of liberation.

Wiesel ended up in France and Israel after the war, and became a journalist and translator for French and Israeli newspapers. When ask how he learned to write, he smiled. “In Europe, there was no such concept of learning how to be a writer,” he said. “There were no ‘creative writing’ workshops like here. You learned by doing it.”

He had nostalgia for the early days of the State of Israel, where he lived from 1949 to 1955. “When I was a journalist living in Israel, it was such a different time,” Wiesel said. “We had maybe one murder case a year to report. People were so open, so kind. On the street, they would offer water to strangers. Nobody locked their doors at night — not just in Jerusalem but all over Israel.”

Throughout his years of Jewish advocacy, Wiesel would often emphasize the Jewish connection to Jerusalem, and criticized the Obama administration for pressuring Israel to halt construction in East Jerusalem. “Jerusalem is above politics,” Wiesel once said. “It is mentioned more than 600 times in Scripture and not a single time in the Koran. It belongs to the Jewish People and is much more than a city.”

Taking on Reagan

As outspoken as Wiesel was, he built up to it slowly. It took almost ten years after World War II ended before he began speaking out about his Holocaust experiences.

Once he put pen to paper, however, the pent-up experiences poured out, first into a 900-page Yiddish memoir entitled Un di Velt Hot Geshvign (And the World Remained Silent). Encouraged by French author Francois Mauriac, he then wrote a much-abridged version in French that was translated into English as Night.

Night gained little traction for the first five years, during a time when the world still preferred to put the war behind them. But sales picked up in the late 1960s and 1970s, and it has now sold millions of copies and been translated into about 30 languages.

Wiesel came to New York on a trip in 1955 and ended up staying in the US. He wrote 59 more books since Night, and held faculty positions at Boston University and City University of New York, as well as visiting professorships at other colleges.

Wiesel’s writings exerted a strong influence on many Jewish college students, and other Jews as well, who first learned about the Holocaust through exposure to him. For those who had little or no religious background, Holocaust books, films, and museums afforded them a means of connecting to the Jewish People. But this also created a situation in which an emphasis on the Holocaust replaced Torah as the focus for their Jewish identities.

I asked Wiesel: Shouldn’t those reading about the Holocaust be encouraged to think not only about what people died for, but what they lived for as well?

Wiesel nodded. “In my experience, people get interested in the Holocaust, and then as they learn more, they become disturbed. Then they often want to get involved. But they shouldn’t stop there; they should continue to evolve.

“In every decision you make in life, think higher, and feel deeper,” he said, emphasizing his words, and then repeating them: “Think higher, and feel deeper.”

He added: “I came to that through chassidic sources.”

In 1978, President Jimmy Carter appointed Wiesel as chairman of the President’s Commission on the Holocaust. It was from that position of prominence in 1985 that Wiesel launched his diplomatic yet compelling admonishment to President Ronald Reagan for the White House decision to visit the military cemetery in Bitburg, Germany, where some 40 SS troops were buried.

Reagan had scheduled a visit to Germany on the 40th anniversary of Victory in Europe Day, where he was to meet with Chancellor Helmut Kohl, who was locked in a difficult reelection campaign. One of the campaign issues was US insistence on keeping its Pershing 2 missiles deployed in Europe for strategic deterrence against the Soviet Union, a measure that Kohl supported. It was Kohl who suggested a joint visit to Bitburg Cemetery. Reportedly, when President Reagan agreed, he and his staff were unaware of the presence of the SS graves.

Jewish leaders wielded intense pressure on Reagan to choose a different site. Matters came to a head when Elie Wiesel arrived at the White House to receive the Congressional Medal of Achievement and publicly chided Reagan during a three-minute speech at the ceremony. “Mr. President,” Wiesel said, “I implore you to do something else, to find another way, another site. That place, Mr. President, is not your place.”

Video of the event showed a slight grimace crossing Reagan’s face, although he shook Wiesel’s hand afterward and the two exchanged greetings. Reagan did lay a wreath at Bitburg, although he curtailed his planned 20-minute visit to four minutes, mainly shaking hands with German military men. Reagan did not speak there and instead delivered an eight-minute address later that same day at the site of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

No Figuring Out Hate

While Reagan found a way to climb down from the tree, Wiesel never stopped speaking up for what he believed in.

A year after the Bitburg controversy, in 1986, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Norwegian Nobel Committee described Wiesel as “one of the most important spiritual leaders and guides in an age when violence, repression, and racism continue to characterize the world.”

In his acceptance speech, Wiesel said: “Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. Sometimes we must interfere.”

In his later years, Wiesel warned the world against Iran’s nuclear ambitions, spoke out against the ongoing massacres in Syria’s civil war, and condemned Hamas for their use of children as human shields during Operation Protective Edge. He refused to subscribe to the liberal-democratic theory that if we could only remove the sources of human misery, we could eradicate hatred.

“Happiness is not a factor in hatred,” Wiesel said. “The anti-Semite is very happy being an anti-Semite.”

An alienated 17-year-old who takes a gun or knife and kills innocent people is not a classic example of hatred, he said. Instead it’s the kind of senseless killing we can’t hope to explain. Wiesel argued that he was never interested in probing the psychology of the hater.

“I know all the arguments,” he said. “But in the end, it’s a waste of time. No one can convince a hater not to hate. If people ask me, ‘So why do people hate?’ I answer, ‘Ask the hater. Why should I do the work of figuring it out? Why should I go and ask him? Why should I even have to deal with a person like that?’ ”

As far as anti-Semitism is concerned, to Wiesel, it’s merely the oldest form of hatred. “That’s because we Jews survived the longest. They look at us, and subconsciously, they’re bothered. They think: What are you Jews still doing here? We did everything we could to get rid of you! Am Yisrael has defied all the logical and mathematical possibilities for survival.”

Wiesel is survived by his wife, Marion, to whom he was married for 47 years; a son, Shlomo Elisha, named for his father; a stepdaughter, Jennifer Rose, and two grandchildren.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 617)